Topics

Guests

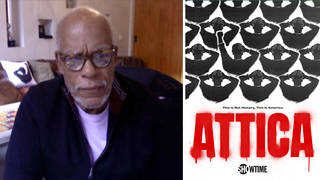

- Akil Al-Jundiformer Attica inmate.

- Frank Big Black Smithformer Attica inmate.

- David Rothenbergone of the 35 negotiators brought into Attica.

- Malcolm Bellspecial prosecutor assigned to prosecute the state police, and author of The Attica Turkey Shoot.

- Elizabeth Finkattorney for Attica prisoners in their ongoing suit against the government.

- Danny Meyersattorney for Attica prisoners in their ongoing suit against the government.

Twenty-five years ago today, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller waged war on the inmates of Attica State Prison in New York, ending a three-day prisoner uprising. The rebellion started on September 9, 1971, when inmates overpowered guards and took over much of Attica to protest conditions at the maximum-security prison. At the time, inmates spent most of their time in their cells and got one shower per week. Days of tense negotiations followed in the prison yard, and the rebellion was on its way to being resolved through diplomacy. On the morning of September 13, Governor Rockefeller ordered state police to storm the facility. Through a haze of tear gas, police opened fire, killing 29 inmates and 10 hostages.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Twenty-five years ago today, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller waged war on the prisoners of Attica State in New York, ending a four-day prisoner uprising. The rebellion started on September 9th, 1971, when inmates overpowered guards and took over much of Attica to protest conditions at the maximum-security prison. At the time, inmates spent most of their time in their cells and got one shower per week. Days of tense negotiations followed in the prison yard, and the rebellion was on its way to being resolved, until the morning of September 13th, when Governor Rockefeller ordered state police to storm the facility. Through a haze of tear gas, police opened fire, killing 29 inmates and 10 hostages.

EXUMA: This is a new song. It’s called “Attica.”

[singing] Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica

Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica

WILLIAM KUNSTLER: The commissioner told us last night that he was going through his own ordeal and that he had not made up his mind what to do. We implored him, as we implore him now, to have no force in there. The prisoners told us yesterday when we were inside, they would everyone if there was a show of force, all the hostages, and they would die themselves. And I am absolutely convinced they mean every word of it. And they also say that they will do nothing to any hostage or in any violent way if the status quo remains. They want to continue to talk. If they go in there, it’s going to be a massacre in this prison, and it’s on the heads of the authorities if it takes place.

EXUMA: [singing] They sent for the man up on Government Hill

He told his army to shoot to kill

They sent for the man up on Government Hill

And he told his army, oh, shoot to kill, yeah

WILLIAM KUNSTLER: And I have only but— nothing but the greatest of sympathy both for the guards and for the inmates inside. Time can produce something here, but a loss of time and a show of force will produce only death and misery, not only here, but I’m sure it will have a reaction in Black ghettos and other areas throughout the country.

PAUL FISCHER: For four days, some 1,000 inmates of Attica State Prison had been in control of the facility. They were holding 38 hostages as they negotiated with authorities through a citizens’ observer commission for compliance with 30 demands. As of Sunday night, September 12th, the inmates and the authorities were deadlocked in at least two of the demands: amnesty and the removal of Vincent Mancusi as the warden of Attica State Prison. The deadlock ended at 9:48 Monday morning, September 13th, when a force of more than 1,700 state troopers, National Guardsmen, sheriff’s deputies and corrections officers assaulted the prison from the air and from the ground. When it was over, 30 inmates and eight of the hostages were dead. And in the days that followed, more died of their wounds. As of today, the death toll from the Attica assault is 43.

Earlier this morning, in the predawn hours of this morning — it’s now about a quarter to 10:00, but in the predawn hours of this morning, about 50 state — 50 state troopers made their way inside, armed with clubs and rifles. Oh, there is a great deal of gas emanating from — emanating from the prison.

REPORTER: Well, is Governor Rockefeller going to come here? Will he consider doing that? Do you think he should come here?

WILLIAM KUNSTLER: He should come. His refusal to come here is a monstrosity, because what he is saying is “Kill these men. I have no concern. All I want to do is restore law and order.” And I think that’s a rotten exchange for lives.

REPORTER: There are no Black — I have not seen any Black guards or Black state troopers. Wouldn’t that help the situation, since most of the inmates are Black?

WILLIAM KUNSTLER: Don’t you know there are almost no Black troopers, and there are virtually no Black guards in the state prison system? I better go in.

PAUL FISCHER: Attorney William Kunstler is trying to get into the prison. He has been allowed in before, but now he is being stopped at the door. Those dull thuds have stopped now, so, apparently, the Army helicopter dropped its load back there. Now I hear more of them now. And apparently it is gas, because a force of sheriff’s deputies armed with rifles and wearing gas masks is going inside the prison as the Army helicopter goes back over the wall again. At this point, it is safe to say that authorities here are now using force to try and end this prison rebellion, though there is no idea of what is happening to the inmates inside exactly and no idea what has happened to the hostages, either.

EXUMA: [singing] Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica

Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica

How many times must we die

Before we are allowed to live

How many lives must we give

Before we are allowed to live

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: The injuries are very serious.

PAUL FISCHER: This is a medical assistant who declined to identify himself. Reporters spotted him as he was leaving the prison, his blue medical uniform covered with blood.

