Topics

Guests

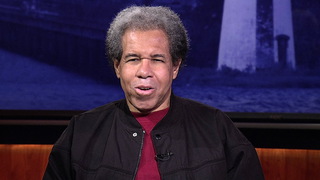

- Albert Woodfoxlongest-standing solitary confinement prisoner in the United States. He was held in isolation in a six-by-nine-foot cell almost continuously for 43 years. On Friday, Woodfox was released from a Louisiana jail. He is a member of the Angola 3.

- Robert Kingmember of the Angola 3 who spent 29 years in solitary confinement for a murder he did not commit. He was released in 2001 after his conviction was overturned. He’s written a book about his experience, From the Bottom of the Heap: The Autobiography of Black Panther Robert Hillary King.

- Billy Sothernone of the trial attorneys representing Albert Woodfox, one of the Angola 3, who was released from prison on Friday. He is the author of Down in New Orleans: Reflections from a Drowned City.

- Michael Mablebrother of Albert Woodfox.

Extended interview with Albert Woodfox. On Friday, he was released after more than 43 years in solitary confinement. The former Black Panther spent more time in solitary confinement than anyone in the United States, much of it in a six-by-nine cell for 23 hours each day. In his first broadcast interview, Woodfox is joined by his brother, Michael Mable, former imprisoned Black Panther Robert King and attorney Billy Sothern.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Renée Feltz. And we’re bringing you a Democracy Now! exclusive.

Albert Woodfox walked out of prison on Friday, on February 19th, on his birthday, after spending more than 43 years in solitary confinement—more than anyone else in U.S. history. He walked out of a jail in Louisiana. This, after he entered a plea of no contest to charges of manslaughter and aggravated burglary of prison guard more than four decades ago—a crime he to this day maintains he did not commit. Prior to Friday’s settlement, his conviction had been overturned three times.

Albert Woodfox and the late fellow Angola 3 member Herman Wallace were accused in 1972 of stabbing prison guard Brent Miller. They have always maintained their innocence, saying they were targeted because of their attempts to address horrific conditions in the Angola prison in Louisiana by organizing a chapter of the Black Panther Party. Herman Wallace was freed in 2013, days before he died of cancer.

Albert Woodfox with us from the public television station WLAE in New Orleans in his first broadcast interview. Also with us from that studio is Robert King, the other surviving member of the Angola 3. He served 29 years in solitary confinement. And Albert Woodfox’s attorney is also with us from New Orleans, Billy Sothern.

Albert Woodfox, can you talk about your plans today? You’ve walked out of the prison. You haven’t been free in 45 years. What are you most struck by? What are your greatest challenges now or your moments of joy since Friday?

ALBERT WOODFOX: For me, you know, as strange as it may sound, when I was in prison, I had established who I was and ways to fight for what I believed in. Being released into society, I am having to learn different techniques, you know, of how to—I’m just trying to learn how to be free. I’ve been locked up so long in a prison within a prison. So, for me, it’s just about learning how to live as a free person and just take my time. Right now the world is just speeding so fast for me, and I have to find a way to just slow it down and, you know, just enjoy my family. That’s been a great source of energy. Being able to sit down with King and laugh and touch him, and he touch me, and hug each other and stuff is, you know, grateful. He has been a man that ever since he walked out of prison, he has spent the last 15 or more years of his life fighting for—to get me and Herman out. And, you know, there are very few human beings who have shown the character and the strength and the determination as my friend and comrade, Robert King.

AMY GOODMAN: Robert King, you met Albert Woodfox in prison, is that right?

ROBERT KING: I did. I met Albert Woodfox for the first time, yes, in prison. And yeah, I met Albert in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Your forming a chapter of the Black Panther Party in prison, what that meant, what year it was, and the reaction of the prisoners and also the institution?

ROBERT KING: Well, it was—you know, just to put it in context, Amy, Albert and Herman, they preceded me into prison, and they went into the main prison population, and it was there that they began to establish, you know, some of the teaching of resistance, and doing it peacefully, peaceful protest. Of course, they was met with, you know, anything but peace. So, it was Herman, Albert and other sympathizers and empathizers of the Black Panther Party movement that—you know, that got together and began to struggle against this. I was still being held in the New Orleans Parish Prison at the time. And so, it was as a result of their initial efforts that begun all of this.

