About a month after the death of Mario Savio, we feature a 1994 speech he made about the roots of the Free Speech Movement and its relevance to the current struggles, and play excerpts from speeches at his memorial by Jack Weinberg and Bettina Aptheker. Weinberg recalls the roots of Savio’s work in the civil rights struggle, particularly his participation in Freedom Summer, and reflects on the victories won by the Free Speech Movement. Aptheker remembers Savio’s integrity, humanity and commitment to collective struggle.

Transcript

BETTINA APTHEKER: Free Speech Movement shaped Mario at least as much as he shaped it. Ours was a movement of collective strength, of a fledgling wisdom nurtured in each other. The media, in its rush towards idolatry, has never understood this. Mario would also be the first to tell you that it was the Black students in SNCC, the Black sharecroppers in Mississippi, the Black women, like Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, that moved him so and that inspired the white students of our generation to push ourselves up and out into our own humanity.

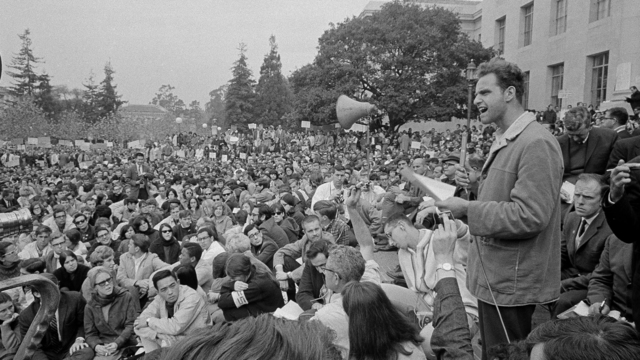

LARRY BENSKY: Mario Savio would have been 54 years old yesterday, December 8th, 1996. Mario Savio passed away just a month earlier, November 6th. Yesterday, in UC Berkeley’s Pauley Ballroom, just a few yards away from the scene of his great fame 32 years ago on the steps of the University of California administration building Sproul Hall, a memorial service was held for Mario Savio, outstanding spokesperson for the Free Speech Movement. There were 17 speakers and over three hours of ceremony before a packed audience of more than a thousand people. Afterward, the people in thew audience went across the street to the steps of Sproul Hall to sing “We Shall Overcome.” We begin this commemoration of Mario Savio and this report of yesterday’s event by listening to a speech by Mario Savio just two years previously on the commemoration, the 30th anniversary commemoration, of the Free Speech Movement, the fight to allow political speech on the University of California campus, for which Mario Savio was an outstanding spokesperson and with which he will always be identified. Mario Savio, speaking December 6th, 1994, on those same Sproul steps.

MARIO SAVIO: Thirty years ago — and I think we are closer to you now than we were then to the people who struggled during the ’30s — but 30 years ago, a long time, one generation, a little bit more, we were awakened from our dogmatic slumber by a clarion that was sounding off the campus. It really was in response to and in participation in the civil rights movement that this all got started.

We had a lot of things to learn. We had to learn about race. We haven’t learned that completely yet, have we? But we’ve made progress, all right? We needed to learn about race. We needed to learn about our relationship to the planet. We haven’t learned that completely yet, but we’ve made a lot of progress. We needed to learn about gender. We haven’t learned all of that yet, but I think we have made a lot of progress, although I was at a meeting last night. There was a woman who got up to speak. I thought she was misguided. She was greeted by jeers and scorn. And those were the jeers and scorn of men, I have to say. So, we haven’t learned it all, but we’ve had a lot to learn, very deep lessons.

And it’s taken a long time. In fact, it’s taken our community 30 years to mature. Thirty years to mature. That’s what’s been happening. And they say, “Well, OK, the other side has won.” Well, they’ll get their squalid little footnote. Meanwhile, we’re building a community. And it takes a long time, because it’s a community built on deepened consciousness, not mania and the fabrication of enemies. And that takes time. It’s taken us 30 years.

We had to do other things, too. We had to learn how to make a living. I teach up at Sonoma State. Well, if you call college teaching work, I work. All right, now, we also had to raise children. It’s one generation that’s passed. We had to find ways to do those things while exploiting our fellows as little as possible. It has been very, very difficult. Very difficult, indeed. And those are hard lessons to learn.

I teach a course at Sonoma State, “Science and Poetry.” It’s a seminar. And we were just coming to the end of “Burnt Norton.” That’s the first one of Eliot’s Four Quartets. And this is the passage. And I realized it could be about us:

Sudden in a shaft of sunlight

Even while the dust moves

There rises the hidden laughter

Of children in the foliage

That was us. We were those children.

