Related

Guests

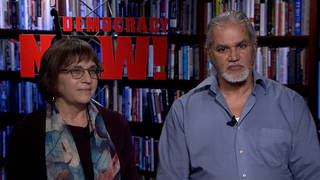

- Arlie Russell Hochschildauthor of Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. The book has been long-listed for the 2016 National Book Award. She is a professor emerita of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Part 2 of our interview with famed sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild. She spent much of the last five years with some of Donald Trump’s biggest supporters, researching her new book, “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right.” It has just been nominated for a National Book Award.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, in the wake of Monday night’s first presidential debate, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has begun lashing out at everyone from moderator Lester Holt to a former Miss Universe beauty pageant winner. Speaking to Fox News on Tuesday, Trump accused Holt of asking, quote, “unfair questions,” unquote. He also reiterated his criticism of former Miss Universe Alicia Machado, whom Clinton had mentioned during Monday night’s debate.

DONALD TRUMP: When she brought up the person that became—you know, I know that person. That person was a Miss Universe person. And she was the worst we ever had. The worst, the absolute worst. She was impossible. And she was a Miss Universe contestant, and ultimately a winner, who they had a tremendously difficult time with as Miss Universe.

STEVE DOOCY: Did not know that story.

BRIAN KILMEADE: Well, I didn’t know either.

ELISABETH HASSELBECK: What—

DONALD TRUMP: She was a—she was the winner, and, you know, she gained a massive amount of weight, and it was—it was a real problem. We had a—we had a real problem.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Donald Trump speaking on Fox & Friends Tuesday morning. They didn’t ask about him; he raised this story unsolicited, after being asked if Hillary Clinton had gotten under his skin. And this has launched a tremendous response. Alicia Machado has done an interview with The Guardian. She was from Venezuela. Donald Trump, at the time that he says his Miss Universe gained weight, brought cameras into the gym to show her exercising.

Well, we’re going to Part 2 of our conversation with the renowned sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild, who traveled deep into Louisiana’s—into Louisiana, the bayou country, a stronghold of the conservative right, to better understand Trump supporters. Arlie Hochschild is author of the new book Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, which has just been long-listed for the 2016 National Book Award. She’s a professor emerita of sociology at the University of California.

Thanks for staying with us, Arlie. We want to go to this example of Alicia Machado, because clearly he is pounding on this young, vulnerable woman, who says she had a eating disorder for years as a result of what he did to her.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And I wanted to go to this issue of attacking the vulnerable.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: And how does this fit into people’s attraction to Donald Trump who you spoke to in Louisiana?

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Wonderful. Because they actually feel vulnerable. It’s a—that’s a paradox within a paradox. I think they relate to his dominance, you know, his—and even in the presidential debate, he began edging out, interrupting, taking more space. He actually said more words, I believe, in that debate than Hillary did.

AMY GOODMAN: Interrupted Hillary Clinton like 29 times.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Twenty-nine times. So, what is that? And would that—would he be seen as unmannerly and boorish, or, you know, a guy who takes charge, a guy who dominates? I think, actually, people relate to that dominance, that that’s a plus for them. And yet, you know, when he’s—he does—you could do a choreography of shame, who—he just shames people. He shames the reporter who had a disability. He shames Alicia with her eating disorder. He shames women. He shames, tacitly, blacks and immigrants, even, you know, the children of immigrants—everybody except white, blue-color men. And you can sort of do a little shame picture. And in a way, he’s trying to reverse, I think, what they feel has happened to them, that they feel like a new minority group that doesn’t dare say, “Hey, we’re a minority group, and we’re getting stepped on, and we deserve attention.” They don’t dare say it because of the bravado, sort of what I call a deep story self. But they feel that vulnerability, and he seems to be pushing back and making everybody else vulnerable but them. I think that’s the tacit appeal here.

AMY GOODMAN: Did anyone in Louisiana who you talked to, in this very conservative swath, raise doubts about Donald Trump?

