Topics

Guests

- Noam Chomskyprofessor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and author of dozens of books, including Manufacturing Consent, Necessary Illusions, On Language, and his latest book, Profit over People.

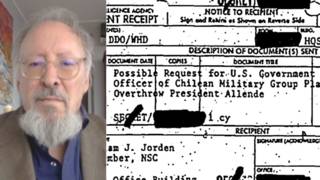

This week the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Also, the British government gives final word on the extradition of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet to Spain, and it is the 23rd anniversary of Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor. We speak with one of the country’s leading dissidents, Noam Chomsky. In his many books and lectures, Chomsky has provided irrefutable analysis on the U.S. continuous violation of human rights, both within and outside its own borders. From domestic policies such as welfare reform to U.S. support for repressive regimes and its international war crimes, Chomsky has taken the U.S. government to task for its disregard of international human rights principles, as well as for its double standards, as it preaches about human rights to the rest of the world. [includes rush transcript]

Related links:

- Noam Chomsky’s Birthday site

- Democracy Now! 5/7/98–Noam Chomsky on market democracy

- This Friday December 11th, British Home Secretary Jack Straw will announce the British government’s final decision on Spain’s request to have former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet extradited to face charges of genocide and torture. Call British Home Secretary Jack Straw: 011-44-171-273 4000, fax 011-44-171-273 2190. E-mail: gen.ho@gtnet.gov.uk

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This Friday, British Home Secretary Jack Straw will announce the British government’s final decision on Spain’s extradition request of former Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet. Human rights groups, as well as Chilean exile groups, are asking people to contact the Home Secretary, urging him to grant Spain’s request for the extradition of Pinochet so that he can face charges of genocide and torture in Spanish courts. However you feel about what the British government should do, you should let them know. You can call the British Home Secretary at 011-44-171-273-4000. That’s 011-44-171-273-4000. You can also email Jack Straw. The email address is gen.ho@gtnet.gov.uk. That’s gen.ho@gtnet.gov.uk. You can make a difference. You can also call the U.S. government, which has enormous influence over the British government, to pressure them to let the British government know how you feel.

Well, on this week in which the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of the U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a week when the British government will decide whether or not to extradite the former Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet, a day, today, which is the 23rd anniversary of the Indonesian invasion of East Timor, we speak with one of this country’s leading dissidents, Noam Chomsky. Noam Chomsky, professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, author of many, many books. His latest book is Profit over People. And he goes around the country and the world sharing his views, because it’s so difficult to get them out the easy way, which is through the corporate media, so he does it the long way: gets on a bus or a train or a plane and reaches people directly.

We welcome you to Democracy Now!, Professor Chomsky.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Hi, Amy. How are you?

AMY GOODMAN: It’s good—

NOAM CHOMSKY: And since when is it “Professor Chomsky”?

AMY GOODMAN: We welcome you, Noam.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, now that we’re being so informal, I do have to say happy birthday. But I promise to leave it at that.

NOAM CHOMSKY: OK.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, why don’t we start with the Pinochet story? And that leads to a bigger issue that you deal with a lot. In the last few weeks, we have seen a couple of op-ed pieces, in the Washington Post as well as the New York Times, by people from Human Rights Watch, and their main point, it seems, is to reassure the U.S. government, to say, you should support the extradition of Pinochet to Spain, but don’t worry, the United States would not be held—U.S. officials would not be held to the same standards. No, President Clinton would not be held to the same standards in the bombing of Iraq, for example, and other issues like that—a separation of what happens to foreign dictators and what happens to people here at home. You have always talked about the connections. Could you respond to the line that Human Rights Watch is putting out now?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, I’ve, frankly, been rather surprised to see those statements from Human Rights Watch, and I think they ought to seriously reconsider what they’re saying, to put it a bit mildly. I mean, actually, what their—their statement is, in fact, correct: the powerful will never allow themselves to be subjected to any form of discipline. So, for example, when the United States was condemned for — I’m quoting — “the unlawful use of force,” that is, war crimes, in the case of Nicaragua by the World Court, it was just dismissed. And in fact, Congress, controlled by Democrats, responded by increasing the immediately—increasing the unlawful use of force. And in fact, the words—I don’t think the words or wording was ever even reported in the United States. So, in a way, it’s correct, I mean, that Human Rights Watch is correct, factually, in stating that the powerful will not be held to account. But that’s hardly a contribution to human rights. Quite the contrary, that’s a demonstration, another—yet another demonstration that the law is a weapon against the weak, which is hardly something that you’d expect a human rights group to be applauding.

