Topics

Guests

- Steve Shapiroprogram director for Mosaic, a high school humanities program that draws students from across Columbus, Ohio.

- Jacob Seitzsenior in the Mosaic program.

- Mashal Ahmedsenior in the Mosaic program.

- Cassidy Boyukfirst-year student in the Mosaic program.

- Cassidy Boyukstudent in the Mosaic program.

- Jess Flowershigh school junior in the Mosaic program.

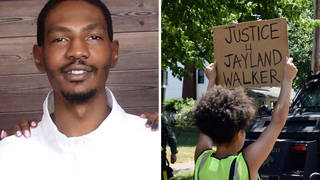

We end today’s show remembering Black Lives Matter activist MarShawn McCarrel. On February 8, he shot himself to death at the entrance to the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, Ohio. MarShawn McCarrel was just 23 years old. MarShawn organized against the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson and worked to aid the homeless. He launched the program Feed the Streets after he himself was homeless for three months. Hours before he shot himself, MarShawn wrote on Facebook, “My demons won today. I’m sorry.” Just days before his death, MarShawn was honored as a Hometown Hero at the NAACP Image Awards for his community project, Pursuing Our Dreams. On Tuesday, Democracy Now! spoke to a group of students and a teacher who knew MarShawn.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We end today’s show remembering Black Lives Matter activist MarShawn McCarrel. On February 8th, he shot himself to death at the entrance to the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus, Ohio. He was just 23 years old. MarShawn organized against the police shooting of Michael Brown of Ferguson and worked to aid the homeless. He launched the program Feed the Streets after he himself was homeless for three months.

AMY GOODMAN: Hours before he shot himself, MarShawn wrote on his Facebook page, “My demons won today. I’m sorry.” Just before his death, MarShawn was honored as a Hometown Hero at the NAACP Image Awards for his community project, Pursuing Our Dreams.

When I was in Ohio yesterday, in Columbus, I spoke to a group of high school students and their teacher, who knew MarShawn well. Steve Shapiro is the program director for Mosaic, a high school humanities program that draws students from across Columbus, Ohio.

STEVE SHAPIRO: Mosaic is a high school humanities program for creative young people from across Franklin County. And MarShawn was not only an amazing kid as a student, but he came back many years as a guest speaker for us. He spoke not only about activism and about strategies for making social change, but he also spoke about white privilege and about racial questions. And he was a brilliant, brilliant guy and someone that our kids fell in love with every time they saw him.

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re the head of the program?

STEVE SHAPIRO: Program director.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you meet MarShawn?

STEVE SHAPIRO: Like we meet all of our students—going out and recruiting and sharing information about this program. And I think MarShawn saw—as a creative and a socially conscious young man, saw this as a really unique opportunity, but also recognized himself as being not like many of the other kids who came from privileged suburbs. And I think he wondered, “Is this the right place for me? Am I outside of my comfort zone?” And I think it was an act of courage for him to choose to come to Mosaic, because, you know, as he said, “I’m one of the homies here,” but there aren’t many, you know, and he stood out, and it was a risk. But he found very quickly that he was in a culture of people who really valued and cared about him.

AMY GOODMAN: He started a program with his brother?

STEVE SHAPIRO: Yeah, MarShawn and his brother, his twin brother MarQuan, started the program called Feed the Streets, which is basically a program on the West Side, in the Bottoms, near where they came up, and basically was a program where they were feeding people in their community, but it wasn’t a community service, it wasn’t a charity act. It was basically a building community act. MarShawn always believed you have to build community to move community. And so, what he and his brother did was organize people. Usually, as many as 40, 50 people would show up once a month to just pass out lunches, not so much as an act of charity, but as an act of connecting with neighbors. People would go door to door. People would say hello to people. People would just sort of build a positive relationship between strangers in the community, to make the notion that people could be safe, that people could be together, and that people, all different types of people, are welcome in the Bottoms.

AMY GOODMAN: It must have come as a terrible shock to you. How did you hear that MarShawn had died?

STEVE SHAPIRO: I mean, of course, on Facebook, like you hear everything, is the first time I saw it. And I think I was really in a pretty deep state of denial the night that it happened, and I thought maybe it’s a mistake, maybe it was misreported.

AMY GOODMAN: What did he say on his Facebook page?

