Guests

- Stephanie Woodardaward-winning journalist who covers human rights and culture with an emphasis on Native Americans.

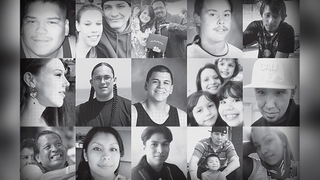

Amid a report of another police killing of a Native American woman, we continue our interview with reporter Stephanie Woodard, author of the investigation, “The Police Killings No One Is Talking About,” which reveals that compared to their percentage of the U.S. population, Native Americans were more likely to be killed by police than any other group, including African Americans.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we bring you Part 2 of our look at this massive investigation by In These Times magazine that looks at—well, it’s called “The Police Killings No One Is Talking About.” The special investigation is done by journalist Stephanie Woodard. What inspired you to do this, Stephanie?

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Well, I had been reporting—I have been reporting in Indian country for quite a while, probably 16 or 17 years. And I had certainly heard about incidences of police brutality throughout the years, and they had informed other pieces, but I had never really gotten to dig into that as an issue. And In These Times was very much interested in doing that. So, we moved ahead.

And, you know, one thing I wanted to do was go back to the question that you had about the power of tribe in all of this, because one thing that I found when I visited the Puyallups—you may also have seen on the Dakota Access pipeline, in the camp there, the people who are opposing the pipeline—and that is that tribes—I think, for many mainstream people, tribes are little groups of people somewhere—they’re not really sure exactly where, they’re not sure who they are, they’re probably different in some way, and so on. They’re sort of a mystery. And that may be part of why the mainstream media, the legacy media, doesn’t cover them very much. However, tribes themselves see themselves as big umbrellas, as stewards. I mean, certainly, the Standing Rock Sioux and their supporters, they don’t want that pipeline because it will—it will jeopardize their water, but they’re also thinking about the tens of millions of people downstream, and they’re thinking about the Earth and climate justice and bigger issues, as well.

And when I got out to Tacoma and met the Puyallup people, their name for themselves in their old language is “the welcoming and generous people.” And their family meetings that they started having on a regular basis after Jackie was killed—and a lot of it had to do with the shock and trying to figure out their grief and how do they come to grips with this—gradually those started to attract other people who had been through the same thing in their regions—some other tribal members, African Americans, Latinos, labor organizers, who—there’s certainly a long and violent history of labor organizing in Tacoma, like along the waterfront and so on. And so, a lot of people were coming to these meetings. And at the one that I attended, it was a—you know, it was the rainbow of people. And they—what they did was they set up a traditional talking circle, and everyone went around and told their story and said what was on their minds and where they were at. And there was a lot of mutual support. And a number of the women said to me afterward that they felt like they were safe on the reservation, that they had a place where they could just say what was on their mind. And then, afterwards, everyone broke bread together. As a matter of fact, Jim, that morning, the photographer, and I had been out on the crab boat, where he had set the traps for the crabs for that night’s meal. And so, they were fed a meal that included traditional Puyallup foods fresh from the sea. And so that there is a sense of tribes thinking of themselves as, as I said, big umbrellas that can bring a lot of people along. And that’s one of the first things that Jim said to me, is that when the tribe—not just the individual tribal members who were interested, but the tribe as a government—got involved, he said, “We realized that we could bring a lot of people along with us.” And in a fairly recent and good development, one of their tribal councilmembers has been named to a state task force on police brutality and, you know, having—

AMY GOODMAN: In Washington state.

STEPHANIE WOODARD: In Washington, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, we’re talking about the January 28th police killing—

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —of Jackie Salyers in Tacoma.

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Of Jackie Salyers, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And people can go to democracynow.org to see the full discussion along with her uncle, James Rideout. I wanted to ask you about another case, and it’s the case of Jeanetta Riley, this in Sandpoint, Idaho.

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: What happened to her in 2014?

STEPHANIE WOODARD: She was a young woman, early thirties. She was homeless and pregnant and distraught. And she had been threatening suicide that day. Her husband drove her in their van to a nearby hospital, where he thought he could get help. He went in. He talked to the desk. They put the hospital on lockdown. They called the police. Police showed up very quickly and got out of their cars. Within a minute of the time they arrived and within 15 seconds of them exiting their cars, she had been shot dead.