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Yes, they all did. It’s like nearly all of them came to him reluctantly. They didn’t say, “Oh, yeah, that’s our guy.” One very wonderful couple, that I’ve actually dedicated the book to, suffered greatly from environmental pollution. They said, “When he imitated the disabled man, you know, no, that’s an immoral thing. He couldn’t be a good person.” Another said, “Woah, he’s going to create an enormous state, great big debt. How are you going to catch every undocumented worker without setting up a giant surveillance state that’s going to cost an arm and a leg? We’re tea party forgetting.” So they had that objection. So, it’s that they didn’t feel spoken to by the Democratic Party. The party of the working man turns out to have pushed away the working people that it, you know, was supposed to attract.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: You also talk in your book about the historical legacy of the culture of Louisiana, that the—the legacy of the plantation society in the 1860s and then of the movements of the 1960s and how that has affected the psyche that’s been handed down for—over generations, for how people look at the world. Can you talk about that, as well?

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Yes, that’s right. In a way, the plantation system set up a tiny elite, a great big traumatized bottom of slaves, planters’ slaves, and really not much in the middle. So, that was kind of the normal thing. And there was no public sphere, you know, of government services for everybody. That didn’t exist. And if you look at the history of poor whites in the plantation system, they were shoved aside. The best land was taken by the plantation owners. So the poor whites ended up in the swamps and hinterlands, and even the forest took game away from their dinner table, and their labor wasn’t needed, because the planters had slaves. So, they were marginalized, and yet the planters appealed to the poor whites and tried to forge an alliance—you know, we whites together.

And, in essence, the oil companies and the petrochemical companies, historians have said, are the new plantation. And again, it seems like you don’t need a middle class, you don’t need a public sector that is available to everyone. And so, I think, actually, many people, in the back of their mind, think of the federal government as the North, wagging its moral finger, telling us what to do. And they have this model of the plantation, so that where is good government in that model?

And then come the '60s, as you say, where all these other groups come up to fill the middle class, and they seem like they're getting ahead. I many times heard, “Oh, all the poor mes”—you know, black poor mes, women poor mes, immigrant poor mes, you know? And we’re tough. We’re stoical. We haven’t said, “Poor me.” But they find themselves in a contradiction now. They’re facing contradiction because, in their heart of hearts, they feel like poor mes, and yet they feel too proud to say it.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to a clip of Donald Trump being questioned by Jake Tapper on CNN about David Duke.

DONALD TRUMP: Well, just so you understand, I don’t know anything about David Duke. OK? I don’t know anything about what you’re even talking about with white supremacy or white supremacists. So, I don’t know. I mean, I don’t know—did he endorse me, or what’s going on, because, you know, I know nothing about David Duke. I know nothing about white supremacists. And so, when you’re asking me a question, that I’m supposed to be talking about people that I know nothing about.

JAKE TAPPER: But I guess the question from the Anti-Defamation League is—even if you don’t know about their endorsement, there are these groups and individuals endorsing you. Would you just say, unequivocally, you condemn them, and you don’t want their support?

DONALD TRUMP: Well, I have to look at the group. I mean, I don’t know what group you’re talking about. You wouldn’t want me to condemn a group that I know nothing about. I’d have to look. If you would send me a list of the groups, I will do research on them, and certainly I would disavow if I thought there was something wrong.

JAKE TAPPER: The Ku Klux Klan?

DONALD TRUMP: But you may have groups in there that are totally fine, and it would be very unfair. So give me a list of the groups, and I’ll let you know.

JAKE TAPPER: OK, I mean, I’m just talking about David Duke and the Ku Klux Klan here, but…

DONALD TRUMP: I don’t know any—honestly, I don’t know David Duke. I don’t believe I’ve ever met him.

