Topics

Guests

- Johnnie CochranGeronimo Ji-Jaga Pratt’s lawyer.

- Stuart HanlonGeronimo Ji-Jaga Pratt’s lawyer.

In 1997 a judge reversed the 1972 murder conviction Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, who always maintained he was targeted and framed by the FBI and the Los Angeles Police Department because of his activity in the Black Panther Party. Three years later, we are joined in studio by Geronimo and his lawyers, Johnnie Cochran and Stuart Hanlon.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Juan, today we’re also going to go back in history to a case that could also affect our future and informs the way we look at this country today. We’re going to go back to the Democracy Now! archives three years ago, to June 11th, 1997.

AMY GOODMAN: From Pacifica Radio, this is Democracy Now!

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: And you can rest assured that I will adhere to every order and every instruction that this court indicates for me to follow. And that’s my word as a Vietnam vet and as a man.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Black Panther Geronimo Pratt is free after 27 years in prison, this after evidence surfaced that his accuser was a police and FBI informant.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Democracy Now! three years ago, and we’re going to continue with the report on that day, the day after Geronimo Pratt was freed.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: A song about Geronimo Pratt outside his courtroom yesterday. After 27 years in prison, former Black Panther Party leader Geronimo Pratt is free. To loud cheers from his family and supporters, Geronimo walked out of a Santa Monica, California, courtroom yesterday after a judge released him on $25,000 bail, just 12 days after reversing his 1972 murder conviction. Judge Everett Dickey ruled after hearing new evidence that the chief witness against Geronimo Pratt was a police and FBI informant who lied under oath.

Chris Richard was at the courtroom yesterday. He filed this report for Pacifica Radio station KPFK in Los Angeles.

JUDGE EVERETT DICKEY: Bail will be set at $25,000.

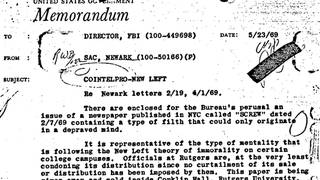

CHRIS RICHARD: It was a joyful scene at a Santa Ana courtroom as Superior Court Judge Everett Dickey granted a request by Pratt’s defense team and set bail at a figure matching the quarter century Pratt spent in prison. Ever since his conviction for a murder during an $18 street robbery in Santa Monica, Pratt has claimed that he was a victim of a law enforcement frame-up. And evidence has steadily mounted that he might be correct. First, his defense team uncovered evidence that the former Black Panther leader had been targeted in the infamous FBI program dubbed COINTELPRO, a program of dirty tricks launched in the late 1960s and aimed at destabilizing antiwar and Black Power groups. They uncovered evidence that FBI agents may have know that Pratt was attending Panther meetings in Oakland on the day of the killing, but concealed that knowledge. Then, last year, district attorneys’ investigators acknowledged that the star prosecution witness against Pratt, former Panther Julio Butler, was a paid informant for their office. During the original trial, Butler had claimed that he had never been a law enforcement informant. A state panel asked Judge Dickey to investigate the new revelations, and Dickey set an evidentiary hearing to determine whether Pratt should get a new trial. During the hearing, Pratt’s attorneys established that Butler was an informant not only for the DA, but for the Los Angeles Police Department, the Sheriff’s Department and the FBI. Two weeks ago, Judge Dickey said the jury needed to know that to render a fair verdict. He ordered a new trial. Today, Pratt stood in court to offer thanks.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Good morning, Judge Dickey. I just wanted to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your fair and courageous ruling and assure you that any further proceedings in this case, I will be the first one here, because I’ve been trying to resolve the merits of this case for all of these years, to find out who killed Mrs. Olsen, not any technicalities to try to put it off. And I am so happy that you’ve given me the chance to finally expose the truth about who killed Mrs. Olsen. And you can rest assured that I will adhere to every order and every instruction that this court indicates for me to follow. And that’s my word as a Vietnam vet and as a man.

CHRIS RICHARD: After bail was set, an exuberant Johnnie Cochran, Pratt’s attorney at the original trial, called his client a model of courage.

JOHNNIE COCHRAN: I think you can see we’re so very heartfelt that the picture of Geronimo Pratt that’s been put out is not an accurate picture. What he is really is an American hero. He is a decorated veteran. He is a person who has character and integrity. And in the face of this wrongful conviction, where the state used its mighty resources to convict him unfairly, he never wavered his innocence. And you saw at the end, when he spoke, the strength that emanates from this man. And I think that he can be a real positive force in this country as we move forward. When you’re falsely accused, to have the strength and the endurance to spend your first eight years in solitary confinement, he did what some of us only talk about. And so, we’re real proud to have had the opportunity to represent him.

CHRIS RICHARD: But Stuart Hanlon, who also has represented Pratt for the last quarter century, called today’s ruling a mixed victory.