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: They range from compound fractures, severe lacerations, gunshot wounds, multiple gunshot wounds. It’s very [inaudible] —

REPORTER: We understand one of the guards was shot, one of the hostages was killed by gunshot wounds. Is that true?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: I can’t comment on that. I don’t know.

REPORTER: How bad was it?

REPORTER: How were most of the hostages killed?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: I can’t say. I really can’t say how they were killed.

REPORTER: We understand that eight of them had their throats slashed. Is that right?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: This is a rumor, but I can’t confirm that. I wasn’t in there when they treated those people.

REPORTER: Are there many still that you’re treating in there seriously injured?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: They’re treating quite a few right now.

REPORTER: How many [inaudible]? I mean, ballpark figure?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: I’d hate — I’d hate to estimate.

REPORTER: Just an estimate.

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: I’d say a hundred, anyway.

REPORTER: A hundred being treated?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: That’s right.

REPORTER: How would you describe the situation as it looks in there?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: It resembles a war.

PAUL FISCHER: Some 12 hours after the assault ended, 38 people were dead, eight of them hostages. Reporters were told that the hostages had had their throats cut by the inmates, that one of the hostages had been castrated, and a few of the hostages had been dead several days before the assault. All of this information, which had come from the authorities themselves, later turned out to be untrue. The hostages, in fact, died fom bullets fired by the state troopers that day. No one had been castrated. Embarrassed, authorities then imposed a blackout on news emanating from the prison.

EXUMA: [singing] Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica

Oh, why do you live the big white lie

Watching your brothers and your sisters die

While you are living the big white lie

Your brothers and your sisters die

Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica, Attica

Black, black, black

Going uphill on the railroad track

Black, black, black

Going uphill on the railroad track

Black, black, black

Going uphill on the railroad track

Black, black, black

Going uphill on the railroad track

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re listening to Democracy Now! on this 25th anniversary of what happened at Attica on September 13th, 1971. Included in that archival tape mix is the original reporting of Paul Fischer, who was the news director here at WBAI, the Pacifica station in New York. He now works for Dan Rather at CBS. Also, the voice of late attorney William Kunstler. He died on Labor Day a year ago.

Right now we’re going to be talking about Attica for this hour, and we’re joined in the studio by a full roster of people who were there or who have been dealing with Attica ever since. We’re going to begin with two people who were there. We’re joined by Frank “Big Black” Smith. He was a former prisoner at Attica, as was Akil Al-Jundi, who was there in 1971. Akil Al-Jundi is now with the Legal Aid Society in the criminal defense division. And Frank “Big Black” Smith is a mental health counselor and a paralegal.

Well, let’s begin with Akil Al-Jundi. It must be hard to go back to that 25 years with the sound, but I know, in talking to you over these years, it’s not something that’s far away from your mind. What caused the original Attica uprising?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: The cause for the original uprising was the deplorable conditions that existed at Attica State Prison in Attica, New York, as well as other prisons within the system. Plausibly, plausibly, it’s the incident that happened on September the 8th of 1971, which involved two prisoners — one Black and one white — where correction officers mishandled and abused them, and prisoners reacted to it.

AMY GOODMAN: That they were friends, and there was a division at Attica —

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — between Black and white?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Well, there wasn’t really a division by the prisoners, but a division by the prison administrators. They never wanted to see Black and white unity. And so, it was hard to see two prisoners — one Black and one white — having come from other prisons and having had — they both came from Auburn, which was at that time one of the most liberal prisons in the state of New York to be able to frolic and stuff like that. So they tried to put a stop to it, because they were perpetuators of institutionalized racism.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Akil, about a month ago, we did a special on Democracy Now! on the life and times of Johnny Spain about George Jackson, about the killing of George Jackson, a prison leader and a former Black Panther. How did his killing affect you at Attica?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Well, George’s killing affected me and a whole lot of other people tremendously. George was in California, which is the West Coast, and we were in New York, which is the East Coast. But many of us devoured almost everything written by George or written about George. George, as you know, was called the field marshal. And so, a lot of us, we identified strongly with him, whether people were members of the Black Panther Party or whatever respective organization they belonged to or just prisoners, because he represented, for us, what — just like Malcolm, what George represented or was doing was basically what we were all about.

And so, when George got killed on August the 21st of 1971, we had to make a big decision how to show our concern for it. And eventually what we did is we had a day of silence and no eating in the prison mess hall or cafeteria to show our sign of solidarity and concern for our comrade.

AMY GOODMAN: So you fasted. And how did this contribute to the uprising?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Well, I think what it did is it placed the state on notice that, one, there was a different trend in terms of how prisoners were looking at what was going on not only to them at a respective site, but looking at it on the international — on the national level.

AMY GOODMAN: Big Black, what were you doing on this week 25 years ago at Attica?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: That’s strange, Amy. I was just thinking about it this morning on my way here with Liz. It’s basically the same kind of day — rainy, wet, you know, and something was in the air. You know, I just couldn’t figure out exactly what that something was, but I knew something was going to take place that Monday morning.