And some months later, after I was sent to Angola, after all of this had happened, including the death of Mr. Miller, they, you know, knew I was affiliated or I was a part of the Black Panther movement, a protest movement or whatever you want to call it. Anybody protesting was a Black Panther at that time anyway. And they decided that they would send a record along with me that I was an instigator, an agitator and a troublemaker. And so, that was their reasoning for locking me up. However, they had to do it in a legal manner. They placed me under investigation, and they investigated me for the entire 29 years that they held me in prison in solitary confinement. They were—but, Amy, we have—

AMY GOODMAN: Investigated you for what?

ROBERT KING: The murder of Brent Miller, even though I was 150 miles away, I had never met the man in my life, I didn’t know him. And I was under investigation. And I was—

AMY GOODMAN: But they knew where you were. You were in prison, in another prison.

ROBERT KING: Of course they knew where I was. They knew where I was, but this is the—you know, this is the legal system. A lot of time, a prisoner is convicted on conjecture, by implication. And this is what happened to me. They had me—if I hadn’t been in prison, believe me, at the time Mr. Miller was murdered, I would probably not have gotten out from—they would have charged me with this crime. But when I came back, when I came—when they did send me to prison, I saw what was going on, Amy, and what I did was I joined—you know, I joined not so much as—of course, I had become an alleged member of the Black Panther Party, but by this time I had joined the movement, I had joined the struggle. And so, it was incumbent upon me to struggle along with Herman and Albert, because they placed me in the same environment in which they had pluck Herman and Albert out of population and put them in. So they placed me in that same environment. And I knew Albert. I had met Albert, like I say, in prison. And I knew Herman, met him also in prison. And we had somehow incorporated the same philosophy. We believed that the things that were happening in prison was unjust, and we wanted to try to end that, put a stop to it. And again, it was incumbent upon me to join with Herman and Albert to try to prevent this.

RENÉE FELTZ: And, King, it’s incredible to have you both here together. I wanted to ask you and Albert to elaborate a little bit more about the conditions that you were organizing against as a Black Panther chapter. For example, we’ve heard about systematic rape of prisoners there that the guards allowed to happen. And we might also point out that the situation seemed extremely dangerous for the guards, as well. I mean, Miller was stabbed there.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, for me, as Robert said, you know, he had been transferred to Angola. And when Herman and I was in population—you know, the saddest thing in the world is to see a human spirit crushed. And that’s basically what happened with these young kids that was coming to Angola. And we decided that if we truly believed in what we were trying to do, then it was worth taking whatever measures necessary to try to stop this. So we formed anti-gang squads. And every day, when they would bring these young kids down, we would go and we would offer them friendship and protection. And for a while there, we were able to stop the sexual slave trade that was going on in Angola at the time. And as you said earlier, a lot of the security people there were profiting from this.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert, can you describe how other men who were being held in solitary responded? Who was crushed, and who managed to maintain some sense of themselves? I mean, how you did this for 43 years, I’m sure people watching around the world cannot fathom right now. But what was it inside you that enabled you to keep yourself together? And were you able to keep yourself together through these 43 years? Did you have breaks?

ALBERT WOODFOX: You know, a lot of people have asked me how. I wish—you know, the only thing I can say is I inherited some pretty great traits from my mom. And a lot of things that she tried to teach me when I was a young teenager, you know, didn’t make sense, and all of a sudden it started to make sense.

And, you know, we’re talking about a 40-year period. You know, I went through claustrophobic, which I still suffer from at times, panic attacks. You know, we’ve been through physical attacks by security. But somehow, I always found the strength to continue. One of my inspirations was Mr. Nelson Mandela. You know, I learned from him that if a cause was noble, you could carry the weight of the world on your shoulder. Both King, I and Herman thought that standing up for the weak, protecting people who couldn’t protect themselves, was a noble cause.

You know, we—I mean, there were some horrendous conditions. Food and other things that were meant for the inmate population were being taken by security people. And, you know, if you wanted to get some tool or something, or raincoat or something, to go work in the field, you had to buy it or enter into some alliance or whatever to get the tools that were meant for you. And so, you know, it was a lot of things to struggle about, and that’s what we did.

