Related

Guests

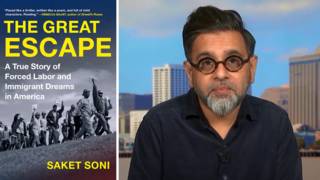

- Isabel Allendebest-selling Chilean American writer and one of Latin America’s most renowned novelists. Her latest book is called The Wind Knows My Name.

In an in-depth interview about her work, we speak with Isabel Allende, one of the world’s most celebrated novelists, author of 26 books that have sold more than 77 million copies and have been translated into 42 languages. Her books include The House of the Spirits, Paula and Daughter of Fortune, and her latest novel is The Wind Knows My Name, which looks at the trauma of child-family separation, from Nazi Germany to the U.S.-Mexico border, and those on the frontlines helping migrant children. “That idea of separating the kids is extremely cruel, but it keeps happening,” Allende tells Democracy Now! The Chilean American author says the “miracle of literature” is being able to instill compassion in readers who may otherwise see the stories of refugees as abstract numbers. “It brings people close. By telling the story of one child, you can somehow connect with the reader and create that sense of empathy that is so often lacking.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We spend the rest of the hour with Isabel Allende, one of the world’s most celebrated novelists, the author of 26 books that have sold more than 77 million copies and been translated into more than 40 languages.

Isabel Allende was born in Peru in 1942. She traveled the world as the daughter of a Chilean diplomat. Her father’s first cousin was former Chilean President Salvador Allende. This September marks 50 years since Augusto Pinochet seized power from Allende in a CIA-backed military coup — the date, September 11, 1973. Salvador Allende died in the palace that day. Isabel Allende would later flee from her native Chile to Venezuela.

Her books include The House of the Spirits, Paula and Daughter of Fortune. Her latest novel, The Wind Knows My Name, looks at the trauma of child-family separation, from the Nazi Holocaust to the U.S.-Mexican border, and those on the frontlines helping migrant children.

On Thursday, I interviewed Isabel from her home in California. I asked her to start by telling us the story of her new novel, The Wind Knows My Name, beginning in 1938.

ISABEL ALLENDE: In 1938, in November, it was the Kristallnacht in Germany and Austria. And it was a night in which the Nazi mobs attacked the Jewish houses and establishments, commercial establishments, and they broke the windows and beat up people. And it was just a very scary and terrible preamble to what was going to happen very soon after. And at that point, the Jewish community realized that they had to get out, so many people started looking for visas and places to go. England offered 10,000 temporary visas for children, to get the children out. So, many families had the terrible choice of sending their children away to save them from a potential danger that was there in the air. And they knew it was coming, but they couldn’t be very sure. And still they had to make that choice.

So, these kids, ages — I don’t know — 1 year old up to 15, went in convoys, in trains, to the Netherlands and other places, where they would be sent to England. They were received by people who offered their homes, also by orphanages and other establishments, but, really, the parents never knew who was going to receive the kids or what was going to happen to them. Most of them, more than 90% of them, never saw their families again. That separation, that was supposed to be temporary, became permanent. And those children, who lost everything, were raised in other places. They had a life in England or in Europe, or they came to the United States. Many of them became very successful. But I heard on television some interviews to very old people who were part of the Kindertransport, and they had a hole in their heart. They never forgot the trauma. They lived with that all their lives.

So, when the separation of families at the border here happened in 2017 and '18, I remembered the Kindertransport and other instances in which the children have been taken away from the parents. For example, during slavery, children were sold out to — taken from their mothers' arms. In many Indigenous tribes, not only in the United States, but in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, in many places, the children were taken away to put them in some Christian orphanages, horrible places where many of them died of abuse and starvation. So, that idea of separating the kids is extremely cruel, but it keeps happening.