And my feelings today is 25 years that we’ve been dealing with this and still dealing with it in the courts. And I won’t say that I don’t see an end to it — I don’t see an end to it, but there’s got to be an end, sooner or later, in the courts. So, my feelings is, it’s twofold now. I got a good feeling: I thank God that I’m still here and around today. And then I feel bad, because I think about all the brutalization and the assaults and all the murders and all the state atrocities that was put to us since September 1971.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, tell us exactly what happened on that day. Where were you in Attica? Were you in the courtyard?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Yeah, I was in the yard.

AMY GOODMAN: With how many other prisoners?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Twelve, thirteen hundred.

AMY GOODMAN: And when did you see the police moving in, the guards, the sheriff’s deputies?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Well, first, we heard — we’d seen a helicopter. And we heard an announcement: “Put your hands on your head and come to the nearest” assault person — that’s what we call it — “and you won’t be harmed.” And then they started shooting. And then gas started dropping.

AMY GOODMAN: And where were they shooting from?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Right in the yard, right out of the helicopter on the buildings and various places around surrounding the yard. I thought it was hail, you know? I thought it was rocks. I never could imagine that it was really live bullets. So, a lot of peoples went to the ground, and then we started seeing them coming over the walls from different yards, from A yard, C yard, and coming into D Block.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about the tear gas?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: The tear gas was there. We started pulling our clothes off, because it was sticking to us. We started rubbing milk on us, because that’s supposed to —

AMY GOODMAN: So, how did you escape the gunfire?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: I don’t know, to tell you the truth. I never could answer that question, because right around that time I started hearing my name. You know, “Where is Big Black? Where’s Black? Where’s Black?” And some of my friends, people who were around me, got me in the hallway in D Block corridor, and I laid on the floor. And eventually — everybody’s new there inside. And then we crawled into A Block yard.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, when we come back, we’re going to talk about what happened afterwards, the beatings afterward. We’re also joined by two of the attorneys for the Attica brothers, and we’re joined by one of the people who was called in as an observer. We’re also joined from New Hampshire by a man who was, many would have thought, on the other side, assistant special prosecutor called in to investigate what happened at Attica, and he’s written a book called The Turkey Shoot. You’re listening to Democracy Now! We’ll be back in 60 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! The Exception to the Rulers. I’m Amy Goodman.

REPORTER: Likely to die?

UNIDENTIFIED: Wait a minute.

UNIDENTIFIED: Let him answer the question!

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: Yes. Yes, they are. This is not a professional opinion, but I believe that they’re going to die.

REPORTER: About how many, would you say, out of the hundred or so?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: I couldn’t say how many.

REPORTER: But again, let me ask you the question. Just describe the scene as you saw it in there.

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: Well, where they were bringing the prisoners in, there was a room, about eight by 10, and it was completely covered with wounded people. It was very bloody. The wounds were very serious. I know there were a number of deaths in front of me. And it’s very depressing.

REPORTER: How does it look in there? What would you compare it to?

MEDICAL ASSISTANT: It looked very, very bad. I wouldn’t compare it to anything. It’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen.

AMY GOODMAN: And that was a medic on the scene, September 13th, 1971. Reporters caught him as he was walking out, covered in blood, a bit shell-shocked. And that’s what he had to say. We are joined by a number of people, but before we move on to talk about the legal ramifications of the story, I wanted to go back to Big Black, Frank “Big Black” Smith, who was one of the prisoners there, September 13th, 1971, 25 years ago today. After the shooting, Big Black, you crawled inside, you and the other prisoners, naked. You didn’t get shot. But what happened to you next?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: You mean during the shooting, Amy. It wasn’t after, because the shooting continued, you know, for a long, long while after they got into the yard. After I crawled into A Block yard, I heard someone calling my name. And eventually, the officer that was in charge of the laundry where I worked at, he said, “Here’s Big Black. There he is.”

And they got me, and they took me over to the side of the yard adjacent to A Block corridor, outside, and they laid me on the table, and they put a football under my head, under my chin. And I’m laying on my back, and the catwalk is up over me, and people are standing up over the catwalk. And they’re dropping the shells after they fired the gun down on me, and they’re dropping cigarettes on me, and they’re spitting on me. And they’re playing with my testicles and telling me, if I move and the football fall, that they were going to kill me. And they kept asking me questions, like “Why you castrate the officer? Why you bury the officer alive? Why you do it, Black? Why you” — you know, crazy questions. And I’m saying that “I didn’t do no such thing. I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

But meanwhile, in the back of my head, inside the hallway, they had set up a gauntlet. And in the gauntlet, they had broke glass in the middle, and they had like 30 to 20 — I don’t know exactly who it were, but assault people standing on each side with sticks, what they call “nigger sticks,” and had people running through the glass and beating them as they went. And I could hear this. People were hollering. And they were running down the hallway. And I laid on the table, I guess, three, four, five hours.

AMY GOODMAN: As they tortured you.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Yeah, as they tortured me and threatened me. And I just kept praying and kept saying — well, I knew it wasn’t right, and I just was saying, “Well, I wish — I wish this would end.”

AMY GOODMAN: When did they finally stop?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Well, into the afternoon, it didn’t stop. You know, into the afternoon, eventually they asked me to get up off the table. And my legs was dead because they was hanging over the side of the table, and I couldn’t hardly stand up, really. So then I went inside the hallway, and I had to go through the gauntlet. So I did the best. They broke my wrists in different places. They opened my head up.

