Related

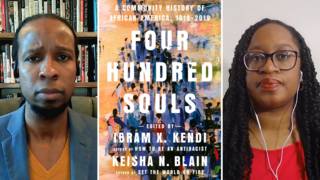

As Republican lawmakers attempt to make it harder to vote in states across the country, we look at the life and legacy of Fannie Lou Hamer, the civil rights pioneer who helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Historian Keisha Blain writes about Hamer in her new book, “Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America.” In addition to fighting for voting rights, Hamer challenged state-sanctioned violence and medical racism that Black women faced. Blain based the book’s title on a frequent saying of Fannie Lou Hamer’s: “Whether you are Black or white, you are not free until I am free.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Fannie Lou Hamer, singing with other civil rights activists “This Little Light of Mine.” This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, as we end today’s show looking at the fight over voting.

A new report by the Brennan Center has found 19 states have enacted 33 laws to make it harder for people to vote. Earlier this week, People for the American Way President Ben Jealous and four others were arrested outside the White House. They were calling on the Senate to remove the filibuster as an obstacle in passing voting rights.

We turn now to look at a pioneering woman in the struggle to guarantee voting rights: Fannie Lou Hamer. She’s the subject of a new book by the acclaimed historian Keisha Blain. Fannie Lou Hamer was the daughter of Mississippi sharecroppers, who became involved in the civil rights movement when she volunteered to attempt to register to vote in 1962. By then, the 45-year-old mother lost her job and continuously risked her life over her civil rights activism.

Despite this and a brutal beating, Fannie Lou Hamer helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the white domination of the Mississippi Democratic Party. In 1964, the party challenged the all-white Mississippi delegation at the Democratic National Convention, with Fannie Lou Hamer as the leader. Her voice, along with others, led to an integrated Mississippi delegation in 1968. This is part of her address at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on August 22nd, 1964, where she testified before the Credentials Committee about her efforts to register to vote.

FANNIE LOU HAMER: It was the 31st of August in 1962 that 18 of us traveled 26 miles to the country courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens. We was met in Indianola by policemen, highway patrolmen, and they only allowed two of us in to take the literacy test at the time. After we had taken this test and started back to Ruleville, we was held up by the city police and the state highway patrolmen and carried back to Indianola, where the bus driver was charged that day with driving a bus the wrong color.

After we paid the fine among us, we continued on to Ruleville, and Reverend Jeff Sunny carried me four miles in the rural area, where I had worked as a timekeeper and sharecropper for 18 years. I was met there by my children. They told me the plantation owner was angry because I had gone down, tried to register. After they told me, my husband came and said the plantation owner was raising Cain because I had tried to register. And before he quit talking, the plantation owner came and said, “Fannie Lou, do you know — did Pap tell you what I said?”

And I said, “Yes, sir.”

He said, “Well, I mean that.” Said, “If you don’t go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave.” Said, “Then, if you go down and withdraw, then you still might have to go, because we are not ready for that in Mississippi.”

And I addressed him and told him, said, “I didn’t try to register for you. I tried to register for myself.”

I had to leave that same night.

On the 10th of September, 1962, 16 bullets were fired into the home of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Tucker for me. That same night, two girls were shot in Ruleville, Mississippi. Also, Mr. Joe McDonald’s house was shot in. …

If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hook because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings in America?

AMY GOODMAN: That was Fannie Lou Hamer’s address at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City in ’64.

For more, we’re joined by Keisha Blain, award-winning historian, author of the new book, Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America.

Professor Blain, welcome back to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us.

KEISHA BLAIN: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about that moment in time and why you have decided to write a book on Fannie Lou Hamer.

KEISHA BLAIN: Well, this particular moment, I think, is the most well-known moment in Hamer’s life. I think anyone who knows anything about Fannie Lou Hamer know her in the context of the 1964 Democratic National Convention. And as everyone has already heard, she spoke so passionately about Black voting rights, shared her painful experiences organizing in Mississippi.

And I think, for me, certainly, over the last couple of months, and I would say over the last couple of years, I’ve been thinking deeply about Fannie Lou Hamer, certainly her fight for voting rights, but more sort of thinking about her political strategies, thinking about her ideas and how they might be applicable to addressing a number of social problems, which, of course, we are still dealing with, including voter suppression. So I wanted to write a book that would help connect the dots and be a useful educational tool for many.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the trajectory of Fannie Lou Hamer’s life.

KEISHA BLAIN: Well, one of the things that I explain in the book is that she came to the civil rights movement fairly late in life. She joined the movement in August 1962 at the age of 44. But one of the things that I think also is important in thinking about how her activism developed is a painful experience that she endured a year before she joined the civil rights movement, and that is in 1961. She was the victim of a forced sterilization. And, of course, that is fitting in light of our conversation already about Henrietta Lacks.

