Guests

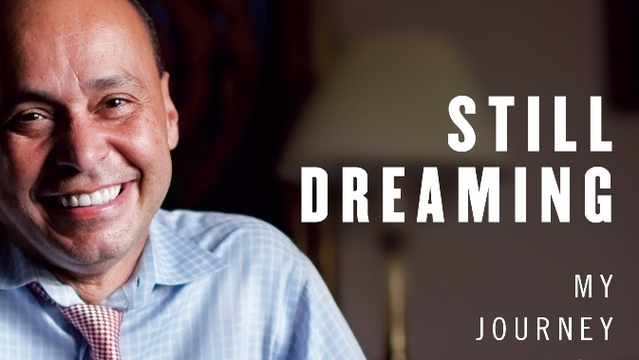

- Luis Gutiérrez(D-Illinois). He is the Chair of the Immigration Task Force of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus and a member of the bipartisan House Gang of 7 that has been working on a broad immigration reform bill. His memoir, “Still Dreaming: My Journey from the Barrio to Capitol Hill,” has just been published.

We recently spent the hour with Rep. Luis Gutierrez, who says Congress has enough votes to pass comprehensive immigration reform by the end of the year. In the meantime, read a chapter of his new memoir, “Still Dreaming: My Journey from the Barrio to Capitol Hill.”

Excerpted from Still Dreaming: My Journey from the Barrio to Capitol Hill by Luis Gutiérrez with Doug Scofield. Copyright © 2013 by Luis Gutiérrez and Doug Scofield. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Chapter One: “Ring of Fire”

It wasn’t the heat or the smoke that woke me, it was the crashing sound, like a car accident right in my living room. I opened my eyes and saw flames shooting all the way from my floor to the ceiling.

Even though I was disoriented from coming out of a dead sleep at three fifteen in the morning, I noticed the fire didn’t look normal. It looked as if it were created by the special-effects guy in a science-fiction movie. It swirled like a Hula-Hoop of flames, blasting up fast from the floor, like the song “Ring of Fire”—except real.

Waking up to a crash and a burning living room gets you moving quickly. It was hot, and the ceiling was turning black. I jumped off the couch, where I had fallen asleep, and ran up the stairs, shouting to my family to get out of the house. I went to my daughter Omaira’s bedroom in the back of the house and grabbed her, still sleeping soundly. Then I sprinted to our bedroom, directly above the burning living room, to get my wife, Soraida. She was already heading down the hallway, still groggy. She had heard the crash too. I yelled, “The house is on fire, we have to get out!” Carrying my little girl in my arms, we ran down the stairs, straight for the front door. We could see that the entire living room was burning. The couch was on fire and the flames were attacking the ceiling.

I had dry-walled that ceiling myself, and gone to the emergency room when I stepped on a nasty, rusty old nail from one of the boards I’d ripped from the ceiling. Our house was an old, single-family, brick home. It was our little part of the American Dream. It had big double windows in the front and a postage-stamp-size Chicago front yard, where we had planted azaleas. We had three small bedrooms on the second floor. The house was a wreck when we bought it, and we had done most of the work ourselves. I wanted it to be the nicest house on the block, determined not to let even one of my mostly white neighbors think the new Puerto Rican family was ruining their nice community. Now our home was going up in flames.

It didn’t take us more than a minute to grab Omaira. By the time we headed down the stairs, the living room was practically destroyed. It was 1984, long before cell phones, so we were nearly out the front door when it occurred to me that we hadn’t called the fire department. I handed Omaira to Soraida and doubled back inside to call 911 from the phone in the front hallway. It was hot and I was sweating. The walls looked like they were melting. I shouted “Fire, 2246 Homer!” into the receiver and then ran down the front steps, away from the flames.

Just then the front windows exploded from the heat, spraying glass into the front yard. Some of the shards landed inches away from me, close enough to make me wonder why I hadn’t called 911 from a neighbor’s house. Lights went on up and down the block and the street started to fill with curious and concerned neighbors. We lived three blocks from the fire station and you could hear the sirens almost immediately. Now the flames were jumping out of the first floor windows and the smoke was rising toward the second story, where my wife had been sleeping five minutes before. Soraida, Omaira, and I stood quietly and watched our house burn.

I loved our house. I couldn’t believe we were losing it. I thought about my daughter’s room filled with her huge stuffed Big Bird that she loved so much, our wedding album by the TV in the living room, my record collection. Then I thought about how much worse it could have been, about how rare it was for me to fall asleep downstairs.

Soraida and I had gone out to dinner with friends that night. On the way home, I stopped to get the early Sunday edition of the Chicago Tribune, to catch up on the Mondale-Reagan coverage, hoping that Mondale might still have a comeback in him. It was October, a mild Indian summer night; Soraida had put Omaira to bed and I fell asleep watching the news and reading the paper. Our house was quiet—so quiet that Soraida and I had slept soundly while burglars stole everything from unpacked boxes we’d left downstairs the very night we moved in. If I had been sleeping upstairs, and the crash hadn’t woken me right away, we might have been jumping out a back window to escape the fire. Or maybe we wouldn’t have gotten out at all.

Omaira did what any five-year-old would do; she cried and asked about her toys, her room. We told her we would save everything we could, but as I looked at the house I didn’t think we were going to save much besides ourselves. Soraida took Omaira to our neighbor’s house and they called my wife’s sister, Lucy, to tell her we would need a place to stay for a while.

Before long, the firefighters were there, breaking more windows to let out the heat. The water from their hoses gushed into the living room. It didn’t take long to get it under control, but as I looked at the giant streams of water pouring in through the windows I knew that whatever the fire didn’t get, the water would.