And I finally got through to A Block, inside the block, went through the block and had to go outside again to go to HBZ entrance. That’s special housing unit. And when I got to that entrance, they had five or six more correction, because I knew a lot of them. And they started talking about the same thing: “Why did you do it?” And they started — you know, we — not “we,” really. All I was doing was blocking, trying to get away from it, because I was on the floor. And they beat me a lot with their sticks and stuff.

And then they took me to the hospital and dumped me in a room by myself. And I was really bleeding a lot. My arms was real slow. And in that room, I know it was some state troopers. They had me spread eagle on the floor and was [pounds table] in my testicles again and had a shotgun, and they put the shotgun down to my eyes, in each, double barrel. And I closed my eyes. “Open your eyes up, nigger! Look at this!”

And someone came in. I believe it was a National Guard person. He said, “Get on out of here! This is not your business.” And then he kept me in there for a while, and then they took me into the medical part of the hospital on the ground floor. And they bandaged my head up and put me on a stretcher and took me to the elevator and dumped me on the floor and took me up to the cell block and threw me in a cell, which nothing was in the cell but a mattress and a pillow. And I didn’t have any clothes on. And in September, it really gets cold, that part of the state. You know, I’m trying to get up under the pillow, get up under the mattress or something to keep myself warm. But I couldn’t go to sleep. I couldn’t relax, because I’m still traumatized behind what happened. And all through the night, they started playing Russian roulette with us.

AMY GOODMAN: David Rothenberg, you were connected to Attica because the prisoners asked for you, asked for the Fortune Society, which you had founded, an advocacy group for ex-convicts. There was a large group, actually, of observers, more than 30 observers, who had been called to Attica to negotiate. Can you talk about your trip there and whether you understood that this was happening to the prisoners after the attack?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Going up there, we got a call on — what was it? Thursday, the 9th? From Arthur Eve, who said that —

AMY GOODMAN: Who’s now a state assemblymember.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: He was a state assemblyman, too, saying that we were on the list of requested observers in the negotiation that was going on. And my background, growing up in a middle-class, all-white community in New Jersey, working in the theater, who had been involved in a prison play, and got involved with the Fortune Society in '68, so, by ’71, I had just had my big toe in the water and didn't really understand the ramifications of it. And probably because of that, I said yes.

And we went up to Attica and were met by a state vehicle, which drove us into the prison. And then we were brought into the yard about 8:00 or 9:00 at night, and we spent the night there. We knew there was death in the air. That was the feeling. Mel Rivers turned to me and said, “There’s death here.”

AMY GOODMAN: Mel Rivers also worked at Fortune?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Yeah, he was one of the brothers from Fortune Society that went up with me. And Kenny Jackson was the third guy. And in the morning, the observers realized that there were too many of us, and we narrowed our group down to five people: Tom Wicker, Bill Kunstler, Herman Badillo, I think, Clarence Jones —

AMY GOODMAN: Politician here in New York. Clarence Jones from —

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Clarence Jones, who was the publisher of the Amsterdam News. And I’m not sure who the fifth one was. Maybe it was John Dunne, who was a Republican state senator.

AMY GOODMAN: But you had gone into the prison on the Saturday.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Yeah, we were in the yard overnight, on the Thursday night to Friday morning.

AMY GOODMAN: What was it like there?

DAVID ROTHENBERG: Tense, very tense. I mean, you had 1,200 men who had been in captivity for a period of time who had finally risen up against the oppressive conditions. They were holding hostages. We knew that the state — we could see the state troopers with their weapons on the wall. It was an extreme — it was war. It was war between a Third World nation and a power structure. The thing that’s most memorable, I think, for me, of the whole incident is flying back to New York on a Monday morning listening to the helicopters, listening to that report that your listeners heard earlier, sitting there with a bunch of ex-cons all crying because they knew what the state of New York was doing, then hearing the report from the state that the inmates had killed, stabbed and castrated the hostages who they had held —

AMY GOODMAN: The guards that they had taken.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: The guards. And then, the following morning, a simple, decent medical examiner from Wyoming County said those reports that the media took and swallowed, the official statements that they swallowed, hook, line and sinker, were all untrue and that everybody — inmates and guards — had been killed by the state of New York. We had been led to believe that they waited, a calculated decision to go in on Monday morning, because they didn’t want to have trouble in the inner cities on a weekend, and that it was a political decision to go in on Monday, when people were back at work, and also that it was the time when Governor Nelson Rockefeller had aspirations still to be president and was trying to shed a mislabel of a liberal administrator, and he wanted to make a law-and-order stance and, like his grandfather in Ludlow, was willing to slaughter a group of fellow Americans to establish a new image in his political aspirations.

AMY GOODMAN: And for that, he was later chosen to be the vice-presidential running mate of Gerald Ford.

DAVID ROTHENBERG: And I think that Attica was the political feather in his cap that allowed that to happen.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, before we talk about the case today, because, yes, there is a lawsuit on behalf of the Attica brothers today, I wanted to bring in Malcolm Bell. Now, he comes at this from a very different place. He’s written a book called The Turkey Shoot and, in fact, was a longtime Republican, had voted for Nixon three times. Malcolm Bell, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you tell us how it is that you got involved with the case at Attica?