And that prompted me to write the book. I was already thinking about it, when I had — I saw a case, through my foundation, that really triggered the writing. And that was the case of a little girl with her brother. She was 7, and the brother — she was almost 7, and the brother was 4. And they came with their mother to the United States illegally. They were separated at the border. The mother was detained, arrested and sent away. And the children were in detention centers and then in foster homes and whatever. The problem is, the girl was blind. And can you imagine a little blind girl was in charge of her brother and who doesn’t know where she is, doesn’t speak the language, can’t see, can’t even recognize people or places? So, that, the terror of that girl, was what triggered the book.

But then I realized that, like in most of my books, I don’t focus on the victims as much as on the people who are trying to help, because it is through them, through their actions and through their eyes, that I can tell the story without plunging into the depth of hell.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go back for a moment to the Kindertransport that you talk about. We dug up a documentary called Kindertransport, directed by Fran Robertson and Kevin Macdonald. In this clip, we hear Leo Metzstein and Edith Forrester.

EDITH FORRESTER: In the evening, my mother took me to the railway station. And then I really felt, for the first time, that there was going to be something terrible happen. And I remember saying to my mother, “You’re coming, too.” And she said, “Well, no, not just now. I hope to come later.”

LEO METZSTEIN: The station was a horrific experience. I mean, you can just imagine, with thousands of people there, and they were letting their children go. And it was just horrible to see. I just looked back to see my mother and sister standing there. That’s the worst memory I’ve got. And I’m just crying all the time, just crying, crying, crying. That’s all I could do.

EDITH FORRESTER: And then, as the train just lurched a little, I screamed. I can hear my voice yet, shouting, “Mutti! Mutti! Mommy! Mommy!” And somebody lifted me up, and I was able to see, over somebody’s head, my mother’s face, her eyes frantically looking for me. And that was my last sight of my mother.

AMY GOODMAN: Those voices from the documentary Kindertransport. And that’s the story you tell, of a young Samuel, who, too, would never see his parents again, Isabel.

ISABEL ALLENDE: Yeah. It was very easy for me to put myself in the place of Samuel. I really felt his pain. And Samuel, for me, is a very interesting character, because this is a man who, because of the trauma of his childhood — he was really a musical prodigy, but that was lost in the shuffle and the war and everything else — he tries to have a very safe life. So, he becomes a musician in the symphony. He has a sheltered life, a protected life, in which he doesn’t want to get involved in anything that will upset him. He’s married to a wonderful, extravagant woman, and he doesn’t know about her infidelities or about her secret activities or who she’s — what she’s doing and with whom, because that would upset him. He just wants everything as nice as possible.

And then the pandemic hits when he’s 86, and he finds himself at home, sheltering at home. The terror of being alone, he asks his housekeeper, Leticia, to please stay with him, thinking it would be just for a week or two. And so they start living together. And then, at 86, he can reflect about his life. And there’s a point when he says, “I wasted my life. I let life pass by, and I didn’t participate in anything. I am guilty of the sin of indifference. And sooner or later in life, you pay for that.” And then life gives him the opportunity to atone for that sin of indifference, when he opens his heart and his house and his life to the little girl that knocks at his door, this little blind girl.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, as I was reading about Anita, the little girl, I couldn’t help but think back to 2018 inside that U.S. Customs and Border Protection facility in which children are heard crying “Mama” and “Papi” after being separated from their parents, the kids believed to have been between the ages of 4 and 10 years old. I want to play that clip for a moment.

CHILDREN: [crying] Papi! Mommy! Papi! Papi! Papi! Papi!

AMY GOODMAN: That audio shocked the world, was later played by reporters at a White House press briefing, also blasted from speakers to donors as they arrived at a Republican fundraiser at Trump’s hotel in Washington, D.C., these children separated under Trump’s child separation policy, what, still hundreds, if not a thousand or more, still never reconnected with their families, with their parents. Talk more about Anita and her journey.

ISABEL ALLENDE: Well, in the case of the real Anita, the girl who inspired the book, she couldn’t hear where her mother was or reunite with her mother, but there were lawyers and social workers trying to put the family together again. Eventually, after eight months, they were reunited. And they went in front of a judge, who deported them all. And they were deported to Mexico, where we never heard from them again. So, it’s a very tragic story, one of the many tragic stories. But there are still, as you said, a thousand kids, at least, that have not been reunited, because no one thought about it. They thought about the separation, not the unification, the reunification.