On the other hand, on the narrow question of the extradition of Pinochet, well, that’s a different question. I mean, recognizing that his defenders in Chile and in Latin America, who incidentally include the left as well as the right, not that they defend him, but that they oppose extradition, those defenders have a point. The point is that it’s Spain doing it to Chile, Spain and England doing it to Chile, not the other way around. And, in fact, it never would be done the other way around, simply because of power relations.

And that, today, is—well, the anniversary today is a perfectly good example. So, for example, England, which is—by now, has replaced the United States for some years as the major arms supplier to Indonesia, and hence has plenty of Timorese blood on its hand, and not only Timorese, well, you know, they’re not being—the Thatcher and subsequent governments are not being brought to account, although they’re doubtless involved in crimes that make those of Pinochet, horrible as they are, look mild by comparison. And the same would be true of—and people have talked about the absurdity of bringing Kissinger to an international tribunal because of his participation in the Chilean coup. And there’s something to that; it would be absurd. If Kissinger was brought to trial, it wouldn’t for Chile, but for far worse crimes than that, including the direct authorization of the invasion of East Timor and the direct support for it by instantly sending arms, by ensuring that the United States would undermine U.N. efforts to block the aggression, and so on.

And that’s only one. I mean, even that pales compared with his direct involvement in atrocities in Indochina, which is not just the bombing of Cambodia, bad as that was. Just in South Vietnam, the—what are called the post-Tet accelerated pacification campaigns—nice name for mass slaughter—instituted at once by the Nixon administration, were the worst atrocities in South Vietnam by a long shot. There are still thousands of people dying every year in Laos, mostly children and farmers, from unexploded anti-personnel ordnance that the U.S. simply saturated much of the land with, especially in the Plain of Jars. There actually is a British engineering team trying to remove some of these things, which are much worse than land mines. They’re designed to murder, not to maim or destroy. But they’re hampered by the fact that the Pentagon won’t even give them technical advice, information, let alone participate. Well, are those crimes? Is it a crime that thousands of Laotians are still dying? Yeah, I’d say so. But Human Rights Watch is correct in saying that nobody’s going to be brought to account for these.

And in fact you’d have to look hard even to find—actually, you can find a report about this in the Western press, in the Wall Street Journal even, but it happens to be the Asia edition of the Wall Street Journal, where their lead Asia correspondent, Barry Wain, had a pretty good story on it. He reported the estimate of 10,000 dying a year in Laos. And remember, what that means is farmers working in the fields, children picking up these tiny little objects and being blown up, and so on.

Well, I would say that’s something to think about on Human Rights Day. And in fact, the only point at which I would take issue with what you said, what I heard, is that I don’t think we should be celebrating Human Rights Day. I think we should be maybe commemorating it, or maybe mourning it, because the human rights—though it was a very important step to have the principles of the Declaration of Human Rights formulated 50 years ago, it is even more important to point out that the great powers, primarily the United States, don’t even give them the back of their hand.

AMY GOODMAN: Noam Chomsky, what do you say to those who say, no, they don’t support, for example, someone like Pinochet, but that this is very serious to start talking about violating national sovereignty and start having these powers, like the U.S. and Britain, determine what human rights are about?

NOAM CHOMSKY: I mean, as long as—it’s like having slave owners decide what’s a crime. I mean, maybe they would—I mean, no doubt, in slave societies, slaves committed crimes, for which they probably should have been punished, but to have slave owners decide that would not smell very good. And that’s essentially the point. The argument against unequal justice—I mean, look, we could say the same about the—what’s called the justice—the criminal justice system right here. A couple of years ago, two big major pharmaceutical companies, just to give you one case, conceded that they had misled the—lied, in other words—to the Federal Drug Administration and had claimed the drugs were safe when they knew that they were not—two of the major drug companies, huge conglomerates. There were about, if I recall correctly, about 90 known people, 90 known cases of people who had died from this. And they were indeed fined, because they conceded. I think they were fined something like $80,000. Well, suppose some kid in the ghetto kills 90 people. Is he going to be fined $80,000? No, but the—and that’s just an illustration. The justice system is radically unequal, but the argument is not, “OK, let’s not have any justice at all.” It’s, “Let’s make it equal.” And the same holds for on the international arena. Yes, Pinochet is a murderer, but very unfortunately, he’s not ranked very high, and you can find much closer cases where you don’t need to worry about extradition.

AMY GOODMAN: How difficult do you think it would be to have someone like Henry Kissinger be arrested? And do you think it’s possible at all and worth a movement to push for that?

