Topics

Guests

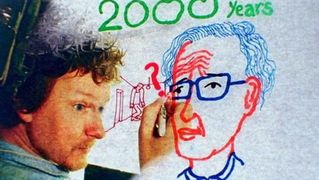

- Michel Gondrydirector and animator of the new documentary, Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? His past films include the Academy Award-winning Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the musical documentary Dave Chappelle’s Block Party and The Science of Sleep.

- Noam Chomskyworld-renowned political dissident, linguist and author. He is Institute Professor Emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he has taught for more than 50 years.

At the world premiere of the new documentary, Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? in New York City, filmmaker Michel Gondry sat down with the subject of the film, Noam Chomsky, the world-renowned linguist and activist. The discussion took place on November 21 at the DOC NYC Festival. The discussion was moderated by Anthony Arnove.

Democracy Now! has interviewed Noam Chomsky many times over the years. Click here to see this archive.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: So, first of all, Michel, I want to thank you. I just think this is a really truly remarkable film. And—

MICHEL GONDRY: Thanks.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: And it’s a real gift, I think, in a way a work of art really can genuinely be a gift. And I also think you’ve done a remarkable thing in that I’ve known Noam around 26 or 27 years; I was able to get him to a film once in that entire 27-year period. You’ve now managed to get him to see this film twice in less than a year. So I think that’s also a remarkable gift to Noam and to the world, to drag him away from the computer for a few hours and get him out and to bring him here with us. So I want to thank you for that, as well, Michel.

MICHEL GONDRY: Thanks. I’m glad.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: I wonder if you could start by talking—this process started 2005 and, you know, what the germ of it was for you, and then what—a bit of what the journey was to being here today.

MICHEL GONDRY: Well, I met with Noam actually, yes, 2005, because I was visiting MIT as an artist in residence. That was organized by Michèle Oshima, who is here. And I realized that Noam was, I guess, still teaching there at the time. And I was visiting a lot of student and teacher to see all the programs and—because there is this work that’s being done there that’s really bridging between art and science, which is a territory that I always was interested by. So I met with Noam, and after a few session, I proposed to Noam to do a series of interviews and use abstract animation to illustrate them. And I don’t know if you remember, Noam, I showed you a little clip that I had done. And it was a starting point, and you said yes immediately. And I was always very, of course, impressed by your work, and as well because what was really attracting me is your scientific work, and it’s always great to see—to be able to capture the image or the voice of somebody alive who has already such a huge legacy, because I watch—I was talking about Richard Feynman and all of these great scientists who are not here anymore, and I wish I had known them. And I thought it was important for me to try to establish that.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: So, Noam, I wonder if I could ask you a bit about this intersection that Michel is raising about connections between art and science. You know, one of the fascinating things about this film is we see Michel’s process as an artist as he’s trying to engage with your ideas and his misunderstandings and other currents of thinking. I wonder if you could talk about your own practice of doing science. What does it actually look like for you? What is your process, you know, when you’re tackling a scientific question, when you’re coming up against an aporia in your work?

NOAM CHOMSKY: It’s kind of like what Michel captured so—with such remarkable artistry in the film. It’s usually a matter of going for a walk and thinking about things, talking to somebody, hoping that somehow what looks paradoxical or impossible will somehow fall into place. How it happens, I don’t think anyone knows. It’s—I’m sure it’s the same when you’re—anyone is creating an artistic work: It just somehow comes.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: What would be a problem like right now that you would say you’re dealing with in your work or in a particular aporia currently?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Currently?