So, there are many, many aspects of this that are terrible. For example, the name of the book, The Wind Knows My Name, the idea is that in order to keep track of the kids, they give them a number. Sometimes the kids are so little, they are babies. They don’t even speak English. They don’t know — they don’t speak anything, or they are so traumatized that they won’t speak. So, even their names are lost, and they become numbers.

So, when we think of refugees — and there are 170 million refugees in the world — we think of numbers. That doesn’t mean anything. We need to see the face, hear the story, know the name, so that it makes sense. We could be that person. That could be our child. And that is, I think, the miracle of literature, that it brings people close. By telling the story of one child, you can somehow connect with the reader and create that sense of empathy that is so often lacking.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Isabel, so often the power of your books, it’s the stories of real people, but also the way you expand and bend and wind them through your imagination. You tell us the story of Anita and also Leticia. And if you could tell us her story and talk about what happened in El Salvador in 1981?

ISABEL ALLENDE: Well, the thing is that when we think of migrants and refugees, why are they coming? There’s a moment in the book when someone — when the lawyer, Frank, says, “Well, if they know that they’re going to take the children away, why are they coming?” Well, they come because they’re desperate. They’re running away from extreme violence in their countries or extreme poverty. And so, taking the chance of crossing the border is preferable than staying.

In the case of Leticia, Leticia the housekeeper, she has lived in the United States for many, many years. This is also based on a case, on a very good friend of mine who is from El Salvador, and I see her almost every day because we walk the dogs together. So she helped me a lot with the research for that part of the book. And in El Salvador, there was horrific military repression, in the ’80s especially, and one known massacre was the massacre of El Mozote. And this was, the military entered the zone called El Mozote, which is just farmers, just people who lived off the land. And there were little small villages scattered here and there. And Leticia was one of the children in El Mozote. And she had a stomach problem, and she was taken by the father to a hospital in the city, and so she was not there when the massacre happened.

So, the military came in trucks and helicopters, and they took over the village — not only that village, several — and they separated the men from the women. They tortured everybody, including the children. They killed everybody, including the pets. The children were inside what was supposed to be a little chapel or something, and they burned the whole thing to ashes. And then, three days later, after this orgy of blood and cruelty and death, they left the place.

And the government covered the whole thing up for years and years. Some people who presented this horror story, because this military were trained by the CIA in Washington, and it was also covered by the press there and by the government. So, for more than 10 years, the whole story was kept silent. And there’s a thousand people dead there. And this is in a very small country. So, I needed to talk about El Mozote to explain why people get out, why people have to escape. What you do if you have to confront the maras, the gangs, the narcos and the military? So, it was necessary for me to tell the story of Leticia, as well, to understand why people immigrate.

AMY GOODMAN: The story of El Mozote is so horrifying, and you depict it so unforgettably in The Wind Knows My Name. In El Mozote, the Atlácatl brigade, that was trained, as you said, by the United States. Tell us more about The Wind Knows My Name, that title, and how you continue at the age of 80. You cannot be without a pen, or maybe it’s a computer. Are you using a pen for the first draft or a computer these days?

ISABEL ALLENDE: No, I don’t have a draft. I start all my books on January 8th out of discipline, and superstition, probably, too. And then I sit in front of the empty blank screen, and often I don’t even know what I’m going to write about. I have a vague idea. If it’s a historical novel, I might have researched the place and the time. But I confront the screen at the beginning with an open mind. I don’t know what’s going to happen, really. And I don’t have a draft. I don’t have a script.

Things happen. And somehow, it seems — this is a cliché, of course — that the universe conspires to help, because, as I write, it seems that all my antennae are directed out there to pick up the collective unconscious, the collective fears and dreams and the past and memory. And all that I can do, because my work is very silent, and it’s always — I’m always alone. You know, we live in the noise. So, nothing happens in the noise, Amy. When you are in silence in a room with your characters and with your story, things happen. Miracles happen. Ghosts appear. Everything.