STUART HANLON: It’s a great day for justice and for Geronimo. But it’s not a great day for our legal system. People have said that this justified the legal system. And the answer is no. The legal system that kept him in jail for 27 years for something he didn’t do cannot be justified by one judge having the guts to do the right thing. So we are exuberant today. It’s been a very long struggle. But it’s a great ending. We’re writing the final chapter. The district attorney is not writing the last chapter. The police department is not writing the last chapter. We are. Geronimo Pratt is writing the last chapter of his story, and it starts today in Orange County, when he leaves. And we say to everybody, “Right on! Let’s go get him out.”

CHRIS RICHARD: In 1972, COINTELPRO apparently was succeeding in destabilizing the Panthers. The organization was riven by factionalism, and the internal tension was rendered even worse by Panther founder Huey Newton’s drug abuse. Kathleen Cleaver was one of very few Panthers to defy Newton’s orders and testify in Pratt’s defense. She swore then that he was in Oakland attending Panther meetings around the time of the killing. But she couldn’t remember exactly whether Pratt was at the meeting on the day of the killing. Only two years ago did other Panthers step forward to solidify Pratt’s alibi. Cleaver says that over the years she has grown weary of the legal system treating Pratt’s case as different from all others.

KATHLEEN CLEAVER: What I said is that the time that I’ve observed the way the courts have handled this case, it has never been treated as a matter of law. It’s been treated as an aberration and as if the law doesn’t apply because this a Black Panther, threat to society, and we can just ignore the law. Finally, I’ve seen a judge who was willing to treat this case as a legal matter and apply the law as it existed before he was tried.

CHRIS RICHARD: Why couldn’t it happen in L.A.?

KATHLEEN CLEAVER: Because it’s a political cesspool driven by hatred and paranoia of blacks in general and Panthers in particular.

CHRIS RICHARD: But today, Pratt’s family focused on their immediate joy. His wife, Asahki, already is making plans.

ASAHKI JI-JAGA: I feel wonderful, wonderful. It’s been a long time coming. I was thinking about how long it’s going to take us to get him out of there, so we can get to my daughter’s graduation.

CHRIS RICHARD: As for Pratt, he too says he wants to move forward. Moments after walking out of the Orange County jail, he urged the public to remember the plight of other prisoners, notably Native American activist Leonard Peltier, who has been incarcerated for nearly as long as Pratt. And Pratt says he bears no hard feelings against his old adversary Julio Butler, the former Panther who played a pivotal role in winning a conviction against him a quarter century ago.

REPORTER: Geronimo, what do you have to say to Mr. Butler?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Huh?

REPORTER: What do you have to say to Mr. Butler?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Oh, just I wish him well, and I hope that he can wake up out of that stupor, or whatever he’s in, and begin telling the truth about his puppet role, his house Negro status, and so forth and so on, and come and tell the truth. And even if he doesn’t, the truth is going to come out. It took me 27 years.

CHRIS RICHARD: Right now, Pratt says he only wants to catch up on his family life. His 14-year-old son Hiroji graduates from middle school next Friday, and his daughter, 18-year-old Shona, graduates from high school in Marin County today. At the jailhouse gate, Pratt jumped into a waiting car for a dash to the airport. He says he wants to be present at that graduation.

This is Chris Richard reporting for KPFK.

AMY GOODMAN: And we thank Chris Richard for that report three years ago, the day after June 10th, 1997, when Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt was freed after 26 years, seven months in prison, eight of those years in solitary confinement. Since that time, over these last three years, Geronimo ji-Jaga has won a $4.5 million settlement against the City of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Police Department and the FBI.

You are listening to Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now!, as we are joined in the studio now by Geronimo ji-Jaga, as well as his attorneys Johnnie Cochran and Stuart Hanlon.

Geronimo, three years later, how does it feel today?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: It feels good to be able to come to WBAI and thank everyone and to see that you’re still struggling for the freedom of others, you know, to see old comrades such as yourself.