ANTHONY ARNOVE: Yeah.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, the point that Michel emphasized, correctly, is—and at least has been a driving force to me, not for everyone in the field—is to try to show what ought to be true, to try to demonstrate what ought to be true. It ought to be true for various reasons, some of which indicated in the film, that the basic essential nature of language is, first of all, uniform for all languages, which is why children can learn any of them. And it is also fundamentally very simple. But when you look at the data of language, it looks extremely complex. But that’s true of anything you don’t understand. If there’s anything you don’t understand that looks hopelessly complex, the idea is to try to see if you can extricate from the complexity fundamental principles, which somehow make things fall into place which otherwise didn’t make any sense, like the one principle that was mentioned at the end of the film about seeking a minimal structural distance. You can pursue that much farther. And a lot of things fall into place, including the way in which quite complex sentences are interpreted, if you continue to pursue the idea that there just has to be fundamentally simple processes that interplay in a way which yields observed complexity. So that’s the basic work that I’m involved in, just that one paper coming out. I have another one soon. A lot of technical questions about this.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: Michel, I think there’s a very interesting theme that runs throughout the film, and I wonder if it doesn’t also speak to your other films. As I read them, I feel like there’s a fundamental curiosity that drives your work in a—what Noam refers to as a puzzlement, that—looking at things that might appear to be obvious, but being puzzled by them. I wonder if that is something that you think of in your own practice and if it might apply not just to this film, but to your earlier work, as well.

MICHEL GONDRY: Yes, sure. I mean, I always—like any kid, I ask many questions to my parents, and they always ask why. And at some point they get tired of it, and you have to figure out somehow yourself. So, there is something that I remember figuring out by just my questioning, my own questioning. And sometime I would verify the answer, but I always have this curiosity to understand what was going on with the world. And when I was a kid, I—Catholicism didn’t work. We went to some cult and had some—my mother took me to some meeting that were really weird, and they didn’t satisfy me. And I found in science some—some more constructive answer, that the idea that you can build something on the ground that people agree upon. And it’s one of the things that attracted to Noam’s work and philosophy. It’s this idea that you are—like French philosopher, they say, oh, everything is up in the air, and it’s foggy, and it’s—it’s very abstract. And I think it’s important that you can like try to agree on the ground, so you can build on that. So, in my movies, I mean, it’s not necessarily apparent, but I always had this curiosity.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: And could you—I’d actually like to ask both of you about this, the difference between kind of the process of self-education and your formal schooling, because it seems like both of you have engaged in a process of learning outside of or that went beyond the period of formal education. And, you know, in your case, maybe you could start, Michel, talking about art school and your experiences in art school and the limitations of formal schooling in your own experience.

MICHEL GONDRY: Yes, I went to art school pretty early, like high school was art school. So I didn’t develop the academic very—very much. I was intrigued and interested into geometry, and I was pretty good at it, and perspective. And I remember being good at that, but I never—maybe I thought that art—or that’s why I use this abstraction in animation. I could translate complexity without to go through all of those books that you’ve read. And I—I mean, I read a bit, and I still reading, but of course it’s—I don’t feel very up to Noam’s level. But that’s why I use abstraction here, because I think I’m not trying to demonstrate Noam’s findings. I’m trying to convey my feelings on the—I think it’s more accurate this way. I mean, only at the end I really—I mean, actually, all the time, at the end I really did the work, and I’m sort of proud of, like choose a sentence and really to [inaudible] from your graphic. And it was difficult, but I wanted to really understand it, the difference between the structural and the linear length of the—position of the word, of the verb. So, I’m not sure I remember the question now, but sorry.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: It’s fine. It took us to an interesting place, Michel. What about you, Noam? Could you talk about—I mean, obviously you grew up in a family of educators, and you did go through a formal process of education, but you’ve continued your education in very profound ways and outside of some of those formal boundaries, as well.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, I don’t want to be corrupting the youth, so I’m not sure—

ANTHONY ARNOVE: No, no, we want to be corrupting the youth.

NOAM CHOMSKY: I’m not sure I ought to tell the truth. But—

ANTHONY ARNOVE: Tell the truth.

NOAM CHOMSKY: The truth is, I have absolutely no professional credentials—literally, which is why I’m teaching at MIT. They didn’t—that’s absolutely true. They didn’t care. You know, it’s a science-based university. They didn’t care if you had a guild card, something or other. So, we saw a little of it there. But I hated high school. It was the academic high school in the city, the one that all the kids went to who were going to go to college, so teachers didn’t really have to work very hard, because we were going to pass the exams anyway. And I couldn’t stand it. And this is 1945, so there were no questions about going to some college somewhere else. You lived at home, you worked, you went to the local college, period.

