Topics

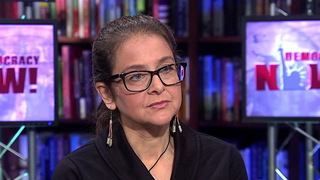

Lori Berenson has been in prison in Peru for more than five years. She was first sentenced to life in prison by a hooded military court in Peru on charges that she was a leader of the MRTA, the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, a group classified as terrorist by the Peruvian government. [includes rush transcript]

For three years, Berenson was held in the frigid Yanamayo prison in the Andes mountains in an unheated, open-air cell without running water, where her hands swelled like boxing gloves from the cold and altitude, and she developed gastric and eye problems. She was later transferred to the Socabaya prison, but there too she was held in complete isolation for many months. It was there that Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman interviewed Lori in March of 1999, herfirst interview with a journalist. We broadcast excerpts a year and a half later when she was moved to a Lima prisonand we felt it was safe to air her words.

Berenson was transferred to Lima after the Peruvian military voided her life sentence and ordered her retried in acivilian court, on reduced charges of collaborating with the MRTA. Lori Berenson continues to deny the charges. Lastmonth, she was convicted and re-sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Just over a week ago, 141 members of the House of Representatives signed a letter to the Peruvian government sponsored by Congresswoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY) urging Lori’s immediate release. New York Senators HillaryClinton and Charles Schumer sent a letter to Peru urging Lori’s immediate release on humanitarian grounds

Yesterday, Democracy Now! broke the sound barrier, when we brought you the voice of Lori Berenson for the first time since she was sentenced to 20 years by a Peruvian court. We had sent Lori Berenson a series of questions and broadcast her answers from the Chorrillos Prison in Lima, Peru.

We continue now with the exclusive interview we first broadcast yesterday. The sound isn’t optimal, but these are the conditions under which she was able to do the interview. We pick up by asking Lori if she thinks that ex-Peruvian President Fujimori and Vladimiro Montesinos played a role in her imprisonment.

Tape:

- Lori Berenson

Related link:

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The State Department yesterday released the results of an investigation, which concludes that the US shared responsibility into the downing of an American missionary plane by a Peruvian fighter jet and a CIA contract airplane on an anti-drug mission in April. The Bush administration suspended the joint anti-drug flights after the shooting, which killed two people, a mother and her baby, but has expressed its desire to resume its cooperation with the Peruvian military as soon as possible.

The Bush administration’s desire to resume ties with the Peruvian military brings little comfort to those working for the release of imprisoned US activist Lori Berenson. Lori Berenson has been in prison in Peru for more than five years. She was first sentenced to life in prison by a hooded military court in Peru on charges that she was a leader of the MRTA, the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, a group classified as terrorist by the Peruvian government.

For three years, Berenson was held in the frigid Yanamayo prison in the Andes mountains in an unheated, open-air cell without running water, where her hands swelled like boxing gloves from the cold and altitude. She was later transferred to the Socabaya prison, but there, too, she was held in complete isolation for many months. It was there that I interviewed Lori in March of 1999, her first interview with a journalist. We broadcast excerpts of that a year and a half later, when she was moved to a Lima prison, and we felt it was safe to air her words.

Well, Lori was transferred to Lima after the Peruvian military voided her life sentence and ordered her retried in a civilian court. They admitted she was not a terrorist leader but were trying her on reduced charges of collaborating with the MRTA. Lori continues to deny the charges. Last month she was convicted and re-sentenced to twenty years in prison.

Just over a week ago, 141 members of the House of Representatives signed a letter to the Peruvian government sponsored by New York Democratic Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, urging Lori’s immediately release. New York Senators Hillary Rodham Clinton and Charles Schumer sent a letter to Peru, urging Lori’s immediate release on humanitarian grounds.

Yesterday, Democracy Now! broke the sound barrier when we brought you the voice of Lori Berenson once again, for the first time since she was sentenced to twenty years by the Peruvian court last month. We had sent Lori Berenson a series of questions and broadcast her answers from the Chorrillos prison in Lima, Peru.

