Guests

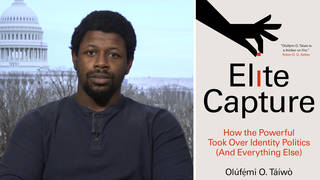

- Christian Cooperboard member of New York City Bird Alliance, writer, LGBTQ activist and host of Extraordinary Birder on the National Geographic channel.

We continue our July 5 special broadcast by revisiting our recent conversation with Christian Cooper, author of Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World and host of the Emmy Award-winning show Extraordinary Birder. We spoke with Cooper after New York City’s chapter of the Audubon Society officially changed its name to the New York City Bird Alliance as part of an effort to distance itself from its former namesake John James Audubon, the so-called founding father of American birding. The 19th century naturalist enslaved at least nine people and espoused racist views. Christian Cooper is a Black birder and a longtime board member of the newly minted New York City Bird Alliance. In 2020, he made headlines after a white woman in Central Park called 911 and falsely claimed Cooper was threatening her life. Cooper also shares stories of his life and career, including his longtime LGBTQ activism and how his father’s work as a science educator inspired his lifetime passion for birdwatching.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

It was four years ago, in May 2020, when our next guest, Christian Cooper, made national headlines when a white woman in Central Park called 911 on him, falsely claiming that Cooper, who’s Black, was threatening her life. The woman, Amy Cooper — no relation to him — made the call after Christian Cooper asked her to follow park rules and put her dog on a leash. They were in an area of the park popular with birders, the Ramble. Video of the incident went viral, in part because it happened on the same day that Minneapolis police murdered George Floyd. We’ll talk about what Christian Cooper calls the Central Park incident in a minute.

He would go on to write a memoir titled Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World. The paperback has just come out. He also hosted the National Geographic episode series Extraordinary Birder, for which he just won a Daytime Emmy Award in the Outstanding Daytime Personality category.

In June, New York City’s chapter of the Audubon Society officially changed its name to the NYC Bird Alliance. John Audubon, the founding father of American birding, was a 19th century French American naturalist — and a slaveholder who espoused racist views. In March, the National Audubon Society voted to retain the Audubon name. That set off a revolt among leaders of local chapters of the society.

Democracy Now!'s Nermeen Shaikh and I recently spoke to Christian Cooper, longtime board member of what was the Audubon Society here, now called NYC Bird Alliance. Also, he's a longtime LGBTQ activist and served as co-chair of the board of directors of GLAAD in the 1980s. I began by asking Christian about the NYC Bird Alliance’s decision and who John Audubon was.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Well, first of all, what you can’t take away from him is that he put birds, North American birds, on the map. And that was principally through his amazing art. We’re lucky enough to be in New York City, where the New York Historical Society has the original Audubons — not the original prints, the original paintings. And I was lucky enough to see those at the New York Historical Society. And they are astonishing. They’re gorgeous. You can’t take that away from the guy.

You do have to put an asterisk on it, which says, “Yeah, and his work was funded by the trafficking in other human beings.” And it’s that part that makes it very difficult for us, looking forward, when we’re trying to diversify birding, which traditionally has been a very, very white activity, in the most diverse city in the world, or certainly in the country. So, this name became an impediment to our efforts to diversify. And because we’re trying to look forward, we’re like, “Yeah, we’ve got to ditch it. We’ve got to lose it. We’ve got to get a name that doesn’t present a barrier to everybody’s participation.” We’re throwing the doors open for everybody and saying, “You’re all welcome in birding.”

AMY GOODMAN: But the National Audubon Society has not decided to go this route. What are the chapters, some, like Seattle?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Right. Seattle has picked a new name. Wisconsin, a couple of Wisconsin chapters have picked a new name. Illinois has picked a new name, or Chicago has picked a new name. I lose track. There have been so many that have changed names. And a lot of us, though not all of us, have settled — oh, Georgia picked a new name. But a lot of us have settled on Bird Alliance as the new name. So we are now the NYC Bird Alliance.