AMY GOODMAN: And what are you doing today?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Continuing to try to contribute to whatever I can contribute to. The main thing is freeing the rest of the comrades who are left in prison. That’s the main thing. You know, down there with mother in Louisiana, so I have to operate from that field of struggle.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’re going to break for stations to identify themselves. When we come back, we’re going to talk about all sorts of issues, including why COINTELPRO, the FBI’s counterintelligence program, is relevant today. Our guests again, Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, attorneys Johnnie Cochran and Stuart Hanlon. You are listening to Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As we talk with our guests for today, Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt, free now, three years ago, after almost 27 years in prison, eight of those years in solitary confinement, also joining us from the Bay Area is Stuart Hanlon, his longtime attorney, and his first attorney, attorney Johnnie Cochran.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, Geronimo, I’d like to welcome you and tell you I was mesmerized by the book as I was going through it last night, and especially what I loved was the history, your early history, in Louisiana, because of course I was in the Young Lords back in the '60s, and we had a lot of relationships with the Panthers, and you were out in California and always this sort of legendary figure that people on the East Coast heard about. But the story of how you shaped your consciousness and the history of your growing up, and especially about the deacons, was something that I had no idea of until I read the book. And I'm wondering if you could tell us a little bit about growing up in Louisiana and what shaped your political consciousness, how you ended up in Vietnam.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I grew up in segregation, and we had to deal with the terror from the Klan violence and, you know, other forms of ignorance from those peoples. But growing up in that kind of environment instilled in me a pride of — or a sense of nationalism, that we can govern ourselves, and we can protect ourselves, and we didn’t need to be with anyone who didn’t want to be with us. So, out of that, I was part of a group that was selected by the elders to get military training, to come back to the community, you know, and help protect it, relieve the old soldiers. It just so happened that when I was selected, Vietnam was happening, and I ended up in Vietnam and survived that, two tours, or two and a half. And when I came back, it was shortly after Martin Luther King was assassinated, so the black nation was more or less at one now with the — just being fed up. And everyone was saying, “Look, we have to do something.” So us young militant types were employed quite extensively throughout the nation. And so, this is how I ended up in these cities contributing what little I could contribute.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And when you say you were sent by the elders, as the book explains, they were people that, to the rest of the folks in the white society in Louisiana, would look at the local barber, these old guys that would sit around during the day and talk. But you had a whole different perspective on who they were and what they represented in the struggle for freedom.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Yes. Well, if you would meet them today, you would see — maybe in some, like in the case of Jimmy Harris or Alowishus, you would think you were talking to what you would call an Indian. Those traditions are still intact down throughout the South, where you respect your elders, you listen to your elders, and you heed their wisdom. And this is how I grew up.

AMY GOODMAN: And after you grew up and went to California, you got involved with politics of a different sort.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I came here first. I came here, then I went to Chicago. Then I went back to Louisiana. Then I was sent to Los Angeles to meet with this brother, this great brother named Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, whose elder was kin to my elder. And we’re all from Louisiana, like Johnnie Cochran’s father, and, you know, who were communicating among ourselves, just like they needed someone to come teach how to run a mimeograph machine. Remember those back in the day? And you needed someone to come and teach education culture. They also needed someone to come and teach how to defend oneself. And this was my calling.

AMY GOODMAN: And you got involved then with the Black Panther Party?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, with various organizations, including the Black Panther Party.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how did you end up in a courtroom being tried for the murder of Caroline Olsen? She was killed playing on a Santa Monica tennis court with her husband in 1968. You were caught and charged when?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I was arrested two years after that, in 1970, in Dallas, Texas, where I was instrumental in helping to organize the first Black Panther chapter there in Dallas, Texas, and other parts of the South. I was charged because of a conspiracy by the government that was led by the Hoover — what we call the Hoover-Nixon regime, which was an illegal conspiracy directed against the entire left, entire movement.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnnie Cochran, how did you get involved with Geronimo’s case?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: I was appointed by the court, by Judge Kathleen Parker, to represent Mr. Pratt in the murder case. I had met him and had sat alongside him in another case, the so-called Panther shootout case that took place in 1970, ’71, in L.A., was then the longest trial ever. And all the Panthers were pretty much acquitted of all the charges in that, and it was a bogus case. The court then appointed me to represent him in the tennis court murder case.

AMY GOODMAN: And what happened in that first trial?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Well, it was an amazing trial. I mean, we came in there knowing and believing strongly that Geronimo Pratt was innocent. We sought to set out to prove that innocence, to establish an alibi. We ran into some problems in getting other Panther members to come and establish the alibi. Mr. Pratt was in Oakland at the time of these killings in December of 1968. None of the other —- none of the Panthers who were affiliated with or aligned with Huey Newton would come. So, Kathleen Cleaver was in exile -—

JUAN GONZALEZ: And that was because he had already been expelled from the Panther party.