Quick now, here, now, always—

Ridiculous the waste sad time

Stretching before and after.

One of the students said, “Well, you can’t recreate the past.” And I assumed he was talking to me personally. So, so, I hope you will feel that I’m not completely insincere if I do try to redeem some of that time by noting that I once again hear a clarion off the campus. Once again, I see a society in crisis. OK? That crisis is a deep one. That crisis goes to the way people work and don’t quite make it when they work. Our secretary of labor, or yours or whoever it is — right? — Robert Reich, described an anxious class. Well, of course, he’s talking about the working class. Described an anxious class consisting of millions of Americans who no longer can count on having their jobs next year or next month, and whose wages have stagnated or which have lost ground to inflation. They’re afraid. They’re frustrated. They’re anxious. They are the people who voted in the last election. They are the people who voted in the last election, not mean people, but frightened people, people who are anxious, people who see their lives slipping away, who work and don’t see what they’re working for, people poorer than their parents were. All right.

Why is this happening? There are a number of reasons, but I want to point to one that I think is very important, because it’s going to be with us for a long, long time. We, as a nation, are in competition with other nations which pay their workers much less than our workers are used or have been used to receiving. That’s good, my friends. That’s good because we want to spread the possibility of being wealthy very broadly over the entire planet. However, there will necessarily be a period of transition. That kind of competition inevitably exerts a very steady and harsh downward pressure on American incomes. The question is: Whose incomes? OK, that’s the thing to think about.

You know, we have those who have and never lose, and others who just barely make it. If you check the stats — and you can do it, OK? You could look it up, as they say. If you check the stats, you’ll see that the rich have maintained their incomes. The middle class, so-called — the workers, in other words — the rest of us, have gradually lost ground. That is going to continue because it’s the whole world that’s going to want to become wealthy, right? And therefore, we’re going to be in competition with that whole world for a long time.

So, the question is: How do you spread the pain here in this land of wealth during this period of transition? Well, naturally, naturally, the wealthy don’t want us to spread the pain to them. I mean, that makes sense, guys, OK? The wealthy do not want us to spread the pain to them. OK. Therefore, they want us to enter into a coalition with them against the poor. We’ll make the poor suffer. Then you’ll know that you’re not as bad off as they are. You won’t feel so bad, even though you’re suffering a great deal yourself. OK, that kind of coalition, that’s old. They try to do that all the time. But now they are getting somewhat desperate. And when, in order to consolidate that coalition requires getting people to believe the unbelievable, not to turn and say, “Hey, you guys have to suffer along with us,” but, no, take it from them, and they have nothing, right?

OK, under those circumstances, the political class resorts to obscure, obscurantist and, finally, very illogical argument. And what is the nature of that argument? Find enemies. Find enemies. It’s the logger mentality. Circle the wagons. Who’s inside? Inside are the normal Americans. The normal Americans are scrubbed white, 100% Christian and mostly men. Those are the normal Americans. Outside, whoever we can take it from, whoever we can shaft. Lots of enemies. If people are afraid of enemies, the aliens amongst us, if people are afraid of enemies, they won’t analyze the problem in its own realistic terms.

My friends, that is — I’ll say “my friends.” I used to say it all the time before. That is the problem with Proposition 187. It is creeping fascism, creeping fascism. Don’t get the wrong idea. This isn’t, you know, exotic, pretentious, intellectual, European fascism. This is American know-nothing fascism. OK? And they aren’t all — and they aren’t all fascists. You know, you have the Gingriches and the Helms. OK, crypto-fascists. But, mind you, mind you, you have Pete Wilson. He’s just an opportunist. But look at the opportunity he’s taking. He’s taking an opportunity based upon demonizing human beings in our midst in order to get first to Sacramento, second time, and then maybe to Washington, a very serious kind of opportunism. And we need to stop it.

Now, I want to tell you, they don’t have such a strong hand. They wouldn’t be doing this if they had a strong hand. They don’t have such a strong hand. Here is why their hand is weak. This contemptible little law, if it gets out of the courts, depends for its effective enforcement on the willing and conscious cooperation of doctors, lawyers, social workers, teacher, librarians and students. And most of those people were against it. And at least some of them can come over to an in-their-faces campaign of systematic noncompliance.