And the hope is that — and the idea is not, you know, to erase Audubon, to cancel Audubon. You can’t. The man’s history is what it is. You know, like I said, you’ve got to give it an asterisk, but it’s there. It’s real. But that doesn’t mean you’ve got to have that name on your organization, particularly when you’re trying to take an organization that for so long has been almost exclusively white and you’re trying to get other people involved. You know, you don’t — for example, imagine you were a country club that had a history of excluding Jews. And you’re like, “Oh my goodness, we’ve got to change that. We’ve got to invite some Jews. Hey, guys, don’t you want to join the Josef Mengele Country Club?” How many Jews are you going to get? You’re not. That’s kind of — that’s kind of what we were facing with Audubon. So, it’s not a matter of erasing him. The history is still there. It comes with an asterisk, but it’s there. But looking forward and getting everybody involved.

And why is it so important to diversify? Not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because we have lost one-third of our birds in North America. I’m not talking about species. I’m talking about raw numbers. The populations are down, in my lifetime. I know this, because I go out there, and I bird, and I feel it, and I see it. And we all do. We have lost one-third of the birds in North America just in my lifetime, since I started birding when I was about 10 years old. And the only way we’re going to turn this around — because we can turn it around; we’ve done it in New York City, in some ways — is if we get everybody involved in birding that possibly could be interested, because the country is diversifying. New York City is already a diverse city. If we don’t have all hands on deck, we’re not going to be able to save the birds.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Christian, you exploded onto the national scene a few years ago because of an incident in Central Park. And let’s go back to that day. We’re talking about Memorial Day 2020. So, it’s in the height of the pandemic. Everyone is masked. There are no vaccines. It is, horrifyingly, also the day that George Floyd was killed. But when you were out in Central Park that morning, he was still alive. And we want to turn to what happened on that day. Describe to us what time you went out in the morning and what you were doing and then what happened.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Condensed version: I got out at 5:30, which is my usual time to hit the park that time of year. I’m looking for birds. It was a relatively slow day. There was a particular bird called the mourning warbler, which is typically one of the last warblers to come through in the migration. So, this is very late in the migration. And I’m looking for a mourning warbler. Mourning warblers are skulkers. They stay close to the ground, for the most part, hidden in the shrubs. So, I’m heading towards this patch of shrubs to look for a mourning warbler.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you know it was there?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Oh, I didn’t know it was there. I’m hoping to find it. So, I’m keeping my ears open for ”Chery, chery, chery, chweer. Chery, chery, chery, chweer.” That’s the song of the mourning warbler. And if I hear that, then I know there’s one hiding in those shrubs, and I’ve got to wait him out and look for him.

So, I’m heading for a patch of habitat of low-lying growth, where I’m likely to find one. And then I hear, “Henry!” at the top of the lungs, the way nobody would talk to a human being, so I know it’s a dog off the leash. And then I see it tearing exactly through the low-growing growth where I was hoping to find a mourning warbler. I’m like, “Well, if there was one there before, there’s not one there now.”

So, this is an ongoing problem in Central Park, particularly in the Ramble, where dogs have to be on the leash at all times. There are signs posted everywhere telling everybody that. So, this has been an ongoing war between certain dog walkers — I don’t want to tar all dog walkers with a bad brush, because there are some who actually follow the rules. But this has been an ongoing war for many, many, many years between dog walkers and birders.

And so, you know, we got into it. I’m like, “You know, look, your dog’s supposed to be on the leash. The sign’s right there. Look, all you have to do is take the dog across the road there to that other part of the park or outside the Ramble. You can have your dog off the leash until 9 a.m., and we’re all good.” She was having none of it. Eventually, she ends up picking up the dog by the collar.

AMY GOODMAN: Not leashing it, but picking it up.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Right, right.

AMY GOODMAN: By the collar.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Right, yeah. Let’s not relive the whole thing. But the bottom line is, I start recording her with my iPhone, because that’s one of the strategies we have when people are breaking the rules, is to document it. It puts pressure on them, because most people don’t like to be recorded breaking the rules, and it’s documentation for us to show the Parks Department.

AMY COOPER: Please take your phone off.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Please don’t come close to me.

AMY COOPER: Then I’m going to [inaudible]. I’m calling the cops.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Please call the cops. Please call the cops.

AMY COOPER: I’m going to tell them there’s an African American man threatening my life.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Please tell them whatever you like.