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Mr. Pratt had been expelled, and further, that the FBI had infiltrated so much that they had inculcated this kind fear and distress and whatever. They wouldn’t let him come testify. So we got Kathleen Cleaver to come back, and she was a great witness. She couldn’t pin it down as much as we wanted to, but we still thought we won the case. Jury stays out like 12 days or more, and they’re hopelessly deadlocked. But they end up convicting an innocent man. And it was all of the things we didn’t see that took place which caused that, that defeat.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Geronimo, what did you tell your young attorney, Johnnie Cochran, at the beginning? What did you think was going on? Why were you targeted?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, there was so much going on at the time. I was charged with so many murders. As I had indicated earlier, I was charged with the Tate-LaBianca murders. Well, I was picked up for it before Charles Manson. I was also picked up for another murder on the West Side, in which this youngster went and took part and killed someone. And they would hold us without bail. So I was thinking, at this time, that this was another murder or another tactic they were using to keep me from making bail.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did you think about that, Johnnie Cochran?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Well, I thought that basically, you know, throughout our trial, especially, and Mr. Pratt would always say, “They are out to get me there.” And I would always say, “Well, who do you mean by 'they'? What do you mean by 'they'? Who is this 'they'?” And of course, he was right. As I said, I learned a lot from representing Mr. Pratt, you know, that a little paranoia is healthy, that even paranoid people have real enemies. And of course, he was right, that it was “they.” It was the FBI. It was the counterintelligence program.

And Amy, how we found out this out was through the good offices, really, of Stuart Hanlon. In the intervening years after the conviction, through the Freedom of Information Act, we were able to find out a number of things, that this man, Julius Butler, who was the star witness for the prosecution, who got on the stand and said that Mr. Pratt confessed to him, and was asked by me, “Are you now, have you ever been, an informant for the FBI or any other agency?” And he said, “No.” He said, “No,” unequivocally “no.” He lied. At that point, he said that he informed 33 times. And, in fact, he was an informant for the LAPD and the L.A. County DA’s office. He was their confidential informant. They had done that. They had wiretapped our phones. They had informants in the defense environs, meaning that somewhere in our offices they knew everything we were going to do. They had failed to give us Brady material, that is, exculpatory material, where the husband of this lady who was shot had positively identified two other people. They kept that from us. They did all these things in an effort to neutralize — which meant kill, destroy, lock up forever — Geronimo Pratt, at the behest of J. Edgar Hoover.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Of course, at that time, you were already developing a reputation in L.A. I think in the book it says that you told Geronimo, “I’ve already won like 10 murder cases. I’m going to win this one, as well.”

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Yeah.

JUAN GONZALEZ: But you had no idea, even then, the depth of what the law enforcement officials, what extremes they’d resort to be able to get a person they wanted to get.

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Juan, it was just — it was incomprehensible to me to believe they would go that far. I thought, in a fair fight, we would win. And we would win in a fair fight. But it wasn’t a fair fight. And I didn’t realize the depth to which your own government could turn on a citizen — a decorated authentic American hero, two tours in Vietnam. But yet, because of the fact that he was a leader, charismatic in his own right, bright, a tactician, they saw him as a threat, and they were willing to do whatever. And not only did they do this to convict him, but then they held him basically incommunicado for the first eight years in solitary confinement.

And then they still — even at the very end, when Stuart Hanlon and I argued this case to that judge in 1997, we had convinced everybody in the courtroom, we thought, that Pratt had gotten no trial. I turned to the DA, whom I had known when I was a DA, and said, “Join us in asking to let this man out.” They still wouldn’t. In fact, even after they lost, they appealed it to the appellate court, and the court ruled unanimously against them. So, the cover-up, the attempt to keep this man locked up, continued to the very end. They didn’t give us anything. And then we sued them after that.

AMY GOODMAN: Stuart Hanlon, you joined the case after Geronimo ji-Jaga was convicted. He was sentenced to life in prison. In fact, the death penalty wasn’t in place in that time. If it was?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Yes, he would have gotten the death penalty — another reason we’re opposed to it. He would have at least received it.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you get involved with the case?

STUART HANLON: Well, I had just — I was in law school. I had come out from here, from New York. I had been at Columbia, where a lot of my political views had been developed. And I went into law to represent people who were attacked by our government, primarily non-white political people or poor people, poor white people. And Geronimo’s case, I became aware of it and met him. And not, you know, personally, he was a man who I immediately respected and grew to love, but politically — I mean, I think we couldn’t call it COINTELPRO then, but we knew that one of the greatest threats to what was happening in our country was the government targeting people because of what they said or what they believed and giving the police carte blanche to what they want to those people. And it still is a great threat to everybody, to democracy. You know, if the police get to do that, there would be no democracy now, you know, if they get to run this country. So that’s what was going on then, and it was really something that drew me to him.