Local college happened to be the University of Pennsylvania. I, as a high school student, looked at the—looked through the catalog. Looked really exciting, all these great courses in all sorts of different fields. I was really looking forward to getting out and going to college. After my first year of college, each course I took in every field was so boring that I didn’t even go to the classes. I mean, the way—I was quite interested in chemistry, but the way I passed the chemistry course was because I had a friend, a young woman about my age, who took extremely meticulous notes in red and blue and so on, and she lent me her notes so I didn’t have to go to class and I could pass the exams. You had to go to—there was a lab. And I knew, you know, if I try to carry out a lab experiment, it’s not going to work, period. But there was a lab manual, and it was obvious what the answers had to be, so I just filled in the answers, and I never even went to the lab. And then I had my comeuppance when I had to apply the next semester, because I was charged $17, which was a lot of money in those days, for lab breakage. And I couldn’t tell them, “Look, I never went to the labs,” so I had to pay them. But it sort of went on like that. I never really had an undergraduate degree. By the time I was—I started mainly taking a scattering of graduate courses without much background in them. I then was lucky enough to get a four-year fellowship, graduate fellowship, just did my own work and essentially never had—I never had much of a formal education.

It was—one of the greatest educations, educational experiences, I ever had in those four years was at Harvard. It was to have a desk in the stacks. In those days, the stacks were open, not anymore. A graduate student had a little desk in the stacks, and you had the whole of Widener Library, this amazing library, there. You can kind of walk around and pick things out from all kind of places, things you never heard of, and pursue them. That was a fantastic experience. I think it’s a great way to get an education.

And then I was, again, very lucky. I got to MIT, which is a research institution. They didn’t care what—didn’t care about credentials. You could work on what you wanted to. And it turned out very well. But it’s just a series of accidents. I think very few people are lucky enough to have an experience like that. So I’m not suggesting that you don’t go to college and do your work and get your degree.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: At the beginning of the film, Michel, you mention Manufacturing Consent, a film about Noam that came out in 1992. And I just want to acknowledge some people in this room worked very closely with Peter Wintonick, a great Canadian filmmaker, who made that film with Mark Achbar and who passed away this Monday—you know, a real loss for the documentary community. Noam, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about working with Peter and that film from—which must have started in the 1980s, really, and then came out in 1992.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, actually, I can’t really claim to have worked with—I spent a lot of time with him and enjoyed talking to him—very imaginative, thoughtful, dedicated person, who spent—really spent his life, not only then, but for many years afterwards, doing very admirable work of all kinds, often turned out in documentary films, but on serious issues which were hard to investigate. He was—did a lot of courageous, imaginative work. As far as that film is concerned, I had about as much to do with it as the moon has if people take photographs of the moon. You know, I was giving talks and giving interviews. And Peter and Mark Achbar was—I don’t know what you call him technically—producer or something?

ANTHONY ARNOVE: Mm-hmm.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Was—they’d come around and film, and we’d have some interviews, and they put it together. And I have to admit, I never saw it. I can’t stand watching myself, so I never saw the film. But I’m told it was a pretty impressive film, they did a very good job.

