Related

Topics

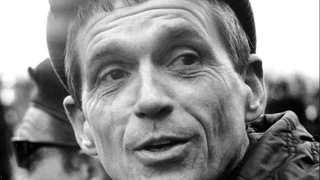

We speak with Father Daniel Berrigan, one of the country’s leading peace activists of the past half-century. Hundreds of people are gathering in New York this weekend to celebrate his 85th birthday. We discuss his life as a Jesuit priest, poet, pacifist, educator, social activist, playwright and lifelong resister to what he calls “American military imperialism.” [includes rush transcript]

Our next guest is one of the country’s leading peace activists of the past half-century.

In 1968, he traveled to North Vietnam with Howard Zinn to bring home three U.S. prisoners of war.

Later that year he made national headlines when he and eight others burned draft files in Catonsville Maryland.

In 1970 he spent four months living underground as a fugitive from the FBI.

In the early 1980s he helped launch the international anti-nuclear Plowshares movement when he and seven others poured blood and hammered on warheads at a GE nuclear missile plant in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

I am talking, of course, of Father Daniel Berrigan. Jesuit priest. Poet. Pacifist. Educator. Social activist. Playwright. Civil rights activist. And lifelong resister to what he calls “American military imperialism.”

Along with his late brother, Phil, Dan Berrigan played an instrumental role in inspiring the anti-war and anti-draft movement during the late 1960s as well as the anti-nuclear movement.

Georgetown University theology professor Chester Gillis has said of Father Berrigan: “If you were to identify Catholic prophets in the 20th century, he’d be right there with Dorothy Day or Thomas Merton.”

This weekend, hundreds of people are gathering in New York to celebrate his 85th birthday.

In a moment we will speak with Father Berrigan but we begin by going back 35 years to the documentary “The Holy Outlaw” by director Lee Lockwood. It features Daniel Berrigan as well as the historian Howard Zinn.

- “The Holy Outlaw”–excerpt of documentary by director Lee Lockwood.

Father Dan Berrigan joins us live in our firehouse studio.

- Fr. Daniel Berrigan, Jesuit priest and social activist. He is a prolific writer of poetry and the author of more than 30 books. He recently turned 85 years old.

AMY GOODMAN: Father Daniel Berrigan, welcome to Democracy Now!

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: I assume you’re about your mother’s age, now, that we were watching in the film. How is it to see her there?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Well, it’s always moving, because she was so clear. And she was so clearly on our side when very few would be.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about that first decision you made in Catonsville, before Catonsville, to do it, what you were doing at the time, and how you made the decision?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yeah. I was teaching at Cornell, and Philip came up. He was awaiting sentencing for a prior action in '67 in Baltimore, where they poured their blood on draft files in the city. And he came up to Cornell and announced to me, very coolly, that he and others were going to do it again. I was blown away by the courage, and the effrontery, really, of my brother, in not really just submitting to the prior conviction, but saying, “We've got to underscore the first action with another one.” And he says, “You’re invited.” So I swallowed hard and said, “Give me a few days. I want to talk about pro and cons of doing a thing like this.” And so, when I started meditating and putting down reasons to do it and reasons not to do it, it became quite clear that the option and the invitation were outweighing everything else and that I had to go ahead with him. So I notified him that I was in. And we did it.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, this was after you had been to North Vietnam.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Right. This was May of ’68, and I had been in Hanoi in late January, early February of that year.

AMY GOODMAN: With historian Howard Zinn.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Freeing prisoners of war?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yes, we brought home three flyers who had been captured and imprisoned. It was a kind of gesture of peace in the midst of the war by the Vietnamese, during the so-called Tet holiday, which was traditionally a time of reunion of families, and so they wanted these flyers to be reunited with their families.

AMY GOODMAN: In Catonsville, was this the first time you were breaking the laws of the United States?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: No, I had been at the Pentagon in ’67 in—I think it was in October. And a great number of us were arrested after a warning from McNamara to disperse. And we spent a couple of weeks in jail. It was rather rough. And we did a fast. And we were in the D.C. jail, which was a very mixed lot. So I had had a little bit of a taste during that prior year.

AMY GOODMAN: You and your brother, Phil Berrigan, had an unusual relationship with Secretary of Defense McNamara. You actually talked to him, wrote to him, met him?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yes. I met him at a social evening with the Kennedys in about '65 and after this very posh dinner, which was welcoming me home from Latin America. One of the Kennedys announced that they would love to have a discussion between the secretary of war and myself in front of everybody, which we did start. And they asked me to initiate the thing, and I said to the secretary something about, “Since you didn't stop the war this morning, I wonder if you’d do it this evening.” So he looked kind of past my left ear and said, “Well, I’ll just say this to Father Berrigan and everybody: Vietnam is like Mississippi. If they won’t obey the law, you send the troops in.” And he stopped. And the next morning, when I returned to New York City, I said to a secretary at a magazine we were publishing—I said, “Would you please take this down in shorthand? Because in two weeks I won’t believe that I heard what I heard. The secretary said, in response to my request to stop the war, quote, 'Vietnam is like Mississippi: If they won't obey the law, you send the troops in.’” And this was supposed to be the brightest of the bright, one of the whiz kids, respected by all in the Cabinet, etc., etc., etc. And he talks like a sheriff out of Selma, Alabama. Whose law? Won’t obey whose law? Well, that was the level at which the war was being fought.