AMY COOPER: I’m sorry, I’m in the Ramble, and there is a man, African American. He has a bicycle helmet. He’s recording me and threatening me and my dog. There is an African American man. I am in Central Park. He is recording me and threatening myself and my dog. And like — I’m sorry, I can’t hear you, either. I’m being threatened by a man in the Ramble. Please send the cops immediately! I’m in Central Park in the Ramble. I don’t know!

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what happened with that video then.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: You know, I put it on Facebook, because I have a tendency to put what happened that’s notable to me on Facebook after a day of birding. Usually it’s a bird. This was not a bird. But I put it on Facebook. Immediately, one or two friends called me up and said, “Can you make this public so I can share it?” And I’m like, “All right, fine.” And then my sister called me, and she was seething, understandably. And she said, “Can I put it on Twitter?” And I’m like, “OK, yeah, sure. Put it on Twitter.” And then it just kind of exploded and became a thing, and, you know, became even more of a thing because it ended up being on the same day that George Floyd was murdered.

So, you know, it was a window, I think, for a lot of people into what we African Americans know, because we live it every day. But I think for a lot of people who aren’t African American, they were able to see in those two videos, you know, the use of racial bias and how it informs policing, or people try to use it in policing sometimes, and then the actual police response, you know, against African Americans that gets us killed. So, it opened some eyes, I think, maybe, that hadn’t been open before, for a while.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Did the police come?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: They did eventually come, or, as I understand it, but, by then, we were both long gone. You know, I considered at the moment staying around to clear things up with the police. And then I thought, “No, she doesn’t get to do that. I’m here to bird, and I’m going back to birding. And, you know, and if I run into the police, fine, then I’ll tell them what happened. But, meanwhile, I’m looking for birds.” And I did that. And no police came. And then I left the park and went home.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you find the warbler?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: I did not find the mourning warbler that morning.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Cyrus Vance was the Manhattan DA. Talk about what they wanted to happen, and your response, overall, and what happened to Amy Cooper.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: So, the bottom line is, Cyrus Vance wanted to — you know, it was a very public case. So, the Manhattan DA wanted to prosecute her for filing a false report, which is fine. You know, that’s his prerogative. He wanted my participation in that. And that’s where I had to make a decision as to whether or not I was going to pursue it. And I chose not to. And that was a hard decision. And I know a lot of people, especially Black people, you know, were not happy with that decision. But I had to kind of trust my conscience, and my conscience said — you know, her life had imploded. She lost her job. She was a pariah nationwide. You know, if none of that is going to send a message to people this is not the thing to do, then I’m not sure anything will. It felt like piling on, on my part. And so, I was just like, “You know what? You have the ability to pursue these charges without me. Please, you know, go ahead and do so if you feel the need. I don’t feel like I need to participate in this.”

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, if you could talk about who introduced you to birdwatching, or at least the possibility of birding, and what it enabled for you, this engagement with nature and with birds, in particular?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: My father was a science teacher for his whole life, and for a good stretch of that, a biology teacher, so nature was always very important to him. And he took us camping a lot as kids. So nature was always very important in our household. For me, for whatever reason, it took the particular form of birds. I built a bird feeder and put it up in the backyard. And I saw this bird coming to it. And it was all black with a patch of red on the wings. And I was like, “I’ve discovered this new species of crow!” And I was, like, excited with my, you know, tour de force of youthful scientific discovery, and then found out it was red-winged blackbird. But it’s still one of my favorite birds to this day. And that’s what you would call my spark bird, which is — in the lingo of birdwatchers, that’s the bird that gets you started birding. And after that, it was just sort of like going down the rabbit hole. So, that’s what started it, at about 9 or 10, and I just kept at it.

