Guests

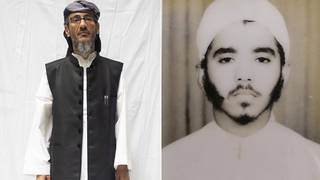

- Jihad Abu Wa'el Dhiabformer Guantánamo prisoner.

- Ramzi Kassemprofessor of law at the City University of New York School of Law, who represented Dhiab and many others at the prison, and helped him be released.

We go to Uruguay for an exclusive interview with former Guantánamo prisoner Jihad Abu Wa’el Dhiab as he continues a hunger strike demanding he be allowed to leave the country in order to reunite with his family, and we speak with attorney Ramzi Kassem, professor of law at the City University of New York School of Law, who helped win Dhiab’s release and represented many others at the prison.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we go now to Uruguay, where former Guantánamo prisoner Jihad Abu Wa’el Dhiab continues a hunger strike demanding he be allowed to leave Uruguay in order to reunite with his family in Turkey or in another Arabic-speaking country. Dhiab was imprisoned in Guantánamo for 12 years, cleared for release under both President Bush and President Obama. He has never been charged with a crime.

While at Guantánamo, Dhiab also launched a hunger strike to demand his freedom. He was among a group of prisoners subjected to force-feeding. The Obama administration is refusing to release video of the force-feeding to the public, but after a judge demanded it, the Obama administration did give the redacted videotape to the court, which reportedly shows graphic images of guards restraining Dhiab and feeding him against his will. Human rights groups have long said the force-feeding of Guantánamo prisoners amounts to torture.

Well, last Wednesday, Dhiab slipped into a coma for nine hours on a hunger and thirst fast, revived only by a hydrating IV while he was in that coma. On Thursday, after nine hours in the coma, Dhiab awoke, and I was able to speak to him in an exclusive Democracy Now! interview. He was exhausted. He was lying on his bed in Montevideo, Uruguay. And I asked him to begin by talking about how he felt.

JIHAD ABU WA’EL DHIAB: I feel really very, very worse. All my body hurt me, and my kidney, my headache, my stomach, my right side really bad. Many things. But I feel all my body hurt me.

AMY GOODMAN: There’s a battle in court in the United States to release the videotape of your force-feeding in Guantánamo. Can you describe what that force-feeding was like for you?

JIHAD ABU WA’EL DHIAB: Like the United States always say in the media, “Human rights, human rights, human rights.” There’s never in Guantánamo, don’t have any human rights. Never, never, never. He took the video from first time go to me in my cell to move me to chair and give me the tube for give me forced feeding. But if you see this video and see the guard, how treatment with me, how beat me, how make with me, that’s not human.

AMY GOODMAN: Dhiab, in Guantánamo, one nurse refused to force-feed the prisoners. Can you talk about that nurse?

JIHAD ABU WA’EL DHIAB: This nurse, from first time come into Guantánamo, me and my brother spoke with him many time. “Why you come in here? This your job, this human right job, a good job. Why come in here for torture the person, the detainee?” He think, think, think too much. After that, he said, “Give me couple days. I take decision for that.”

He, after two days or three days, come and tell me, “Jihad, there I don’t leave anyone tell me my number, because I am not number, I have name.” He tell me, “Jihad, I take decision.” I tell him, “What?” He said, “Now I stop give any force-feed for anyone. I refuse to give any. And I spoke with the government in the Guantánamo about this.” I tell him, “Me and all my brothers said for you, thank you very much for that,” because I respect this person very—he helped me, and he a gentle man. He treatment with us there—only him, treatment with us from first day coming there. I see him always, he not all right. And he treatment with us very, very well. And after that, I tell him, “Thank you very much about this.” He said, “What’s happened after that, I don’t care, but I don’t—I refuse give any force-feeding.”

And after that, he move from there. And I hear after that in the news they want to take him to court about he refused—because he refused the Army order. But I respect this person. I need all the person make like him and treatment like him, because this all right idea.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama says he wants to close Guantánamo. Do you believe that will happen?

