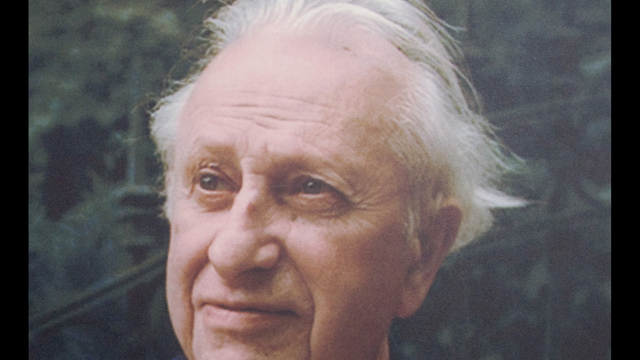

We are joined in studio in Chicago by the legendary radio broadcaster, writer and oral historian, Studs Terkel. He speaks about conventions, the real difference between Clinton and Dole, big government, Chicago ’68, Chicago ’96, FDR, Nixon, the perversion of language, and much more. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: And welcome to our last second hour of Democracy Now! from Chicago, covering the Democratic National Convention from the inside and the outside. I’m Amy Goodman, with Salim Muwakkil, senior editor at In These Times based here in Chicago and also a columnist with the Chicago Sun-Times. Coming up in a little while, you’re going to be hearing some of the sounds from outside. Yes, the sounds from the protest pen, poets speaking to the delegates, but speaking to each other. And interestingly enough, the largest audience there was the police that surrounded them. But right now…

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Right now we’re privileged to have in our studios a man who virtually embodies Chicago, a living legend, author of nine books, including one that has my story in it.

STUDS TERKEL: Sure does.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Studs Terkel. Studs, thank you for joining us. We are absolutely privileged.

STUDS TERKEL: Thank you. I like your style, Salim.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: OK, thank you, sir. Studs, since we are talking about the conventions and whatnot, you’ve seen quite a few of these conventions come and go.

STUDS TERKEL: Mm-hmm.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: And in Chicago, which is the convention city, you’ve seen them.

STUDS TERKEL: Mm-hmm.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: What are your some—what are some of your immediate impressions?

STUDS TERKEL: Well, this is of course—this one is bland and programmed as much as the one in San Diego was. The difference is one slightly of substance, because the supporters of Clinton are somewhat different than the supporters of Dole. However, we’re talking about two empty vessels, really, aren’t we?

SALIM MUWAKKIL: We are, indeed.

STUDS TERKEL: The real difference between Clinton and Dole can be poured into Tom Thumb’s thimble, and you still have a little space for a small martini. But basically, there is a slight difference. The supporters, of course, are those we know, and a lot of them we admire, and some just hacks. But the fact is, there are some differences. So, the questions is—the usual question—we’ll come to the conventions—do you vote for the lesser of the two evils? Michael Moore, in the current edition of The Nation, speaks of the evil of the two lessers, you know? And then there’s the question long ago offered, the challenge and a question: I would rather vote for something I want and not get it than vote for something I don’t want and get it. And how often do we go with the—how often will we go along with the lesser of the two evils?

SALIM MUWAKKIL: That’s all we—that’s all we’ve been able to do thus far. And speaking of what we voted for and got, we’ve gotten Clinton, and now—and we also got Dick Morris, who was recently—

STUDS TERKEL: Now you raise an interesting—here, they say it’s a scandal. What is so scandalous about one whore visiting another? No, think about it now. I mean, I know it’s a harsh phrase, but he is for hire. He works for a troglodyte, like Jesse Helms and other such, and, without blinking an eye, works for seemingly enlightened Clinton. And he’s the one whose advice Clinton took when he signed the death warrant maybe for—I don’t know how many poor kids. He removed—he tore away, in what is called the “welfare deform bill,” or whatever it is—and he tore away the safety net for the most vulnerable of our species—poor kids—that’s been there ever since, I’m old enough to remember, the second inaugural address of Franklin D. Roosevelt, when it began. “I see one-third of a nation ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed.” And then came the WPA—government, big government.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: This is the beginning of the big government that Republicans are castigating.