And then my dad took me to the bird walks of the South Shore Audubon Society, which at the time were led by this guy named Elliott Kutner, who was just like ebullience personified. And he took one look at me and my interest in birds, and he was like, “This one’s mine!” And from then on, you know, it was — he was great. He nurtured that and that interest.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And how did it come to serve as a kind of — because you mention that several times in the book — as a kind of refuge from the different forms of marginalization or exclusion that you felt, both as a Black man and also as someone who’s queer?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Yeah, and also it was a part of the marginalization, ironically, because, you know, being a birder in the ’70s in junior high and high —

NERMEEN SHAIKH: It’s true.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: — is not going to make you the most popular kid on the planet.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: No, you’re right.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: No, but what it is — and this is true for everybody, I would say — is that birding forces you outside of yourself, whatever your woes are. For me, it was, you know, being in the closet, because I knew I was gay from like the age of 5. So, for me, it was being in the closet. You know, if you’re worried about your rent, if you’re worried about, you know, “Oh my god, my life is a misery. I have this illness,” or whatever, and then you get outside, and you’re looking for birds. And so, first of all, you’re in this beautiful natural setting, or semi-natural setting, so that calms you down, takes you outside yourself. But then, if you want to see birds, you’ve got to focus. You’ve got to be listening and looking, or else you’re not going to see any birds. And when you do that, you’re engaging with the world around you in such a way that, whatever those woes are, for at least a little while, they fall away. And it’s very meditative. It’s transporting. It makes you feel connected to the whole planet. It engages your senses, your intellect. It is incredibly healing.

And that’s one of the reasons why I’m like, “Black people, do this!” Because if there’s anybody in this society that needs healing, that needs to have our woes fall away for a while, it’s us. And then add the fact that, you know, birds are the ultimate symbol of freedom, because there is no part of the planet that is inaccessible to them. They can fly. They are symbols of freedom. So, for a people whose history is about being enslaved, for us to be able to relate to this bird, it’s liberating. So, that’s why I think birding was so important for me as a kid, and why I just think everybody, but particularly Black people, should be birding in droves.

AMY GOODMAN: Christian, I also want to ask you about your National Geographic series Extraordinary Birder with Christian Cooper. You just won a Daytime Emmy in the Outstanding Daytime Personality category. And I wanted to turn to the introduction, that plays at the beginning of each episode.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Look at all those ravens.

I’m Christian Cooper, and I am a birder.

Ah, that was cool!

My dad was a biology teacher and gave me my first pair of binoculars when I was about 10 years old, and I never put them down.

Wow! Not something I’ve seen in my life.

Now I’m traveling the globe to explore the world of birds —

That’s amazing. It’s like a cloud.

— and their relationship with us, those of us who don’t have wings. And along the way, I’ll show you what I adore about these crazy smart —

Your first look at the outside world!

— dazzling —

It’s fantabulous!

— and superpowered feathered creatures.

AMY GOODMAN: This is a clip from the Extraordinary Birder episode called “Birds of Puerto Rico,” again, hosted by our guest, Christian Cooper.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: The best part of birding on an island is finding species that can’t be found anywhere else. We birders call them endemics. This place is home to 17 endemic species of birds, and I’m hoping to spot a few of them to add to my life list.

The Puerto Rican parrot is a special bird. With its bright green and blue feathers and red striped brow, it’s the pride of all Puerto Ricans. Way back, the island’s Taíno Indians named it iguaca, after the squawking sound it makes when it flies. Sadly, nature has dealt the iguaca a bit of a rough hand. And between hurricanes, hungry predators and a lack of environment protection, they were down to just 13 birds in the wild in the early 1970s. Now there’s a plan to bring them back.

AMY GOODMAN: A clip from Extraordinary Birder, National Geographic series. Christian Cooper just won an Emmy for this series. It’s amazing. So, tell us the countries that you went to for this series.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Well, that’s the thing. Because it was COVID and because of budget, they kept us domestic for the season. So, we went to Palm Springs, California; New York City; Washington, D.C.; Puerto Rico; Hawaii — oh, boo hoo, boo hoo, I had to go to Hawaii — and Alabama. And the Alabama episode was the most important to me, because that was the collision not just of birding, but of family history and civil rights history. And you would be surprised how these things can inform each other. And we explored that a little bit in the episode. I had gone down to Alabama a year earlier at the invitation of Alabama Audubon. And the experience for me was so enlightening, but I wanted to recreate it for the viewers. So the Alabama episode is my favorite.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us more about Alabama and how all these worlds intersect.