Angola was segregated at the time, and we worked hard to try to bridge—build a bridge with the white inmates, because, you know, the divide-and-conquer philosophy was a part of the prison. And, you know, it’s kind of hard to put something that’s inside of you into words where everybody can understand. But that’s basically what happened. You know, we just knew that someone had to be strong enough and willing to sacrifice everything to stop some of these horrible things that were going on in Angola.

RENÉE FELTZ: Indeed, Albert, you’ve described yourself making a conscious decision that you would never become institutionalized. And you said that was key to helping you maintain your sanity. You’ve said in some interviews that you remained concerned about what was going on in society, and you knew that you would never give up and promised yourself that you would not let them break you, not let you—drive you insane. And I wanted to ask about the state’s characterization of how you were held. They’ve disputed that the conditions were solitary confinement. I wanted you to respond to that point that the state is arguing.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, you know, I can’t make sense. You know, the evaluation process by classification in mental health and all that, I got the highest marks you can get for it. It was determined that I was not a predator. It was determined by independent people at the prison. But yet, Warden Cain and some of his security staff just didn’t know it, you know, and they continued to call me and Herman, who was locked in a nine-by-10 or nine-by-six cell, the most dangerous men in the world, you know? We went for years and years and years without any disciplinary reports and stuff. None of that seemed to matter.

You know, institutionalized is when guys become concerned with the prison and what’s going on and contribute to the prison cause. You know, for us, the object was not just to survive, but to continue to grow and improve ourselves as human beings. When you become institutionalized and look inward, you pretty much give up on being a part of society. And we knew that our own humanity depended upon us not losing our right to be a part of society, even though we were in prison. And that, you know, it gave us strength. You know, we were not fighting for the prison, but we were fighting for society, we were fighting for all of the injustices that happened in America and around the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Billy Sothern, I wanted to ask you about getting justice in Louisiana, where you’ve practiced law for many years—Louisiana, the heart of the world’s prison capital, where more people are behind bars than any other state per capita, an incarceration rate 13 times that of China. Louisiana also ranks among the highest in the country in terms of the number of people per capita who are exonerated after serving years in prison for crimes they did not commit. Can you talk about getting a fair trial in Louisiana and why you feel it’s so difficult?

BILLY SOTHERN: Well, I think if we look at Albert’s case, obviously, we see many things about Albert and the case that are so exceptional. But a lot of the things about Albert’s case that led to his wrongful conviction are actually representative of this totally dysfunctional system. If you look back through the course of Albert’s case, we see the suppression of evidence by the prosecution. We see ineffective assistance of counsel for people who can’t afford their own lawyers. We see an appellate process that’s incredibly resistant to providing new trials, even when it’s the manifest and right thing to do. So, while of course it’s amazing that after 43 years Albert Woodfox is now out of prison, it’s also horrifying that it took 43 years for this injustice to be corrected.

And, you know, when we look at the pretrial situation that we were just in, the question we need to ask ourselves is: You know, can we trust a jury to get—to reach the right result in this case? And I think, problematically, the answer to that question is not a clear yes. You know, we’re left with a situation where we could never be quite confident that we had everything that we needed to have. We’re left in a situation where 43 years after the fact, we have to investigate a case that was never properly investigated. And, you know, we’re left with a jury in a parish where Albert couldn’t have gotten a fair trial. So, I think, again, if we look at some of those things, we see the—we see writ large the crisis of indigent defense in Louisiana and criminal defense in Louisiana, where there just is a greatly unequal playing field, unequal resources. And if we look what’s going on in Louisiana right now, there’s this incredible crisis with funding for indigent defense, where prisoners who—inmates and criminal defendants who face charges just as serious as the one in this case, are not being afforded the right to counsel that the Constitution provides, but in fact are provided with sometimes very well-meaning and well-intentioned lawyers who are thoroughly overburdened, who have no access to investigation and who can’t meaningfully create balance in what’s supposed to be an adversarial process.