AMY GOODMAN: So you went to Catonsville, you went into the draft office.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: We hear about draft card burnings. But this was draft file burnings.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Files.

AMY GOODMAN: You went in with a group of people. Now, some of them—you talked about having been in exile in Latin America, and some of them were there more about treatment of what was going on, the U.S. government, in places like Guatemala than Vietnam, is that right?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: Why were you exiled to Latin America?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Well, there was a lot of controversy and a very hot scene here in New York City, beginning about '67 into ’68. And I think the occasion of my being kicked out was the immolation of a young Catholic Worker in the city here, named Roger LaPorte. He went to the U.N. and burned himself. And, of course, the young Catholic Worker community was devastated by this terrifying event. And they wanted to hold a memorial service, and I was invited to officiate. And in the course of it, I cast doubt upon the judgment of the cardinal that this had been suicide. I said, “I don't think we know. I think this could have been some kind of misguided heroism that said, ’I’m going to give my life rather than take life.'” And that word, of course, got out, and there was panic. There was panic, in the authorities of the Archdiocese of New York and in my order. And they said we've got to—he’s got to—”He’s become a very hot item. We’ve got to get him out of town.”

AMY GOODMAN: Where were you exiled to?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Well, it was a one-way ticket to Latin America. And so, I was down there, I think about five months. And I was in at least 10 countries purportedly reporting back to my editorial people in New York about conditions down there. It was a wrong move. It generated huge publicity not just in the Catholic community but across the country. And they were forced to call me back. So I came back with a stipulation that I go on with my peace work. And they said, “OK, OK.”

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you certainly did in force. And from Catonsville, you served how many years in prison for that?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Well, I think it was about two years.

AMY GOODMAN: And then, with your brother Phil, you founded the Plowshares Movement, your first action in 1980?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: ’80.

AMY GOODMAN: King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.

FATHER DANIEL BERRIGAN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what you did at the GE plant.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Well, we had had meetings, I recall, all that spring and autumn with people about the production of an entirely new weapon, the Mark 12A, which was really only useful if it initiated a nuclear war. It was a first-strike nuclear weapon and was being fabricated in this anonymous plant, huge, huge factory in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. And there had never been an attempt in the history of the antinuclear movement—there had never been an attempt to interfere with the production of a new weapon. And with the help of Daniel Ellsberg and other experts, we were able to understand that this was not a Hiroshima-type bomb. It was something totally different. It was opening a new chapter in this chamber of horrors. So, we decided we will go in there in September of ’70 [sic]. And we did.

AMY GOODMAN: September of ’80?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: ’80. Excuse me.

AMY GOODMAN: And what does that mean, you did?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Well, we didn’t know exactly where in that huge factory these weapons were concealed, but we had to trust in providence that we would come upon the weaponry, which we did in short order. We went in with the workers at the changing of the shift and found there was really no security worth talking about, a very easy entrance. In about three minutes, we were looking at doomsday. The weapon was before us. It was an unarmed warhead about to be shipped to Amarillo, Texas, for its payload. So it was a harmless weapon as of that moment. And we cracked the weapon. It was very fragile. It was made to withstand the heat of re-entry into the atmosphere from outer space, so it was like eggshell, really. And we had taken as our model the great statement of Isaiah 2: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares.” So we did it, poured our blood around it and stood in a circle, I think, reciting the Lord’s Prayer until Armageddon arrived, as we expected.

AMY GOODMAN: And you were tried?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: We were tried and convicted in short order and sentenced, eventually, to three to 10 years. And we were out on appeal for 10 years. The trial was such a farce that the state of Pennsylvania really didn’t know what to do with it. And it went on and on and on. And finally, in 1990, a retired judge, kind of weary of the whole game, gave us both time served.

AMY GOODMAN: Didn’t De Antonio, the filmmaker, make a film about this trial?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And you played yourselves?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yes. And Martin Sheen played the judge. Philip and I told him at the time he was not very good at it. He was not wicked enough.

AMY GOODMAN: Your brother played the judge?

DANIEL BERRIGAN: No. Martin sheen.

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, Martin Sheen played the judge. Phil played himself.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And that launched a movement that continues to this day, where people go to weapons plants and pour their blood and hammer.

DANIEL BERRIGAN: Yes. The latest, strangely enough, is a group in Dublin who three years ago went into Shannon airport and poured their blood, and did symbolic damage to an American troop plane that was secretly refueling at Shannon on its way to Iraq. So they’re being tried for the third time in July of 2006.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Father Dan, we are — we have come to the end of the show, but we’re going to ask you to stay and we’re going to record part two after this broadcast and bring it to our listeners and viewers around the country. Father Dan Berrigan has turned 85 years old, and there’s going to be a large celebration for him this weekend in New York. It’s at the Saint Ignatius Loyola Church at Park and 83rd street Saturday night at 7:00 p.m. We’ll link to the event at our website.

Media Options