MALCOLM BELL: It was pure chance. I had been in civil litigation for a long time, and it didn’t seem to be going anywhere, and I wanted to get into criminal. And I answered a blind ad for prosecutors, and it turned out to be the special prosecutor for Attica.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did you do next?

MALCOLM BELL: I was assigned to prosecute some inmates. And that was very interesting. And then I turned out to be the one person who was really willing to prosecute the police who had done anything wrong. And since they had killed 10 times as many people as the inmates, there was a chance they had done something wrong. And I found that they basically rioted with their guns and committed murder. And the only question was whether there was enough evidence left, after they destroyed a good deal, to prosecute them. And there was.

AMY GOODMAN: What kind of evidence did you have?

MALCOLM BELL: The main evidence was their own written statements that they fired their weapon at inmates — shotguns, rifles. And the traditional statement went on to say, “He was running at me with a knife.” We had photos and eyewitnesses to prove that he wasn’t. And so, at least you had reckless endangerment, even after they had destroyed the ballistics evidence, you know, not kept track of who had what rifle. There was one rifle killed three inmates, and nobody kept track of who had it, which totally violates state police procedure.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what happened then, why you weren’t able to bring these prosecutions to fruition. I mean, you were working with a grand jury for what? Something like two years?

MALCOLM BELL: No. No, it wasn’t that long, actually. We had begun presenting evidence in May of '74, that late because the office had no wish to prosecute the police, I realized later. And by August, it looked as though there were several dozen of the state police that we could indict for — a few for murder and a great many for reckless endangerment. And I checked with the grand jury years afterwards, and it turned out, yes, they would have indicted these people. And then Rockefeller was nominated for vice president, and suddenly the lid came down. They just cut off the prosecutions. I mean, it's obvious what would have happened to his nomination, which was having tough going in the Senate, if, say, 60, 70 state police that he had ordered into the prison were indicted.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s get the timeline here. You have Nixon resigning. You have Gerald Ford becoming president, him choosing vice-presidential running mate, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller. Now, how did that squelch the investigation? I mean, what specifically happened?

MALCOLM BELL: What happened was, we were going forward with the evidence — we had been going forward with the evidence against the troopers who fired their weapons when they shouldn’t have and basically committed murder. And suddenly the investigation — I was told to examine a whole bunch of people. I hadn’t even heard their names or learned how to pronounce them, and — on the state police cover-up case. We were eventually going to prosecute the obstruction of justice case, what New York calls hindering prosecution. But suddenly, before the main case is finished — cases are finished, we switched over to this other thing. It was a clever ploy, and it happened right within days after Rockefeller was nominated for vice president. And after that, they even shut down that case. And they banned me from going to the grand jury, and I couldn’t question the witnesses I wanted. I was fascinated to hear Black just now, because I would have liked to hear that in the grand jury.

AMY GOODMAN: And what stopped you from hearing it?

MALCOLM BELL: Direct orders from my superior, who worked for Louis Lefkowitz, who was Rockefeller’s man who helped him win election and was his man all the way.

AMY GOODMAN: What were you saying, Big Black?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: I wish I could have told you, too, Malcolm. By the way, how are you feeling? It’s nice to hear your voice.

MALCOLM BELL: It’s good to talk to you, Black. I’m fine. How are you?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: I’m hanging in there.

MALCOLM BELL: Good.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Yeah.

MALCOLM BELL: I got to say, it’s very spooky to sit here today and listen to the reports of Clinton building up force to attack, and Dole wanting to do even more, because both of them want to be president. And here we’re talking about Rockefeller being so tough, because he wanted to be president, in his war against a Third World country.

AMY GOODMAN: In a little while, we’re going to hear from Tom Wicker, The New York Times former columnist, who was one of those five final observers. And he gave a speech recently here in New York about his experience and wrote a book called A Time to Die. In fact, he wrote the foreword to your book, Malcolm Bell, called The Turkey Shoot and talked about you as a hero, a hero that maybe a lot of people didn’t know about, certainly the Attica brothers may not. Did you realize what he was doing at the time, or was that very much squelched, the kind of work he was doing on the other side, trying to investigate the state police, Akil?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Yeah, we knew who Malcolm Bell was. You know, in all fairness to him and all fairness to us, he was the prosecutor. And so, definitely, we didn’t have good feelings about him at the time. But as we began to understand, because of the work that we had been doing, the defense committee, the brothers and our people pressing for indictments against state troopers and sheriffs, etc., and seeing him take on that task, we got a better understanding of what he was trying to do.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we have two other attorneys here. They’re Liz Fink and Danny Meyers. And they have been leading the battle on behalf of the Attica brothers for 25 years now. We just have a few minutes before we break, and then we’ll come back to the discussion, but, Liz Fink, can you lay out what the case is against the state?

ELIZABETH FINK: The case is against the state what you just heard, which is we are suing individuals of the state of New York, because we can’t sue the state in federal court, for the assault and for the torture and brutality which occurred against all of the brothers in 1971.

AMY GOODMAN: Why can’t you sue the state?