JIHAD ABU WA’EL DHIAB: If he wants to close Guantánamo, he can. He can now. Now. He can give order, close Guantánamo. He can close Guantánamo. But he coward. He can’t take this decision, because he scared. But Guantánamo supposed to close, should be closed, Guantánamo, because Guantánamo, that’s not good for the United States. Never.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Jihad Abu Wa’el Dhiab, speaking to us in English from his bed in Montevideo, Uruguay. He’s been on a hunger strike and had just come out of a nine-hour coma after refusing water. Throughout our interview, which we did just after he revived, he was very tired and weak. He would sometimes switch to Arabic from the English, the language he felt he could express himself better in. This is Dhiab speaking about why the U.S. wouldn’t want to release the video of his force-feeding at Guantánamo and more.

JIHAD ABU WA’EL DHIAB: [translated] The U.S. does not want the world to see the truth about what happens in Guantánamo. They want to keep the black box closed and to show instead that the black box is full. But it is indeed actually empty and a lie. They can’t let the world see the video and know the truth, because the truth will contradict the reasons the U.S. is holding the prisoners.

For example, I have papers showing to be innocent since 2006, since the time of George Bush, yet they kept me in Guantánamo. And again, I had papers proving my innocence in 2009 with Obama now president, but they still kept me in Guantánamo. I ended up staying until December 2014. And even the media started to report on me, saying that I was a victim and that I was an innocent man that didn’t do anything wrong. In Guantánamo, they said I will not get out until I admit a crime. This is the fact of America. You have to admit to any crime. Why? I said I will not admit to anything. I didn’t do anything. That is number one. But they will not say up front to their people, “We caught innocent people who didn’t commit any crime.” They had to create anything. They must force us to admit anything. They offered multiple choices for us to admit something. Is that justice? The issue is, the United States knows it’s wrong and implicated in Guantánamo, but the U.S. does not want to apologize and go back and stop this injustice and solve this problem.

With this, I want to send a message to the American people about the American government’s policy, with Muslims and non-Muslims, because their policies with Muslims will bring a lot of problems. America is who creates enemies for themselves. America is who creates terrorism and hostility toward themselves.

AMY GOODMAN: Dhiab, are you willing to die on this hunger strike?

JIHAD ABU WA’EL DHIAB: [translated] I can only see two solutions: Either I am reunited with my family or I will have to pay with my life. I want to reach my family, that I have not seen for 15 years. I didn’t see any of them—my mother, father or brothers and sisters. I lost my son in war in Syria, and 28 others of my family died, as well. My entire family is spread out in different countries, leaving no one with my parents. This is a very complicated issue. I want my right to live a good life and to be free.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Jihad Abu Wa’el Dhiab. He was held at Guantánamo for more than 12 years, has not seen his family for between 15 and 20 years, his parents, speaking to us exhausted from his bed in Montevideo, Uruguay. He’s been on a hunger strike and had just come out of a coma last Thursday morning, after refusing water, that he had been hydrated through an IV, extremely weak and tired.

For more, we’re joined by Ramzi Kassem, professor of law at City University of New York School of Law—that’s the CUNY Law School—where he directs the Immigrant & Non-Citizen Rights Clinic, has represented many Guantánamo prisoners.

You have been to Guantánamo for—oh, many, many times, about 50 times. You were one of the lawyers who represented the six Guantánamo prisoners who the U.S. government released to Uruguay. Can you tell us about Dhiab’s case, why he hasn’t been able to see his family, what he is asking for, what he was promised, and what the situation is overall at Guantánamo?

RAMZI KASSEM: Yeah, so I’m among the people who negotiated. Obviously, there were U.S. government officials involved, Uruguayan government officials involved. And then, on the defense lawyer side, I was one of those who partook in that negotiation, primarily on behalf of my client, Abdelhadi Faraj, who’s another Syrian who was resettled in Uruguay, just like Dhiab. Ultimately, what happened was that four Syrians, one Palestinian, one Tunisian—all Guantánamo refugees—were resettled in Uruguay.