STEVE SHAPIRO: Well, on his Facebook page, he said, “My demons won today. I’m sorry,” which was ominous. But, you know, it was just the reality that—the reason it was so shocking to me is MarShawn was full of life. He had a bright smile, flash in his eyes. Everyone loved him. He could light up a room. And he always seemed to be positive and working. You know, he was a kid—a young man that could see all the oppression and injustice, commit himself to working for it and still just bring light and life. Like he never—he wasn’t—even if he was angry at the system, he managed to somehow bring a positive energy to the work that he did. He was remarkable.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell me your name and how you knew MarShawn?

JACOB SEITZ: I’m Jacob. I learned about MarShawn through the Mosaic program.

AMY GOODMAN: Are you in it?

JACOB SEITZ: Yes, I am. I’m a senior. It’s a two-year program, and this is my second year of it.

AMY GOODMAN: A senior in high school.

JACOB SEITZ: Mm-hmm, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you know MarShawn?

JACOB SEITZ: Well, MarShawn had come in multiple times to talk to the Mosaic program about the importance of activism and the importance of kind of getting out in your community. And I kind of learned about him through that. And he personally, at least for me, inspired me to be an activist. You know, I’ve held, personally, rallies at local Planned Parenthoods for—against like anti-choice groups. And he just inspired me to really go out and kind of help my community. One of my favorite quotes he said—he said he always wished he had a gun that shot hope, because he would light up the hood, which I just think is—like epitomizes him, for me.

AMY GOODMAN: There was an unfortunate incident, after he died, with a police officer. Can you explain what happened?

JACOB SEITZ: Well, yeah. A police officer—I believe it was near Dayton—reposted an article that he found about MarShawn and with a comment, you’ve got to “Love a happy ending,” which just set a lot of people off. And it was just really upsetting to see law enforcement treat someone who was so afraid—he was so afraid of law enforcement because of where he grew up. You know, he grew up in the West Side of Columbus, which has been notorious for not very good treatment of people by the police. And so, I think that it was just—it was really sad for a lot of people to see mistreatment like that.

AMY GOODMAN: The police officer wrote, you’ve got to “Love a happy ending,” after MarShawn had committed suicide.

JACOB SEITZ: Yeah, yes, he reposted one of the articles on Facebook that was talking about MarShawn, who had committed suicide on the Statehouse steps.

AMY GOODMAN: Who—what happened to him?

JACOB SEITZ: He was put on paid leave, because—I would like to think that if he wasn’t unionized, there would have been stricter actions. But he was put on paid leave by the police department of that city.

AMY GOODMAN: Have there been protests?

JACOB SEITZ: There have not. I think MarShawn’s family is asking people to kind of focus on how he lived his life rather than how he died. So…

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell me your name and how you knew MarShawn?

MASHAL AHMED: I’m Mashal Ahmed. I’m a senior in Mosaic, and I knew him from him coming in and speaking to us multiple times, and going after class and speaking to him one on one, and actually going to one of his Feed the Streets events and going and passing out food to people.

AMY GOODMAN: What is Feed the Streets, the program he started with his twin brother?

MASHAL AHMED: Well, basically, it’s a program that, once a month, people come together, and they have—they have brown paper bags filled with sandwiches, water, snacks. And they go around in the West Side and just offer people a meal. And if people decline it, we let them be. And if they accept it, we give it to them. And one of the things that MarShawn would say before I went out there, that really spoke to me, was, “The hood doesn’t need heroes. They need neighbors.” And so, he would always talk about how we’re not above these people, we’re not their saviors, we’re not like better than them; we’re just here trying to build a community. That’s what we’re trying to do. We’re supposed to come together as one. And I think I’ve tried to do many charity events, and nothing that I’ve been through—gone to has been anything like that and what MarShawn had said.

AMY GOODMAN: MarShawn was being honored by the NAACP as a Hometown Hero?

STEVE SHAPIRO: Yeah, in fact, just days before MarShawn’s passing, he was in Los Angeles to be recognized as a Hometown Hero. And so, again, that was part of the surprise of the whole thing, is his work was so impactful, he was making such a difference, he was being recognized. But I think MarShawn just cared so much that I don’t know if it was—anything he could do was ever enough to solve the things that were so important to him.

AMY GOODMAN: And what’s your name? And are you part of the high school program?