ELIZABETH FINK: Because there’s an amendment to the Constitution called the 11th Amendment, which does not allow you to sue the state in federal court. You have to sue individuals. So we sued Rockefeller, and he was protected by the courts and dismissed out of the case. And we sued Monahan, who was head of the assault force. And we sued Oswald, who was the head of the Department of Corrections. And we sued Mancusi, who was the warden. And we sued Deputy Karl Pfeil, who was the associate warden. And we got a verdict against Deputy Warden Pfeil for all the torture and brutality that occurred in the prison after the assault. And we got hung juries against the rest of the people.

And this case was filed five minutes before the statute of limitations ended on September 13th, 1974. And at that time, we were in Buffalo fighting the criminal prosecutions, which Malcolm is talking about the other side of. There were 42 indictments charging 62 inmates with 1,489 felony charges, the largest series of indictments in the history of the state of New York. The prosecution cost about $150 million, for the investigations and the prosecutions. And what resulted was one conviction and seven acquittals.

Meanwhile, what Malcolm did was that he started in front of what was called the second grand jury, and he’ll tell you that. And the reason why they needed a second grand jury was because the first grand jury, which was convened in November of 1971, was so weighted against the inmates that there was no way that they would ever consider any crimes against the state. And, you know, there’s a person now named Aldo Barbolini, who killed two people in cold blood, who’s the postmaster of Middletown, New York, right? And they knew that he killed two people in cold blood, one Kenny Malloy, and Malcolm will give you the name of the other one, I think James Robinson. And —

AMY GOODMAN: He was National Guard at the time?

ELIZABETH FINK: No. The National Guard were the heroes.

AMY GOODMAN: Or state police?

ELIZABETH FINK: The National Guard were not part of the assault force. The only thing they did was medical care, right? They were not allowed to be in the assault force. They were the people who should have been in the assault force, but Rockefeller wanted to scourge the prison. And he wanted to have the effect that he did.

AMY GOODMAN: And we’re going to talk about the politics of Rockefeller in just a minute. We’re talking to Liz Fink, the lead attorney in the Attica brothers case. Danny Meyers also joins us, an attorney in that case. Malcolm Bell is with us from New Hampshire, and he was the assistant special prosecutor looking into the case of the state police, although indictments were never brought. He’s written a book called The Turkey Shoot. And we’re joined by David Rothenberg, one of the observers invited by the Attica prisoners to come up to do the negotiations with the Attica authorities. And “Big Black” Frank Smith, who was one of those prisoners, and Akil Al-Jundi, who was another. You’re listening to Democracy Now! When we come back, we’ll also be joined by Tom Wicker, former New York Times columnist. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: You’re listening to Democracy Now!, Pacifica Radio’s daily grassroots election show, and this is a special on Attica. Twenty-five years ago today, on September 13th, 1971, acting on the orders from then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller here in New York, state police, surrounding D yard, where the hostages were being held, opened fire and, in six minutes, killed 29 inmates and 10 hostages, wounding 89 others. Former New York Times columnist Tom Wicker was one of the negotiators, one of the observers who was invited there. He wrote about the Attica massacre in his book, A Time to Die. And he was in town last week and spoke about his experiences.

TOM WICKER: After 22 years of reflection on the massacre at the Attica correctional institute on September the 13th, [ 1971 ], I believe even more strongly than I did at the time that it need never have happened. I’m still shocked at the callous procedures of the state of New York, which resulted on that day in the deaths of 29 inmates and 10 hostages, all killed in six minutes of indiscriminate gunfire by state policemen and corrections officers, as they call prison guards. I find it as hard as ever to believe that for the 83 inmates wounded in the same fusillade, no medical care had been planned, and, for hours after the shooting stopped, little was provided. It is no less sickening today that after the orgy of shooting was ended, another orgy was allowed to begin, the torturing and beating of inmates who had been recaptured by guards whose conduct had helped precipitate the same inmates’ revolt.

I am no more able than I was in 1971 to understand or explain why prison officials aftewards told a lie that the 10 dead hostages had had their throats cut by inmates, when in fact they were victims of wild police gunfire, or why my colleagues in the press accepted and spread that lie without vigorously questioning it, although I interpolate here to say that one thing people have to realize about prisons is that they’re built as much to keep us out as they are to keep them in. So, therefore, it was not easy — would not have been easy for any of my colleagues in the press to go in and find out how those hostages actually had died. Nonetheless, I find it shocking that no more serious effort was made to find out than was made, even by The New York Times.

But most of all, I am haunted by the belief — haunted by the belief, grown to near certainty, that none of this necessarily had to happen. A remark by Herman Badillo, one of the outside mediators who had tried and failed to stop the slaughter, gave this book its title: “There’s always time to die. I don’t know what the rush was.” The closing word of A Time to Die, written in the near aftermath of the events of September 13, 1971, describe my feelings as I was leaving Attica that terrible day. He knew there would have to be a time for anger. And that time came.

For years, for years, I seized every opportunity to speak and write about the need for changes in the squalid and inhumane U.S. prison system, for a measure of rationality in the treatment of offenders in America. How much good that did can best be told from the fact that in 1971, there were about 250,000 Americans in the prisons of that day, but on May 9th, 1993, the Justice Department announced that 883,593 persons were warehoused in these fortresses of degradation, which were much the same as in 1971. I believe the number is now over a million. The U.S. now has more prison inmates than any nation in the world per capita and absolutely — a shameful first place.