STUDS TERKEL: Big government stepped in, and there was the WPA. “Harry had jobs,” provided the PWA of Harold Ickes, I suppose the grandfather of the adviser who was ignored. The Resettlement Administration, which poor farmers and sharecroppers got a chunk of land, under Rex Tugwell. All were attacked at the time, but that provided—became the safety net for the most vulnerable. And that’s removed by a Democratic president—and at the advice of Dick Morris. And now he comes—so we have a case of someone who is, you might say, a high-priced, upscale call boy visiting a more modestly priced call girl. What it mostly provides for us is what? It’s a metaphor, a dreary metaphor for our whorish times. Let’s face the reality, the harsh reality, of it. And that’s what it’s about. So that’s no scandal. The scandal is, of course, the measure that Clinton signed.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: It couldn’t have been put more appropriately—a metaphor for these whorish times, indeed.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Do you see any chance that we’ll be emerging from these whorish times?

STUDS TERKEL: Well, I suppose—the other day, I ran into, by accident, Wellstein, Senator—

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Wellstone.

AMY GOODMAN: Wellstone.

STUDS TERKEL: Wellstone, Paul Wellstone of Minnesota, the one senator with guts up for re-election who voted against it. He feels fairly hopeful. The implications are that Clinton will win and that there’s this whole group, the Black Caucus, will now—

SALIM MUWAKKIL: The Progressive Caucus.

STUDS TERKEL: —will now put his feet to the fire. And so, he feels sort of hopeful in that sense. And naturally, I hope he’s right, and I admire him very much.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, Studs, I was saying to all those Democratic Congress members and delegates, who continually repeated that refrain, so I think it was put out from the administration, “We have to re-elect President Clinton because he did sign this welfare repeal bill.” And I say, “Wait, what are you saying? Because you’re against it?”

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And they would say, “Because if we re-elect him, and if we have a Democratic Congress, he can change some aspects of the law.”

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, it’s—

AMY GOODMAN: But I say, “What if he’s not re-elected? What is the legacy he leaves this country?”

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, but for the moment, just assume re-election, and come to your other question, what if he’s not. Then he’ll reform it. It’s like someone signing a death warrant. Whoever it is is dead, and the guy says, “Look, don’t worry. I’ll revive him.” In a sense, it amounts to that. Now your other question—so, ask Salim, and then I’ll try to think about it. What if—

AMY GOODMAN: Well, the whole idea that they’re saying—they’re sort of holding the population hostage—

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —saying, “OK, we signed this. If you put us back in, we will change it.” Well, what if the voters don’t put him back in? Then he leaves with his administration as having removed 60 years of federal assistance for the poor in this country. You’re listening to Democracy Now! And I do want to say, it’s a great privilege to have you in our—actually, in your studio, Studs—

STUDS TERKEL: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —because we’re reporting here. We’re in Chicago just visiting, although Salim lives here, after especially your—you know, you went through—what was it? A quintuple bypass surgery?

STUDS TERKEL: Oh, yeah. Well, it was a medical adventure. And I’ve lost about 20 pounds, so I’m in the fighting weight: 135. I can take on all comers, lightweight division.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Well, you really look good. You look revitalized.

STUDS TERKEL: Lightweight division, yeah. I’ll fight Battling Nelson. He won the lightweight title in 1908, and I’ll meet him just as he is today.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: A lot of people tried to compare the Chicago of ’68 to the Chicago of ’96. What differences do you see between the two Daleys, the father and son?

STUDS TERKEL: Well, the times have changed. The city has changed. Remember, when the elder Daley was there, he had far more clout than his son has, because he held a people, the African-American people, hostage, because they had an overseer.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Dawson.

STUDS TERKEL: His name was Bill Dawson. And Bill Dawson was the most powerful black man in America, because he controlled the plantation, as it was, really. Now, the plantation days are over. There is a great deal of bewilderment now in the black community, as there is everywhere, and as one or another pushing around one way or another, trying some [inaudible]. And Harold Washington, of course, was a marvelous moment—best mayor Chicago ever had. And he was a mayor, by the way, who—can you imagine a Chicago mayor who read books? And he did all the time. But coming back to Chicago then and now, it’s altered. He’s considerably different. There are certain amenities he does observe that the old man didn’t, certain civil—that he has to. So, in that sense, it’s different, because no longer is the plantation here. The machine creaks along in its own way, and of course he has his own sort of clout. But in a general sense, whether he helps the city—to some extent, but the difference is one of the city, a time rather than a person.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Mm-hmm.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, I wanted to go back even before Richard Daley Sr. You were just mentioning FDR’s second term and when he made that speech, when he instituted welfare as we know it in this country—or, I should say, as we knew it. Let’s go back to that time and talk a little more about it.