CASSIDY BOYUK: I’m Cassidy. Yeah, I’m a first-year student in Mosaic.

AMY GOODMAN: And how did you know MarShawn?

CASSIDY BOYUK: Like they said, MarShawn came in, and he would talk to us about privileges—white privilege, male privilege. And I think he taught me more about privilege than anyone I’ve ever met. I met him originally at a Black Trans Lives Matter protest, and he spoke there, but only after he had been asked. And then later, when I met him in Mosaic, he was speaking on privilege. And he said, “Show up and shut up.” And that was like a main thing—everyone in Mosaic talks about it now—that you show up to these things, and you’re a number, and you’re there, and you’re part of the movement, but if it’s not your place, you don’t speak on it. You speak to people of your privilege, but you don’t speak to people who are running the movement, because they’re the leaders of the movement. You know what I mean? And I think that was like a main thing that I really have held onto. I’ve been protesting more lately, and I think things like Feed the Streets—Chloe and I went to Feed the Streets, and it was just amazing to see what he did for our community, the people that he helped, everyone who remembered him. He had such an impact on everyone who met him.

CHLOE CHALLACOMBE: My name is Chloe Challacombe.

AMY GOODMAN: And how did you know MarShawn?

CHLOE CHALLACOMBE: I first met MarShawn when he came into a white privilege panel to speak at a Mosaic event for class.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did he teach you?

CHLOE CHALLACOMBE: Well, he told this story about—that really, really opened my eyes to white privilege. He talked about how he was at a football game one night. And it was really relatable; I remember like running around football games myself. But he talked about how he was causing some trouble, and a police officer pulled him aside, and he kind of called him out on it, and then he drove him home. And he had to tell his mom. And his mom just started crying, like she wasn’t mad at him or anything. She just was crying and sobbing. And she said to him, “Son, these white people will kill you.” And that was something that just really resonated with the group, and like people are still repeating it to this day. And like, I can just hear it, like I can just hear it in his voice. And it was just like—it silenced the room.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell me your name.

JESS FLOWERS: Jess. I’m a junior in high school with the Mosaic program.

AMY GOODMAN: How old are you?

JESS FLOWERS: Seventeen.

AMY GOODMAN: And when did you meet MarShawn?

JESS FLOWERS: I met MarShawn at our first privilege panel in our very first project, which was white privilege. And he spoke about everything he had been through, just as Chloe had mentioned. And what really struck me was, at the very end, I had gone up to him to talk to him about being white passing, because I am biracial, and how I never really went to Black Lives Matter events because I felt as if I didn’t belong there, I wasn’t valid in my identity, you know, that people would look at me weird and just think, “Oh, why is this white girl here?” And my favorite memory is just how he looked me in the eye, and he was like grinning ear to ear, and he said, “You’re just as valid as me. It doesn’t matter about the color of your skin.” And to have someone say that to me for the first time in my life, it meant a lot to me.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about this issue of MarShawn’s suicide? How are you dealing with this? All of you knew him. He went through your program. He was your age. Can you talk about his death, the steps of the Statehouse in Columbus, Ohio? Maybe I’ll turn to the teacher, Steve Shapiro.

STEVE SHAPIRO: I mean, obviously, choosing the steps of the Statehouse was a political statement. But I think most people are remembering MarShawn for what he did and what his work was. And in all of the memorials afterwards, everyone’s commitment was to carry on MarShawn’s work, to take what he was passionate about and what he was committed to, and each of us rededicate ourselves to creating a more just and more fair, more equitable world. And so, I think that’s what we’ve all taken, is how do we live MarShawn’s passions in his absence.

CASSIDY BOYUK: I think our teacher Kim, our other teacher, said that—everyone was saying “rest in power,” which is something that people typically say when activists die, but she said, “Don’t let his power rest. Let it live in you, and continue his movements.” And I think that’s something that everyone is trying to do, because he meant so much to everyone.

AMY GOODMAN: High school students in Columbus, Ohio, remembering their mentor and friend, Black Lives Matter activist MarShawn McCarrel, who committed suicide on the steps of the Statehouse February 8th. Special thanks to Professor Jeffrey Demas of Otterbein TV.

That does it for our broadcast. We have three job openings. Check our website at democracynow.org.

Media Options