Topics

Guests

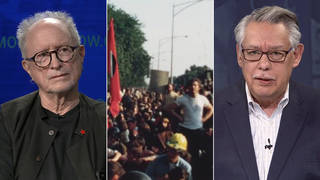

- Mike Gravelformer U.S. senator for Alaska from 1969-81. He is best known for his release of the Pentagon Papers into the public record. As a junior senator in 1971, Gravel insisted the public had a right to know the truth behind the Vietnam War. He then entered more than 4,000 pages of the 7,000-page document into the Senate record.

Watch part 2 of our conversation with former U.S. Senator Mike Gravel. In 1971, he entered more than 4,000 pages of the 7,000-page Pentagon Papers into the Senate record, insisting the public had a right to know the truth behind the Vietnam War.

Watch Part 1 of the interview and also see our interview with famed whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Aaron Maté.

AARON MATÉ: We continue our conversation with former Senator Mike Gravel. In 1971, he took advantage of congressional privilege to disclose the contents of the Pentagon Papers, that were then kept secret. Well, today, four decades later, former Senator Mike Gravel is among those calling on Senator Mark Udall to follow in his footsteps and enter the full Senate report on CIA torture into the Congressional Record.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Senator Mike Gravel joins us now from San Francisco. He represented Alaska in the U.S. Senate from '69 to ’81, most well known for releasing the Pentagon Papers into the Congressional Record, which meant then that they could be published in book form, available for anyone to read—though it wasn't quite that easy, actually. It was Beacon Press that published the Pentagon Papers, but they were under enormous pressure. They were being surveilled and monitored and harassed by the FBI for years before they published the Pentagon Papers. In fact, it almost brought down not only the press, but the Unitarian Church that runs the press.

But, Mike Gravel, we’re moving ahead here. We wanted to go back in time for you to tell the story of how you ended up reading or putting the Pentagon Papers into the Congressional Record. It’s an astounding story, starting with the editor at The Washington Post, Ben Bagdikian, pulling up his car at the Mayflower Hotel in the middle of the night to deliver the papers to you. That was part of the deal Dan Ellsberg had with Ben Bagdikian to give the Pentagon Papers to The Washington Post. He said, “You’ve got to get one copy to Mike Gravel, because he’s agreed to read them into the Congressional Record.” Can you take it from there, you and those Vietnam veterans that were protecting you and your staff, who couldn’t touch the papers, because you were afraid they’d be arrested?

MIKE GRAVEL: Well, actually, I didn’t really know what the legal consequences would be. This has never been done in American history. But we were resting on the speech and debate clause of the Constitution. And so, when Ellsberg asked me if I would use the papers, release the papers officially—and it was important for Ellsberg to have an official person release it; it would give him some legal umbrage. Now, so, I got the papers. We took them home after Ben Bagdikian had given them to me, and brought in staff, sequestered them in my home, so that we could read all of the papers to make sure that we weren’t acting irresponsibly. Then, after we did that, then I wanted—I was in the middle of a filibuster. That’s the reason why Ellsberg called me. And this filibuster—he asked me if I would read the papers as part of the filibuster.

Well, I was going to do that in the Senate, but unfortunately I made a mistake and put on a quorum call so that the staff of the Senate would be able to contact their homes and tell them they’re going to be all night, because Gravel is going to be reading something as part of his debate—part of his filibuster. And so, when I tried to pull back on the quorum, Michigan Senator Griffin objected, and I was dead in the water. We had to have a quorum before we could proceed. And the Republicans were telling their members to stay away from the Senate. We were trying to get the Democratic members to come back. Very difficult. And by 9:00, 9:30, it was hopeless that I would be able to read them into—which was my intent—into the Senate record.

But the attorneys that were advising me said that plan B, since I was the chairman of the Subcommittee on Buildings and Grounds, I could convene that subcommittee based upon the precedence of the House Un-American Activities Committee calling meetings on the fly as they went around the country to entrap people to testify. And so, we called a meeting, put the notice underneath the door. By this time, it was 11:00-ish. And we were able to get a congressman from New York, Dow, who came forward and testified. And so, I convened a hearing, and the congressman said he wanted a federal building in his district. And I said that, “Well, I can appreciate that, and I’d be happy to give—authorize building a federal building in your district, but we don’t have the money. And the reason why we don’t have the money is because we’re squandering it in Southeast Asia, and let me read something about how we got into that mess.” And so I proceeded to read the Pentagon Papers.

I had not slept, essentially, for three days. I really was scared stiff, because I didn’t know the consequences on myself as to what I was doing. And so, I broke out emotionally and was sobbing, got control of myself and then did the obvious thing, which was to ask unanimous consent to put it into the record. And, of course, since there was no one there to object, I said, “It’s done.” And that put the documents into the record of the subcommittee, which is a record of the Senate.