I long ago concluded, therefore, that my small personal crusade was in vain, that prison reform, in fact, was the most hopeless social cause this side of gun control. The fear of crime was and remains so great in this country that people are not only willing, but anxious, to lock ’em up and throw away the key. That the dollar cost of this policy is insanely high, while its social purpose of reducing the incidence of crime has abjectly failed, seems to a fearful citizenry to be irrelevant. A child of failure, written in pain and travail, A Time to Die was dedicated to the dead at Attica, in the hope that in its pages those unhonored dead might be seen at last as men and not numbers.

AMY GOODMAN: And we are talking about Attica today on the 25th anniversary of the state laying siege to Attica, killing more than two dozen prisoners and a number of guards who were hostage. That was Tom Wicker, former New York Times columnist and author of the book A Time to Die about his experiences at Attica and what happened there. We have a room full of guests. We’re joined by Akil Al-Jundi and Frank “Big Black” Smith, both prisoners at Attica in 1971. Big Black just described what happened to him after what Malcolm Bell calls the “turkey shoot,” when he was brought — not shot, but tortured. And we’re also joined by David Rothenberg, who was one of the observers brought in by the prisoners, and by the attorneys for the Attica brothers. We’re joined by Danny Meyers, as well as Liz Fink.

Danny Meyers, talking about the present, we’re talking about a million people who are in jail today in this country — pretty astounding figures Tom Wicker brought up, the highest number of prisoners in the world today. But you represent specific prisoners, and those are the Attica brothers. What’s happening with this lawsuit? It’s 25 years later.

DANNY MEYERS: Yes. The lawsuit has to be seen in the context of Attica and that the lawsuit continues the struggle that began 25 years ago. And that struggle is the struggle for human rights under all circumstances. And what happened at Attica is the example for the legal community, as well, that developed around support, that the commitment for human rights is an essential commitment, and we must see it through.

The lawsuit today is in a posture in which we have to go back to court, believe it or not, and continue to try the state. And the lawsuit is going to be reupped, if you will, on March 31st, 1997, back in the federal courts in Buffalo. What’s happened is that the state, and for many, many years Rockefeller and his lawyers and the state of New York, and the judge have attempted to thwart their being held accountable and responsible for the massacre 25 years ago, and that as we sit here today, neither Akil Al-Jundi, Frank “Big Black” Smith or the remaining 1,289 prisoners have received a dime from the state of New York for the brutalization that they received, for the deaths that occurred and for all the harm and the carnage and everything else that has been described. They haven’t been compensated for that loss.

AMY GOODMAN: Malcolm Bell, how do you feel when you hear that? You were the assistant special prosecutor, who was supposed to be prosecuting these state police. Why did you end up leaving, by the way?

MALCOLM BELL: I left because they had absolutely thwarted me in every effort I had made. They had forbidden me to call eyewitnesses to the shooting. They eventually banned me from the grand jury. They had forbidden me to walk down one avenue after another in pursuit of the most pertinent, most relevant evidence. And finally, I just felt I had done all I could from the inside, and I’d best resign in protest. And that’s what I did.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, the case, at your end, remains there.

MALCOLM BELL: I just — you know, it’s totally frustrating. And yet, the way things work, I mean, it’s so similar to the impunity you have in Latin American countries where the security forces commit wanton murder and torture and get away with it. They’re protected by the powers that be. And that’s just as true in New York state, unfortunately.

AMY GOODMAN: You had wanted to bring five murder indictments against state police?

MALCOLM BELL: I had hoped to bring that many. I hadn’t finished collecting the evidence. Liz mentioned one of the cases. The case of James Robinson was an egregious case. She mentioned his name. He was lying wounded on the catwalk, and a trooper walked up to him, fired a shotgun through his neck at the range of five feet. And the state police had destroyed some of the photographs of that, but we had others. And there were a number of cases. Most of them would have had to be reckless endangerment, due to the fact that the state police had taken care to minimize the existence of ballistics evidence.

AMY GOODMAN: There’s no statute of limitations on murder, is there?

MALCOLM BELL: That is correct.

ELIZABETH FINK: And although Barbolini came into court in Buffalo in 1991 and took the Fifth Amendment —

AMY GOODMAN: The state trooper.

ELIZABETH FINK: That’s right. Forty-seven times, he was brought up, and he had to take the Fifth Amendment 47 times.

AMY GOODMAN: Liz, David Rothenberg had mentioned earlier the medical examiner, the guy upstate who said, “No, the prisoners did not kill the hostages.” What happened to this guy?

ELIZABETH FINK: Well, what happened, Malcolm can talk about that, too, because he went to visit him later on. Malcolm became — we tried to get Malcolm to testify for us in the federal trial. The judge would not let him in as an expert.

AMY GOODMAN: Why?

ELIZABETH FINK: Because the whole [inaudible] of this lawsuit is that when the state does as bad as it did in Attica, then they have to continue to do bad to hide what they did. And what happened with Edland, Edland was a Nixonian Republican, and he was a medical examiner. And all he did was look at the bodies, and he determined that they were shot. As a result of that, they branded him a communist, right? They brought up Michael Baden to examine his findings, and — both Oswald and Mancusi. And Baden testified to this at trial.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Oswald, again, the head of —

ELIZABETH FINK: Yeah, the head of the prison system, and Mancusi, the head of the warden. They brought Baden in, and they said, “Edland’s a communist. We know he lied. You have to go and see it.”