And Fannie Lou Hamer went through this painful experience in ’61, which, initially, she did not talk about publicly. But when she became a civil rights activist in ’62, one of the things that she did was she spoke out about state-sanctioned violence, not only talking about police brutality, police violence, but also talking about medical violence, talking about how white physicians in Mississippi, across the South, would perform this terrible practice of forced sterilizations. And so, Hamer became a voice not only for civil rights, but also, I think, broadly, for human rights.

AMY GOODMAN: She spoke out painfully about her own experiences. In this recording, Fannie Lou Hamer recounts her beating at the hands of two other Black prisoners on the orders of her white jailers in Mississippi, after she traveled to a distant courthouse to take the state’s required literacy test to vote. The recording is from the Pacifica Radio Archive, which has one of the largest archives of Fannie Lou Hamer recordings.

FANNIE LOU HAMER: Then three white men came to my cell, and one of them was a state highway patrolman, because he was wearing a little silver plate across his pocket that said “John L. Basinger.” And he asked me where I was from, and I told him I was from Ruleville. And he said, “I’m going to check that.” And he went out. And I guess he called Ruleville, and they didn’t like me in Ruleville because I worked with voter registration there. And when he came back, he said, “You’re damn right. They say you’re from Ruleville, all right. And we going to make you wish you was dead.”

And they led me out of that cell into another cell. And he gave a Negro prisoner a blackjack, and he ordered me to lay down on a bunk bed. And the Negro prisoner said, “Do you want me to beat her with this, sir?”

And he said, “You’re damn right, because if you don’t, you know what I’ll do for you.”

And I laid down on the bunk like he ordered me to do. And the first Negro beat me. He beat me until he was exhausted. And after he beat, the state highway patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack. And during the time he was beating, I began to work my feet, because that was a horrible experience. And the state highway patrolman ordered the first Negro that had beat to set on my feet, while the second one beat me. And I just began to scream, where I couldn’t control it. And then the white man got up and began to beat me on my head.

I have a blood clot now in the artery to the left eye and a permanent kidney injury on the right side from that beating. These are the things that we go through in the state of Mississippi just trying to be treated like a human being.

AMY GOODMAN: “Just trying to be treated like a human being.” Those are the words of Fannie Lou Hamer, preserved by the Pacifica Radio Archive. It is utterly painful, decades later, to hear this description, but also the vibrancy of Fannie Lou Hamer. What is most misunderstood about her, Professor Blain?

KEISHA BLAIN: Well, I think so many people who know about Fannie Lou Hamer will know her in the context of the American civil rights movement. Of course, we’re talking about the key role she played in expanding Black political rights. But I think, in the process of writing the book, one of the things that really stayed with me is how much we have to think about Hamer and talk about her as a human rights activist. And this is something that she said. You know, she said that, yes, she was certainly fighting for civil rights, but she was fighting for human rights broadly. And Hamer connected the struggle of Black people in the United States with the struggle for liberation across the globe. And this was something that I think, you know, I certainly hope, in reading the book, that people will come to appreciate, to think about her internationalist perspective. That, I think, is so vital in understanding her legacy.

AMY GOODMAN: Black women have been so central to so many human rights struggles around the world — anti-colonial, Black freedom, human rights — but aren’t seen as being that central. Talk about the centrality of Black women, like Fannie Lou Hamer, when it comes to pushing for democracy here and around the world.

KEISHA BLAIN: Black women have been vital to the struggle for human rights for decades, for centuries. And as you point out, I think so many times when we tell these narratives, mainstream narratives tend to focus on the political work of men. So, we still have male-dominated narratives. We also have these masculinist narratives, you know, ones that do not pay attention to the way that Black women not only led but really strategized. You know, they were activists as well as thinkers. They were producers of knowledge. And I think Fannie Lou Hamer’s story is an important reminder of the centrality of Black women in shaping political movements. Even when they are marginalized in the broader narratives, their work has certainly remained vital. And to this very day, we’re talking about Hamer. She has left a remarkable legacy.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about your choice of the title, Until I Am Free.

KEISHA BLAIN: Until I Am Free comes from a phrase that Hamer said repeatedly as she traveled across the United States in the late '60s and also the ’70s. She would say that “Whether you are Black or white, you are not free until I am free.” And this is a message that I think we have to remember today. All of us, despite our differences, regardless of our racial background, regardless of our ethnicity, regardless of our sexuality, our socioeconomic status, we are all members of this American polity. And I think Hamer's phrase was an important reminder that because we are all connected, we have to work together to ensure that we build this nation to become an inclusive democracy, that we certainly said it should be, according to the values stated in the Constitution.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you so much for being with us, Keisha Blain, author of Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America. Professor Blain teaches history at the University of Pittsburgh.

That does it for our show. Democracy Now! is currently accepting applications for two full-time positions: a director of finance and administration and a human resources manager. You can learn more and apply at democracynow.org.

Democracy Now! is produced with Renée Feltz, Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud and Adriano Contreras. Our general manager is Julie Crosby. Special thanks to Becca Staley, Miriam Barnard, Paul Powell, Mike DiFilippo, Miguel Nogueira, Denis Moynihan, Hugh Gran. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options