And I think people should understand, I mean, now Geronimo — Johnnie’s here, he’s always been here, we’ve got a lot of publicity. Back in 1975, there was nothing. It was law students, and Geronimo was just languishing in the hole, and there was — nobody knew of him. And just a group of young people, with Johnnie’s help, just kept on going. And we used the Freedom of Information Act to get the government’s own records.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, one of the things that amazed me again in the book is that, of course, many people on the outside, in general American society, once someone is sentenced to prison, it’s like they’ve died. You know, they’re forgotten. But, of course, prison has enormous life, vitality, battles and struggles that go on inside them. And as I looked through the book, the story of Geronimo’s sort of development from — the book, of course, is called Last Man Standing: The Tragedy and Triumph of Geronimo Pratt. But what amazed me was your development from this targeted inmate, who spent all this time in solitary, to, in essence, you became a leader of the prison, where even the prison authorities began to rely on you to be able to help resolve conflicts that developed within the jail. And of course, as often happens with political prisoners, they are respected and admired by the other prisoners in the jail. Could you talk a little bit about that?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, yes, that was quite an experience, especially after coming from Vietnam and the struggle on the streets, going into prisons with all of the problems, with the divide-and-conquer techniques. And, of course, with the institutionalized racism, right in the wake of George Jackson, you know, the uprising. And San Quentin —

AMY GOODMAN: George Jackson, killed in prison.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Right, who was murdered. And Ruchell Magee and Jonathan, Christmas and McClain at the Marin County courthouse. And as Stuart had mentioned earlier, the SLA and all of these things, then the advent of the BGF, and so forth and so on. Then the problem with the Mexican Mafia, the Nuestra Familia, the Aryan Brotherhood. This madness every day was abounding in those prisons. Me being, say, arisen, descending to the top — or the bottom of that pack was an unenviable — enviable position again. Things just happened to develop that way. And I began to try to organize as best I could. I worked with the Vietnam vets. We were all serving 187s. And we organized pretty good.

AMY GOODMAN: One-eighty-sevens?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: That’s the penal code for murder, first-degree murder. And through that, we were able to get to a lot of the younger prisoners, to get them organized in a way they could change things also.

STUART HANLON: Geronimo really is minimalizing his own role there. I mean, you — to know what he was like, the visiting room was where all the races got together, all the different people in prison, and that’s where I would see him. And he’d come in, even in the early '70s, and no matter what the race, no matter what the people — the whites, the Chicanos, the Latinos, the Asians — their families would come up and say hi to him. It was unheard of. You'd come — Geronimo would come in the visiting room, and everybody would say hello to him, which meant a huge amount. It wasn’t just “hi.” It didn’t happen with anybody else. And it just — even the guards, even in the beginning, the baseline guards, even though they would really mess with him, had a real respect for him. It was really quite amazing to see.

AMY GOODMAN: Geronimo, before you were set free, 26 years and seven months after you went to prison, you were in solitary for eight years.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: We can say that, but what does that mean? What is life like in solitary? Where were you kept?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I was kept in the hole in San Quentin and Folsom. I started in the hole in Dallas, Texas, where I was busted, and then on to the holes in the Los Angeles County jail, which is like nightmares, when you’re talking about the holes in Texas and L.A. County, the old county jail, and then on to the holes in state prisons. But what it means is that this country tortures people. And right now, Hugo Pinell is going into his 27th year in the hole. Woodfox and Wallace and King, who are in Angola State Prison in Louisiana, are going into their 23rd year — year — in the hole. So, when you’re talking about eight years in the hole, and you look at this ongoing today, it’s hard for me to even talk about those eight years because it’s happening right now.

AMY GOODMAN: What is the hole? What does it look like?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: They vary in different states. They’re all punitive. They’re torturous. They are everything bad that you can think of. They put the worst mindless idiots over those sections in prison, where they can really, you know, mess over you.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you have a bed?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: No. Some now, they have beds, because of litigation. But even that is a slab of concrete, like resembling a gravestone. So, they vary in different areas.

AMY GOODMAN: The toilet, a hole in the floor?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Yes. The holes I was in, a toilet hole in the floor initially. And until Stu and Johnnie, we had a suit. Johnnie and Stu may want to talk about that. It was based on a law that derived out of the Reconstruction era in this history. After slavery was, quote-unquote, “officially abolished,” the Congress of 1871 enacted this jurisdiction called the U.S.C. — United States Code 42-1983 lawsuit, that was hidden from us for years and years and years. But the civil rights movement brought it out. And then the prison movement, through George Jackson, Ruchell, and lawyers like Brian Glick and Dennis Cunningham and others, we all got together, and we revived this. And through that vehicle, we were able to finally get straight to the federal court, in which we were — our conditions in the hole were improved.

AMY GOODMAN: How many hours a day are you kept in this single cell?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Twenty-four hours a day. And then, after the second year, it became 23 and a half. They would let you out for half an hour.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, when we come back from our break, we’ll find out how you kept your sanity. You’re listening to Geronimo ji-Jaga. He was found guilty of murdering a woman, Caroline Olsen, who was a peace activist. Then he was exonerated. There is a book about him now, just been published, by Jack Olsen, called Last Man Standing: The Tragedy and Triumph of Geronimo Pratt. Also in the studio with us, Stuart Hanlon and Johnnie Cochran, Geronimo ji-Jaga’s attorneys.