And, you know, I have to stress that the Uruguayan government’s attitude towards these men was commendable. They viewed them and treated them as refugees under international law. They resisted, you know, the United States’ insistence that their movement be restricted, that they be treated as something else, that they be placed under surveillance, for example. All of these things, according to public media reports, are standard when it comes to how the United States negotiates these repatriations or resettlements from Guantánamo. And to their credit, the Uruguayan government said, in large part because the rulers of Uruguay at the time, the president and his Cabinet, were themselves former political prisoners—

AMY GOODMAN: President Mujica.

RAMZI KASSEM: President Mujica had spent over a decade in prison under that very label, as a terrorist, in solitary confinement, so he understood, and the men in his Cabinet understood, what that meant. And so, to their credit, they treated these men like refugees. And they said—they said that they would allow them to reunite with their families in Uruguay, that they would facilitate family reunification. So all of the right things were said.

Unfortunately, the problem was in the implementation. When the men arrived in Uruguay, you know, less preparation had been done than what we had expected and what we had hoped. And one of the main shortcomings is on this front—family reunification. In other words, you know, the government of Uruguay, with the help of the Red Cross, is offering families of men like Dhiab and men like my client to come from places like Syria or refugee camps in Turkey. But they’re only offering temporary visits, and they’re not giving the men the means to actually support those families in Uruguay. So, the net result, and I’ll tell you the case that I—I’ll tell you about the case that I know best, my client, Mr. Abdelhadi Faraj. His family is in war-torn Syria. He would love to see his parents. He hasn’t seen them in 15 years. If he were to agree to have the Red Cross somehow try to bring them, make that very dangerous journey out of Syria and to Uruguay, he can only keep them there for a couple of weeks. His parents are elderly. They live in a very dangerous place. The trip itself would be life-threatening. So he doesn’t want to subject them to that risk, unless he has the ability to actually have them live with him in Uruguay. So, that’s where the shortcoming has been. No one, not the Uruguayan government and certainly not the United States, has stepped up to make that happen.

And I mention the United States because I think the Uruguayans have gone above and beyond the call, in many ways, despite the shortcomings of in preparation for the arrival of these men as refugees from Guantánamo. They have gone above and beyond the call. The bulk, the lion’s share, of responsibility still rests with our country. It still rests with the United States. Our country is responsible for what happened to men like Dhiab. They’re the ones—the United States took Dhiab and put him at Guantánamo and subjected him to torture there, of different forms. And the United States is the one that—

AMY GOODMAN: And he was put at Bagram first.

RAMZI KASSEM: And he was at Bagram first. And that’s common. The majority of Guantánamo prisoners, or a large number of them, at least, went through Bagram or other sites before arriving at Guantánamo. So the primary share of responsibility still rests with the United States. I believe that our country has a moral and historical duty to try to make these men whole. Other countries have. Canada has paid compensation. The United Kingdom has paid compensation. The United States has not accepted responsibility or compensated these men for what they have been through. And they continue to suffer from it—for it, and their families continue to suffer. And Dhiab is just one example among many.

AMY GOODMAN: Dhiab was—wanted to be at his daughter’s wedding. I mean, he hasn’t seen his children and his parents in between 15 and 20 years. Could he leave Uruguay? I mean, he actually attempted to. He went to Venezuela. He was taken by the secret police of Venezuela, and he was deported back to Uruguay. I mean, it’s not a crime for him to leave Uruguay, but he was deported back. What can he do? I mean, he is just using the only thing he has, which is his body, to try to demand, by going on a hunger strike, which he did for so long at Guantánamo, to demand some kind of action. He says, “If I am free, why cannot I see my family?”

