Topics

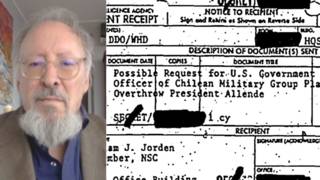

Today is the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination of Chilean diplomat Orlando Letelier and his U.S. colleague, Ronni Moffitt in a car bomb on the streets of Washington DC. The assassination was eventually traced back to the regime of General Augusto Pinochet, which was in the midst of a U.S.-backed campaign against Chilean activists. We speak with Orlando Letelier’s son, Francisco, as well as Peter Kornbluh, author of “The Pinochet File.” [includes rush transcript]

Today is the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt in Washington DC. Letelier was a high-ranking government official in Chile under President Salvador Allende. Following the 1973 US-backed coup in Chile led by General Augusto Pinochet, Letelier was imprisoned and tortured. After his release, he moved to the United States where we worked for the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington.

On September 21st, 1976, Letelier was killed, along with his American colleague Ronni Moffitt, when a bomb planted under his car exploded as they rode into work. The assassination was eventually traced back to Pinochet’s regime which was in the midst of a US-backed campaign against Chilean activists.

On this thirtieth anniversary of his killing, we speak with Orlando Letelier’s son, Francisco Letelier as well as Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at The National Security Archive.

- Francisco Letelier, his father, Orlando Letelier, was assassinated with U.S. activist Ronni Moffitt, in a car bombing Sept. 21, 1976, on Washington DC’s Embassy Row.

Additional information at: Freethefive.org - Peter Kornbluh, senior analyst at The National Security Archive, a public-interest documentation center in Washington. He is the author of “The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability.”

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: Chilean President Michelle Bachelet spoke about Letelier’s killing in her speech to the General Assembly. When President Chavez took the stage not long after her, he also spoke about Letelier.

PRESIDENT HUGO CHAVEZ: President Michelle Bachelet reminded us just a moment ago, the horrendous assassination of the former foreign minister, Orlando Letelier. And I would just add one thing: those who perpetrated this crime are free. And that other event, where an American citizen also died, were Americans themselves. They were CIA killers, terrorists. And we must recall in this room that in just a few days, there will be another anniversary. 30 years will have passed from this other horrendous terrorist attack on the Cuban plane, where 73 innocents died, a Cubana Aviacion airliner.

And where is the biggest terrorist of this continent who took the responsibility for blowing up the plane? He spent a few years in jail in Venezuela. Thanks to CIA and then-government officials, he was allowed to escape, and he lives here in this country protected by the government. And he was convicted. He has confessed to his crime. But the U.S. government has double standards. It protects terrorism when it wants to. And this is to say that Venezuela is fully committed to combating terrorism and violence, and we are one of the peoples who are fighting for peace. Luis Posada Carriles is the name of that terrorist who is protected here.

AMY GOODMAN: President Chavez, speaking at the United Nations before the General Assembly. Peter Kornbluh joins us now in our firehouse studio, senior analyst at the National Security Archive, author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability. We welcome you to Democracy Now!

PETER KORNBLUH: It’s great to be here in the studio with you.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s good to have you with us. We usually either talk to you on the phone or have you in Washington.

PETER KORNBLUH: That is true.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s talk about what Chavez referred to. He talked about Luis Carriles —

PETER KORNBLUH: Luis Posada Carriles.

AMY GOODMAN: — and he talked about Orlando Letelier. Can you talk about the connection?

PETER KORNBLUH: Well, there’s a loose connection. Anti-Castro Cubans that were part of an umbrella terrorist group, according to the FBI, were involved working with the Chilean secret police to assassinate the former foreign minister and former ambassador to Washington, Orlando Letelier, and his American colleague, Ronni Karpen Moffitt, 30 years ago this morning. And those same anti-Castro Cubans were part of a group that planned a series of terrorist attacks across Latin America in the summer of 1976, culminating in the infamous bombing of the Cubana Flight 455 on October 6. And that’s where largely the connection lies. Posada himself was a mastermind of this attack, according to — the plane attack, according to declassified documents.

AMY GOODMAN: You say “infamous,” but I think in this country most people don’t even know what you’re talking about. Explain exactly what happened.

PETER KORNBLUH: The Letelier case?

AMY GOODMAN: No, the Cubana bombing. And then we’ll go — and also after break, I’ll let people know that we’re going to be joined by Orlando Letelier’s son, Francisco Letelier.

PETER KORNBLUH: It is absolutely true that people have forgotten that the most extraordinary act of international terrorism in the western hemisphere, at the time of 1976, was a civilian airliner blown up in midair off the coast of Barbados by bombs planted by anti-Castro Cuban terrorists. This has been largely forgotten, but 73 innocent people were killed, many of them young people — the Cuban Olympic fencing team, six teenaged Guyanese students who were off to Cuba to study medicine on scholarships. Just a horrific act of international terrorism that in the end, in some ways, has gone fully uninvestigated and without really due process in this country.