You are listening to Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! By the way, if you’d like to order a cassette copy of today’s program, you can call 1-800-735-0230. That’s 1-800-735-0230. We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We go to the sounds of that day, on June 10th, 1997, when Geronimo Pratt was released from prison.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: … proved that I’m innocent of any crimes of murder, and brother exposed the truth of COINTELPRO and illegal practices of the Hoover-Nixon regime. So I want to thank you again.

REPORTER: I want you to have this. What are you going to be doing next?

REPORTER: How does it feel to breathe free air?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: It’s — it’s hard to describe. You know, for 27 years —- and they give you the worst they could ever conceive. I mean, I still have brothers, like Ruchell Magee, Hugo Pinell, that’s still in the hole. And they have no reason in the hole. Beautiful brothers. Romaine Fitzgerald, the only Panther who’s also death row for a murder he didn’t commit, and everybody in the community knows it. And that’s one thing I wanted to say. One someone like Johnnie Cochran comes and tells you that “I’m representing this man from the community,” that means the community has empowered him. Johnnie knows what’s going on. Johnnie is deeply rooted in the community. So all of this stuff [inaudible] -—

REPORTER: [inaudible]

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: I contribute to the power of the people, that — the continuing struggle, that we will never relent when we’re faced with injustice. I can contribute the question to Stu Hanlon.

AMY GOODMAN: Geronimo ji-Jaga on the steps of the Orange County courthouse June 10th, 1997, after he had served almost 27 years in prison, eight of them in the hole. Our guests also, attorneys Stuart Hanlon and Johnnie Cochran — Stuart Hanlon, who has come to be involved with the Sara Jane Olson case, a Bay Area attorney; Johnnie Cochran, of course, known for representing O.J. Simpson, also now Puffy Combs. During the O.J. Simpson case, Johnnie Cochran, you said that the real story, the real case that people have to know about, because he was still in prison at the time, was Geronimo Pratt. Why?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Because I never — it obsessed me, because no matter what happened in my career, no matter what we did, he was still locked up, being held by his government wrongfully. And so, it was something that we lived with every day. And I took every opportunity to speak about it. And I remember being interviewed — I mean, because we were really focused on the Simpson defense, but I remember being interviewed over the lunch hour by a lady from GQ, and she asked me about what was really important. I said, well, you know, it’s important, what you’re doing in your job, but that case was what I was thinking was important to all of us.

And at that time, I said that the prosecutor, who was then now a judge, a Superior Court judge for L.A. County, wasn’t fit to be on the bench, because he had allowed — we had known — Stuart had uncovered in 1977 that this man, Julius Butler, was an informant, but the courts chose to turn a blind eye to that. They became part of the conspiracy, too, and the cover-up. So, I took it upon myself to say he wasn’t fit to be on the bench.

Turned out that was kind of prophetic, because later on, when we got a hearing finally in 1996, they used that, among other things, to transfer us out of Los Angeles County. And that’s how we got Judge Dickey. The plan, however, was to send us to this conservative kind of Orange County area, but we got a judge who understood what it meant to be a judge, an honorable man, Everett Dickey, who had the courage to listen to the evidence and give us a hearing. And he was the one who was instrumental in getting Geronimo released.

There were a couple other things we got. As you know, we —- a DA’s investigator, after 25 years, went right down, and in less than a minute, went into a safe, a locked safe, and found under B for Butler a card which said he was a confidential informant, their informant. Now, you can’t tell us they couldn’t have done that 25 years before. But that happened, and we got that. And then -—

JUAN GONZALEZ: And, of course, also you got the testimony of a former FBI agent, Michael Swearingen, you know, because one of the things that amazes me about —- that the society doesn’t understand, every organization of repression depends on human beings. And in every institution of repression, there are honest human beings who, at one point or another, feel something was wrong about what they did. Swearingen was involved in COINTELPRO, right? And he -—

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: He was, in fact, and I’ll let Stuart talk about this. But it is — you’re right about that. Swearingen retired, and at some point he came forward. And Stu will tell you about what he had to say.

STUART HANLON: He had been involved in many, what he called, black bag tricks of the FBI, dirty tricks — not murders, but illegal robberies and setups. And at the end, I think what turned him, what he said, he was called to go to the SLA shootout in L.A. in 1974, where the six members were killed.

AMY GOODMAN: Symbionese Liberation Army.

STUART HANLON: Yes, Symbionese Liberation Army. And he saw the joy with which the other FBI agents and LAPD went to go there, knowing they were going to kill these people, and he just walked away and I don’t think really ever came back. And one thing he showed us is the proof that Geronimo — the FBI knew he was in Oakland at the time of the murder, because it was the first time he ever found logs and records of wiretops that were missing. And the fact that they were missing the wiretaps of the Oakland office and L.A. office during this two-week period at the time of the murder, I think the offices were proof that they knew he was there.