STUDS TERKEL: But a hair. Let’s not glorify FDR, either. He was, well, my favorite president, of course, by far the best of our century, by far. However, it was bottom-up pressures. There was a Great Depression. There were all sorts of grassroots things happening on the streets. You know how Social Security came into being? He wasn’t for it himself. He didn’t—remember, his first term was a budget-balancing term—meant nothing. The second term, there was so much pressure from below. The various groups were there, and the CIO of course was being formed. But a guy—I guess you call him an agitator—was fighting for something radical, something subservice called “Social Security.” I forget this guy’s name. He wanted to get attention, so like the kids of ’68, you know what he did? There was a big ballroom. He hopped onto a chandelier, and he swung on the chandelier, back and forth. It was a scandal. But he brought attention to what he was for, Social Security, not too different from the kids seeking attention about the war and civil rights and all else in ’68. So, Roosevelt was answering.

Remember also, when the Fair Employment Practices Act was passed, he wasn’t for it, because he was thinking about the South and the vote. But A. Philip Randolph had planned a march on Washington, and others, and so the—it was a tremendous—and how are you going to stop that march? So, finally, this bill—I forget the number—was passed. So that’s one of the bases, Amy and Salim, the basis of what happened during those ’30s. It was always a—the deep movement in the South.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking, of course—and I’m sure most of you are familiar with this mellifluous, elegant voice of Studs Terkel.

STUDS TERKEL: Oh, keep talking. Keep talking.

AMY GOODMAN: See, now you don’t have to go to physical therapy this morning. We’ll do the therapy for them.

STUDS TERKEL: That’s right.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: We’ll butter you up enough, man.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, I wanted to go to look at a comparison between President Clinton and Richard Nixon. Would you say it’s fair to say that on domestic policy, in fact, Richard Nixon was actually to the left of Bill Clinton?

STUDS TERKEL: Well, there again, it was Nixon—not Nixon the angel, but Nixon the practical politician—replying, or trying to reply, to meet the challenges that came about at that moment. There was a good number of bottom-up stuff. See, what happened, I suppose, is a challenge to people who may be listening, who are parts of various movements—peace or environmental or green movement, whatever it might be. There’s been a disparity. There’s been a breakdown on some—but these are going on. I think they’re individual enclaves, little ones, but there’s been no coalescence, and which leads us to the big question: since when are there only two parties as something testament or written in stone? And if ever there were a time for a new party—and perhaps the word “New Party” itself can be capitalized—ever there were a time for a third party, who decided that the two—we know the two contributors are the same, pretty much. Republicans get more dough from the big boys than the Democrats do, but they both get—it’s pretty much in the seven figures, around there.

AMY GOODMAN: No question about that. More than seven figures.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: More than seven.

STUDS TERKEL: Oh, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And if you look at this convention, I think, just the Democratic convention, they got about $40 million.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: About $12 million from the federal government; the rest, those corporations.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, I’m thinking about the contributions, of course. And so, when in the world are we going to have an alternative, a third party? Which is the big question.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: You know, we really asked that question in 1984 and ’88, when Jesse Jackson ran.

STUDS TERKEL: Mm-hmm.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: And he kind of stoked the embers of desire for such a third party. And Jesse made a statement similar to what you made, trying to justify support for Clinton, that Clinton is not the progressive politician that we want—

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: —but pressure from the bottom will make him that progressive politician.

STUDS TERKEL: Well, we do know he’s quite pliable, to put it mildly.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Indeed.

STUDS TERKEL: He’s putty.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: So, what do you think—what do you think about Jesse Jackson’s role in—

STUDS TERKEL: Well, it’s an interesting one. I don’t know. As you know, I’m fond of Jesse Jackson, though once upon a time I had a public conflict with him, way back, about—oh, I think—I thought—and I had realized that I shouldn’t—I shouldn’t have done it. I think he was wrong. It’s a long story, but I shouldn’t have done it, because I immediately got calls from every phony in the book, saying, “Studs, you’re great. You’re on our side.” And then I knew I did something wrong. But Jesse, I think, has grown. I think he has developed from the time when he reputedly had the bloody shirt when Dr. King died. I think he’s grown tremendously since. And Marshall Frady’s biography, I find a very good one on Jesse.

