Topics

Chilean poet and Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda would have turned 100 years old this week. We speak with poet and professor Martin Espada who teaches creative writing, Latino poetry, and the work of Pablo Neruda. He recently returned from Chile where he was invited to participate in the celebration of the Neruda centenary.

Chilean poet and Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda would have turned 100 years old this week. Fellow Nobel Prize-winner Gabriel Garcia Marquez called Pablo Neruda the “greatest poet of the 20th century — in any language.” This week, many Chilean towns and cities have been staging poetry readings to mark Neruda’s centenary.

Born the son of a railway worker, Neruda began writing poetry when he was 14 years old and didn’t stop until his death in 1973.

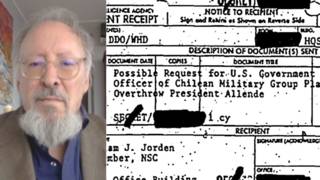

A long-standing Communist Party supporter, he died less than two weeks after Gen Augusto Pinochet overthrew Salvador Allende’s government in a U.S.-backed coup. His funeral became the first public show of opposition to Chile’s military rulers and his work was banned until 1990 under the Pinochet regime.

In his Memoirs, Neruda writes: “Poetry is a deep inner calling in man; from it came liturgy, the psalms, and also the content of religions. The poet confronted nature’s phenomena and in the early ages called himself a priest, to safeguard his vocation…Today’s social poet is still a member of the earliest order of priests. In the old days he made his pact with the darkness, and now he must interpret the light.”

- Martin Espada, poet and professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst where he teaches creative writing, Latino poetry, and the work of Pablo Neruda. Sandra Cisneros calls Espada the “Pablo Neruda of North American authors.” Others have called him “The Latino Poet of his Generation.” He is the winner of the American Book Award, among other honors. He is the Poet Laureate of Northampton, Massachusetts. He recently returned from Chile where he was invited to participate in the celebration of the Neruda centenary.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: As we turn now to an anniversary of sorts, Chilean poet and Nobel Laureate Pablo Neruda would have turned 100 years old this week. Fellow Nobel Prize-winner Gabriel Garcia Marquez called Pablo Neruda the, quote, greatest poet of the 20th century, in any language. Born the son of a railway worker, Neruda began writing poetry when he was 14 years old, didn’t stop until his death in 1973. A long-standing Communist Party supporter, Pablo Neruda died less than two weeks after General Augusto Pinochet overthrew Salvador Allende’s government in a U.S.-backed coup. His funeral became the first public show of opposition to Chile’s military rulers. His work was banned until 1990 under the Pinochet regime. This week, many Chilean towns and cities have been staging poetry readings to mark Neruda’s centenary while restaurants have prepared special menus based on his “Odes To The Onion.” We’re joined right now by Martin Espada, poet and professor at the University Of Massachusetts, Amherst, teaching creative writing, poetry and the work of Pablo Neruda, has just returned from Chile. Welcome to Democracy Now!

MARTIN ESPADA: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Great to have you with us. What was happening in Chile around this 100th anniversary of the birth of Pablo Neruda?

MARTIN ESPADA: Oh so many things. There was a celebration sponsored by the government of Chile and, in fact, I was invited to Chile by a Presidential commission set up for that purpose. But there was also popular celebration throughout Chile, which really manifested itself most clearly at Isla Negra, perhaps the most famous writers’ house in the world, belonging to Neruda. This past Sunday, the day before his 100th birthday, an extraordinary gathering took place there and I was very fortunate to be there, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about Pablo Neruda’s significance?

MARTIN ESPADA: I agree with the assessment of Gabriel Garcia Marquez that he was the greatest 20th century poet for any language. There really is a Neruda for everyone, there’s Neruda the love poet, Neruda the surrealist poet, the poet of historical epic, Neruda the political poet, Neruda the poet of common things, with the odes, the poet of sea and so on. But throughout it all, we see with Neruda, first of all, a great compassion for other human beings, no matter which phase of his career we’re talking about. And secondly, a deep appreciation of the fact of being alive, which again we see at every stage for Neruda.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Martin Espada, who has taught for many years the work of Pablo Neruda and just returned from Chile where there is a national celebration going on about the life of Pablo Neruda. What about the period at end of his life, what he understand was happening in Chile as he died less than two weeks after Pinochet rose to power?

MARTIN ESPADA: Neruda’s death is inseparable from the coup that took place of course September 11, 1973, the first September 11. And at the time, Neruda was very ill with prostate cancer. Certainly the coup hastened his death. He was aware what was going on. He was aware of the destruction of Chile, the destruction of his vision for a socialist Chile and, of course, the death of many friends, including Salvador Allende. So these things became inseparable: Neruda’s death and the death of democracy in Chile. It’s significant that when Neruda died, his widow, Matilda, brought his body to lay in state at another one of his houses called 'La Chascona' in Santiago. She did this specifically because the military had trashed the house and she wanted the world to see what was going on with the 'La Chascona', the house in Santiago, but also what was happening with the coup in Chile at the time.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes, there were other September 11ths, September 11, 1973 is a day Salvador Allende died in the palace in Chile as the Pinochet forces rose to power. And as you are teaching Pablo Neruda, when you are first introducing students, is there a poem that you share with them or an excerpt or a book that you recommend they go to first?

MARTIN ESPADA: Well, I teach Neruda, according to the chronology of his life. It is a very easy thing to do because his poetry reflected his life so closely in so many ways. Certainly we often gravitate to Neruda, the political poet and certainly there is no greater political poem than his masterpiece, “The Heights of Maccu Picchu.” Neruda visited the ruins of the Inca city in the Andes In Peru in 1943 and subsequently wrote a book-length poem in 12 parts, celebrating the achievement of Maccu Picchu, but also condemning the oppression, the slavery, which made it possible and ultimately in the 12th Canto, calling upon the dead, centuries of the dead to be born again and to speak through him.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s hear a clip of that poem. Actually read by Pablo Neruda, Alturas del Maccu Picchu. [Pablo Neruda speaking in Spanish].

AMY GOODMAN: Pablo Neruda, reading from his poem Alturas del Machu Picchu. A special thanks to the Pacifica Network Radio Archives that has collections of his readings as well as tens of thousands of other recordings. Very loose translation of this section of this epic poem. Martin Espada.

MARTIN ESPADA: Well, Neruda realizes, once he comes to the heights of Machu Picchu, that this magnificent achievement has been built on what he calls a groundwork of rags and there’s a turning point in the poem where he essentially accuses the city, confronts the city with these questions about the slaves that were buried there. And you can hear the passion in his voice at this point in the poem. You know, there is a real powerful indignation there. And what becomes clear, you can hear from the tone of his reading, is that there’s a very, very close association between Pablo Neruda’s poetry and the idea of justice. And the people of Chile today, even now, associate Pablo Neruda with the idea of justice. I saw something —

AMY GOODMAN: Five seconds.

MARTIN ESPADA: Saw something really extraordinary at Isla Negra when I was there. A gathering of the families of the disappeared and the detained who came to his tomb with photographs and placards.

AMY GOODMAN: Martin Espada, we have to leave it there. I want to thank you very much for joining us.

Media Options