Guests

- Dave Isayfounder of StoryCorps and author of the new book, Callings: The Purpose and Passion of Work.

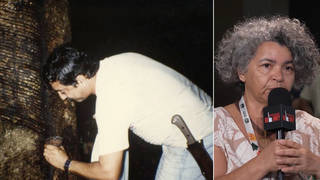

We spend the hour with Dave Isay, the founder of StoryCorps, the award-winning national oral history project. In a 1989 radio documentary, “Tossing Away the Keys,” he chronicled the case of Moreese Bickham, a former death row prisoner who recently died at the age of 98. In 1958, Bickham, an African American, was sentenced to death for shooting and killing two police officers in Mandeville, Louisiana, even though Bickham said the officers were Klansmen who had come to kill him and shot him on the front porch of his own home. Many other people in the community also said the officers worked with the Ku Klux Klan, which was a common practice in small Southern towns. Moreese Bickham served 37 years at Angola State Penitentiary, in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day.

He won seven stays of execution, but Louisiana’s governors repeatedly denied him clemency until, under enormous pressure, he was finally released in 1996. Days after he was released, he traveled to New York, where he was interviewed on WBAI’s “Wake-Up Call” by Amy Goodman, Bernard White and others. “Wake-Up Call” had closely followed Bickham’s case and helped give it national attention. We play an excerpt from the interview for Isay and discuss Bickham’s life and legacy.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today we spend the hour with Dave Isay, the founder of StoryCorps. Over the last 12 years, StoryCorps has gathered the largest single collection of human voices. In 2003, the first StoryCorps recording booth opened in New York’s Grand Central Station. Since then, a quarter of a million people have recorded interviews with their loved ones through StoryCorps.

Dave has just published a new book titled Callings: The Purpose and Passion of Work. Amy Goodman and I recently interviewed Dave Isay about the book, but we began by discussing the case of Moreese Bickham, a former death row prisoner who recently died at the age of 98. In 1958, Bickham, an African American, was sentenced to death for shooting and killing two police officers in Mandeville, Louisiana, even though Bickham said the officers were Klansmen who had come to kill him and shot him on the front porch of his own home. Many other people in the community also said the officers worked with the Ku Klux Klan, which was a common practice in small Southern towns. Moreese Bickham served 37 years at Angola State Penitentiary, in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day.

Dave Isay chronicled his story in the 1989 radio documentary, Tossing Away the Keys. Bickham won seven stays of execution, but Louisiana’s governors repeatedly denied him clemency until, under enormous pressure, he was finally released in 1996. Days after he was released, he traveled to New York, where he was interviewed on WBAI’s Wake-Up Call by Amy Goodman, Bernard White and others. Wake-Up Call had closely followed Bickham’s case and helped give it national attention. We began our interview with Dave Isay by playing for him Moreese Bickham in his own words.

MOREESE BICKHAM: I was shot through the heart with navel string shot off, and I asked the lord, I said, “Lord, I know you’re good, God, and you made one promise: Honor thy father and thy mother, that thy days be long in the land which the lord thy God giveth thee.” I said I might have not been an obedient child, but I tried. And said, for that reason, allow me to have a few more days. And he did. From that day—I had a good walk with God, but I never had a personal relationship with him until I was laying at the point of death with a bullet shot top of my heart all with. He showed me that I was going to get up. In 48 days, I’m up and working. When I got shot in '52, I asked the lord, I said, if it ever be anything else like this, give me something to shoot; let the other man die, not me. Six years from that day, I was reminded of those words, and I got into it that time, and I have served 37 years for it. I could at least say to the lord, “Don't let this happen anymore.” And it wouldn’t happen. But I was a person that didn’t see but one way, and that was my way. It wasn’t God’s way. And I’ve told many ministers and many people that there’s something hidden in my head told me to do what I did. And they say, “Oh, no, the lord ain’t never told you.” I said, well, you—I know there wasn’t no spirit in the world tell me to do something and, when it’s over, said everything going to be all right, and I live through seven stays of execution, all the heart attacks and operations I had, and come out in good enough health to be flying all over the world. Nobody can tell me God wasn’t on my side.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Moreese Bickham in the studios of WBAI. It was back in 1996. The studio was packed. I remember it so well. It was Martin Luther King Day. And he came in with his family, with his daughter. I think his grandson might have been there. The late, great Gil Noble was there. Of course, Bernard White and I, we hosted Wake-Up Call. But, Dave Isay, you had really shown the spotlight on Moreese’s case when you did a documentary on Angola. Talk about the significance of Moreese Bickham, who just died at the age of 98.