One of the masterminds lives freely in Miami, Orlando Bosch. He has all but admitted that he planned this bombing of this plane. And the other one, Luis Posada Carriles, is currently in a detention center in El Paso, but could actually be released this week, because the Bush administration has refused to certify him as the terrorist that he is.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And of course, Venezuela has a direct connection to that bombing.

PETER KORNBLUH: Yes, because it was planned in Venezuela. Luis Posada Carriles was a former CIA kind of transfer to the Venezuelan secret police, and he was working out of Caracas with a group of other anti-Castro Cubans who were also part of the Venezuelan secret police planning attacks against Cuba in the 1970s. So Venezuela — he was imprisoned in Venezuela. He escaped in 1985, went to work for Oliver North in Central America in the Contra War and has been in a detention center for a number of months now, but could be freed, because the Bush administration refuses to release the evidence and certify his terrorist past.

AMY GOODMAN: And he would be allowed to walk in the United States?

PETER KORNBLUH: He would join Orlando Bosch freely in Miami. And we’d be faced — the country that purportedly is the leader in the fight against international terrorism would have the two — would be essentially harboring two people who our own intelligence records say are the principal suspects in the bombing of this plane on October 6, 1976.

AMY GOODMAN: Peter Kornbluh, we’re going to go to break. And when we come back, we ask you to stay with us, and we’ll be joined by Orlando Letelier’s son, Francisco Letelier. 30 years ago today, his father, the Chilean diplomat, was killed in the streets of Washington, D.C., along with the American researcher, Ronni Moffitt. We’ll talk about it. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Peter Kornbluh is our guest here in our New York studio, author of The Pinochet File. We’re also joined in Washington, D.C. by Orlando Letelier’s son, Francisco Letelier. Orlando Letelier was assassinated with U.S. activist and researcher, Ronni Moffitt, in a car bombing September 21, 1976 in Washington, D.C.'s Embassy Row. Letelier was Chile's foreign ambassador in Salvador Allende’s government. Salvador Allende, who died in the palace September 11, 1973, as the Pinochet forces rose to power. We welcome you, as well, Francisco Letelier, to this broadcast.

FRANCISCO LETELIER: Thanks, Amy. It’s great to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about this day in 1976? Where were you?

FRANCISCO LETELIER: I had gone that morning to school. I was 17 years old. I was in high school in Bethesda, Maryland. And into my first period class, somebody ran to the classroom I was in, and I was asked to come down to the office, down in the high school office, Walt Whitman High School in Bethesda. I found my brother, Juan Pablo, and my Aunt Cecilia. My aunt told us that there had been an accident, and she had been instructed to take us to George Washington Hospital, close by here to the studio we’re in.

As we drove downtown from Bethesda, we encountered a lot of traffic and a traffic jam as we approached the section of Massachusetts Avenue that’s known as Embassy Row. We kind of detoured, but in the distance I was able to see that at Sheridan Circle there had been an accident. There were emergency vehicles, and there were firemen hosing down the street.

When we arrived at the hospital, my mother was there to greet us. And it was then that we understood that the accident had been a bombing that had taken my father’s life, and what I had seen in Sheridan Circle were the police and the firemen cleaning up the human and automobile wreckage from the bomb blast that took the life of my father, as well as a heroic colleague of my father, a young American woman, Ronni Karpen Moffitt.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Can you tell us a little bit about your father, his involvement in the Chilean democracy movement, the man that you knew, because there’s been very little about — certainly for American viewers — about who was this diplomat who was assassinated on the streets of Washington, D.C.?

FRANCISCO LETELIER: Yeah. My father is remembered for the events that occurred in the last years of his life before he was killed. However, my father was not a politician, and he became a diplomat for the Allende government in the last years of his life. My father actually worked almost across the street from here for ten years, from 1960 to 1970, at the Inter-American Development Bank.

We left Chile shortly after I was born in 1959, the root cause being that my father had supported Salvador Allende’s first bid for the presidency in 1958. In that election in Chile, a conservative candidate, Alessandri, won the election. My father was an expert in copper, and he worked for the National Copper Corporation. When Alessandri came into power, my father was informed that he had lost his job and he would not find work in Chile. So we started our exile. A couple of months after I was born, we moved to Venezuela, where the idea of the Inter-American Development Bank, an international money lending organization that would help in the supposed development of Latin America, was born, with Felipe Herrera, a Chilean economist, and we transferred here to Washington, D.C., which is one of my hometowns where I grew up.

My father, as we grew up with him, was known as an incredibly hard-working and gregarious person. In an interview I read recently, where he was interviewed by a Chilean magazine, Paloma, in 1973, during the brief time that we had returned to Chile and he served as the minister of foreign relations and the minister of defense in the weeks before the coup, he was asked by a journalist, ’What would you have done if your friend, Salvador Allende, had not won the last election or if your life had turned out differently?” And my father said, “I think I would have been a singer.” My father had a beautiful voice. I grew up in a home in which love — the love of art and the love of music was apparent and present in all moments. My greatest memories of my father are when him and my mother would play the guitar together and sing together in our home at the social gatherings we had. He had an enormous library. He loved books. He loved art. He loved music.