RAMZI KASSEM: And it’s especially tragic that he’s had to revert to that mode of communication, the mode of communication that he had when he was at Guantánamo. In other words, the only form of expression and protest available to many of the prisoners is to go on hunger strike, is to refuse food and sustenance from their captors. And that isn’t a crime, right? It’s a form of peaceful protest. And it is tragic that now that he’s in Uruguay, supposedly a free man, he feels that he has no choice but to do that in order to be heard, because, you know, he’s been clamoring for a while. They’ve been in Uruguay for almost two years. And for that entire time, Mr. Dhiab and the other prisoners have been asking this question. You know, when are we going to see our families? Is that going to happen? How is that going to happen?

The Uruguayans, when these men arrived, because they were considering them refugees, the Uruguayan government issued them what’s called a cedula, which is basically a national ID card, which allows them to travel in certain countries in South America and some countries in Central America, perhaps. So that’s how Dhiab, earlier in his tenure in Uruguay, went to Argentina, for example, and gave a press conference there. And that’s probably part of the explanation of how he eventually got to Venezuela and was then sent back to Uruguay. The rub is in that for him to go to Turkey, the Turkish government would have to acquiesce. Someone would have to facilitate that travel. He’d have to be issued travel papers, which obviously he’s not going to get from the Syrian government, given what’s going on in Syria right now, and, ultimately, the United States government, whether or not they’re going to publicly recognize it. My view, my opinion, is that the United States government probably has a say, as well.

Now, still, the right thing to do here is to find some way to reunite Mr. Dhiab with his family. And it’s either by bringing his family over from that refugee camp in Turkey to Uruguay in a sustainable fashion, where they can live with him in Uruguay and make a life for themselves there, or the other solution would be for him to go to Turkey and join his family there. It is—it’s compounding the injury that these men have suffered to keep them apart from their families after everything that they’ve been through. And again, this doesn’t just hold for Mr. Dhiab. He is being vocal, vocal and brave, in expressing his protest in that way. But I can tell you that my client, Mr. Faraj, who does not want to be in the media limelight, feels the same way. And the other prisoners that he’s still in touch with in Uruguay, former Guantánamo prisoners, they feel the same way, as well. And it’s really—it shouldn’t be shocking to anyone that these men, after all of these years, wish to see their families. Guantánamo is not a prison where families can visit. It’s not like a facility here in the United States where there are visitation privileges and people can come over the weekend. These men have literally not seen their families for over a decade and a half.

AMY GOODMAN: Have some of the men seen their families brought to Uruguay, and then they have to leave?

RAMZI KASSEM: You know, I’m not familiar with the cases of all six of the Guantánamo refugees in Uruguay. I can tell you that for Mr. Dhiab that hasn’t happened, and I can tell you that for my client, Mr. Faraj, that has not happened, for the reason that I explained earlier.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you have been to Guantánamo for what? Like 50 times now, representing your clients. How many do you represent?

RAMZI KASSEM: At this point, I have three clients remaining at Guantánamo. Over time, since 2005, I’ve represented over a dozen Guantánamo prisoners.

AMY GOODMAN: That, what, you added it up to what? Being how much time at Guantánamo that you’ve spent?

RAMZI KASSEM: Sadly, I did that math last time I was at Guantánamo a couple of months ago. It adds up to, I think, over a year at this point.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve spent over a year at Guantánamo.

RAMZI KASSEM: Yeah, which obviously pales in comparison to what my clients have spent, what they have gone through. But it was still shocking to me. I mean, if you told me 10 years ago, in 2006, when I made my first trip to Guantánamo, that a decade later I’d still be traveling there, I would have called you crazy.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama just said, once again, he wants it closed by the end of his term. Do you think this will happen? What is happening at Guantánamo right now?