I suggest something as — not as the only thing, as one possibility in addition to everything else, if it comes out of the courts, something on the order of the old War Resisters League, OK? You research. You find out how this law impinges directly on every class of people, on students, on workers, on teachers, everyone you can speak to, OK? You offer them counseling. Don’t tell them to break the law. Invite them, though, to be counseled. Tell them what their options will be. If they decide to break the law — that is, if they decide not to cooperate — you provide them with the lawyers. You provide them with the publicity. Don’t let any act of conscientious objection to class war, which is what it is, my friends — don’t let any act of conscientious objection, their precious acts, go in secret. This is not hiding your light under a bushel. If the person has to go to work and say, “I won’t cooperate,” go with that person. Support every person who’s willing to take a risk.

I just want to sum — I just want to conclude by referring to two other poets. I love poets, guys. Love poets. OK, two other poets. Yeats, OK? Yeats. Here’s the situation. Yeats, OK.

everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Don’t let it be so. Don’t let it be so. They don’t have the passion. We have the passion. They have mania. OK? We have the passion because our community is a community of compassion. We want to relieve suffering because we feel that suffering. The only thing they can do is make other people suffer.

The second poet, José Martí.

Con los pobres de la tierra

Quiero yo mi suerte echar.

With the poor of the Earth, no matter what side of the border they’re on, whether they’re legal or illegal, with just folks, folks whether they’re Black or Brown, folks whether they’re yellow or red, folks who wear pants, folks who wear dresses, folks who wear both, for God’s sake, we want to cast our lot with the people, not with the bosses. We don’t want to buy into that coalition against the poor. Do it! Do it!

LARRY BENSKY: The late Mario Savio, speaking at the 30th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement in December of 1994. In a moment, we’ll hear excerpts from remembrances and commemorations of Mario Savio as yesterday’s observance in Pauley Ballroom on the University of California, Berkeley campus. This is Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! I’m Larry Bensky. We’ll be back in 60 seconds.

[break]

LARRY BENSKY: You’re listening to Democracy Now! I’m Larry Bensky in Berkeley, California, where yesterday a commemoration of the life of Mario Savio was held in Pauley Ballroom on the UC Berkeley campus before an overflow crowd of more than a thousand people. Mario Savio, spokesperson for the Free Speech Movement, which began in the fall of 1964, was remembered by several of his Free Speech Movement contemporaries, who were quick to point out that it wasn’t the Free Speech Movement itself on the University of California campus that ignited sui generis. It was in fact a result of the civil rights movement, especially Freedom Summer, that had taken place in the summer of 1964 in places like Mississippi, where Mario Savio had taught in a Freedom School.

Jack Weinberg was one of those who remembered Mario Savio, Jack Weinberg who himself became famous having been imprisoned in a police car for over 40 hours when demonstrators wouldn’t let the police drive him away. Weinberg had been arrested for distributing literature for the Congress of Racial Equality on the campus. At that time, University of California rules forbade the solicitation of funds or the distribution of literature for off-campus organizations on campus. It was a demand for free speech in that realm that led the Free Speech Movement to begin. Jack Weinberg remembered the roots of the Free Speech Movement in the civil rights movement in the South, and especially the murder of the three civil rights workers, Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman, in the summer of 1964, something Mario Savio knew well, as he was working just a few miles from there. Jack Weinberg.

JACK WEINBERG: The reason why there was a mobilization of young people going into the South that summer was not primarily because they had organizing knowledge or experience. The reason was that there was such a wave of violence and repression and murder preventing organization to go forward that young people from elite centers of universities and privileged parts of society went down to the South to bear witness to that and to make organizing possible. And so, their murder, while it was a tragic and shocking event, was also, in many ways, a predictable event and brought light to the facts that were happening. And I think the important thing to note was virtually none of those young people — and that happened right at the very first week of the summer project, and those young people did not turn tail and run, but stayed there throughout the summer and continued the project.

So, Mario went through that experience. There were many of us here in Berkeley, a lot of direct action going on. There was a Democratic Party convention. There was a Republican, but there was also a Democratic Party convention that summer. And there was the expectation that the culmination of Mississippi would come to the Democratic Party convention, and the racist, segregationist banning — the Democratic Party of Mississippi, that did not allow Black people to be part of the primary process, was having its delegation challenged, its credential challenged, by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. And that was going to be the culmination of the project.