And most of all, in his work here in Washington for the Inter-American Development Bank, he had a very clear vision of a united Americas. He made no differentiation between north and south. He really had a Bolivarian pan-American vision of these continents. And he was extremely, extremely obsessed and interested in issues of development and how to channel resources to the places in our world, in our nation of the Americas, how to channel those resources to the places that needed them the most and to bring social justice to the corners where it didn’t exist.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Peter Kornbluh, you have been doggedly pursuing the documentary evidence of who was involved and how this assassination occurred. Could you talk about that, what you’ve uncovered?

PETER KORNBLUH: Let me just say, listening to Francisco Letelier talk about Orlando, that Orlando Letelier was just an extraordinary human being and has been a tremendous loss to all of us and to the community that we’re all a part of in the international community, not having him here for the last 30 years, as well as our loss of Ronni Karpen Moffitt, his colleague at the Institute for Policy Studies, who was a 25-year-old woman from New Jersey and just had a full life of progressive work in front of her. And we truly miss them.

But, you know, we have been working for years to get the declassified record on the Letelier assassination out into the hands of the family, the Letelier family, into the hands of Ronni’s parents, and into the public domain, really for one reason: because the ultimate person responsible has not been brought to justice, and that is Augusto Pinochet himself. It is clear that the Chilean secret police did not act without his authorization. And certainly they did not come to the streets of the capital city of the United States of America to commit an act of state-sponsored terrorism without the authorization of Augusto Pinochet. But he was not prosecuted by the Justice Department in the late 1970s, when the other Chilean secret police officials were indicted.

And six years ago, the Clinton administration, in part due to pressure from the Letelier and Moffitt families, did reopen the investigation into his role. There was a series of documents we asked the Clinton administration to declassify, identifying Pinochet’s role in the crime and particularly in the cover-up of the crime. And those documents were supposed to be declassified, but they were all diverted into a Justice Department investigation that was going on in the spring of 2000. The FBI was sent to Chile, spent a month in Chile, interviewed 42 people, brought back 42 depositions. There was a report written by the FBI’s international crime division, recommending that Augusto Pinochet be indicted as the mastermind intellectual author of this heinous act of international terrorism.

And instead of his being indicted, the Bush administration just basically sat on this report and continues to sit on this report and, even worse, all of the documents that were withheld as evidence for this investigation. Six years have gone by. We either need an indictment in court of Augusto Pinochet or we need the indictment of history that these secret documents would give us if they were now declassified. And that’s what we’re pushing for today. We really cannot stop in this case until all the historical record has been released.

AMY GOODMAN: Francisco Letelier, what are you calling for now? What would it mean to you?

FRANCISCO LETELIER: The declassification of the documents is essential. It’s essential not only for, as Peter says, historical purposes and the case here in the United States, but it’s also very important for legal efforts occurring now in Santiago. An enormous issue that’s raised in this case is the idea of impunity, impunity by people who are entrenched in power and who hide behind the scenes.

Pinochet and the other individuals that worked to murder my father had already joined in to Operation Condor, which was occurring throughout Latin America and the United States. My father’s murder, Ronni’s murder, was part of Operation Condor. Hopefully the investigation of Pinochet, others that knew about the crime, and the declassified documents will shed further light on Operation Condor, a plan to silence opponents, liquidate opponents, wherever they may be, without respect to national boundaries, working with the intelligence agencies of not only Latin America, but other groups within the United States.

And it’s these other people that were involved in the planning and execution of my father’s murder, as you spoke about earlier — Posada Carriles, being the godfather of many of the men that were involved in my father’s murder. As you know, Guillermo Novo, one of the men that was imprisoned with Posada Carriles in Panama, was released with Posada Carriles. Guillermo Novo actually was flown on a United States plane and brought back to Miami, where he received a hero’s welcome.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s talk for one moment about that, Peter Kornbluh. The timing of that, coming home to Miami, coming out of Panama, and the Bush administration.

PETER KORNBLUH: Well, Luis Posada Carriles and three other anti-Castro Cubans were caught in Panama with 35 pounds of C-4 explosive. They apparently had planned to blow up an auditorium that Fidel Castro was going to be speaking in that would have killed many, many innocent people. And they were finally prosecuted and sentenced to eight years for — not for an assassination attempt, but for a threat to public security. After four years, they were actually pardoned by the outgoing Panamanian president, a conservative. There is some allegation that wealthy Cubans in Miami paid off the president and his people to issue this pardon. Posada became a fugitive. Then Guillermo Novo and two others flew back to Miami. There was a group of anti-Castro Cubans waiting at the airport applauding him. Guillermo Novo was intricately involved in the assassination of Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt. He actually served two years in prison for perjury in that case.

AMY GOODMAN: And wasn’t this the point right before the Republican Convention of 2000, and President Bush — then not president — went down to Miami?

PETER KORNBLUH: President Bush was present, because this was in 2004 —

AMY GOODMAN: 2004, before the second election.

PETER KORNBLUH: — that they came back. But certainly the Bush administration had the opportunity to treat them as terrorists. They had been convicted in Panama of an attempted assassination using C-4 explosives. And instead they were welcomed back to the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: Peter Kornbluh and Francisco Letelier, I want to thank you both very much for being with us.

Media Options