Topics

The decision on whether to free former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet is no longer up in the air — but he is. Pinochet is now a free man, flying to Chile aboard a military plane just hours after Britain dropped extradition proceedings against him. Spain, France and Switzerland were among the countries seeking his extradition to try him on charges of torture and other human rights abuses. [includes rush transcript]

British Home Secretary Jack Straw cited Pinochet’s ill health as a reason to release the former dictator, ending a 16-month long battle over whether he should be tried in Spain. There was outrage from human rights organizations and victims, who wanted him tried for human rights abuses committed during Pinochet’s brutal 17-year rule.

Guests:

- Reed Brody, Human Rights Watch.

- Veronica Denegri, survivor of torture under the Pinochet regime and mother of Rodrigo Rojas DeNegri, who was killed by Pinochet’s police in 1986.

Related link:

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The decision on whether to extradite Pinochet is no longer up in the air, although he is. Pinochet is a free man. Britain today dropped extradition proceedings against the Chilean dictator, saving him from extradition to Spain and a trial there for torture. The Home Secretary cited Pinochet’s poor health.

In what may be the last act of a sixteen-month-long legal and human rights battle, Pinochet is a free man. Outrage from Pinochet opponents who wanted him tried for human rights abuses during his brutal seventeen-year rule, in which an estimated 3,000 people were killed or disappeared. Pinochet left the luxury home near London where he had been under house arrest to travel to a waiting Chilean air force plane, where he took off.

We are joined right now by Reed Brody, who is the Advocacy Director for Human Rights Watch. Welcome to Democracy Now!, Reed.

REED BRODY: Hi, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell us the latest news you have and on what grounds Jack Straw, the Home Secretary, released Augusto Pinochet.

REED BRODY: Well, Jack Straw, as you know, ordered medical tests of General Pinochet. He then said he was minded to release the general on the basis of the results of those tests, which nobody had seen. We went into court together with Amnesty International in Belgium to force a release of those tests to the states that were seeking his extradition. Those states unanimously contested the conclusions and argued that there needed to be new tests, or at least that the tests needed to be looked at by a judge.

Jack Straw has rejected those arguments. This morning he released General Pinochet, and he explained that he was doing it because he believed that General Pinochet is unfit to stand trial and that it would do no good to send him to Spain, where — to make that determination, because he had already made that determination.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about appeals? Were people able to appeal before this final decision, and was this a surprise earlier today?

REED BRODY: Well, we certainly weren’t surprised by the decision. Jack Straw had given us indication of which way he was headed. None of the states decided to appeal. Belgium, France, Switzerland, all of whom challenged the medical evidence, felt that, given the Home Secretary’s very wide discretion under British law in matters of extradition, that it would do no good to appeal. In Spain there was a tug-of-war. The investigating judge, Garzon, wanted to appeal, but the Spanish government didn’t want to.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Reed Brody. He is the Human Rights Advocacy Director for Human Rights Watch. Later in the show, we’re going to be talking about the latest shooting in the Bronx, New York, and we’re going to be talking about Bob Jones University.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We continue with Human Rights Watch’s Reed Brody and are also joined by Veronica DeNegri. She is the mother of Rodrigo Rojas DeNegri, who was killed by police in Chile in the 1980s under Pinochet. She is a survivor of torture herself, and she is speaking to us from Washington, D.C.

Again, the latest news. Augusto Pinochet is a free man today. He was saved from extradition to Spain and a trial there for torture by British Home Secretary Jack Straw, who ruled earlier today that he was not fit for trial. Augusto Pinochet then left his luxury home near London, where he has been under house arrest for more than a year, traveled to a waiting Chilean air force plane and took off.

Veronica DeNegri, your response?

VERONICA DENEGRI: As Reed said, in reality, we all knew that that was the direction the extradition was taking. And I don’t consider this a defeat to us, because I believe for many months we put on the first page in the whole world the human rights cruelty and abuses that Pinochet is responsible for. Definitely, that it will be a trial in Chile, I don’t know. I still have big doubts. I hope the new president will do something, but the chances to get justice are very, very rare. I feel that this was a very dirty joke in terms of the health situation of Pinochet.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask Reed Brody of Human Rights Watch, what do you expect to see in Chile? Will there be a trial? Our producer, Maria Carrion, just spoke with attorneys in Chile. Fabiola Letelier, who is the sister of Orlando Letelier, assassinated in the 1970s by Pinochet’s secret police in Washington, as well as other human rights attorneys are, as we speak, in court in Chile calling for the arrest of Pinochet when he touches down there.