AMY GOODMAN: What is the ceremony you perform before you put that — before you start writing on January 8th?

ISABEL ALLENDE: Well, the day before, I clean up. And by “cleaning up,” I mean I take out everything that had to do with the previous book, all the research, the books, the notes, everything. I burn sage. I have my candle, always a new candle. I have my cup of Marco Polo tea ready.

And then I do a little meditation to sort of call in what other people would call inspiration and I call my spirits, the memory of my mother and my grandparents and my daughter, and even the pets that have gone to the other world. I call them in, and I say, “Come on. You have to help me in this process.” And then I feel accompanied and strong.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you have your mother, and then you have your memory of Paula, your daughter, your oldest child —

ISABEL ALLENDE: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — who died, who you wrote a book about, and we’ve talked about that book in the past. But your daughter also the inspiration for your foundation, that works along the border. Talk about Paula and how she influences what you do.

ISABEL ALLENDE: Paula — I think that every parent thinks that their children are special, are different, are extraordinary. And that’s how I remember my daughter. She was a psychologist and a teacher, and she worked always as a volunteer among the poorest of the poor. She never earned any money. So I supported her, with the idea that she would do the good work, and I would go to heaven. So, we had this deal.

When she died, I mean, her premature death really broke my heart. And when I wrote the book Paula, I didn’t want to touch any of the income that would come from that book, of course. It belonged to her. But I didn’t know what to do with it. And eventually, I came up with the idea of creating a foundation to prolong the work that she had been doing. And so, she always worked with women and children, because what she told me, very early on, even before this was common knowledge, was that if you change a woman’s life, you change the family. And if you change and improve the conditions of a family or many families, then the community emerges, and, eventually, a country. And the places that are most backward and poorest in the world are where women are put down the most.

So, that idea that Paula had — very young, she had already come up with that — I decided that that was going to be the mantra of my foundation. So, we work — well, I didn’t know how to do it. Just sending checks here and there didn’t do any good, I think. But then my daughter-in-law walked into our lives, Lore Ibarra, and she took over. And she transformed the foundation. Right now she’s in Africa visiting two of our projects over there. She’s all the time traveling, all the time in touch with our grantees. And she has done a fantastic, fantastic job.

You know, Amy, sometimes I say to Lori, “Lori, what’s the point? This is a drop of water in an ocean, a desert of need. What are we — what does it mean?” And she says, “Don’t think in numbers. Think in lives. If you can improve someone’s life, you’ve done enough. So, let’s think about that: lives.” And I understand that, because I think in stories. And stories are always about people, one person at a time. So that’s what I try to do in my writing, and that’s what Lori does in the foundation.

AMY GOODMAN: You dedicate the book to Lori. And for people who don’t know, Paula, your daughter, died of porphyria, a rare disease, genetic disease?

ISABEL ALLENDE: Yeah, it’s a genetic condition that runs in the family, my former husband’s — I mean, Paula’s father’s family. And two of my granddaughters also have it, and my son. But it doesn’t manifest in males, only or mostly in females, you know, women. So, Paula had an attack. And it shouldn’t be fatal if it’s treated properly and in time. But she was in Madrid. There was serious neglect, I mean, criminal neglect, in the hospital. And Paula ended up with severe brain damage. They tried to hide it. And for five months, they told me that she was going to recover, which, of course, she couldn’t.

And eventually, I brought her, in a coma, all the way from Madrid to California in a commercial United flight. How did I do that? I have no idea. I don’t know. It was, of course, before 9/11, so that that was maybe possible. Today it would be impossible. And I took care of her at home until she died. She was 29 when she died. Now both my granddaughters are older than she was when she died. It’s interesting how life goes by.

AMY GOODMAN: And they both have it, but it is not a fatal condition.