DAVE ISAY: Well, I remember that day well. I just watched the video last night that TV viewers saw. And it was—it was an incredible moment with all of us sitting there, because you—WBAI had been fighting for his release for, I think, a year, every day pounding, pounding for his release. And there we were—

AMY GOODMAN: Right. We would say, “Is Moreese Bickham free yet?”

DAVE ISAY: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, Bernard White, Errol Maitland: “Wait, has Moreese Bickham gotten out of jail yet?”

DAVE ISAY: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: I think the—even the Louisiana attorney general or the governor talked about the significance of this radio station.

DAVE ISAY: Yeah, it was—and, you know, I think every day you would play the Nina Simone song, “I Wish I Knew How It Feels to Be Free.” And sitting in that room with Moreese with his headphones on as he rocked back and forth, 48 hours after getting out, you know, listening to that song with his kids and his grandkid, crying, was just one of the most remarkable moments, I think, of my life. So, he was a—I mean, it was an absolutely insane case. I mean, these two sheriff’s deputies had come to his house.

AMY GOODMAN: This is in the 1950s.

DAVE ISAY: Yeah, in the '50s. And they had come to kill him. And they shot him right above the heart, and he rolled over on a gun, and he killed the two of them. And he actually talks, in that interview—because I watched last night this thing from 20 years ago—and he talks about how one of the—the kid and grandkid of one of the officers he shot was visiting him, back then, in the ’50s, saying, “You shouldn't—you should not be here.” And now, you know, there’s a granddaughter of one of the officers who was killed, who has been trying to apologize to Moreese and never got a chance, because he was 98 when he died, and he was too sick.

AMY GOODMAN: These deputies were so determined to kill Moreese Bickham, coming to his house, that they wore their sheriff’s clothes over their pajamas.

DAVE ISAY: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: They came in the middle of the night.

DAVE ISAY: That’s right. And I heard—they claimed that they had to kill him because he was angry for not allowing—them allowing him to get into the car with them or something, like just some absolute craziness.

AMY GOODMAN: But, Dave, you—

DAVE ISAY: He was a fine, fine human being.

AMY GOODMAN: You had discovered him when you did your documentary, Throwing Away the Keys.

DAVE ISAY: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: About Angola.

DAVE ISAY: Thirty years ago, yeah. So he was one of these guys who had been in Angola serving the longest prison sentences in history. And he cared for the rose bushes at Angola and was just—just a—

AMY GOODMAN: A plantation prison.

DAVE ISAY: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: Named for the country in Africa where so many people had become enslaved in this country, had been taken, kidnapped from Africa. And the plantation was named for the country that the Africans had been taken from.

DAVE ISAY: And there were a bunch of men who had been—who had been there for longer than anyone else in history. And some of these men had actually—this was not the case with Moreese, who had spent all of his time on death row, but there were many men who had been brought in and told to plead guilty to whatever crime they had been accused of, even though many of them hadn’t committed them, because if they went to trial, they’d get the death penalty. And there was a law back then that the rule was you got out after 10 years on a murder. And then they changed the law when some of these guys were about to get out. So you had people serving 30, 40, 50 years for crimes that they hadn’t committed, because they were trying to save their lives. And Moreese had spent all this time on death row. And it was just—you know, he was a minister. He told the story of getting old in prison, how he became Pops—that was his name from when he was a young man—how he’d had to pretend he was crazy on death row, going into psychiatric hospitals, because it was the only way to avoid the death penalty. And he was an amazing man. And more amazing than that, he got out 20 years ago, and he lived ’til the age of 98, by himself, independently, in Oakland, with his family.

AMY GOODMAN: In California.

DAVE ISAY: Yeah, and was just—was just a remarkable man.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: That was StoryCorps founder Dave Isay. We’ll be with him in a minute.

Media Options