REED BRODY: Well, there are currently fifty-nine criminal complaints in Chile against Pinochet for kidnapping, murder, and torture, which were lodged since the arrest in Britain and being investigated by Judge Juan Guzman. Now, General Pinochet has immunity from criminal process as a senator for life. He benefits from an amnesty that he imposed when he was Generalissimo that covers 1973 to 1978. Now, the courts can undo his immunity as a senator for life, and the Chilean Supreme Court has ruled that disappearances that were prolonged and continued after 1978 aren’t covered by the amnesty. So, there is a possibility that he could be tried.

Now, the Chilean government has proposed a constitutional amendment, which would immunize not only General Pinochet, but all heads of state from criminal process after they leave office, in what is a very transparent attempt to protect General Pinochet.

AMY GOODMAN: Would your son — let me ask this question to Veronica DeNegri: would your son, Rodrigo Rojas DeNegri, would his case be brought up in Chile, as well as your own? You’re a survivor of torture yourself.

VERONICA DENEGRI: Oh, definitely. I’m definitely moving to that direction now. I did everything that was possible before in Chile, but I still now, since the cases have reopening, bring it to the judicial courts or system in Chile. Definitely, I am moving in that direction.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you remind our listeners. You have been on a few times, as these different decisions have come down in Britain. What happened to your son in Chile?

VERONICA DENEGRI: My son Rodrigo Rojas DeNegri went back to Chile in 1986. He was taking pictures, like he did here in Washington all those years he was living here. During the time that he was taking pictures in a shantytown in Santiago, he was arrested, along with another young person, Carmen Gloria Quintana, that survived. And both were tortured during the interrogation, and after, both were set on fire.

And they didn’t end there. They, both kids, trying to extinguish their flames, and they were beaten out. And after, they wrapped them in blankets and they went, dumped them on the beach.

It didn’t end there either. The beach was about twenty miles from the area where they were burned. Both kids managed to get out to the road and ask for help. They were brought to a clinic. In the clinic, they did what they could. It was basically take the clothes on their —- the burning areas that were over 62% of their bodies with burns of second— and third-degree. They were sent to the emergency. And in emergency, when Rodrigo entered to the hospital, they collapsed one of his lungs and they deprived him from the medical treatment he deserved.

Carmen was treated, fortunately, and she survived. But it was a long history of things. I remember Human Rights Watch sent a doctor, Dr. Constable, that was able to establish in Congress here in United States the whole meaning of what they did.

I’m sorry, I am very nervous, because I’m living back every moment of this twenty-some years of injustices in Chile.

AMY GOODMAN: I thank you very much for being on with us.

VERONICA DENEGRI: But it’s very important to me that people know that these are crimes that cannot be accepted, not because it happened to my son or because it happened to me. These are not crimes that could be accepted in any part of the world. We have to condemn this. I commit my life, since I was very young, to fight for justice in the world. And I know that I will die fighting for that, and it’s very sad, because when we’re born, our parents always thought that we will have a chance to live a good life.

AMY GOODMAN: Veronica DeNegri, what happened to you in Chile?

VERONICA DENEGRI: Oh, I was arrested. I was badly tortured in many different ways. I was disappeared for a while.

AMY GOODMAN: This was before your son returned to Chile?

VERONICA DENEGRI: Oh, yes —

AMY GOODMAN: Do you feel part —

VERONICA DENEGRI: — this was 1975, '76. After a couple months of being disappeared and reappearing in a concentration camp, Tres Alamos, where I was for some time, along with 181 women. One day, it was decreed that they release me, and they released me with no charges. Nobody, nobody, gave me an explanation. My kids were taken away from me during that period. It took me long, long time to know where they were, what was happening to them. It's something that, you know, nobody have to right to live. And definitely with a sick mind like Pinochet that, to me, is no different than Hitler, and the Condor operation is no different of the expansion of Hitler in Europe.

AMY GOODMAN: Condor meaning the expansion of his brutality beyond Chile —

VERONICA DENEGRI: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: — to Argentina.

VERONICA DENEGRI: Not just Argentina. Uruguay. Bolivia. Brazil.

