Canadian citizen Maher Arar announces he will “most likely” be appealing a recent U.S. federal court ruling to dismiss his lawsuit challenging the U.S. government policy known as extraordinary rendition. The judge, David Trager, said he could not interfere in the case because it involves crucial national security and foreign relations issues. [includes rush transcript]

A U.S. federal judge has dismissed a lawsuit filed by a Canadian citizen against the U.S. government for detaining him and sending him to Syria where he was jailed and tortured. Maher Arar was the first person to mount a civil suit challenging the U.S. government policy known as extraordinary rendition.

In October 2002, he was detained at JFK airport while on a stopover in New York. He was then jailed and secretly deported to Syria. He was held for almost a year without charge in an underground cell not much larger than a grave. Charges were never filed against him.

In a ruling earlier this month, the federal judge, David Trager, said he could not interfere in the case because it involves crucial national security and foreign relations issues. In an 88-page judgment, Trager wrote “One need not have much imagination to contemplate the negative effect on our relations with Canada if discovery were to proceed in this case and were it to turn out that certain high Canadian officials had, despite public denials, acquiesced in Arar”s removal to Syria.”

The Center for Constitutional Rights launched the lawsuit on Arar’s behalf in January 2004 against former attorney general John Ashcroft and other U.S. officials, seeking undisclosed damages.

Maher Arar joins us on the line from his home in Canada.

- Maher Arar, filed a lawsuit against the U.S. government for detaining him and sending him to Syria where he was jailed and tortured. He was the first person to mount a civil suit challenging the U.S. government policy known as extraordinary rendition.

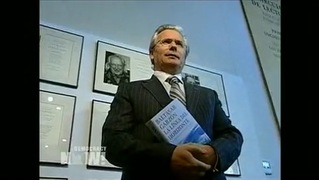

- Michael Ratner, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Previous Democracy Now! coverage of Maher Arar:

- Maher Arar Fights to Keep Torture Suit Against U.S. Government Alive

- U.S. Claims Maher Arar “Extraordinary Rendition” Lawsuit Jeopardizes National Security

- Amnesty Calls for Release of Syrian Canadian Jailed in Damascus for Over 2 Years

- Canadian Man Deported by U.S. Details Torture in Syria

- Canadian Citizen Deported to Syria By U.S. Returns Home to Montreal After Spending A Year in Damascus Jail

- Canada Warns Its Citizens About Traveling in the United States: Advisory Comes After U.S. Officials Secretly Detain a Canadian Citizen and Deports Him to Syria, Where He Hasn’t Lived in 14 Years

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Maher Arar was the first person to mount a civil suit challenging the U.S. government policy known as “extraordinary rendition.” In October 2002, he was detained at JFK Airport while on a stopover in New York. He was then jailed, secretly deported to Syria. He was held for almost a year without charge in an underground cell not much larger than a grave. Charges were never filed against him.

In a ruling earlier this month, the federal judge, David Trager, said he could not interfere in the case because it involves crucial national security and foreign relations issues. In an 88-page judgment, Trager wrote, quote, “One need not have much imagination to contemplate the negative effect on our relations with Canada if discovery were to proceed in this case and were it to turn out that certain high Canadian officials had, despite public denials, acquiesced in Arar’s removal to Syria.”

The Center for Constitutional Rights launched the lawsuit on Arar’s behalf in January 2004 against former attorney general John Ashcroft and other U.S. officials, seeking undisclosed damages.

Maher Arar joins us on the line right now from Ottawa. Michael Ratner is still in the studio with us from the Center for Constitutional Rights. Welcome to Democracy Now!, Maher Arar.

MAHER ARAR: Thank you for inviting me.

AMY GOODMAN: Your response to the judge’s dismissal of your case?

MAHER ARAR: Well, it was quite shocking. I was not expecting him to dismiss the entire case. All I can say is that in his ruling it seems that the court system is risk of becoming complicit with the Bush administration when it comes to torture.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you explain briefly what did happen to you, how you ended up in the U.S. government’s hands at JFK Airport?

MAHER ARAR: Well, I had traveled to the States before I had worked in the States. I was not expecting anything really that serious to happen. I was stopped and asked routine questions at the beginning. I cooperated fully. Of course, they denied — they didn’t want — didn’t allow me to make a phone call. But all of a sudden they, you know, after two days of intense interrogation, they chained and shackled me and took me to the Metropolitan Detention Center and, you know twelve — ten days later, they just secretly deported me to Syria, without having — they didn’t — I mean, I was not afforded any kind of due process. I was not afforded the basic rights of — I do not want to say “an American” — the basic rights of a human being.

AMY GOODMAN: What did they do to you in Syria?

MAHER ARAR: Well, you know, they sent me to a country where it is common knowledge that they torture detainees. I was — I spent there a year, ten months of which I was placed in an underground cell. Of course, this is not to mention the beatings, the physical beatings I endured at the beginning when I arrived in Syria. But I can tell you that the psychological torture that I endured during this ten-month period in the underground cell is really beyond human imagination. It is beyond human imagination. I wanted — through my lawsuit, I wanted to hold these people accountable for what they did to me. But, unfortunately, the judge dismissed the entire case. It is really sad.