It was a huge shock to all of us when the liberal wing of the Democratic Party, led by Hubert Humphrey and others, rejected that. Instead, it was the first sense of real betrayal. We were a movement that was winning, that had the moral high ground, but then there was this huge sense of betrayal. And then we came back to the university, and the university betrayed us again. Rather than being proud of what their students were doing, it tried to suppress them.

And when it did that, and when it initiated rules, under pressure of the business community, to keep students from this university from mobilizing to take part in the activities of their day, and the students said no — and Mario was the leader, and he was the leader, and he was the symbol, and he was the spokesperson, and he was articulate not because he was inherently articulate, but he was articulate because there was a funnel, and he was the top of that funnel, and he could listen, and he could hear, and he was expressing a voice not of his self, but of a whole collectivity. And the students rose up and told the university they had no ability to stop us from engaging in society. It was a large uprising. We won. We established those rights. Mario was in the leadership of that. And the significance of that is profound, because that fight on the Berkeley campus was a fight that did not then have to be refought in detail throughout American society. Students had won the right — and that was contested until that point — students had won the right to engage in the politics and protest of outside society as students. That was won in 1964. And that was very important.

And the reason it was important, among others, is, in 1965, when the War in Vietnam escalated — a lot of people look back at the War in Vietnam, and they talk about, “Well, antiwar movements, we know what they’re like.” But in '65, looking forward, there had never been a war in America or, to my knowledge, worldwide where a government at war tolerated protest movements at home. And so, when the war was escalating, and the Berkeley students had just won the right to protest, and it was the War in Vietnam that was the vehicle that was being protested, that was the moral outrage. And there was not the will in the repressive apparatus as a society to nip that in the bud. So a mass antiwar movement was given birth because of the victory that had just been won. And so, we won the right to protest war, as well as the right to participate in the civili rights movement. And that was the event that started the 1960s, the protest generation of the 1960s, that made it possible — that made it impossible or very difficult for the powers that be to suppress citizen democratic speech, protest movement. And that was a victory, and Mario was at the centerpiece of that victory. And that's why we’re all here to celebrate them. And when the media asks, “Why did so many people come out?” I think that’s the reason why so many people are here today. Thank you.

LARRY BENSKY: Jack Weinberg, speaking at the commemoration of the life and works of Mario Savio yesterday on the University of California campus. Another speaker and longtime friend and associate of Mario Savio’s is Bettina Aptheker. Aptheker was somewhat anomalous in the Free Speech Movement. The administration of the University of California and the red-baiting newspapers in the San Francisco Bay Area repeatedly called the movement communist. There were very few, if any, communists in the movement other than Bettina Aptheker. It was a dangerous thing to be in those years, because you risked a prison sentence. It was a felony to be a member of the Communist Party up until 1966. Bettina Aptheker was the daughter of the noted Marxist theoretician Herbert Aptheker. She spoke movingly of her friend Mario Savio yesterday.

BETTINA APTHEKER: Mario’s great strength as a student leader was his absolute and transparent integrity. He never wavered from the bedrock of his principles: freedom of speech, justice and equality. He was never beholden to any political party or ideology. He spoke only from his own conscience. He believed in the intelligence and goodwill of his fellow students. He was not interested in personal power. He told everyone everything that went on in administrative and faculty meetings.

The Free Speech Movement shaped Mario at least as much as he shaped it. Ours was a movement of collective strength, of a fledgling wisdom nurtured in each other. The media, in its rush towards idolatry, has never understood this. Mario would also be the first to tell you that it was the Black students in SNCC, the Black sharecroppers in Mississippi, the Black women, like Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, that moved him so and that inspired the white students of our generation to push ourselves up and out into our own humanity. But much of the press — but much of the press — much of the press, even as it has generously and genuinely mourned Mario’s death, continues to mount him as the icon of student activism, thereby once again erasing the suffering, the poverty and the racism against which he so courageously and selflessly struggled his entire life.

Mario had about him an unutterable sweetness, a tremendous passion, a selfless compassion. I remember in one of his speeches — I think it was in 1984 at the FSM’s 20th anniversary noon rally — he spoke of the Jewish Holocaust, of the pictures of the survivors emerging from the concentration camps. When he saw those pictures, he said, he thought the world would change, that the world would surely change, that never again would we permit such an unspeakable genocide against any people. But we were wrong, he said. Mario was appalled by injustice — I mean personally appalled. He was incredulous when he encountered meanness, selfishness or jealousy in people, because these were emotions and ways of being that were so foreign to him.