AMY GOODMAN: So that was—that was Donald Trump being questioned by Jake Tapper on CNN about David Duke, of course, a son of Louisiana—

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —who has endorsed Donald Trump. And Donald Trump’s having trouble, though he eventually disavowed support, it came under enormous pressure. Talk about David Duke, Donald Trump and the people you spoke with.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Yeah, yeah. The way Trump disavowed Duke says everything. He said, “I disavow, OK?” That’s how he said it, as if “I’m being forced to,” wink-wink, to people that understand that the liberals have pressed him to this position. I thought that was actually, from his point of view, very canny kind of winking. So, how—I think this is his covert way of appealing to people who are blaming blacks for their problems.

AMY GOODMAN: Does David Duke have an appeal to the people that you spoke with?

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: No, actually not. They say, “Well, he’s racist.”

AMY GOODMAN: The former Klan leader.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: The former Klan leader, they disavow. And that was their saying to me: “Look, I’m—I don’t hate blacks. I don’t use the N-word. I’m not a racist. And we don’t need David Duke. No.” So, Hillary is wrong to say “deplorable” for half of Trump’s—she’s given up on them. I haven’t. I think what I’m looking at is all of the crossover issues that are possible. And one of them actually is, paradoxically, I think, coming to terms with the race issue.

So, for example, I just gave a reading in New Orleans, and this guy, Mike Schaff, who I interviewed and profiled in the book, was in the audience. And I’m reading about him to him—wasn’t a great talk, but I—because I—and he’s listening and is moved, actually, by that reading. Later, a professor of African-American studies asked me, “Well, how does race play into this?” And I begin a kind of—to go into that, answer that question. Later, Mike comes up with this woman, whose name is Nikki, begin talking and agree to meet to continue the conversation. And we need more of that. I think it can happen. And people feel insulted to be called racist, but they don’t understand racism in a structural way.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But I think one of the telling moments, to me, in—as you’re talking about race, is the—in Monday night’s debate, was when Trump referred to President Obama at one point as “your president.”

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Yes, yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And said to myself, “Wait a second. 'Your president'? If any president has tried to be a president for the entire people, I’d say you’d have to say it’s President Obama.” But yet—and I’m wondering, when you interviewed folks in Louisiana, did they feel that way, that this was—this was a president of someone else, not of them?

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Yes. Yes, they did. That’s part of the deep story. It’s how it felt to them. “He’s sponsoring people unlike me. He’s pushing me back in line. He’s not waving to me. He’s not saying, 'Oh, you, too.'” And so, they did feel—that’s how they’ve came to feel stangers in their own land. And I felt as you do: “But isn’t he trying to reach across? If anybody has, he has.” But they didn’t experience it that way.

AMY GOODMAN: And your subtitle, Anger and Mourning on the American Right, why “mourning”?

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: We see the anger, but we don’t see the mourning. I think these people are in mourning for a lost way of life, for a lost identity. This man has lost his community, his home, so even the air isn’t his. It belongs to the petrochemical plants. And the water isn’t.

AMY GOODMAN: Who he doesn’t blame.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: And who he doesn’t blame. Although when I put it to him that the companies were taking tax money and giving gifts so as to cultivate gratitude, and that—forcing the state to be the bad guy, and that’s why he hated the state, he nodded his head yes. So not only are there crossover issues, there’s crossover thinking. If you—if you have two beers and you go fishing for a while, it’s not that you agree on everything. And this book isn’t saying that we can, but it’s saying we can find common ground on certain issues and start there, and that a lot of people who think liberals are the enemy, and are insulting them and calling them reprehensible, are actually agreeing on a lot of things. A lot of people I talked to love Bernie Sanders. They said, “Oh, Uncle Bernie. Oh, well, he’s pie-in-the-sky socialist, but good ol’ Uncle Bernie.” It’s Hillary they couldn’t—didn’t feel represented by. So, there are possibilities—that’s what I’m saying—long-term possibilities, that I think the shoe is on our foot to reach across.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much, Arlie, for joining us.

ARLIE RUSSELL HOCHSCHILD: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. Again, the book has been listed for the 2016 National Book Award. Arlie Hochschild is professor emerita of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Go to democracynow.org to see Part 1 of this conversation. Thanks so much.

Media Options