AMY GOODMAN: Michael Ratner, what about the rationale that the judge used to dismiss thiscase?

MICHAEL RATNER: You know, this was one of the most remarkable and infamous and worst decisions I’ve ever read by a federal judge. I mean, what it really is saying is it gives a green light to the U.S. to take people like Maher Arar and send them overseas for torture. You understand that he had to accept the allegation that the United States government, the Bush administration, intentionally sent Arar over to Syria to be tortured. And on that allegation, he said, “We cannot go into this case because of national security.”

And even worse, in my view, even worse, he wrote an opinion that said it might be one thing to torture somebody for purposes of getting evidence for a criminal case; “that,” he said, “I agree is unconstitutional, but it’s not yet sure under the Constitution or it’s still an open question of whether if you torture someone for purposes of preventing terrorism, whether that is unconstitutional.” In other words, he is buying into the argument, buying into it that you might be able to torture people if your purpose is to prevent terrorism. This is coming from a federal judge.

What’s happened here is the idea that torture is somehow a legitimate means in the so-called war on terror is now seeping into not just the administration and the executive, into the judiciary, into obviously the pundits and everything else. It is one of the most — I mean, I was incredibly flabbergasted when I read that. In other words, you can torture for one reason, but you can’t torture for another. What else do we have to say? This is Pinochet. This is Pinochet saying I can torture in the name of national security, and this is our client on the phone, Maher Arar, who had this happen to him, who was sent to a place by the United States to be tortured.

AMY GOODMAN: We wanted to go for a minute to Alfred McCoy. We interviewed him a few days ago. He’s a professor of history at University of Wisconsin, Madison, and author of A Question of Torture: C.I.A. Interrogation, From the Cold War to the War on Terror. The book gives an account of the C.I.A.’s secret efforts to develop new forms of torture, spanning a half-century. This is a clip of what Professor McCoy had to say.

ALFRED McCOY: Now, this produced a distinctively American form of torture, the first real revolution in the cruel science of pain in centuries, psychological torture, and it’s the one that’s with us today, and it’s proved to be a very resilient, quite adaptable, and an enormously destructive paradigm.

Let’s make one thing clear. Americans refer to this often times in common parlance as “torture light.” Psychological torture, people who are involved in treatment tell us it’s far more destructive, does far more lasting damage to the human psyche than does physical torture. As Senator McCain said, himself, last year when he was debating his torture prohibition, faced with a choice between being beaten and psychologically tortured, I’d rather be beaten. Okay? It does far more lasting damage. It is far crueler than physical torture. This is something that we don’t realize in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Professor Al McCoy. Maher Arar, from your experience of being held for almost a year in Syrian jail, your response?

MAHER ARAR: Well, I do agree 100% with what I just heard. I can tell you, for example, during the first two weeks of my stay in Syria, I was physically beaten. What happened during this initial period is I just wanted them to leave me alone, even in that dark and damp underground cell. But after a while, the psychological torture that I endured during this lengthy period, I was ready — I was ready, especially by the end of my stay, by the end of the ten-month period in this underground cell, I was ready, frankly, to confess to anything. I would just write anything so that they could only take me from that place and put me in a place where it is fit for a human being. I was — not only that, I was ready to endure more physical beatings, more physical beatings just to get rid of this place.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did —

MAHER ARAR: And I do agree 100% with what — it’s a personal experience I lived, and I think if you ask other torture victims who have been psychologically tortured, they will tell you the same thing.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, what did you confess to?

MAHER ARAR: Well, the false confession was, frankly, at the beginning. They wanted me to say that I’ve been to Afghanistan, which I ended up saying anyway. But what I’m referring to here, even by — after ten months of that psychological torture, if they asked me to sign another false confession, and they told me, “Listen, if you sign this, we will take you to a different place where you could live as a human being,” I would have signed anything.

AMY GOODMAN: The effects on you today, Maher Arar? You have been released. You haven’t been charged. But the effects of what happened to you in Syria?

MAHER ARAR: You know, I’m completely a different person. I still have fears. I don’t take the plane anymore. I don’t fly. I lost confidence in myself. I feel overwhelmed. My — there is some kind of emotional distancing between me and my kids and my family. They ruined my life. They ruined my life, and I have not been able to find a job. People try to — you know, some people I know, they try to distance themselves from me. It’s — you know, I don’t know how to describe it. I don’t think there is any word I could use to describe what I am going through. And I thought when I came back it would take me a month or two months or a year or two years to get back to normal life. It has been two years and four months since I came back to Canada, and there are things that are improved a little bit, but I’m still not the same person, and I’m still suffering psychologically.

AMY GOODMAN: Will you appeal the decision?

MAHER ARAR: One thing I know is I’m not going to give up, whether it’s through appealing or some other process. I have not discussed the details with my lawyers yet, but apparently and most likely we’re going to be appealing the decision.

AMY GOODMAN: Maher Arar, I want to thank you very much for joining us from your home in Ottawa, Canada, and Michael Ratner, President of the Center for Constitutional Rights, that has taken on Maher’s case. The Center has put out a new book. It’s called Articles of Impeachment Against George W. Bush.

Media Options