You think of a guy—he’s the only guy could ever get the hostages back home, the only one. And yet, what’s the first question they ask [inaudible]? “Where’d you get the money? Who backed you?” See? But in a way, he’s—I think he’s trying to play the political game. He thinks to survive or to have his thoughts survive. And so, he made the speech, not in prime time—nor, for that matter, Cuomo—because, remember, the announcers—here’s the—do you mind if I take on this, just for a minute? The perversion of the American language. Aside from the whorish times we live in, the language has been perverted. So they were kept off prime time, he and Cuomo, because they were liberals. The L-word. So the L-word has replaced the C-word of the ’50s. So, “liberal” has now become that. And so, the language itself has become very perverted.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Indeed.

STUDS TERKEL: What are liberal—and so, that’s part of the [inaudible].

AMY GOODMAN: You know, Studs, one of the things we talked about throughout the week, this whole issue of prime time, the networks saying we’re going to give one hour to the convention.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: I don’t care, you know, how much time they give to the convention each night. Maybe even that’s too much. But I think the outrage of it is they say to the Democrats, “We’re going to give you this time, 9:00 to 10:00,” and basically they have the Democrats producing their show, because instead of using that hour to say, “We’re going to take Jesse Jackson from two hours ago, and we’re going to take a bit of Cuomo,” they will run what is running then. And so the Democrats decide what message they want to put out and who they want to put it out. Also Ed Kennedy—Ted Kennedy wasn’t in prime time.

STUDS TERKEL: See, yeah, not unlike—by the way, this applies to the Republican convention, as well, both.

AMY GOODMAN: Absolutely.

STUDS TERKEL: Not unlike the Gulf War coverage. The generals said, “We’ll tell you.” And the reporters, with the exception, of course, of—we know who sued: The Nation and some of the other alternative, In These Times magazine.

AMY GOODMAN: Pacifica Radio.

STUDS TERKEL: But the established press went right along. Just the analogy is stunning. There was the war, and here’s the convention, and the same—and the reporters just were supine, or the publishers.

AMY GOODMAN: And, you know, not only did we sue for restrictions around the Persian Gulf War, us group of independent media outlets, but the major media wouldn’t cover the suit, because they weren’t involved in it.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, of course, I—just, I know, before I came on, you and Salim had as guests Dave Dellinger and some of the younger—of course they were blocked out, and with ridicule, naturally. The way to do it, much more effective this way than the way David the elder did it then, you see. Much more effective. This time was just blocking them out—easy, smiling, blocking them out.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Studs, you were talking about the perversion of the language.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Another aspect of that, I think, is how the radical right, the militia right, has appropriated much of the language of the left in a very unique and strange—

STUDS TERKEL: Well, think of the word “life.” Pro-life, as though people for choice are pro-death, you see? Pro-life, you see. They don’t ask of the life of someone—maybe the life of the fetus, but not of the life of that same fetus 18-year-old kid going to war. They don’t—not too worried about life then.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: That’s right.

STUDS TERKEL: You see. But coming back to this matter of the language taken.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Right, and Pat Buchanan seemed to have struck a chord among those people. What do you think about—

STUDS TERKEL: You bet Pat Buchanan struck a chord. He came out against NAFTA. Remember that? He spoke of the peasant rebellion. We know he was a demagogue. We know he’s a bigot. But the fact is, he was able—maybe populist through the years had become. George Wallace was a populist to a great extent, calling upon blue-collar people, working—and so, Buchanan touched real chords. Of course he did.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Well, it would seem like that would be a hint to the Democrats or some other party to strike similar chords to evoke the same kind of response.

STUDS TERKEL: Of course. But you have—what have we got? We have something called flaccidity.

AMY GOODMAN: Flaccidity, let me write that down, look it up.

STUDS TERKEL: Flaccidity, there’s nothing—no muscle, no nothing. It’s—oh, God—viscous, sort of like a—

AMY GOODMAN: Studs, I don’t know if this follows from flaccidity, but I wanted to ask you about American labor and about what is being described as a resurgence. You have Union Summer this summer, with thousands of kids around the country.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve got the unions, the AFL-CIO, pouring $35 million into campaigns to basically defeat the Republicans—

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —and bring the Democrats into control. What do you think of the alliance of the labor with the Democratic Party?