Mario was a brilliant thinker, interested in physics and astronomy, a magician in formal logic. Above all else, Mario had a vast personal courage. Life was not easy for him. There were economic hardships and complicated moral judgments, serious internal conflicts and emotional upheavals. In the midst of these realities, he walked through the world committed to changing it and to changing himself — the most difficult of tasks. However great Mario’s personal courage, it was also Lynne who chose to provide the bedrock that made his life possible, and it is Lynne’s courage and her compassion and unconditional love that moves now in the world, a gift to all of us who live. How we embrace you!

Mario’s life was a search. It was a practicum in search of meaning, in search of wholeness, from politics to philosophy to logic to physics to astronomy to healing to meditation. It was personal. It was political. It was spiritual. He was, in the words of the Buddha, “a lamp unto himself.” His search was not a linear progression, which does not exist in any event. No, for Mario, each search, each understanding, each dimension circled back into the others, layering, honing, softening a mind already so flexible and wide.

Mario saw the suffering, felt his own suffering and the suffering of the world. He believed that beyond this suffering there was hope, and beyond hope there was struggle, and beyond struggle there was community, and beyond community there was justice, and beyond justice there was redemption, and beyond redemption there was freedom. His search led him towards that freedom as it encompassed and was born of suffering, hope, struggle and justice. His was a deeply personal quest and a deeply spiritual one. This was a freedom beyond the conventional understanding of the word, a freedom that included the political but went beyond it. It was a freedom of mind, a freedom that saw reflected in the human mind the vastness of ocean, the vastness of sky. He had the idea, near the very end of his life, that perhaps mind, resting in this spaciousness, could extend itself into a perfect tranquility and joy.

The house which Mario and Lynne had just bought — their first — is high up on a hill. From its living room windows, facing east, there is a gorgeous view of valleys and trees, mountains and sky. Mario said he had never had a home with any real view at all. He so looked forward to this one.

Mario loved the wind. He loved water. He loved mountains. He loved the night sky. With each breath, he was connected to all of life. Mario, with each breath now, as we breathe for you, and together we will look, watch, gather ourselves together. We will move towards the sighting that was on the horizon of your life, hold you in memory and walk with you, holding each other in our grief, until dawn. Thank you.

LARRY BENSKY: The capacity audience at Pauley Ballroom walked a few short yards across Sproul Plaza yesterday to the steps of Sproul Hall, where Mario Savio had spoken so many times in the Free Speech Movement and afterward. The last speaker we heard was Bettina Aptheker. A fund has been set up for the family of Mario Savio, and another fund has been set up in order to endow a lectureship in his name on the University of California campus. If you’re interested in either activity, you can contact Jack Kurzweil at area code 510-548-7645. That’s 510-548-7645. Or write to him on email at jkurz@igc.apc.org. The commemoration of Mario Savio’s life is available on tape from the Pacifica Archives at 1-800-735-0230, as is this broadcast. I’m Larry Bensky for Democracy Now! in Berkeley, California. Back to Amy Goodman in New York.

AMY GOODMAN: And thank you very much for that, Larry. The music in our Mario Savio segment today was performed live by Country Joe McDonald at the Berkeley memorial service yesterday. And we had production help in Berkeley from Andrea Kissack, Michael Yoshida and Jim Bennett. Well, it seems that students are protesting all over the world, students here in New York around Mumia Abu-Jamal today down on Wall Street, and there are student protests in Burma, in Hebron in the West Bank, in Serbia, in East Timor. Tomorrow is International Human Rights Day. It’s also the day the Nobel Peace Prize winners will receive their award in Oslo. José Ramos-Horta and Bishop Carlos Ximenes Belo are both struggling for freedom in their homeland, East Timor. And in honor of this day, tomorrow we’ll bring you a special, a documentary called Massacre: The Story of East Timor, and it is updated to include the special Indonesian connection that President Clinton has. Also, later in the week, we’ll be looking at CIA involvement in Burma, and we’ll be looking at anti-Disney week. If you’d like a copy of today’s show or a copy of any Pacifica program, you can call to order from this number, 1-800-735-0230. That’s 1-800-735-0230. Democracy Now! is produced by Julie Drizin. Our engineer, Errol Maitland in New York. Help from Kenneth Mason in Washington. And you can call our comment line at 1-202-588-0999, extension 313. That’s 202-588-0999, extension 313. I’m Amy Goodman, for another edition of Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! Thanks for listening.

Media Options