AMY GOODMAN: So, really, it was the FBI wiretaps that helped to save you, Geronimo ji-Jaga, because you were a leader —

STUART HANLON: Or the lack of them.

AMY GOODMAN: — working in the Black Panther, right? And they were tracking everywhere you went. And if you were up in Oakland, they were tracking your phone calls, and Swearingen seeing that they were gone.

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Right.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: And also, later —

JUAN GONZALEZ: But see, I think that has to sink into the listeners. The FBI’s own wiretaps and surveillance knew that you couldn’t possibly have committed that crime, and yet they went along with and participated actively in the frame-up.

STUART HANLON: I think people have to understand, the greatest threat to our society is letting law enforcement run wild, with the approval of their higher-ups, whether it’s J. Edgar Hoover or Bill Clinton or Janet Reno, whoever it is. When we give law enforcement unlimited power, unbridled power, democracy falls apart. And that’s one of the major lessons of Geronimo’s case, because people have to understand what law enforcement does when they have unlimited power. They will always do the same thing. They will do — the ends will always justify the means, because their ends are to get their view to take over. And it’s just incredibly destructive. And, you know, it’s just — and two other policemen came forward, who were wonderful. They were old men at this point, two LAPD officers. Two African-American officers came forward and finally, with a lot of encouragement from Johnnie, who knew them, finally told the truth that Butler had been an informant for them. And I just think they didn’t want to end their careers with this lie on their records. So they were amazing.

AMY GOODMAN: But why, even with knowing that Butler was an informant, did that mean that what he said was a lie, Johnnie Cochran?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Well, I think that what happened was it meant the whole thing was a lie. What the judge had said, that if — and it was interesting, because by this time one of the jurors, Jeanne Hamilton, who had reluctantly changed her vote and voted for guilty, had said, if they had known — imagine if, at the trial, when you can cross-examine a witness and bring out the fact that you are an informant, you’re working the FBI, they put this case together, and have him say, “No, I’m not that. No, I’m just being a good citizen. I’m just doing my civic duty.” So it cut at the very heart of everything. That’s what made [inaudible]. It affected his credibility. He lied about everything. And we could then demonstrate that.

Furthermore, we found out that his big testimony was he had this letter he had supposedly written, protecting himself. Well, the letter was written by the FBI. The FBI had the letter all the time. They set it up. They got it after he wrote. So it was all part and parcel. And what we found out, as Stuart has mentioned, is we found out that he had been caught with a machine gun. He was working — he was worried about himself, and he was working off this case. The LAPD phonied up a report to cover for him, to get him out of that. And so, he was working it off. And Pratt was the victim of that. And that’s what happens in these courts.

And, you know, you’ve got to — as Stuart says, the big thing, and one of the messages we want to get out, is that in all of our society, there’s this issue of who polices the police. And the police are basically — the police officer on the beat and the others are the single most powerful figures in the justice system, more powerful than the Supreme Court. Look at the New York Times today, where you see this racial profiling, while they stop and they search, and they can shoot, and very little is done about it. So Geronimo Pratt is another result of that. So if we don’t wake up and pay attention to this and learn a lesson, what’s happening now in Los Angeles in this Rampart scandal, which is of epic proportions — and people just kind of like are going along with it, you know, kind of sitting there and, like, “Well, you know, those guys were gang members.” Well, gang members, they were framed, shot, maimed, and now they’ve got to pay all this money. And people are kind of sitting down and saying, “Well, you know, this is what happens.” It’s preposterous.

JUAN GONZALEZ: One of the — one of the, I think, most emotional parts of the book, Geronimo, was when you end up in the same prison with Huey Newton years later. Huey, who of course was an icon to many, many of us in the 1960s, but who then clearly fell apart in the later years of his life. And he’s the guy who expelled you from the party, who called you every name in the book. And suddenly now, you’re in prison, and he is brought back — I think it was on a parole violation.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Yeah, it was a sad day to see him come in.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And, of course, everyone expected now — you were a leader of the prison — that you would, in one way or other, try to get retribution on Huey. And could you tell us a little bit about what happened?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Right. It was sad to see Huey after all those years come in, after going through crack. He was a sad reflection of the man I had known. Huey was, I think, along with Eldridge, right at the middle of the essence of the center of the bull’s eye from COINTELPRO. Huey was always a great man, as were so many others who we are so quick to criticize without understanding the objective analysis. When you are targeted by COINTELPRO in such a way where they’re — someone is spending, say, $50,000 a week, you know, just to employ people to victimize you and to target you, even the strongest, it’s hard to stand up under that, not — though Huey, Eldridge and so many others stood up pretty good under that. But it was sad.