So, those are many of the same things that we see in Albert’s case. And when we look at the case, even though so much of what happened happened so long ago—1973, 1998—can we be confident that those things are not happening in Louisiana today? Absolutely not. Many of the same things that led to Albert’s wrongful convictions in those two instances are persistent features of the criminal justice system in Louisiana.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what it meant to have a new attorney general in Louisiana, the fact that Buddy Caldwell was defeated and that Jeff Landry was elected, what it meant to open that door to a settlement? And is there a financial settlement connected with this, Billy Sothern?

BILLY SOTHERN: There is no financial settlement connected to the resolution of the criminal case. The civil case is ongoing, and I hope that the same spirit of resolution that led to the resolution of the criminal case also leads to resolution of the civil case, as well.

You know, one of the features of any system of prosecution here in the United States is that the prosecutors are just afforded an enormous amount of discretion to determine how these cases are charged, to determine whether these cases are credible. So, in any instance, it’s incredibly important that you have a prosecutor who isn’t being totally unreasonable in the case. And for many, many years, that’s exactly the situation where Mr. Woodfox was in, where the principal decision maker, the prosecutor in this case, Buddy Caldwell, was just extraordinarily unreasonable. So, it was our view that anyone would have taken a more reasonable approach to the case and that a fresh set of eyes on this case would lead to a better result. And I think that that’s a big part of what happened.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert, can you give us a sense of your day? You’re in a—how large was your cell?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, CCR has moved around, you know, in the last 40 years. But basically, the nine—

AMY GOODMAN: CCR stands for?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Closed cell restriction.

AMY GOODMAN: So the size of your cell.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Nine-by-six, nine feet long, six feet wide. But we have been housed in cells smaller than that and some larger than that. You know, you try to develop a routine, and you try to, you know, keep changing it up, whether it’s the time or the content, the substance. You know, you just try to keep whatever you do connected to society. And it was very difficult for us because the very same people we were trying to help, usually these guys had a low level of consciousness, and so we had to try to be teachers, but at the same time we had to not allow ourselves to be sucked into the institutionalized vacuum that exists in prison. And so, you know, I don’t have a specific on how we survived. A lot of it had to do with us—for us, the influence of the party. You know, I’ve always said that the voice of the party was—for me, was stronger than the voice of the street. And it was when I began to change myself, to see myself in a different light—all of us, you know.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to bring Michael into the conversation, Albert Woodfox’s younger brother. Michael Mable, you met your brother as he walked out of the prison, and that’s the image to the world, of you and your older brother Albert walking out of jail. What was it like for you, after 45 years of the incarceration of Albert, to walk out with him as a free man?

MICHAEL MABLE: You know, it was unbelievable. I knew it was going to happen, but a lot of times reality don’t set in. I’ve been through this path with him over 40 years of visiting him, never lost the faith that one day it would happen. But, you know, sometimes you feel and sometimes you tell yourself it’s an illusion and it’s not reality. And reality really didn’t set in until I was able, because I had so many people ask me, “Well, how do you feel?” And it was a question that I couldn’t answer. The only thing I felt and only thing I can answer is that I know he’s a free man when I’m able to walk across the sill of the door with him. And that reality set in when we was able to do that.

AMY GOODMAN: You went to visit the grave of your mother with Albert, and your sister?

MICHAEL MABLE: Yes, I did.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was that like for you?

MICHAEL MABLE: It was—it was closure for him. I periodically always visit my mother’s grave. My mother took her last breath with me holding her hands. And I would always let him know how she went and how much, you know, she continues to look down and know that he’s going to struggle for the right thing in this world. And, you know, him and King and Hooks have always given me strength to go against the world and, you know, don’t matter what happens. It’s that if you continue with hope and strength, and you fight for a right cause, then you can do anything you want. And I held onto that. And that’s what pretty much kept our relationship, and I still today keep a relationship with Robert King. I call him my uncle.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert, you were describing in the first part of our interview your attempt to be with your mother when she was dying. Can you tell us again what happened at that time, what you were trying to negotiate and what happened?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, usually when someone loses a parent in prison, you know, they are allowed to go to the funeral and, you know, say goodbye, a cleansing of the soul. I found it very strange and very cruel that Warden Cain, who spoke about faith-based beliefs and how he changed Angola, that he could deny me the right to say goodbye to my mom, that I had to wait almost 20-some years to say—to be able to say goodbye, just to tell my mom in my heart and in my soul how much I loved her and that she would always be a part of me.