NOAM CHOMSKY: It’s worth a movement to push for it, in the same sense in which it’s worthwhile to challenge the legitimacy of corporations, because they are illegitimate institutions, or, for that matter, to challenge the legitimacy of the Bolshevik state in 1960, when there wasn’t much chance of overthrowing it, or to challenge the legitimacy of any other authoritarian institution or illegitimate structure. It’s always made sense to challenge it, to raise—to instigate thought and action of the sort that would be appropriate.

Well, what’s appropriate depends on circumstances. Right now there isn’t a level of understanding or of organization or activism, which could lead to the imaginable prosecution of war crimes or crimes against humanity. It’s just not in the cards, just as it’s not in the cards right now to dismantle General Electric and put it in the hands of the workforce and communities. That doesn’t mean it’s not a goal that we should be aiming for.

You could say the same about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was worthwhile enunciating the principles, though a realistic person would recognize that those principles are going to be implemented, at best, very partially by the choice of the powerful. But it’s nevertheless worthwhile to enunciate them, to have them in mind, to act to try to change things, so they can be realized.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Chomsky—eh, Noam—

NOAM CHOMSKY: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Your book on—

NOAM CHOMSKY: That’s illegitimate authority again.

AMY GOODMAN: Your book, On Language, has been reissued, and I was wondering—you know, most people who hear about you outside of the world of linguistics don’t know much about the tremendous impact you’ve had on the world of linguistics. And if you could tell a lay audience about what your theory about language is, and does it connect to your political analysis?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, there’s some pretty elementary points about language. For one thing, it’s pretty clear that it’s a specific human system. It’s kind of like a—it’s like an organ of the body, basically, which other organisms don’t have. It’s a very recent evolutionary development. From an evolutionary point of view, it’s kind of the flick of an eye. In its fundamental properties, it’s quite isolated biologically. A language grows in a child pretty much the way the visual system grows, and to get closer to your point, probably the way the moral system grows, though we know much less about that. There are systems of the higher—what we call higher mental faculties appear to have, to the extent that we understand them, the properties of other biological systems, like, you know, the circulatory system or the immune system or the visual system. That is, they essentially grow along a more or less—a largely predetermined course, under the impact of experience, so there is variation, as there is individual in circulatory system. Language is one of those things, and it’s one of the very few higher mental faculties that we can in fact study for various reasons. So, we can find out what kind of properties these systems have in the various languages of the world. We can find out quite a lot about that, and a lot has been discovered. And more crucially, we can try to find out what is the uniform set of principles, sort of expression of the genes, from which they develop and arise. Well, that ought to be—here, there’s been really exciting progress, particularly in the last 15, 20 years.

And it’s—the broader scope is that it gives—this is a highly specific human capacity and undoubtedly at the root of a lot of the other things we do. It’s why humans have a history, for example. No other organism does. And humans study chimps, but not conversely. And humans are maybe destroying the world, possibly. You know, it’s not necessarily a beneficial mutation, from an evolutionary point of view. That’s for us to decide. But it also offers a kind of picture of how other things can be studied. For example, like the sense of justice or the moral faculty or our sense of our intuitive sense, which we have to come to learn about, because you do have to learn about your own nature. It’s there, but doesn’t mean it’s going to show—exhibit itself under existing circumstances. It has to do with any form of—any attitude that one takes towards human affairs, whether it’s to do nothing, to be a revolutionary, anything in between. It’s always based on some conception, intuitive or tacit conception, of, in simple words, what’s good for people, which has to do with the human nature and its characteristics. Again, we don’t know much about that, and it’s really hard to study. From a scientific point of view, it’s way beyond the bounds of really, very serious study at the moment. But there are—which is not to say it can’t be studied at all. In fact it is being studied, but—and it’s not to say that we don’t know—we don’t have a lot of ideas about it from history, experience, introspection and so on. But yes, there’s some—in that sense, you might argue there’s a weak connection.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Professor Chomsky, Noam, I want to thank you very much for being with us. We do have to go. I can’t believe I asked you that question with only three minutes to go, but we’ll continue the discussion, because it is a very important one. Thank you so much for being with us, and once again, happy, happy birthday.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Thanks a lot. Bye.

AMY GOODMAN: Bye, bye. Professor Chomsky, professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. And if you’d like to wish him a happy birthday, you can go to www.zmag.org, a big birthday page for Noam Chomsky. Thousands of people have been wishing him that happy birthday.

Media Options