We continue now with the interview we began yesterday. The sound isn’t optimal, but these are the conditions under which she was able to do the interview. We pick up by asking Lori if she thinks that the ex-Peruvian President Fujimori, and Vladimiro Montesinos played a role in her imprisonment. Listen carefully. Again, Lori reads each of our questions out loud and then answers them.

LORI BERENSON: The next question was what role do I think former President Fujimori and Vladimiro Montesinos had in my arrest and initial trial. Oh, I think they had a lot of influence. I think they — I think all trials in military or civilian hooded — courts with hooded judges were political trials that had nothing to do with evidence and a lot to do with politics. In my particular case, yes, my case was a piece that was used as a smokescreen during the entire detention period, the whole reason I was detained when I was detained and throughout my period in which I’ve been in jail.

Do I think the trial of Vladimiro Montesinos might increase the chances that I be released or granted clemency? That’s a difficult one to say. I think there are so many people being put into jail under these corruption scandals, and I don’t know. I still feel the treatment of them in the press and in general is that of people who even see they’ve done wrong and now are even repaying for what they’ve done, or I don’t know. I find it so difficult. It’s really unfathomable to think that someone who has stolen millions and millions of dollars would now say, “Oh, yeah. That was wrong. Please forgive me,” and they’ll probably get out. I really hope that is not the case. But I certainly don’t think this will have a positive effect on me. I think it’s [inaudible] to dissuade public opinion, and they don’t even — to the point that people don’t even see what really is behind, where the real big money is or what the real corruption was about.

Can I talk about the prison where I am housed? What is my relationship with the other women who are imprisoned with me? How do they react to my presence? I don’t know. This is a sort of unusual question. But I am currently being held in a women’s prison in Lima. Prison conditions are probably far worse that in most prisons. In this jail, women were only allowed to use pen and paper since 1999. We’re only allowed to have basically constant access to books since the year 2000. In general, a lot of restrictions that have to do — and also taking into account that in this particular jail most people have lower sentences than any other jails that I’ve been, where most people had life sentences. But, however, the conditions are certainly far — quite brutal, which probably has a lot to do with — to a certain extent, it’s a double crime to be a woman and to be accused of a political crime, because it means that that woman has gone against social standards of being involved in anything, in addition to whatever political issues she was involved in. It’s very notable in the sense of what they’ve done to children. Children visit, you know, once every three months through a mesh screen with no adults present, except with their mothers, I guess. Or a lot of children that were born through — because of rape in police headquarters and then, later, you know, if the woman prisoner wasn’t able to find someone to take care of their child, they would give it to the state. It was a very, very sad situation and very, very harsh situation that they have caused on the children of prisoners. And you can see that to date.

OK, how do I view my case and the publicity it is receiving in comparison to the thousands of other Peruvians who were wrongly tried, tortured and imprisoned under the Fujimori/Montesinos regime? I think my case has been publicized in a more propagandistical way. I think, what is similar to most other cases is the truth doesn’t much come out. Unfortunately, that is a problem to date, because in public opinion there is an image already created. Certainly, there’s more publicity to my case — I would say a lot of negative publicity to my case. I think all Peruvians should have a chance to have the amount of public attention called to their cases, and I would hope that all Peruvians have a greater access to justice than I did. I think that is, they have a greater right than I do to have that justice.

Have I sustained my optimism when I see the conditions of the people around me? I think it has to do with the optimism that I see in those who are in such horrendous conditions, that in spite of the years of detention and the torture that many have been submitted to and the suffering that people’s families have gone through — a lot of family members detained, a lot of others who are widows, or others who have family members who have been killed, have been persecuted — it’s a situation that creates moral strength, and I think it would be wrong for me not to — not to — I think one has to stand tall in spite of that; not give any last — I have a [inaudible] this in English, a little gusto, basically have the government achieved defeating one morally, and I think, in that sense, it’s been very powerful, a very interesting experience, a very noble experience to have met, at this point, many, many people in jail, who have just stood tall whatever their beliefs are. I think that’s very important.