STUDS TERKEL: Well, it’s not fully. I mean, it’s not so much—I’m interested more in the resurgence of the labor movement. And remember, there are new constituents now, members. There are minority groups, women, Asian people to a great extent, as well as black people and Hispanic people, especially in the service employees unions. And once upon a time, the unions were run by hoods and thugs. What I’m really worried about is the Teamster election of this moment, which is a key one. Ron Carey, for the first, had a rank-and-file vote. And now the papers, the press—here again we come to the joke, the grotesque joke: liberal media. If ever there was a grotesque joke. And so, the press are playing up Jimmy Hoffa as a hero in Chicago. There’s a guy named—an old hack named Hogan, the ally of Hoffa, anti-the rank-and-file vote, who’s played up in the papers and the columns as a hero, even said the film guy in town. They pay tribute. See, it’s this aspect, again, of the press and its—well, what’s the word, whatever the word is.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: I think “whorish.”

STUDS TERKEL: “Whorish” is the word. Brass check. See, Upton Sinclair wrote a book about the press, the whorishness of the press, went back in 1950, called The Brass Check, because the brass check—when a guy went to visit a sporting house, house of ill fame, whorehouse, he’d pay $2, and the madam would give him a brass check, which he gave to the girl. At the end, she would cash in her brass checks and get a buck for each one, say. So, The Brass Check was his book about journalism.

AMY GOODMAN: Studs, we have to break for one minute, and then we’ll be back. Yes, we’ll be back with Studs Terkel. I’m Amy Goodman, with Salim Muwakkil, here in Chicago. You’re listening to Democracy Now!

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! But, Studs, in answer to your question, “How is this going?”

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s going well. And it’s going particularly well, because you’re here with us. Again, for our listeners, I’m Amy Goodman, with Salim Muwakkil. And, you know, Studs said he’s here because of Salim, and he knows Salim from this radio station, WFMT. And I should reveal a secret. We came to Chicago not for the Democratic National Convention, but just to spend some time with Salim, because we’re always doing it by phone. It’s nice to spend time.

STUDS TERKEL: Salim Muwakkil, by the way, I think is one of the most perceptive of all commentators, not simply on the subject of race, but connecting it with all other aspects. So, interesting that the Sun-Times wants him, but he wants—still wants to stick with In These Times.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Oh, whoo! Can’t ask for a better testimony there.

STUDS TERKEL: It’s true.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Studs, well, speaking of writing and whatnot, what books do you have planned coming out.

STUDS TERKEL: Well, the one, I suppose, that—I won’t say “last” one—but the one is a sort of compendium of—starting with Division Street to the last one, but not in that order, sort of a—my century. I call it My American Century, since I was born when the Titanic went down. That went down, I came up, you know. But that, as Jimmy Carter said, who said life is fair? You know. And that was 1912. And I want—I said to the surgeon, “I want four more years, up to” — he said, “I’ll give you 10.” I said, “I want four. Never mind the 21st century.” I [inaudible] any bridges to it, either, because just—I’m thinking about technology’s effect on us all. But they’re coming back. So this book is a compilation of all the introductions, plus five or six portraits from each of the ones, ending up with Age.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, speaking of age and you talking about talking to your surgeon that you want four more years, has the operation you’ve gone through changed your view of things?

STUDS TERKEL: No, except that maybe if you—I just more am—I shouldn’t say this—darkly amused by things. As you get older, there’s a sort of a Samuel Beckett approach gets in there, you know. And so, no, it hasn’t changed. It was very funny, because the two surgeons—there were two. One was the heart, and that was seven hours. And then, three days later, they find out my intestines are almost gangrenous, and so there was four hours more. So it’s my heart and the belly. And both those surgeons—you know, surgeons are the prima donnas of the hospital. I thought of one as Olivier, the other as Brando, you know. And so, but they were skilled. I shouldn’t be kidding them, because they saved my life. But in any event, no, it hasn’t changed my view any, other than a little more impatient, I suppose, with what I consider hypocrisy, you know, and the way—and, I guess, the perversion of the American language, to some extent.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I’m very glad you’re sitting here with us. You’re certainly a star, but it makes me think—and I hope you’re not horrified by this—of other stars, and that’s the stars that they brought out, a different kind of stars, at the Democratic convention. I mean, it was really shameless. This was completely produced for TV. It was produced by a Hollywood producer. And throughout the Democratic convention, they had video moments, well-produced pieces, you know, aimed for television. And they had stars throughout the week. You had Jennifer Holliday, the singer. Emmylou Harris sang. Edward James Olmos. You had the cast of Rent, the Broadway production, performing.

