Guests

- Azadeh Zohrabia member of the Prisoners Mediation Team and the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity Coalition, and a Soros Justice Fellow at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children.

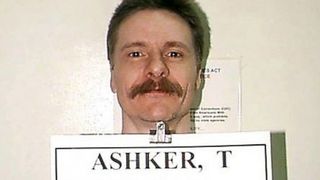

Days after a federal judge approved the force-feeding of hunger-striking California prisoners protesting long-term solitary confinement, we air an exclusive audio recording of a prisoner who has not eaten since the protest began on July 8. Todd Ashker, one of the authors of the call to hunger strike, has been held for years in the Secure Housing Unit at Pelican Bay Prison after he received a life sentence for killing an inmate in 1987. We also hear from California Correctional Health Care Services spokesperson Joyce Hayhoe, questioned by Democracy Now!'s Renée Feltz. And we're joined by Azadeh Zohrabi, a member of both the Prisoners Mediation Team and the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity Coalition, as well as a Soros Justice Fellow at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We end today’s show with an update on the prisoners in California who have entered the 47th day of their hunger strike to protest being held in long-term solitary confinement—many for a decade or longer. This week a federal judge ruled prison doctors can begin force-feeding some of those participating. We’ll get to that in a minute. But first I want to play part of an exclusive audio recording of a prisoner who has not eaten since the strike began on July 8th. His name is Todd Ashker. He was one of the authors of the call to hunger strike. He has been held for years in the Secure Housing Unit, or SHU, at Pelican Bay Prison after he received a life sentence for killing a prisoner in 1987. Ashker spoke to his lawyers recently over a phone line from behind a glass wall. It’s going to be hard to make out, but listen carefully.

TODD ASHKER: Greetings. My name is Todd Ashker, and I am from the Pelican Bay State Prison Short Corridor Collective Human Rights Movement. I am a principal representative of all similarly situated prisoners subject to long-term solitary confinement.

Our core demands are centered on: A, an end to indefinite solitary confinement based on innocuous associational behavior and/or confidential information intelligence from prisoners tortured to the point of serious mental illness and agreement to become state collaborator informants.

Additionally, CDCR’s STG pilot program is not responsive to our demands. It continues to base indefinite SHU solitary confinement upon confidential information intelligence without any requirement for any formal charge being filed and adjudicated for due process due to the California Prison System’s preponderance of the evidence standard.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Todd Ashker, a prisoner held in the Secure Housing Unit at Pelican Bay Prison in California, recorded by his lawyers, so it’s difficult to understand. And we want to play more of this exclusive audio.

At its peak, the California hunger strike included some 30,000 prisoners. Authorities say that, as of Thursday, 79 prisoners in four prisons remain on a hunger strike. On Monday, a federal judge ruled prison doctors can begin force-feeding some of the striking prisoners if they’re deemed incapable of making medical decisions. The order also allows prison officials to ignore the written directives of some prisoners who have refused such treatment based on claims the prisoners signed the “do not resuscitate” orders under coercion. For details, Democracy Now! producer Renée Feltz spoke to the California Correctional Health Care Services’ Joyce Hayhoe.

JOYCE HAYHOE: We’ve heard a lot over the past few days about force-feeding, and this absolutely is not force-feeding. It is introducing nutrition to an inmate that is to the point where they can’t talk to their doctor, where they’re unconscious, and the doctor is just following a normal community standard to keep that inmate alive, absent any directive that the inmate had previously put in place.

RENÉE FELTZ: And just to be clear, even if an inmate did put a directive in place, the judge’s order is saying that that could be overridden at this point?

JOYCE HAYHOE: If it was during the hunger strike, that is correct.

RENÉE FELTZ: What has actually occurred related to the judge’s order?

JOYCE HAYHOE: We wanted to have a proactive directive in place, so we don’t have any indication at this point, although, you know, that could change daily, but right now we’re not using the order to refeed inmates. There are inmates that are voluntarily choosing to come off the hunger strike and are starting to eat again.