And Huey, when he’d come in, we didn’t harm him. We talked to him, gave him vitamins, and exercised him, and he began to rejuvenate himself. And he became very remorseful. So he contacted Stu, and they had a press conference, and he refused to leave prison, he said because he felt personally responsible for telling the Panthers not to testify for me when they knew that I was up there. And so, for his expulsion — at that time, there was no more Black Panther Party, so everybody was expelling everybody. So he was expelled by someone at this point. And so, we don’t look at it like that. We don’t look at it as a Huey Newton-Eldridge Cleaver faction, in our view. Maybe if we had more time, we could talk about that.

But yeah, it was sad to see Huey. And he, of course, was assassinated a year after he left. And strangely enough, he was trying to redeem himself in the community. And, well, it’s not strange to us that they would, you know, get him out of the way now, because he’s getting healthy again, and he’s — here, Stu might want to talk about how he had talked to Stu about doing more to clear up all of the wrongs that he had done, you know.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Stu?

STUART HANLON: Yeah, I mean, that — he came out from being in prison with Geronimo and really wanted to get reinvolved in the political system — not the Democratic Party, no — and try to organize the community again and get away from drugs. And he was, as Geronimo said — the government destroyed Huey Newton, you know, that he was targeted, and they got to him, and it was really sad. And at the end, he was just trying to help, and it just — the government continued to go after him.

AMY GOODMAN: Geronimo, we asked about you being in the hole, but didn’t get to find out, for eight years, how you kept up your strength.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, you are forced, when you are deprived of food — usually people go on a fast themselves, but if no one gives you food, then you’re on a fast. When your body is deprived of this junk that we call food, it goes through a cleansing process, through a cleansing process. It’s very — it’s like a catharsis. And if you’re not aware of this, and you’re holding on and you’re maintaining, what you’re doing is you’re practicing Ta’an, you’re practicing astral projection, all of those things that I later came to learn about after the fact. But it happens — it happened to me naturally, that I was on bread and water for a long time, so I would just throw the bread back out. And, you know, there was a lot of violence back then. So my body was deteriorating, and I would find myself in this long state of revelry, like meditation. And through that, I came at peace with myself from within, where I detached. I couldn’t get nothing, so I wouldn’t want for anything. So when you detach from everything, you find a freedom that you didn’t know existed, so…

AMY GOODMAN: And to those who say that the system has proved that it works by, ultimately, you being exonerated, what do you say?

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: I say that that’s not a — that’s the evidence to the contrary, that it doesn’t work too well. All of my — seven years of my twenties, every minute of my thirties, every second of my forties were taken away from me. If that’s a system working, then I think something’s wrong with your thinking.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And, of course, Johnnie Cochran, white America knows you as the O.J. Simpson lawyer, but African Americans and Latinos knew you for years before that as someone who stood up to the system in cases of injustice and knew about your reputation and your battle before then. What lesson did you get out of Geronimo’s case?

JOHNNIE COCHRAN, JR.: Well, I think that I learned a lot myself during this whole process, of always questioning the official version. The fact the government says it doesn’t make it so. In fact, you should question, you should scrutinize it. You should hold everybody up to scrutiny, because things are not as they appear, that the government has an agenda very often, and you have to be very much aware of that. And I think, through the years, we proved that if you could — you could — I think the other message was that you can fight city hall. It does take a very long time, and it’s very slow and very painful, but you can fight it. And I think that’s what we tried to prove in this case. And ultimately, it was important for us, for final closure, not to just win and walk away; we had to bring that other lawsuit, for violation of his civil rights. That was important for us. That was the exclamation point. It wasn’t about the money, although — the money was only a tangible way of having the FBI saying, “OK, we were wrong,” after all these years. Very hard to make the government say they’re sorry. They don’t say they’re sorry. So what you do is you make them pay some money, and that’s how I guess they say they’re sorry.

AMY GOODMAN: And Geronimo, as you listen to George Bush and Al Gore debate, what do you think, as you watch them run for the presidency.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: Well, I think about all of those years in the hole in prison, dodging bullets, knife thrusts, and the sisters and brothers that are still in there, while all of these demagogic politicians are out here running their mouth and continuing to be a part of this genocidal project program that’s going on that’s killing the movement, the most vibrant, energetic — you know, what we need to continue us on, to keep us continuing on. That’s — my mind is on the comrades in prison mostly, so you’ll forgive me for not being as, you know, well versed in the matters of America’s politics.

AMY GOODMAN: George Bush has presided over more than 140 executions in Texas.

GERONIMO JI-JAGA PRATT: He’s a serial killer.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you for being with us, Geronimo ji-Jaga, Stuart Hanlon, Johnnie Cochran. The new book out on them, Last Man Standing: The Tragedy and Triumph of Geronimo Pratt, by Jack Olsen.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And everyone, every listener, should get that book.

Media Options