ISABEL ALLENDE: No. One of my granddaughters has had six attacks, serious attacks, and she has survived, and she’s doing well. And now, finally, recently, there is a preventive drug that she is using. Once a month, she gets a shot, and that prevents the attack, or at least it makes it much milder.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk to women, writers, women who are taking care of so many, being able to isolate, as you do, to be able to write, to be able to find that silence? What do you recommend, Isabel?

ISABEL ALLENDE: Well, it’s so hard. Virginia Woolf already said you need a room of your own. And that room doesn’t have to be a physical room. It has to be a room inside you, where you retreat to be alone with yourself and your writing. But that is almost impossible if you have small children. I could not write until my children were teenagers, I mean, older teenagers, so that I could — they already had their lives. Paula was driving. It was a completely different life. I worked at the time in administering a school, 12 hours a day, because I had two shifts. But I could come home, and I didn’t have to take care of the kids. And I knew while I was working that the kids were doing fine. And I also had help at home. I didn’t have to clean up.

And so I could write at night, at the beginning in the kitchen, on the kitchen counter, alone at night and during the weekends. I could find little moments to write. Then I emptied a closet, and I put a board across the closet with a lightbulb on top, my typewriter there. And then I could close the doors of the closet, and my writing was there intact, waiting for me for the next day or another moment to go back to it. But before, when I was writing in the kitchen, that was not possible. I had a canvas bag where I would put everything and carried around with me like a newborn baby. I would never part from that canvas bag until the manuscript was finished. So there’s always ways that one can find for oneself, but it depends very much on your domestic situation.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, you wrote your first book, House of the Spirits, at what? At the age of 40?

ISABEL ALLENDE: Yeah. I couldn’t do it before.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you remind us how you wrote this book? It’s not as if you had an agent. It’s not as if you had a community of writers, as you’re describing. Talk about what inspired you. You were not in Chile at the time, remembering your grandfather’s house.

ISABEL ALLENDE: No, no, no, I was living in exile in Venezuela. We still had the military coup in Chile, the dictatorship, because this was in 1981. It was actually one of the worst times of the dictatorship. So I was living in Venezuela with my kids and my husband, but my husband wasn’t living with us. He was working in another province in Venezuela.

And I heard that my grandfather was dying in Chile, and I started a letter for him. Somehow, I sort of knew that he would not be able to read the letter, because it was his last days, and the mail would take maybe a couple of weeks, a week at least. So, I started a letter, and I wanted somehow to tell him, or tell myself, that I remembered everything that he had ever told me, all the anecdotes of the family, my ancestors, my crazy family. I remembered everything he had told me.

And so I started telling about my great-aunt Rosa, who was my grandfather’s first fiancée, and she died mysteriously before they could get married. Many years later, my grandfather married the youngest daughter in the same family, my grandmother, who was clairvoyant and crazy also, wonderful — a lunatic. And so, I started telling about Rosa, and then something happened. It was like everything I had inside just was poured out in those pages.

I had a little typewriter. And then, at the time, there was, of course, no computers; in order to have a copy of something, you would have a carbon paper behind. But I didn’t have even the carbon paper. It was just one only page with a story. Cut and paste, you would cut with scissors, paste with Scotch tape. So that was how you corrected things. You had to think very carefully, every sentence, because erasing it was almost impossible. You had to start the page again.

So, it was a wonderful process, with such innocence, not knowing anything about the book industry. I had never read a book review in my life. I was a good reader. I had never taken a course about writing or been in a workshop. I didn’t know any other writers. And, of course, it was the time of the boom of Latin American literature, and they were all male. They were all men. And it was happening in the periphery of my life. I was reading their work, but I could never even dream of getting in touch with any of them.

AMY GOODMAN: The world-renowned writer Isabel Allende. Her latest novel, The Wind Knows My Name. She’s the author of 26 books that have sold more than 77 million copies and translated into more than 40 languages. She just recently turned 80 years old. To see all our interviews with Isabel Allende, visit democracynow.org. That does it for our show. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options