I know one thing that they did that I was very pleased about, was to take one issue that I’d been spending a lot of time working on, and it was a very difficult case. There were a small number of people working on it. None of us ever thought it would get anywhere. It was the case of East Timor, which maybe you know about, which was invaded in 1975 by Indonesia, with strong U.S. support. It led almost quickly to virtual genocide. I don’t like the term “genocide” much, but this one came pretty close, maybe 200,000 people killed out of a population of 600,000 or 700,000, all with full U.S. support. U.S. could have cut it off in two minutes. England, France, others also joined in to try to pick up a bit of the spoils. Indonesia is a rich country, lots of resources and a lot of incentive to support them. And there was very a small number of people who were trying to work on it, trying to bring some attention to it to see if something could be saved from the wreckage. Went on for a long time. Amy Goodman here was one of the people in 1991 who—she and Allan Nairn went and were practically beaten to death in a demonstration. They got—did some very good work and got some—a lot of important publicity. And now, finally, in 1999, President Clinton, under a lot of pressure, international and domestic, essentially called it off, with a phrase. He essentially told the Indonesian generals, “Game’s over.” They left. That’s what it means to be a powerful state. Now, there’s a lot to learn from that. But one thing I was pleased about in Peter’s film is that they emphasized this and did very evocative and imaginative work about it, which I think probably informed plenty of people about it. So it maybe saved a lot of lives.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: Michel, could you talk—I know tomorrow night the film opens at the IFC Center downtown. You’ll be there at 6:10, 8:15, after both of those screenings, also on Saturday. Could you talk about the wider plans and aspirations for this film?

MICHEL GONDRY: Well, I focused on Noam’s scientific approach. And I—it’s not that I dismiss the political work, and I’m aware that the goal is to save lives. And I think where people are too much talking about the past, and they sort of get—obstruct their view of what’s going on. I really understand Noam’s work into trying to basically save life and to acknowledging people of what is going on now. So—but I felt I could do a job into getting people to know Noam as a thinker, and maybe they would—especially in my country, where we have very little access to Noam, because—I think deep down it’s because you critique the media, and we have the news—I mean, the connection with Noam could—should be done by the media. But since they have been criticized, they pretend—and in France, we have to choose sides. So, basically, if you pick—if you don’t pick one side or—and they judge you from what—that’s what you call—you talk about with a pretense of—you know, there is all this thing in France with the Gayssot law, about—they don’t have exactly the same sense of freedom of speech as we have here. So, I thought that my people in France maybe would pay more attention to the political work of Noam if I would introduce—not introduce, but emphasize on the more scientific, unpersonal aspect.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: So, it’s—

MICHEL GONDRY: That was a little bit my goal. And, as well, I—as I said before, I’m very—to me, science entertains me much more than fiction, for instance.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: And, OK, so it’s coming out in France. How wide is the release here? I know IFC Films is bringing it out. Is it going to be on iTunes, Netflix? How are people going to be able to the film? How can people here help get the word out about the film?

MICHEL GONDRY: Oh, yes. I mean, you want me to advertise. Well, yes, go.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: I do, I do.

MICHEL GONDRY: See the film.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: This is the moment. And then we’re actually going to have time for, I think, around two questions from the audience. I wish it was more, but Noam literally has a flight to catch very soon. So—but, sorry, Michel.

MICHEL GONDRY: No, I—it’s going out, I think, in 10—I mean, gradually to 10 screens. And hopefully it’s going to go bigger. I mean, I don’t have any sense of how—how much it can reach. I never know in advance. But what I’m thinking is I do a—maybe do a contribution, and it could last, and in a few years people will learn about it, and it would still going—be going on. I remember the first time, when I showed the first half of the film to you, Noam, you said, basically, at the end of—I showed it to you on my computer, as you’ve seen the film—you said, “OK, I agree with it.” Basically, you were saying that you agreed with yourself, which I think is—which is great. And, to me, I mean, I understand what you meant, basically. It meant that—and I was very happy about it. It meant that I had not distorted what you were saying. But then you added, “But it’s going to take a few more generation for people to accept that,” talking about—still about generative grammar and the whole conception of the referential assumption, for instance. And I was telling you, “So you’re not upset that you won’t be here to witness that?” And you said, “No, I don’t care about that. What I care is like maybe nobody will be here because of the climate change and all the risk.” And I think it’s—I really wanted to add that at the end, but I didn’t do it. But I think it’s summarized Noam’s priorities.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: So, there are some audience mics, and I think there’s some people coming around. And there’s time for just a couple quick questions, maybe starting right there with the hat.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: How are you doing? Thank you both for your work, let me say. Noam, you went to a Deweyan school, and you talk about John Dewey often, or at least I—that’s—I see it online. I read about it. You, in many ways, whether you’d like to own that or not, are our modern-day Dewey, as like a leading social philosopher. I come from blue-collar background, and now I’m a Columbia student. And I often get, you know, the argument that, you know, we can no longer have these radical critiques, because we’re now part of this cosigning, contributing, co-opted entity that’s, you know, usurping proper education and indoctrination. How do you reconcile the two, being, you know, inside the system, part of the system, but also trying to change it and not be co-opted?