AMY GOODMAN: Now, it has to be very clear here — and Tom Wicker also referred to it — that right after the shooting, right after, if you will, the “turkey shoot,” the PR people came out, and the authorities came out —

ELIZABETH FINK: Oswald.

AMY GOODMAN: — and said —

ELIZABETH FINK: Oswald.

AMY GOODMAN: — said that the hostages had been — that their necks had been sliced open.

ELIZABETH FINK: But it was even more than that. Oswald and Houlihan, who was the publicity person for the Department of Correctional Services, came out and told a fantasy story. They talked about hand-to-hand combat. They talked about fighting going on for four-and-a-half hours. And this was reported verbatim by The New York Times. Fred Ferretti testified for us in 1991 and referred to his article. It went on. It was fantasy. It was fiction. On the front page of the paper, it had list of hostages killed by the prisoners. And when they were talking about the people being castrated, they were referring to a particular guard by the name of Michael Smith, who was shot in the groin by a .270 rifle four times. He was operated on at 10:30 in the morning, and they knew full well that he was shot.

What happened to Edland was that he was terrorized by the state of New York. He could not drive his car. Every time he went out in his car, he was stopped and given a ticket. And he was tortured. He was ostracized. And his life was ruined. He died of a heart attack. Malcolm, remind me. What? He was about 55 years old.

MALCOLM BELL: He was much too young, much too young. And I got to believe the harassment and the abuse he took over his simple telling of the truth is really the reason that he’s dead today. He’s another — add him to the list of casualties of Attica.

ELIZABETH FINK: And there are many, many lists of casualties of Attica, because the fact of the matter that people were so terrorized and so brutalized, and they were so tortured that, in 1992, we sent out a questionnaire, and over 400 people responded, and 250 of them have permanent injuries. We’ve sent people to psychiatrists. They all have serious psychological damage. And the state of New York, Governor Cuomo, Governor Pataki, Attorney General Vacco continue to commit the massacre at Attica 25 years later.

AMY GOODMAN: As we wrap up, I want to go back to who we started with and who this all began with, and that is the Attica brothers. And today we have two of the people who were imprisoned in Attica in 1971, Frank “Big Black” Smith and Akil Al-Jundi. And I want to ask what you feel, 25 years later, would be fair recompense for what happened to you on September 13th, 1971. Akil?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Fair recompense would be the state admitting that they did kill all these brothers, and, I guess, from a monetary point of view, if we could get some moneys. But, for me, it’s more a political situation as opposed to a monetary concern.

AMY GOODMAN: Were you beaten?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Was I beaten? I was beaten. I was one of the persons that was beaten severely. Not only was I beaten, I was beaten after having been shot.

AMY GOODMAN: You were shot in the courtyard.

AKIL AL-JUNDI: I was shot. I was one of the first persons to be shot. All right? And I was beaten severely. And I was tortured on the 13th, and I was tortured after the 13th.

AMY GOODMAN: Are the scars on your hand —

AKIL AL-JUNDI: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — from September 13th?

AKIL AL-JUNDI: They definitely are, and this scar over here. And also, the torture that I took at Attica prison that caused my doctor, Dr. George Reading, to have to take me out of Attica prison to Buffalo Memorial Hospital, and then was tortured there, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Big Black, as we wrap up the show, your thoughts on this 25th anniversary of your torture and the killing of many of the people you knew at Attica?

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: Mine would be directed to the governor. I wish that today that the governor would really, really take a stronger interest in what is happening with the Attica struggle, and don’t do like Rockefeller did. I wish he would sit down and talk with some of our people so he can get the real deal of what happened, because he wasn’t governor at that time, and Attica remains in 1996. Don’t do like the Cuomos and the Rockefeller and the Wilsons, and everybody just passed right over it. You know, stop reading papers that the lawyers that’s representing the state is giving you. Take time out. Listen to people like Arthur Liman and our legal team as the real deal of Attica, because Attica is all of us.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about New York state’s Republican Governor George Pataki —

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: That’s who I’m talking to.

AMY GOODMAN: — who is calling for hundreds of millions of dollars to be poured into more building of more prisons.

FRANK ”BIG BLACK” SMITH: That’s right. That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you all very much for joining us, Frank “Big Black” Smith and Akil Al-Jundi, both at Attica in 1971; Danny Meyers and Liz Fink, attorneys on the Attica case, that continues today; David Rothenberg, one of the observers who was there in 1971; and Malcolm Bell, who was a special prosecutor investigating the state police and their activities at Attica. His book is called The Turkey Shoot, and it’s out from Grove Press.

You’re listening to Democracy Now! Democracy Now! is produced by Julie Drizin. We had help today from Bernard White. Errol Maitland has been our engineer; our director, Brother Shine. Thanks also to David Sears, Sally O’Brien, Rosemari Mealy, as well as Sam Anderson. Our music on today’s show has been by Exuma. It’s called Snake, and the song is “Attica.” The album is Snake. You’re listening to “Jailhouse Rock” by Israel Vibration. Thanks also to Dred Scott Keyes. If you’d like a copy of today’s show, you can call 1-800-735-0230. That’s 1-800-735-0230. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for listening to another edition of Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now!

Media Options