Now, what we have with the torture report, this is something that is already in the record of the Senate, because it’s in the record of the Intelligence Committee. And they did redactions, and they did research. And so, it’s there. It doesn’t have to be re-entered into the record—it’s there. What it needs to do is to now be put out publicly so that the people in the media and the people can do the research that’s necessary in these 6,000-plus documents. And the simplest way to do that is for a member of the Senate or the House to take their hands—take this document, put a press release explaining what they’re doing and how important it is for a democracy for the people to know what their government is doing in their name, and then take this document to the press room of the Capitol and start handing it out to various members of the press.

But that’s exactly what we did. After I turned around and put it in the committee record, we went back to our offices. We copied the Pentagon Papers and handed it to reporters, who created a pool and then distributed it. So the key was to be able to distribute it to the public, and so—and not just my release of putting the papers in the committee record, it was the physical act of releasing it to the public that counts. And so, now what applies with today is the simple act of taking this record that’s there, explaining why you’re doing this—to save our democracy—and hand it out to the public.

AARON MATÉ: So, Senator, the—

MIKE GRAVEL: It’s that simple.

AARON MATÉ: So, Senator, the lawmaker who you’re calling upon to do this is Senator Mark Udall. And your experience as chair of a subcommittee, a chair—as the chair of a subcommittee, is relevant to Udall, because he also chairs a subcommittee. Is that how you want to see him enter this report into the record?

MIKE GRAVEL: No, I think it’s easier than that. He’s chair on a subcommittee on, I think, the Armed Services Committee. But it’s easier than that. Stop and think. We are resting on the words of the Constitution of the United States, which say that a member of Congress can release whatever he feels is necessary for the edification of the electorate. And he can’t be questioned or prosecuted in any other domain after he’s done that. And it’s an absolute rule. And this was sustained by the unanimous decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. Now, the majority of the court did not agree with my ability to publish it with Beacon Press, but they did agree, just easily, with the interpretation of the Constitution that speech and debate is the basic and most important activity of our government to the people. Otherwise, how are the people ever to react to what the government does, if it’s all held in secret?

Now, with respect to Senator Udall, I’d be prepared to go to Washington and help him physically do this. I’ve got no problems with that. This is fundamental to a democracy. If the people are not informed as to what their government is doing, then you do not have an operational democracy. And that’s the situation we find ourselves in today, in the expansion of secrecy, not only within the military, but secrecy within the Congress itself. They all buy into this and don’t realize that their most important obligation under the Constitution, which they swear to when they swear—when they’re sworn into office, is to defend this country and to defend this Constitution from inside the government and outside the government.

AMY GOODMAN: Senator Gravel, have you spoken to Mark Udall?

MIKE GRAVEL: No, I haven’t. I had a situation earlier this year where Senator Wyden was going to call me, and, of course, he didn’t. And it was on this subject. And so, I felt—

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, it doesn’t just have to be Udall. You’re saying Udall, as he’s the outgoing senator. But why not, for example, Senator Wyden?

MIKE GRAVEL: Yeah, there’s no risk at all. There’s not even political risk, because he’s stated on the floor, and privately, that he would like to spend a major portion of his time out of office going after this secrecy problem and going after torture and revealing that. Well, the best way to do that right now is to reveal the entire study before January. In that way, he can mine that, and so can scholars and reporters mine it throughout. Keep in mind that Snowden made moot the issue of members of the Intelligence Committee releasing what the NSA was doing. But they knew it. They talked about it internally. But they never said anything about it publicly. And the only thing that binds them is peer pressure. Now, when the Republicans say they’re going to stop them, they can’t—unless you could physically assault them, they can’t stop them.

But the key is to get the document and hand it out to the public. He’s got the right to do this under the Constitution of the United States, which has been sustained. That action has been sustained by the unanimous agreement of the Supreme Court of the United States. And so, that’s the Constitution, case law of the Supreme Court. There’s no risk in doing this. But there’s also much to be gained from it, because then we can begin to hold elements of our government accountable for the unbelievable debasement of our morality.

AMY GOODMAN: Senator Mike Gravel, we want to thank you for being with us, former U.S. senator for Alaska from '69 to ’81, best known for releasing the Pentagon Papers. As a junior senator in 1971, he insisted the public had the right to know the truth behind the Vietnam War. Though the Pentagon Papers had been written about by The New York Times and The Washington Post, he wanted to ensure people had access to the full secret history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, and so he put thousands of pages of that report into the Congressional Record. They would eventually be released by Beacon Press. I'm Amy Goodman, with Aaron Maté.

Media Options