CHRISTIAN COOPER: Sure. Well, for example, I walked across, for the first time, the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which is where Bloody Sunday happened. And so, I’m walking across and thinking about what happened on this bridge. And meanwhile, there are cliff swallows that are nesting underneath it. And I realized, you know, these cliff swallows were probably here all those years ago, and they witnessed. They were there. They were part of that history, to be there when all that happens. So, there’s that connection.

Then there’s other things, like my father’s family. You know, we’re all Northerners for generations. But you go far enough back in the history of any African Americans, and our roots are in the South. And my dad’s father’s side of the family came from Alabama, but I had never been. And I didn’t want to go, because I’m like, “My family left there for a reason.” I had never been to the Deep South. But the chance to go in the tender arms of Alabama Audubon made it — I’m like, “Well, if there’s ever going to be a chance to go, this is it.” So I went.

And it was fascinating to see what expectations were violated, what expectations were affirmed — for example, walking around in Birmingham, and there are all these cafes with rainbow flags in the window. And I’m like, “Wait, wait. What?” But, you know, that actually makes sense, because, you know, you go across the country, and in the urban areas, they tend to be pretty progressive and actually very welcoming of queer people. But then you go outside. Even if you’re in New York, you know, you’re here in the city, and it’s very welcoming to queer people, but if you go to regions upstate, you know, there are parts where it’s redder than red Iowa, or something like that. So, you know, that was a revelation to me.

But then other things, like the fact that, you know, my family had left Alabama and come to the North. Why? Because there was — you know, that was part of the Great Migration, when Black people left the South for opportunity in the North, economic opportunity, jobs, and to escape oppression. That’s exactly what birds do every year. That’s why they migrate. They leave the South for the North, because there are resources in the North that they exploit to raise their young and be more successful and pass on a better life to the next generation. That’s why Black people left the South. And we even use the same word, “migration,” for the birds, the “Great Migration” for Black people. So, things like that, you know, just all sort of collide and inform each other and change your view of things.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And then, you know, as you said earlier, for the National Geographic series, you weren’t able to travel abroad because of COVID and so on. But you did — and you write about it in the book — you did actually go to several countries on your own, including Nepal, Tanzania. You said earlier that you had also been to Belize. I mean, these are countries that are at the forefront of the climate crisis, which is, of course, also threatening all forms of nature, including birds. So, if you could say a little about what you saw in these places — and this is obviously a limited number; I imagine you’ve been to many other places to bird — and the concerns you have about the climate crisis and the threat that it poses to bird life?

CHRISTIAN COOPER: The best example I can give you is a trip I took in December down to Antarctica. I know. It was amazing. It’s like visiting a different planet. But we got down there, and I was sort of, you know, a special guest on the boat, and so I wanted to be helpful to the other people on the ship and tell them, “All right, we’re going to make our landing at this particular spot.” And I researched what kind of penguins we were going to see there. And I said to everybody, “All right, well, this is the penguin we’re likely to see at this spot.” And we get there. I said, “This is a colony of Adélie penguins.” And we get there, and it’s almost entirely gentoo penguins. And I’m like, “Ugh, I botched that completely.” The penguin researcher on the boat said to me, “No, you don’t understand. I was here two years ago, and that colony was almost entirely Adélie penguins.”

Adélie penguins are true Antarctic penguins. They rely on ice for making their livelihood. Gentoo penguins are what they call sub-Antarctic penguins. And the lack of ice is what lets them spread. So, the fact that in two years that colony had converted almost entirely from Adélie penguins, the Antarctic penguins, to gentoo penguins is a sign of just how quickly climate change is happening, particularly down there, because it’s changing faster at the poles than anyplace else. So, we were able to see in real time ourselves that our climate is changing way faster than most creatures can adapt. And, you know, there will be winners and losers. You know, gentoo penguins, at least for a while, are going to have an advantage. But what’s scary is that most species can’t adapt to change successfully that’s that fast, including us.

AMY GOODMAN: Christian Cooper, board member of the NYC Bird Alliance, writer, LGBTQ activist and host of the National Geographic series Extraordinary Birder with Christian Cooper. His memoir is just out in paperback, Better Living Through Birding: Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World. Visit democracynow.org to see a longer version of this interview.

And that does it for today’s show. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options