RAMZI KASSEM: You know, President Obama, unfortunately, has been saying that since he was candidate Obama in 2007. You know, I agree with Mr. Dhiab on this. I believe that, unfortunately, our president has had that authority. He was elected, actually, on that basis. He had a mandate coming into office in 2009 to close that prison. For political reasons, not policy reasons, but for political reasons, he chose not to make it a priority. He gave the opposition time to mobilize and make it more difficult for him. Still, despite those obstacles, ultimately, he has the authority to close that prison. When President Bush opened Guantánamo on January 11, 2002, he didn’t seek congressional approval; he just did it unilaterally as a president of the United States. President Obama could do the same. He is choosing not to do it. He’s choosing not to take what he believes is a political risk.

But, unfortunately, the cost of that political decision is borne primarily—and I’m not going to say it’s bad for the United States, because I think that gets it wrong—it’s bad primarily for the men who are there, their families, their communities. And ultimately, sure, it is also bad for the United States from a policy perspective, from a legal perspective, from a reputational perspective. But—

AMY GOODMAN: And explain that reputational perspective and the anger that it generates.

RAMZI KASSEM: I mean, it’s—you know, I have friends who worked at the State Department, for example. And when they sat across tables from representatives of other governments with spotty human rights records and tried to lecture them on those human rights records, the immediate retort was, “Well, you guys have Guantánamo.” And that’s a conversation ender, right? And I don’t subscribe to a notion—I don’t idealize sort of the United States’ human rights record by any stretch. I am fully aware of the unfortunate way that our country participates in the world. But this continues to be, you know, a stain on the United States’s reputation. It continues to impede, you know, the spread of equality and dignity worldwide. And it’s a model for other countries. There are mini Guantánamos popping up left and right. And so, for as long as the United States has that facility running, the risk is there.

My concern also with President Obama’s so-called plan to close Guantánamo is that it is not a plan to close Guantánamo. It’s a plan to relocate Guantánamo, to import it to the United States, to close that facility in Cuba, but bring the practice here to the United States, where it will inevitably approved by the courts. And so, to the extent President Clinton, if she is elected, you know, picks that up as her own plan for closing Guantánamo, I think we’re going to have to keep our guard up and continue to call it for what it is, which is not closure, but simply relocation of a practice that the entire world has denounced.

AMY GOODMAN: And if it’s President Trump?

RAMZI KASSEM: And if it’s President Trump, then we know what he’s going to do, or at least what he says he’s going to do, right? Which is far from even closing the facility, expanding it and, you know, further normalizing its use. But I say “further normalizing” because President Obama has already done that damage. For two—for two administrations, for two terms, he has maintained, he has kept Guantánamo open. His Justice Department lawyers have gone into court and made the very same arguments that—and I say this as a lawyer who’s litigating against the Justice Department. The same arguments that the Bush administration lawyers were making in 2008 are the ones that the Obama administration lawyers started making in 2009 and to this day, in 2016. And so, you have to ask yourself: How serious is the White House about closing this prison? And the unfortunate answer is that, no, they’ve caved to political considerations.

AMY GOODMAN: And what would—if you can say this, what would a just closing of Guantánamo look like?

RAMZI KASSEM: It would mean you release the men that you are not going to try. And when I say “try,” I don’t mean a military commission. I have represented a prisoner in front of a military commission. I’ve tried a case almost fully in front of a military commission. I know what that system is. That system is designed to produce convictions, not justice. It is designed to cover up the centrality of torture in all of these cases. Those are the two main purposes of the military commissions. That’s not what I mean when I say “try.” And I’m not idealizing our own criminal justice system. It has very serious imperfections, especially when it comes to defendants of color, especially when it comes to Muslim defendants in so-called terrorism cases. So I’m not glossing that over at all. But I think, fundamentally, closing Guantánamo means, for the men that you have evidence against that is admissible, you try them in a fair court of law—so, not a military commission, a regular court, not a military court. And for the other men, you repatriate them or resettle them as free men. And ideally, you compensate them. You recognize what was done. You don’t wait a generation or two, like with Japanese incarceration, to recognize that people were tortured.