As the firefighters moved their hoses around for better angles, a Chicago Police Department cruiser pulled up. I hadn’t yet completely embraced the idea that the police could be your friends. I was a Puerto Rican who grew up in a neighborhood where cops stopped you whenever they felt like it. They asked you and your teenage friends where you lived and what you were doing and where you were going. They assumed you existed to cause trouble. Seeing the police as allies didn’t come naturally to me.

So I wasn’t expecting a warm blanket, hot coffee, and a lot of sympathy from the police, but I thought the officer might at least have gotten out of his cruiser. Instead, he turned on his spotlight and motioned me over to his car. He stayed in the front seat with his report book open. He hardly looked at me while he took notes, as if it were nothing more than a routine fender bender. He didn’t seem thrilled to be called out to a burning building on a Saturday night. His physique suggested he wasn’t crazy about much of anything that required movement.

“This your house?”

I told him it was, and what happened. I described the crash that I had heard and the way the ring of flames had shot up from the middle of the room to the ceiling.

“Probably an electrical fire,” he said.

I told him I had rewired the whole house and put in 220-amp circuits. I wanted him to understand my hard work, that I was a responsible homeowner. Besides, the fire looked like it had started right in the middle of the room. And what about the crash?

“Probably something with the boiler.”

“But there is nothing wrong with the boiler,” I said. “It’s a warm night, it’s not even on. The boiler’s in the back of the house.”

“The TV probably overheated.” The officer had still barely looked at me.

I try to get along with people. Really, I do. That’s a statement some people would laugh at, including Republican members of Congress who’ve fought with me about immigration, or Democratic members of Congress who’ve fought with me about stopping their pay raises. I can hear laughter from Chicago aldermen who screamed at me when I read—out loud, on the city council floor—the surprisingly low amount they paid in property taxes. The president of the United States, who saw me get arrested on Pennsylvania Avenue in front of his house, might even be amused at that assertion. But I do try to be agreeable.

I have my limits. I had just raced up and down my stairs to get my family out of my burning home. Many of my belongings were smoldering twenty feet away. My burning couch was lying in my front yard, where it had been tossed by the firemen, and it was crushing my azaleas. My daughter was crying. My heart was still pounding. I didn’t expect much sympathy, but in exchange for my tax dollars and my burning house, I was hoping for at least a little courtesy. But it was obvious that the policeman assigned to the fire that night was about as interested in figuring out what caused it as he was in running the Chicago marathon.

I resisted the urge to call him the names that were on the tip of my tongue; instead I explained to him why I didn’t think it was the TV. Or the boiler. Or the wiring. I was still talking when he looked up at me for the first time and said, “Board it up and call your insurance company.” And he drove off.

By 1984, I had come a little ways from being just another kid in a poor Chicago neighborhood who stood politely with my hands on a car hood whenever a policeman stopped me on my own block. So instead of just calling my insurance company, I also called my new boss, Ben Reyes, the deputy mayor of the city of Chicago. He reported directly to the mayor, a mayor I would soon meet with pretty regularly. I explained my situation. My house had burned and the police weren’t exactly being helpful. He called the deputy mayor in charge of the police and fire departments. Just as the last flames from my house were crackling out and the smoke was starting to drift away, two younger and more interested investigators from the bomb and arson squad showed up. They had gotten a call.

I told them what happened. The crash, the weird cone of flame. They didn’t look at me like I was crazy. They were less interested in their report book and more interested in what I had to say. We talked while the water dripped off the front of my now-exposed living room and the house started to cool down.

The younger investigator said we should go in and look around. It looked dangerous to me, but I was eager to see what I could salvage. The glow of his flashlight illuminated what was left. The fire department had put the fire out quickly, and the back of the house was still in decent shape. The front—upstairs and down—was burned down to the floors, framework, and bricks. I hoped I could save a few toys from my daughter’s bedroom, maybe a few things from the kitchen. There wasn’t going to be much. As the investigator and I carefully walked through what used to be my living room, he stopped. It was hot. He sniffed and looked at me.

“Electrical fire, huh?”

I wasn’t sure if he was making fun of me or the other cop. His flashlight scanned the floor, then stopped.

“You collect bricks, Mr. Gutiérrez?”

He shined his light on a brick smoldering in the debris, just a few feet away from where I had been sleeping on the couch.

“No sir, I don’t collect bricks.”

“You ever seen that brick before?”

He moved his light over the area around the brick, and then looked back at me.

“Have you been drinking, Mr. Gutiérrez?”

I wasn’t quite sure whether to be mad or amused.

“No, I haven’t been drinking.” And I hadn’t. My only liquid vice is drinking Coca-Cola for breakfast.

“Well, that sure looks like the bottom of a big jug of wine to me,” he said.

He was right. Near the brick was the still-intact bottom of a Gallo or Paul Masson wine jug. It looked like a green Frisbee made out of glass.

Then he leaned down and found the handle and the top of the jug, with part of a rag still sticking out of the hole. He held it up. He was smiling. He pushed the rag up toward me.

“Take a look at this, and smell the house. What do you smell?”

I hadn’t thought too much about the smell—it just smelled like fire and smoke. It smelled like it was going to cost me a lot of time and money. But once I really sniffed, the smell was unmistakable, the same thing you smelled every time you pulled into the Mobile station. It smelled like gasoline.

I was still confused.

“Why the brick?”

“They threw the brick through the window. That was probably your crash. Then they threw the jug filled with gasoline through the hole where your window used to be. The jug filled with gasoline won’t break the window. It would just break and catch on fire when it hits the window. That just gives you an exterior fire, and they wanted to make sure they got the gasoline inside the house.”

“But why?” I asked, still not quite convinced.

He looked at me like I was a little slow.

“Because they wanted to hurt you.”