AMY GOODMAN: That was California Correctional Health Care Services’ Joyce Hayhoe being questioned by Democracy Now!'s Renée Feltz. The reason for the judge's order, prison authorities say, is that some prisoners may have been coerced to sign their “do not resuscitate” order after they were pressured to join the hunger strike. They note that Todd Ashker, the prisoner whose voice we played, has ties to the Aryan Brotherhood, a white supremacist prison gang. This is California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokesperson Terry Thornton.

TERRY THORNTON: The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation have received evidence, intelligence, and inmates have told us, that they’re being coerced by gangs. Inmates are being coerced by gangs—not all of them, but some of them—to participate in this hunger strike. It should also be noted that the hunger strike leaders are all leaders of prison gangs, as well. This whole action, this hunger strike, which is the third one in the last two years, is being driven by gangs.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we go to Berkeley, California, where we’re joined on the phone by Azadeh Zohrabi, who is part of the Prisoners Mediation Team and the Prisoner Hunger Strike Solidarity Coalition, also a Soros Justice Fellow at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children, where she is focused on ending long-term solitary confinement.

Welcome to Democracy Now! What about the argument the prison is making, Azadeh, that they can force-feed, or they call it “refeed,” prisoners because they signed under coercion, because they were part of a gang, they argue?

AZADEH ZOHRABI: Good morning, Amy. Thank you for having me.

This force-feeding order and the story that the Department of Corrections is telling about this being coerced or this being a gang-related hunger strike is an attempt to depoliticize and delegitimize the reasonable demands of the hunger strikers. This has always been a voluntary and peaceful effort to create change around severe human rights violations that are happening in California prisons.

AMY GOODMAN: Azadeh, the whole issue of using the word “refeeding” as opposed to “force-feeding,” can you explain?

AZADEH ZOHRABI: Refeeding is just the process of introducing food back into the body after a long period of not having food. Right now, currently, there are people that have been refeeding. There’s people that have been coming off of hunger strike, mainly because—what we’re hearing from prisoners is that they’re not getting adequate medical care during the hunger strike, and they’re being told by medical staff that the only way that they’ll get adequate medical care is if they come up off the hunger strike. But refeeding is just the process of reintroducing food to the body, and so far it’s been done voluntarily by prisoners that are coming off the hunger strike. But as the court order says now, that the process could be forced for prisoners who are not—who are not willing to refeed voluntarily.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to play another part of the interview recorded with hunger-striking prisoner Todd Ashker, when he answers a question—again, it’s hard to understand, it’s through the phone, through glass, but we think that it is very important to hear these voices from behind bars—as he answers a question about how he’s evolved since he went to prison.

TODD ASHKER: Therefore, beginning in 2009, a group of us in the same pod together began considering our litigation strategies and how the challenges to long-term solitary confinement had not been successful. And over the next two years we all came to the conclusion that we needed to evolve our process of resistance and forcing change to the system. And during that process of dialogue with these individuals and the material that I was reading, including material about the IRA struggle and Bobby Sands, the Irish hunger striker who united the nation, Che Guevara, Howard Zinn, Naomi Wolf and other—Thomas Paine and other activists and revolutionaries, I became more class-conscious of the prisoner class as a microcosm of the working-class poor in this country, and that it was in our best interest to evolve our strategies and come together and utilize peaceful civil disobedience-type actions, in tandem with litigation, to try to force the changes that were long overdue. And that is how we came to the point of creating our formal complaint and then moving from there to the peaceful hunger-strike protest as a collective body.

AMY GOODMAN: That was prisoner Todd Ashker speaking to his lawyers recently over a phone line from behind a glass wall. One of the hunger strikers hasn’t eaten since July 8th. Very quickly, Azadeh—we have 10 seconds—the amount of time people are spending—Todd, among the many others who are protesting—the long-term solitary confinement. He was speaking from Pelican Bay. How long have people spent?

AZADEH ZOHRABI: There are people in California who have done 40 years in solitary confinement. That’s 40 years.

AMY GOODMAN: Forty years in solitary confinement. We’re going to leave it there, and I thank you so much for being with us, Azadeh Zohrabi.

Media Options