STUDS TERKEL: You’re naming the better ones. That’s the interesting thing, see. There was a slew of others, not nearly in the—but the—see, the point is, of course they own TV. And they went on for hours with this trivia and shameless sort of almost—well, quite vulgar stuff, as a matter of fact. But strangely enough, Nightline had Haskell Wexler on, the marvelous, very courageous cinema—who did Medium Cool. And that was on Nightline, was on about a quarter to 12:00. Now, only Haskell Wexler was on, talking demonstrating in the ’60s, and it was a marvelous program, I thought. And that was on a quarter to 12:00. Until then, it was an hour and a half of the stuff you described, which tells you what they think of [inaudible].

SALIM MUWAKKIL: It’s all scripted. And it appears that this may be the last of these kind of conventions, because I don’t think that the American people can actually tolerate this kind of hypocrisy much longer.

STUDS TERKEL: To think—you know, just to be autobiographical, I was 12 years old, 1924, and it was a summer resort. And I wouldn’t leave the Atwater Kent radio, because I was taken with the voices of the Democratic convention in New York, 102 ballots. It went for 10 days. And I was glued to it, because, you know—and I heard the same voice, the Alabama first voice: “24 votes for Underwood.” That was the favorite son. And it went on, and there was a deadlock between Al Smith and William Gibbs McAdoo, Wilson’s son-in-law. And they chose a Wall Street lawyer, Davis, who was clobbered by Calvin Coolidge. By this time, my brother got me onto—I became a third party groupie. And by that time, Bob La Follette ran for president here. So I thought of Bob La Follette. And so, there was a reunion of University of Chicago Law graduates about 25—1960 — ’50 — ’60 election, and votes for president. And so, my sleek fellow alumni, the vote was about 54 for Nixon, 52 for Kennedy, and one for Bob La Follette. And they all looked at me and said, “Oh, him.”

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Old habits die hard.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Studs, before you go, how did you end up doing what you’re doing?

STUDS TERKEL: Accidental. The creation of accidents. I went to law school, God forgive me. I did. It was not their fault, it’s mine.

AMY GOODMAN: When?

STUDS TERKEL: In Chicago, I went to University of Chicago Law School through '34. I dreamed of Clarence Darrow and woke up to Julius Hoffman. And so, then, I mean, that's it. No contract, it wasn’t for me. So, I became an actor in radio soap operas—I was a gangster, always getting killed—a disc jockey, even a sportscaster for a while. And finally, WFMT and a TV program, part of Chicago-style TV. So one thing led to another, and my publisher, André Schiffrin, once heard some of my interviews, and he liked them. And so, the rest, as we say, is history.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Pantheon used to—later Pantheon Press, right? But now—

STUDS TERKEL: Pantheon, now New Press.

SALIM MUWAKKIL: New Press, OK.

AMY GOODMAN: Compare radio to TV.

STUDS TERKEL: Well, I like radio much better, of course. Radio, you’re—as we’re talking now, you’re free. We have an engineer, Don, but that’s about it. And on TV, you’re subject to every aspect, as well as, of course, [inaudible] because your sponsors are not, as far as I understand, Amoco or General Electric, you know. And so, therefore—this is very free, of course. You couldn’t possibly do this is on—but not only the substance, the very nature of it makes you more of an automaton. You know, who are the commentators? They’re readers of notes. They know how to censor themselves. That’s the big thing. We have no heavy hand of government censoring us. There’s no—there’d be a samizdat if there were, you see? We don’t have that. We have something far deeper: self-censorship, knowing what to ask, what not to ask. And so, you will have no attack on General Electric on NBC, since they own it, right? So, of course, that’s it throughout. So radio—I love radio because imagination, the voice, you can sing, and you can bring in music. And, in fact, you at the microphone are in charge.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, speaking of being in charge, it makes me think of not being in charge, and that is—the Democratic and Republican convention, those that were in charge were the corporations. And interestingly enough, in San Diego, one of the many parties that were held celebrating one of the delegations was Time Warner’s party. And do you know that Time Warner would not allow the press in?

STUDS TERKEL: Shades of Gulf War all over again.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you very much for joining us, Studs.

STUDS TERKEL: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: I hate to kick you out of the studio, but I know you have to go to your therapy appointment, and that’s very important to me.

STUDS TERKEL: Yeah, yeah, yeah, and viva Pacifica!

SALIM MUWAKKIL: Viva! Viva Studs Terkel!

AMY GOODMAN: Studs Terkel on Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! We’ll be back with a discussion about what’s happened this week and what’s coming up, and then poetry from the protest pen here in Chicago.

Media Options