NOAM CHOMSKY: It’s always been a—first of all, I don’t—my own impression over 75 years of activism is that the level of energy and dedication and commitment, especially on the part of young people today, is as high as anything I can remember, outside of maybe a few very brief peaks, like mayb 1968, '69. But it's quite substantial. But you’re right that there are very intensive pressures to try to beat it back.

You used the phrase “indoctrination.” That’s actually the phrase that’s used at the liberal end of the spectrum, by those who are deeply concerned about the activism, independence, courage, great contributions of young people of the '60s, who really civilized the society. Right after that, there was a reaction, and across the spectrum at the sort of liberal end, the Trilateral Commission—that's basically Carter liberals; they staffed the Carter administration—a very important book, which called for trying to reduce—to introduce what they called more moderation in democracy, less participation. People should become more passive and obedient and apathetic. And as one Harvard professor there put it, “And maybe we can get back to the good old days when Truman was able to run the country with the help of a few Wall Street lawyers and financiers.” That would be democracy. But one of the things they emphasized was what they saw the “failure of the institutions”—I’m quoting—”responsible for the indoctrination of the young.” Schools, universities, churches, they were not indoctrinating the young properly. So, therefore, we have to do more to indoctrinate the young. And there’s been quite a—since that time, there’s been quite a campaign, from kindergarten to universities, in many different ways, to try to impose discipline, obedience, apathy, atomization, keep people separate from one another, all kinds of things. Those of you of that age have all been through it.

But you can struggle against it. And plenty of people are doing it, and there’s a lot that has been done. A lot more can be done. And I think there’s—I mean, what you mentioned is a problem, but I don’t think it’s a paradox. You can live—we do live within the society. We can’t pretend we live somewhere else. You can live within the institutions and work hard to change them.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: OK, we have time for one more question. A woman would be great. Yes, right there in back! Beautiful! Can someone bring a mic to the woman right there in the middle? Thank you.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Hi. First of all, it was really enjoyable, and you guys are such a great combination. I’m a huge fan of both of you. My question was for Noam about death. So, when I think about death, or when I think about life, really, because I don’t really think about death, I think that the thing that is alive in me is not behind my eyes, and it’s something that’s bigger than anything that I could ever possibly imagine. So, when you say this spark of—how did you put it?—this spark of consciousness goes, if you wanted to convince me that—you know, the way that you see it, like from dust to dust and then nothing happens, how would you explain that? Is that a question? How would you explain to me where that spark of consciousness goes?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, actually, that was my 10-year-old self. I did used to have nightmares about the idea that when I die, there is a spark of consciousness which basically creates the world. Is the world going to disappear if this spark of consciousness disappears? And how do I know it won’t? How do I know there’s anything there except what I’m conscious of? So if this spark disappears, it’s all gone. Later, when I got older, I thought that this is a rather classical concern, and a lot of thought and writing and agony and so on about it. But as you get older, you just realize that that’s not true. The world is going to go on. Your children will be alive, your grandchildren, your friends, other people’s children, the children of those villagers in Colombia who you saw there, and so on. And the world will go on. It’ll go on without me. But, OK, it went on for a long time without me, and a lot of it goes on without me, and that will continue to happen. It’s—it just seems like—to me, at least, it seems like less and less of a problem as you get older. It becomes easy to understand why this is really not something to be concerned about. My personal feeling.

ANTHONY ARNOVE: Well, on that very cheerful note, everyone, thank you to Michel Gondry and to Noam Chomsky and to DOC NYC for an amazing week of programming, to School of Visual Arts, to IFC, all the volunteers here.

Media Options