And it was—it was something that you see over and over again in terms of people who are undergoing a mental health crisis. And this is something that mental health advocates have pointed out, that approximately 25 percent nationwide of the people who are shot by police are having some kind of mental health episode—they’re threatening suicide, they’re off their meds, they’re acting out in some fashion. Family or friends calls for help. They may even specify that this is a mental health crisis. And, unluckily, in many cases, officers show up—a lot of officers. They jump out of their cars. They shout, as they did to Jeanetta. A lot of conflicting instructions. She had a knife in her hand, a small knife, with which she was threatening suicide. “Drop the knife,” “Walk toward us,” “Show us your hands,” “Do this and that,” they’re all shouting, through them. And then they shot her.

AMY GOODMAN: So, wait a second. They kill her—

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —so that she doesn’t kill herself?

STEPHANIE WOODARD: No. In the investigation that follows these kinds of incidents, usually what the police say is that they kill the person so that the person does not kill them. They usually stress how frightened they are of the person in that particular situation. Jeanetta’s—some attorneys for Jeanetta’s children pointed out that she weighed about a hundred pounds, she was five feet tall. They closed in on her. She did not rush toward them. And so, they, in essence, created a situation that they felt they needed to shoot their way out of. And that—I talked to someone who was a beat cop and then a homicide detective in Washington, D.C., and now he is a consultant on a variety of criminal justice matters. His name is Jim Trainum. And he said that police are generally trained to rush into a situation, and then they may often feel, having rushed in, that the only thing they can do is shoot their way out of it.

And there are, on the horizon, some interesting new models that may start to chip away at that. One is called crisis intervention training, where police are literally trained to slow down, take cover, assess the situation, secure the scene, get the help of a mental health professional. Another one pairs police with mental health professionals right from the get-go, so they leave together. And then, the goal is not to kill the person, but to get them someplace where they can be evaluated.

AMY GOODMAN: You begin your article: “Suquamish tribe descendant Jeanetta Riley, a 34-year-old mother of four, lay facedown on a Sandpoint, Idaho, street. One minute earlier, three police officers had arrived, summoned by staff”—

STEPHANIE WOODARD: At the hospital where her husband had taken her, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And here you had Riley—homeless, pregnant, history of mental illness—threatening suicide. She had a knife in her right hand and was sitting in the couple’s parked car. Her partner had gone inside.

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Right. And then, at a certain point—

AMY GOODMAN: To help—to the hospital, to get help for her.

STEPHANIE WOODARD: To the hospital, yeah. And then, at a certain point in all of this, she did get out of the car. Yeah, OK.

AMY GOODMAN: “Wearing body armor and armed with an assault rifle”—

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —”and Glock pistols,”—

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —”the officers quickly closed in on Riley—”

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —”one moving down the sidewalk toward the van, the other two crossing the roadway. They shouted instructions [at] her—to walk toward them, show them her hands. Cursing them, she refused.

“’Drop the knife!’ they yelled …

“They pumped two shots into her chest and another into her back as she fell to the pavement. Fifteen seconds had elapsed from the time they exited their vehicles.”

STEPHANIE WOODARD: The speed of the interaction is very common in a lot of these interactions, whether they are mental health crisis-related or there’s some other issue involved. And mental health professionals, Bonnie Duran, for example, a University of Washington professor I talked to in the story, you know, obviously, say there has to be another way. In terms of the scientific research on whether crisis intervention training for the officers or pairing the officers with a professional is the better way to go, we still don’t really know yet. But there does seem to be some improvement possible. What she said was that, really, what we should do is be—is invest more in social services that mean that these—the people who are in those situations never get into those situations, that there’s help before a police officer has to be sent to deal with it.

AMY GOODMAN: And as we wrap up, Stephanie, what were you most surprised by in this investigation?

STEPHANIE WOODARD: Well, I think the mental health piece was a big surprise, the jeopardy that anyone with any kind of mental health problem is in in an encounter with police. In a difficult situation like that, where it is all happening in seconds, it is extremely difficult for an individual who obviously has never been in that situation before, isn’t trained, to figure out how to respond—what will keep them safe, what will keep them alive. And they may just simply make a mistake.

And then, the other thing, I think, was a positive thing, and that is the power of a tribe to effect positive change and to bring other people along with them who come to them for—for shelter in very difficult times. And that was very moving, and I thought it was a very powerful thing that the Puyallups are doing, along with their initiative, which is a very practical thing—to change the law.

AMY GOODMAN: Stephanie Woodard, I want to thank you for being with us, award-winning journalist who covers human rights and culture, with an emphasis on Native Americans. Her recent article, a special investigation for in In These Times, “The Police Killings No One Is Talking About.” And we’ll link to that.

Also, you can go to democracynow.org for Part 1 of our conversation on this chilling subject. This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman.

Media Options