What sort of support do I think I have in Peru, and how do I explain this? I would say in Peru there is a lot of confusion about me, as there is a lot of confusion about everything that has happened in the country over the last ten years, as I’ve explained, for the policy of disinformation. I believe that at some point cases, as mine and many others, will be seen in another light if they are seen within their true dimension. And I hope that happens soon.

Do I think any of the sentiment in Peru against me is motivated by a feeling that Peru is being pressured by the US government? I think that could be a factor. I believe that what Fujimori — Fujimori also used that, when he said, “No. We’re not going to go soft on terrorism. Basically, we’re not going to listen to the imperialists,” and that kind of thing. I mean, it was part of a propaganda kind of thing. At this point, there could be an honest sentiment of that, and I would certainly understand that. I think all Peruvians have a right, actually a greater right than I do, to have justice. I think it’s more their right than it is my right. So I would hope it would be understood that it is not my desire to have special conditions or special privileges that others don’t have. To the contrary, I would prefer that everybody have those conditions. I think that is what actually Peru needs.

Do I think that some of the feelings of the Peruvian people towards me might be colored by their attitudes toward the United States, which supported Montesinos and Fujimori for many years? I don’t know. But I do believe it could be interpreted within this sort of anti-North American sentiment, which also has a lot to do with the economic policies that have directly affected Peruvians, as in all Latin American peoples.

Every news article has said that your second trial was brought about by years of US pressure. In fact, what have the Clinton and Bush administrations done on my behalf? Have I ever been visited by a US ambassador to Peru? In terms of US pressure, I think US pressure has to do with the fact — one of the factors has to do with the new trial. I think US pressure has a lot to do with the constant efforts of family and friends to make my situation known in the United States. No, I’ve never been visited by a US ambassador to Peru.

Given that the US government is so close to the Peruvian government and military, providing it with millions of dollars in weapons and training, do I think that if the US government really wanted me released that I would be free? I probably shouldn’t answer this question, so I’ll just leave it there. I certainly have opinions, but it might not be as well understood as I would like it to be.

OK, with respect to the question, “What would I say to a young person just beginning a life of activism? What would I tell him or her about the risks and rewards of working for social justice?” well, the first thing I would do is I’d be — I am always extremely pleased to hear how young people, in spite of — basically, I would say that the new economic policies that are presently in effect in the world have a tendency of fomenting or promoting a very individualist way of thinking. I believe that those who are able to realize that aspect and to look beyond what society tells them to look at are people who already have a great social conscience of what morally we are ….moral obligation we all have, all human beings have, to do something. I would tell other people that it’s really important that all people unite to work for a better society. I think it might have its cost in terms of personal sacrifice and sacrifices of many, many people. But if we don’t, if the new generations and the — I mean, if in general people don’t work to that end, I think society will actually get much worse in terms of poverty, in terms of destruction of the environment, which all has to do with poverty and has to do with how that will reflect on greater poverty and greater suffering of human beings.

There are so many things with globalization, you just the sense — I know it’s something that has gotten — I guess it’s been a — it’s a more, I would say, popular topic since I’ve been in jail. But what I do have the sense of is that, basically, the interrelation of poverty, hunger, on one hand, illnesses, destruction of the environment, violations of human and fundamental rights, is basically a globalized phenomenon. I think it’s very important that people work towards that. It will be a hard uphill battle, but it certainly is something absolutely necessary if we want to look towards the continuation of the human race and any prospectus of greater social justice for the majorities that are actually seeing themselves more impoverished every day.

AMY GOODMAN: Lori Berenson speaking from the Chorrillos prison in Lima, Peru, breaking the sound barrier. She has not had access to a radio or television reporter since her sentencing. If you would like to get more information on her case, you can go to the website www.freelori.org. We’ll be playing you the last part of this exclusive interview tomorrow.

Media Options