And, you know, when Michael and I—and one of the things that was frustrating is that the day I was released, by the time we got to the cemetery, it was closed, so I had to wait another day. And, you know, going to say goodbye to my sister and my childhood friend, who was also my brother-in-law, and—you know, it just wasn’t enough. I just had to see my mom. And once that was done, it was like this big weight was lifted off my soul. You know, one of the good things about Robert and I being with Herman is that we were both able to say goodbye. And I think that’s very important. It’s a big part of being a human being, you know, being able to say hello or being able to say goodbye to loved ones.

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re talking about Herman Wallace, the third of the Angola 3. You, Albert—

ALBERT WOODFOX: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —Robert King and Herman Wallace, you were together for the final time as Herman got word that he would be free. This was in 2013. He, too, had been in solitary for more than 40 years. He was dying of cancer, and the judge ruled that he had to be freed, above the objections of the prison warden, even threatening the warden with jail if he didn’t let Herman Wallace be free from Angola. And an ambulance was brought up to the prison, and Herman Wallace died a few days later, but in freedom. I wanted to bring Robert King back into this discussion. We asked Albert what it was like, even in shackles, to say goodbye to Herman. You complete the Angola 3. You were freed much earlier, in 2001, albeit after 29 years in solitary confinement. What was that moment like for you? You came into the prison as a free man to say goodbye to Herman, and Albert was brought in in shackles to say goodbye to your dying friend.

ROBERT KING: Yes, what a contrast, but it was—the fact that I was able to see him, you know, before he died and to kind of join in with the voice of Albert and the rest of the attorneys that he would eventually be freed, or he would be free that day, I think it was a good thing. He recognized that—he understood that it was he that—I think initially he thought we were speaking about Albert’s case had been overturned and gone free, but I think he eventually understood that it was him. And it was a good feeling to see the recognition in his eyes that he knew he was going to be free. So that was a good thing for me, and it gave—it gave me some hope to believe that Albert would also be free, but under different circumstances. And that did happen.

But while I was in CCR, my thoughts and sentiments about it wasn’t any too much different from—you know, from Albert. And if you want to know how I maintained, you know, some form of sanity, I think it was our—because of our political belief, I think. We had developed a political consciousness, and I think that kind of eliminated—that kind of aided us, gave us sort of like a board to hold onto, to cling to. We were in prison, but we didn’t allow prison to get in us. And there’s a difference. You know, of course, you suffer and you suffer the impact and the effect of prison, but, on the mind, you won’t let that distract you from your main purpose, your main objective. And the objective is to survive, and to survive in chains, though alter those conditions. And so this is what we were prone to do. We had no choice.

When you hit bottom, there’s no place but up to go. And Angola was the bottom. They even call it the bottom, and rightly so. And so, we were trying to get out that bottom. And ain’t but one way to get out the bottom, is to try to come up and do some things to kind of offset the situation, you know, the sad situation that was going on in prison. But it was a comfort also to our own mind. I mean, we were politicized. We had understood that we were—or why we were being targeted and punished, and this gave meaning to why we should struggle more so, because, you know, it was an unjust reason and unjust position we were in. And we had to struggle against this.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to play another clip of Herman Wallace, and this is from Herman’s House, the film. And this was Herman describing, on the phone from prison, a dream that he had. It’s not easy to understand, so everyone should listen carefully.

HERMAN WALLACE: I’ve had a dream where I got to the front gate, and there’s a whole lot of people out there. And you ain’t going to believe this, but I was dancing my way out. I was doing the jitterbug. I was doing all kind of crazy, stupid-ass [bleep], you know? And people was just laughing and clapping and [bleep], you know, until I walked out that gate. And I remember that dream, and I turn around, you know, and I look, and there are all the brothers in the window waving and throwing the fist sign, you know? It’s—it’s rough, man. It’s so real, you know. I can feel it even now, you know, talking about that.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, that is the film, Herman’s House, about a young woman named Jackie Sumell, who started to visit Herman in prison and designed with him his dream house, when he got out. Albert, as you listen to your friend, as you listen to Herman Wallace, who died in 2013 of cancer a few days after he was released from prison, your feelings, as he talked about people dancing when he got out of prison?

