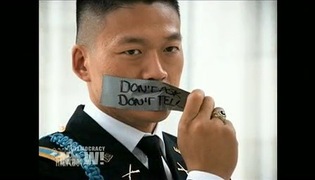

The military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy has led the Pentagon to fire 37 Arabic translators at a time when the military needed them more than ever. We talk to Nathaniel Frank, senior research fellow at the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military at the University of California, Santa Barbara. [Includes transcript]

A recent post in the Washington Post began:

Kathleen Glover was cleaning the pool at the Sri Lankan ambassador’s residence recently when she heard the sound of Arabic drifting through the trees. Glover earned $11 an hour working for a pool-maintenance company, skimming leaves and testing chlorine levels in the backyards of Washington. No one knew about her past. But sometimes the past found her.

Glover recognized the sound instantly. It was the afternoon call to prayer coming from a mosque on Massachusetts Avenue. She held still, picking out familiar words and translating them in her head.

She learned Arabic at the Defense Language Institute (DLI), the military’s premier language school, in Monterey, Calif. Her timing as a soldier was fortuitous: Around her graduation last year, a Government Accounting Office study reported that the Army faced a critical shortage of linguists needed to translate intercepts and interrogate suspects in the war on terrorism.

“I was what the country needed,” Glover said.

She was, and she wasn’t. Glover is gay. She mastered Arabic but couldn’t handle living a double life under the military policy known as “don’t ask, don’t tell.” After two years in the Army, Glover, 26, voluntarily wrote a statement acknowledging her homosexuality.

Confronted with a shortage of Arabic interpreters and its policy banning openly gay service members, the Pentagon had a choice to make.

Which is how former Spec. Glover came to be cleaning pools instead of sitting in the desert, translating Arabic for the U.S. government.

In the past two years, the Department of Defense has discharged 37 linguists from the Defense Language Institute for being gay. Like Glover, many studied Arabic. At a time of heightened need for intelligence specialists, 37 linguists were rendered useless because of their homosexuality.

To discuss this, we are joined by Nathaniel Frank, senior research fellow at the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Nathaniel Frank, senior research fellow at the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is also an adjunct professor of history at New York University and New School University.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we are joined right now by someone who has looked closely at this issue, Nathaniel Frank. He is a senior research fellow at The Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and an adjunct professor of history here in New York at New York University and New School University. Welcome to Democracy Now!.

NATHANIEL FRANK: Hi.

AMY GOODMAN: The significance of this, the story just coming out now, and can you explain what is happening?

NATHANIEL FRANK: Well, the story is not just coming out now, but it’s been updated since we now have this number of 37 linguists having been fired under the policy at a time of heightened national security. And last year when the story first came out, to take one example, the Army had 84 slots to fill of Arabic translators and could only fill 42 of them. So if you take this number, 37, it’s a very high number of slots that could have been filled that the government is deciding shouldn’t be filled because it’s insisting on enforcing an outdated policy.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain exactly what the policy is today.

NATHANIEL FRANK: The policy, which has become known as “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” requires that gay people refrain from expressing their sexual identity or engaging in any sort of homosexual conduct, which means essentially that they need to remain silent about their identity and celibate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, on and off base, which is obviously not a regulation applied to straight soldiers. So the other part of the policy is the military is not supposed to ask or investigate without credible evidence that a service member is gay—which has not always been the case. But that’s the “don’t ask” part of it.

AMY GOODMAN: And has there been a case where the military is fully aware that someone is gay, but they allow them to remain?

NATHANIEL FRANK: Absolutely. And what we find is that during war time, the military’s discharge figures almost always go down— ever since Vietnam and probably beforehand, but Vietnam is when we have statistics about that. Every year since “Don’t ask, don’t tell” was implemented in 1994, after the debates in '92 and ’93, the discharge figures have gone up, until 2002, the year that we are fully at war. That year, for the first time, the discharge figures went down. So there's a certain amount of discretion that commanders have, even though the law stipulates that they have to investigate and then discharge gay people. There’s a certain amount of discretion that commanders have. For instance, they can simply say this statement of homosexuality is non-credible. And essentially they’re saying when someone comes to them and says I’m lesbian, they will say, no, you’re not, get back to work. There’s a process by which people have to give documentation from their parents and friends and so forth, trying to prove that they’re gay.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m looking at the Washington Post piece. It says that the Army says that the discharged linguists were casualties of their own failure to meet a known policy. “We have standards,” said Harvey Parrot, a spokesman for the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command at Ft. Monroe, Virginia. “We have physical standards, academic standards, there’s no difference between administering these standards and administering “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” The rules are the rules.”

NATHANIEL FRANK: What he didn’t say here is what the standards are vis-a-vis gay soldiers. Even Colin Powell acknowledges that gay soldiers can be fine soldiers, and that they themselves are not the problem. In fact, the rationale for this policy at this point—and the rationale has shifted over the years as each rationale has been dismantled. But the rationale currently is that it’s the discomfort of straight soldiers which requires that gay soldiers be discharged, and that if it’s known that soldiers are gay, that straight soldiers will be uncomfortable and that will be a detriment to unit cohesion and combat effectiveness. There’s actually not a shred of evidence to that at all. Our center has done extensive studies in Britain, Israel, Canada and Australia, on what happened over the past ten years when those countries each lifted their bans. What we have found was exactly what people expected to find, was that it’s a non-issue, and that there is no correlation between the presence of known gay soldiers and any impairment of military effectiveness. So, the standards that he’s referring to are certainly not standards that have anything to do with military effectiveness, and have much more to do with prejudice and with the tradition of insisting that homosexuality is incompatible with military service. Even Dick Cheney has called that rationale that gays are a threat to national security a bit of an old chestnut.

AMY GOODMAN: Dick Cheney’s own daughter is a lesbian.

NATHANIEL FRANK: Yes, she is. And I think that that may curb some of the vehemence of the sentiment against gays, but he certainly hasn’t taken any position that has facilitated the ending of this ban, or the—.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you see it changing at all?

NATHANIEL FRANK: I do see it changing. I think, you know, we — we debate this issue often and sometimes people actually ask us to help find people who will debate the other side. We have a lot of trouble debating the other side. There are people out there, but very few people will come to the defense of this policy. I think the next time it’s debated in earnest, when the political winds shift slightly or if there’s another court case or, god forbid, another dramatic incident of harassment or beating, that the country will look anew at this policy and see that there’s no evidence supporting its necessity and that, in fact, it’s becoming clear that it’s detrimental to national security, not just unnecessary.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much for being with us. Nathaniel Frank, senior research fellow, Center for Sexual Minorities in the Military, University of California, Santa Barbara, and adjunct professor at New York University and New School University. Your website —

NATHANIEL FRANK: I hope I know it — gaymilitary.ucsb.edu

AMY GOODMAN: Thank you for joining us.

NATHANIEL FRANK: Thanks for having me in.

Media Options