AMY GOODMAN: Where these countries working with the Pinochet regime —

VERONICA DENEGRI: Yes. Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —- would pick up Chileans and Argentines -—

VERONICA DENEGRI: Definitely.

AMY GOODMAN: — and Chilean, Brazilians, etc.

Reed Brody, what about this larger expansion of Chile, of Pinochet’s brutality, the whole Condor plan.

REED BRODY: You know, just listening to Veronica, it just —- I think of how important this whole case has been. Even today, as General Pinochet goes home, the fact that we have been forced to revisit, or the world has been forced to revisit, that period, United States support for the Pinochet government, Pinochet’s crimes, the fact that Pinochet was arrested, that four countries sought his extradition, that his claim of immunity was rejected, that the kinds of stories that happened to Veronica and her daughter were laid before the British courts -—

AMY GOODMAN: Her son.

REED BRODY: — I think have already changed the way we look at that period and also the way we deal with atrocities in general.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, you have been deeply involved with the case that, would you say was inspired by the Pinochet case? And that’s the case of the former Chad leader, Hissene Habre?

REED BRODY: Very much. Our efforts are so far successful to have the former dictator of Chad, Hissene Habre, indicted in Senegal, is very much patterned on what the Chileans were able to do with Pinochet. The Chadians came to us and said, “Can we do this? Is it really possible to bring somebody like that to justice?” And the Chileans showed that it’s possible in the case of Pinochet. And the Chadians are showing that it’s possible in Africa, as well.

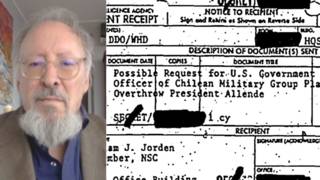

AMY GOODMAN: Recently released documents show CIA involvement and US government involvement in political killings. We have the case of an American, Charles Horman, who was killed as Pinochet came to power, and new documents are showing US knowledge and involvement at some of the highest levels of US officers in Chile at the time. Where will that go, this new information, Reed? Will we see arrests of US officials?

REED BRODY: Well, it would be — I’m not sure if we’re going to see arrests of US officials. But it should at least force us to revisit what our government was doing supporting these kinds of crimes, supporting them and then covering them up, telling US citizens that the government had no idea about what happened to their sons and daughters, when, in fact, the US knew very well. It’s the case with General Pinochet. It’s the case Hissene Habre, who was supported heavily by the United States while he committed crimes against humanity. It’s the case of the Guatemalan leaders who committed genocide against the Indian population in the early 1980s.

I think it’s very important these cases are also a vehicle for examining why we supported these kinds of crimes. It’s not enough — I think it’s important to bring the people that perpetrated them to justice, but it’s also important to look at what our government and what we were doing to support them.

AMY GOODMAN: Veronica DeNegri, I’m going to give you the last word today, as this broadcast goes out around the country. Augusto Pinochet is flying home to Chile a free man. Again, charges, extradition charges, dropped against him by Britain. They said he is too sick to stand trial.

VERONICA DENEGRI: Free man? Yes, in appearance, but I think the soul is not free. And that, to me, is very important. If you don’t have your soul free, no matter how sick you are, you are not free, with big words.

We have a big fight in Chile ahead, longer maybe than what we just past. But I know we will succeed one day. When? I don’t know, but I believe in justice. I believe our right to tell the criminal what he did to us. I believe the right of the families of the disappeared to know what has happened to their loved one, to the families of the executed, like my son, to know why they did it. We have too many questions that have to be answered. And if it’s not Pinochet, somebody has to give it, because this is something that has not involved just Chilean people or South American people. It involves the whole humanity, because when we allow the people in one corner of the world to do these kind of crimes, we are allowing the whole humanity the cruelty and overt abuse of the armed forces when the justice is managed by the armed forces and not by the judicial system.

AMY GOODMAN: Veronica DeNegri, I want to thank you very much for being with us, as well as Reed Brody, of Human Rights Watch. I want to give out some websites. I know the National Security Archives has a lot of newly declassified information about US government involvement in Chile. You can just go on the web, put in National Security Archives. And, Reed Brody, you’re Advocacy Director for Human Rights Watch. What is your website?

REED BRODY: www.hrw.org.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s www.hrw.org.

And, of course, Veronica DeNegri, thank you for being with us and reliving, because I know how painful it is, but you help to make us aware of what our responsibilities are today.

Media Options