ALBERT WOODFOX: You know, I still haven’t quite come to terms with losing Herman. You know, I thought—somehow just it never seems right, no matter how I look at it, to suffer for so long and to finally win freedom, only to lose it. You know, I just—I just don’t have the words to explain. None of it makes sense, you know?

RENÉE FELTZ: Well, Albert, speaking of political prisoners, I wanted to ask you about your future plans and whether you, like your colleague, Robert King, also with us, plan to turn now to look at some of their situation. You yourself just turned 69 years old. There are many other people in prison now that were formerly associated with the Black Panther Party, the black liberation movement. What are your thoughts on many of them who continue to languish in prison now? Do you plan to look at their cases? And do you think you would be able to even get in contact with them, given that you, yourself, formerly incarcerated now?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Yeah, you know, both King and I, we feel our obligation to some of the comrades that’s still in prison, have been in prison for 30, 40 years. And, you know, thanks to the hard work that Robert did from the time he left Angola, it has given me the opportunity to take a couple of weeks or more to find out who I am and how I’m going to survive in society. But Robert and I—you know, the Black Panther Party may not exist, but we still exist. And we continue to—we will continue to struggle to free some of our comrades, and to, you know, stand shoulder to shoulder and try to take on all of the injustices that we can that goes on in America every day.

AMY GOODMAN: Robert King, you know, we met a few years ago when you came to New York, and we’ve interviewed you on Democracy Now! You were in solitary for 29 years. When you got out, I don’t think anyone would have faulted you for just getting as far away from prison as you could. But instead, you just kept on speaking about people who were still in prison, like Herman Wallace and like Albert Woodfox, right to the end. Why did you make that decision? What are your plans now, now that Albert is free?

ROBERT KING: To continue, to—as Albert alluded to a moment ago, to continue the quest. You know, it is of my own volition, it was my own free will, when I left prison, to do this. Like you said, Amy, you know, I could have—no, I couldn’t have. You know, I could not have just walked away. But it could have been a conscious wrong decision I made, had I walked away. And my dignity, you know, and my evolution would not allow me to do that. And even though I did not know what I would do, no way in the world I could come out into society and live a sedated lifestyle once I was released. And since Albert is released, I won’t be living a sedated lifestyle. I found my niche. And again, like I say, it’s of my own volition, and I will continue to do this. And this is my quest, because there are other people in prison who will face another generation or two generations of people who are facing the same thing that Albert and I and Herman faced for decades and many more, people whom you haven’t even heard of. And so, the struggle continues. That’s the quest.

AMY GOODMAN: And what gives you hope, King? What gives you hope, Robert King?

ROBERT KING: What gives me hope is that, you know, if you throw a pebble in a pond, you get ripples. You get a wave after a while, if many people throw pebbles in a pond. The pebbles that we threw in a pond got the ripples, and Albert was washed out the other day. And we are hoping just that other people will be, again, washed out the same way as Albert was.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert, let’s end with you on that question: What gives you hope? You have been in solitary confinement longer than any prisoner in the United States, 43 years, freed on your birthday, February 19th, just a few days ago.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, honestly, what gives me hope is King. And he could have quit anytime. In 15 years or more, he has never broke faith. He has struggled for my freedom. My brother, who has supported me for 47 years, has never missed a month of coming to see me. There have to have other human beings like my brother and my best friend in this world, and they are going to need help, and they’re going to need support. So my hope is to find some of these men and women, and in the case, young kids, and be as instrumental and having some type of influence in the direction they go and the value system that they may develop or to develop principles of the highest standard. I think humanity is not as bad as it could be, but it’s not as good as it should be. And I can play a very big part in doing that.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you all very much for being with us. Albert Woodfox, congratulations on your freedom. Robert King, thank you for joining us. Both men in solitary confinement for decades, Robert King for 29 years, Albert Woodfox for 43 years. And thank you to Michael Mable, Albert’s brother, for joining us today, and to Billy Sothern, Albert’s attorney.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Thank you very much.

ROBERT KING: Thank you.

BILLY SOTHERN: Thank you.

MICHAEL MABLE: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Renée Feltz. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options