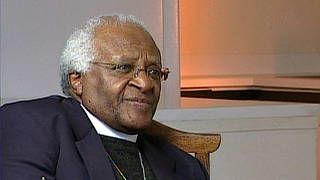

On the day of announcement of the Nobel Peace Prize, we play an interview with another Nobel Peace Prize winner — Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Earlier this week he turned 75 years old. [includes rush transcript]

We end today’s show with the words of South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu. In 1984 Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize. At the time he was at the forefront of the anti-apartheid campaign. Earlier this week he turned 75 years old. Over one thousandspeople, including Nelson Mandela, gathered in Johannesburg to pay tribute to the man.

A new biography on Desmond Tutu has just been published. It is titled “Rabble Rouser for Peace.” I had the opportunity to interview Desmond Tutu two years ago. He was visiting New York for a reading of the play Guantanamo at the Culture Project. I began by asking him for his response to what is happening at Guantanamo.

- South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: I had the opportunity to interview Archbishop Desmond Tutu two years ago. He was visiting New York for a reading of the play, Guantanamo, at the Culture Project. Again, it was written by Robyn Slovo’s sister, Gillian Slovo, and Victoria Brittain. I asked him for his response to what is happening at Guantanamo.

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: For someone coming from South Africa, you [inaudible] that’s exactly what they were doing for exactly the same reasons that they gave. When you said, “Why do you detain people without trial? Why do you ban people as you are doing?” And the response from the South African government was, “Security of the state.” And anyone who questioned it would then be regarded, especially if you are white, as being unpatriotic.

And I just want to say to you: Is this something that you want done in your name? Isn’t it time there was a same sense of outrage that people had about apartheid, which people should have had about the Holocaust? What would happen if it was Americans held by some other country under these conditions? The point is, God has actually got no one. The God we worship is strange. They say this God is omnipotent, but God is also very weak. There’s not a great deal that God seems to be able to do without you.

AMY GOODMAN: During your years in South Africa before the end of apartheid, you were a deep advocate of nonviolence, yet you saw so many detained, so many killed. What do you feel, and what did you feel then? How did you make it through those days? What did you advocate? How did you stick to your principles of nonviolence?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: One of the wonderful things actually is — I’ve got to speak as a Christian — is belonging to the church and knowing that you belong to this extraordinary body. When things were really rough, it’s wonderful to recall for me now, that I sometimes got, when the South African government had taken away my passport, I got passports of love from Sunday school kids here in New York, and I plastered them on the walls of my office. But although I couldn’t travel, hey, here were all of these wonderful people all over the world. And I had a — I met a nun in New York at a particular time, and I asked her, “Can you just tell me a little bit about your life? How do you” — and she said, “Well, I am a solitary. I live in the woods in California. I pray for you. My day starts at two in the morning.” And I said, “Hey, man! I’ve been prayed for at two in the morning in the woods in California. What chance does the apartheid government stand?” So, one was being upheld.

And, you know, when frequently you say to people, the victory that we won against apartheid — a spectacular victory — that would not have happened without the support of the international community, without the support of people like yourselves, without the support of those who were students at the time who might have been crazies, but they were fantastic in their commitment. And in this country, actually, they showed that you could in fact change the moral climate, because at the time the Reagan administration was totally opposed to sanctions, and students, but not just students, the many, many people who were prepared to be arrested on our behalf, who demonstrated on our behalf, who boycotted on our behalf, well, they changed the moral climate to such an extent that Congress passed the anti-apartheid legislation, and they even managed a veto override, which was fantastic.

And so, I just happened. I always say I was a leader by default, because our real leaders were either in jail or in exile, and sometimes when people say, “And he got the Nobel Peace Prize,” I say, “Well, actually, you know, it was that they thought maybe it was time it was given to a black.” And, ah, he has an easy surname: Tutu. Tutu. Imagine. Imagine if I had a surname like Waokaokao.

AMY GOODMAN: Archbishop Tutu, how do you feel —- how do you feel about -—

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: You can’t pronounce that.

AMY GOODMAN: How do you feel about the invasion and occupation of Iraq?

ARCHBISHOP DESMOND TUTU: It was fantastic seeing the many, many people who came out in opposition. It was fantastic. You know, sometimes when you say, “Ach, Americans,” or “Oww, people nowadays don’t care,” it’s not true. Millions turned out. Millions. Millions said, “No. Give peace a chance.” And I said, and so many others — I wasn’t the only one. The Pope said so, too. The Archbishop of Canterbury said so. The Dalai Lama said so.

But this war, if it was to be a justifiable war in terms of the just war theory, would have to be one that was declared by a legitimate authority. And the administration here was aware of that. That’s why they went to the UN. There’s no point in going to the UN, if you had already decided — they probably, of course, had decided — but, I mean, there was no point unless they believed or they realized in order for it to be legitimate and therefore justifiable, the only authority would have to be the UN. And when they didn’t get what they wanted from the UN, they did what they did. We said then, and we keep saying so, not just that it was illegal, it was immoral. And the consequences of it just now — I mean, you have to be — you’ve really got to be blind to say, “Well, yeah, it’s okay. We have removed Saddam Hussein.” Why didn’t you say that was the reason for going? Because the world would have said, “No, no, no, no. That isn’t a reason that will be allowable for you to declare war.”

And I’m sad. I’m sad that we seem so inured now. They tell you a hundred people have been killed, and the United States and its allies are doing that; and they say, “No, no. We targeted that house, because our intelligence said so.” Intelligence. The same intelligence that said there were weapons of mass destruction? Please. That’s been done in your name, that mothers and children have been killed. And when you say, “What about the civilian casualties?” They say, “Sorry, our intention was to target insurgents.” And most of us, I think, just shrug our shoulders. But you see, you experienced a little bit on September the 11th, the kind of thing that is meted out on a regular basis.

AMY GOODMAN: Archbishop Desmond Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize. He’s from South Africa, turned 75 this week.

Media Options