What we’ve seen, unfortunately, is torture tapes being destroyed by the CIA, evidence of forced feedings, tapes, not being publicly disclosed. Mr. Dhiab’s is one instance. I had a case, Ahmed Salim Zuhair, who, when he was released in 2009, was the longest-running hunger striker at Guantánamo at the time. He had been on hunger strike from June 2005 until the day he arrived home in Saudi Arabia in June 2009. We got the judge to order them to hand over tapes of his force-feeding. Those tapes are also classified. They have not been released. And so, there’s all this evidence that’s being kept out of public view for one very simple reason, which is that the United States government knows that there will be an outcry if these things become public.

AMY GOODMAN: The Justice Department says the graphic images will incite violence. So, then, the media organizations say, “Then you’ll make them more and more graphic—I mean, the torture will get worse—simply so that you won’t have to release them.”

RAMZI KASSEM: That’s exactly right. I mean, what conduct does that sort of argument, if it’s accepted by the courts, incentivize? Like, if the courts were to accept that argument, then it would incentivize, it would push the U.S. government, to get more and more extreme in its misconduct—right?—in its mistreatment of civilians, in its torture of prisoners, so that they could then go to court and say, “Wow! This is—this is crazy stuff. I mean, this is horrible. It’s medieval. We really can’t release it, because it makes us look so bad that people may take action.” Unfortunately, yeah, you know, I don’t think that holds water. How else are we going to hold our government to account? How else are we going to, you know, hold them to account for what they are doing in our name, using our taxpayer dollars? I mean, all of this is funded by us, and we don’t know. We barely see the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what the government did in our name at these secret facilities, and continues to do in places like Guantánamo today.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, clearly, it’s a political decision. Do you find, in times like this, in the aftermath of the attacks this past weekend, that it’s more difficult to raise these issues?

RAMZI KASSEM: Look, politicians are always going to try to sort of exploit the moment and instrumentalize moments like this, and so we see that certainly with Lindsey Graham now in the wake of, you know, the Chelsea bombings, saying that that individual, even though he’s a U.S. citizen, should be held as an enemy combatant. And, you know, the only concession that Graham made was that he should be tried in the civilian system ultimately, but initially held as an enemy combatant. Of course, we don’t see Lindsey Graham clamoring for that sort of outcome when a white man walks into a church in Charleston and shoots a number of black congregants. We didn’t see him calling for that individual to be held as an enemy combatant—nor should he. You know, I’m not saying that we should all be equal in that direction. I just think the notion that we should apply this fabrication, the term “enemy combatant”—and when I say “fabrication,” I mean it. As a legal matter, that term didn’t exist before the Bush administration as a matter of international law. So the idea that we should normalize that, you know, further entrench it in our law, apply it to a larger category of individuals, is irresponsible and reckless and destructive.

AMY GOODMAN: You head back there. What is it like at Guantánamo?

RAMZI KASSEM: You know, Guantánamo has changed a lot over the years. Right? So it really depends on when it is. And it hasn’t changed in a linear fashion, right? There are periods when it’s better—the conditions, I mean, for our clients. And there are periods when it’s worse. And so, that’s not predictable. It’s not linear.

For me, you know, as an American, as a lawyer, as an Arab and a Muslim, it’s a deeply unsettling place. You arrive in this—you know, what’s probably the most pristine, untouched, most untouched corner of the Caribbean at this point. There are no touristic developments. It’s stunning. It’s a stunning, beautiful part of the world, scenically. But then you juxtapose that with the symbolic weight of the place. You juxtapose that with the knowledge of what’s been done to human beings in that place, and what it represents fundamentally since 2002. It’s a place that was designed to, you know, dehumanize and break down people. And so—and it’s a very uncomfortable juxtaposition. So, for me, you know, I really—I’m grateful for the time that I get with my clients there and for whatever I can do to help them and their families, but I’m always also happy to be on that plane leaving. So, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Ramzi Kassem, thanks so much for being with us, professor of law at City University of New York School of Law, where he directs the CLEAR project, which stands for Creating Law Enforcement Accountability & Responsibility. This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options