Topics

Guests

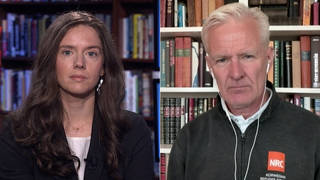

- Alan Snitowco-director of Thirst, the award-winning 2004 PBS documentary on water privatization in Bolivia, India and the United States. He is also a board member of Food and Water Watch and co-author of Thirst: Fighting the Corporate Theft of Our Water.

We end with a major victory for the opponents of water privatization. In 2003, the City Council of Stockton, California, ignored overwhelming public opposition to approve a $600 million, 20-year water privatization agreement. The deal gave a multinational consortium full control over the city’s water, sewage and stormwater systems. But two weeks ago, the council reversed the position and voted unanimously to resume control of its water utilities. We speak with Alan Snitow, co-director of an award-winning PBS documentary on water privatization and co-author of “Thirst: Fighting the Corporate Theft of our Water.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We end today’s show with a major victory for the opponents of water privatization. I’m talking about Stockton, California, a place that’s long been at the center of California’s water wars.

In late 2003, despite concerted efforts by a wide coalition of groups, the Stockton City Council voted in favor of a $600 million, 20-year water privatization agreement. The deal gave a multinational consortium, made up of the Colorado-based OMI and the London-based Thames Water, full control over Stockton’s water, sewage and stormwater systems.

Well, two weeks ago, the city of Stockton reversed its earlier position and voted unanimously to undo the privatization deal and resume control of its water utilities. Before we go to the current victory, let’s go back in time to the Stockton City Council vote in favor of privatization in February of 2003. I want to play a clip from the PBS documentary Thirst that brought national attention to the struggle in Stockton.

DON EVANS: To safeguard the water of Stockton, you have the absolute commitment of our company and you have the commitment of Thames Water to deliver this contract effectively. That’s also, as the president, my personal commitment to you.

STOCKTON RESIDENT: It is clear that the decision to privatize has been made covertly without a public vote.

STOCKTON RESIDENT: I don’t think the people at home realize how many hundreds of people were here and that it’s all filled up back here and downstairs, and that it was hard to hear, so I appreciate [inaudible].

DEZARAYE BAGALAYOS: City Council members, by signing this contract without the vote of the people, you will be betraying the people you supposedly represent. Water is life. This company, OMI-Thames, wants to profit from our water. Water for life, not for profit.

STOCKTON RESIDENT: I’m ashamed that we’ve followed this path and have gone down the road at making something happen that was not consensus building, not citizen-involved. It was basically handed down as a dictate. This is not the principle of an All-America City.

MAYOR PODESTO: OK, Council Member Giovanetti.

COUNCIL MEMBER GIOVANETTI: Thank you. I’m prepared to approve this contract tonight, ahead of the so-called vote of the people.

COUNCIL MEMBER: There comes a time when the people become so involved in an issue that it is important that they be heard by way of the ballot.

COUNCIL MEMBER NOMURA: As a Christian, I’ve always felt that prayer is very powerful. And when this process began, I’ve always prayed for guidance in what I should do. It says that in the Constitution, that you will elect representatives to vote and to make decisions that are best for you.

COUNCIL MEMBER MARTIN: We’ve not been elected to babysit and maintain the city until a vote can be taken by the citizens on major issues.

COUNCIL MEMBER: I do not feel they are too dumb to understand.

COUNCIL MEMBER MARTIN: Nobody said that.

COUNCIL MEMBER: And, you know, the people who founded this republic obviously didn’t think the people were too dumb to run it.

COUNCIL MEMBER MARTIN: Neither Lorrie and I or anyone on this council believes that the people are too dumb to resolve or to understand the issue. That’s not — that’s not what we’ve said.

MAYOR PODESTO: Alright, quiet down. Officers, close the door, please. Tonight I want to thank the council for their indulgence and their endurance and their hard work to come up with whatever their answers are tonight. Do I believe that this should go to a vote of the people? Absolutely not. And that’s for no more reason than I can think any government by initiative is good. There’s been a motion and a second. I’m calling for the question. Please cast your votes. Carries four-three. Thank you all for your hard work.

AMY GOODMAN: With that, in 2003, the Stockton City Council voted for the privatization of their water supply. This, an excerpt of the award-winning PBS documentary Thirst, on water privatization in Bolivia, India and the United States. Alan Snitow is its co-director, also a board member of Food and Water Watch, and recently co-wrote the book that delves deeper into the implications of water privatization in the United States. It’s called Thirst: Fighting the Corporate Theft of Our Water. Alan Snitow joins us from San Francisco. Welcome, Alan, to Democracy Now!

ALAN SNITOW: Thanks, Amy. Thanks for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what happened since 2003 in Stockton, California.

ALAN SNITOW: Well, what’s happened in Stockton is really quite an extraordinary victory and transformation. It proves that privatization is really fundamentally flawed as a model for something like an essential service like water.

What we’ve seen in the past four years, since the private consortium took over, have been spills — sewage spills, with a failure to inform people at the height of the summer when the river was being — when people were using it for recreation and swimming. There was a pass of who was going to tell people that the water actually had fecal matter in it. You’re talking about a series of problems, in which you brought in a lot of temp workers, non-union contractors. There were spills into irrigation ditches. There were fines. There was lack of transparency. People couldn’t find out what was going on. The rates went up.

There’s a series of problems, one after the other, so that in the end you got not only unanimous city council reversal of its decision four years earlier, but even the mayor who had been pushing this in the past, the former mayor, said he agreed with the council decision. The city newspaper, the Stockton Record, which had been a supporter of privatization, said they supported the council decision. There was no one willing to go to bat for this consortium, OMI-Thames, and the only reason that people are not really getting down on them in public is that they signed a no disparagement agreement.

This is the way things work when you make a contract with a private company for something that’s really an essential service that people have a right to have. You know, this is something that is too key. It is really — you know, they say that police and fire and schools have to be something that’s in the public sector, that’s run for the people. Well, you know, there’s something else that also has to go in there, and water — and some of us would also say, I suppose, healthcare.

AMY GOODMAN: But how did Stockton get out of it? It was a 20-year deal. And how did this consortium approach Stockton?

ALAN SNITOW: You know, when people say that there’s a contract — “Oh, it’s a safe thing to do a privatization, because you have a contract that’s hard and fast” — contracts are changed. That’s what lawyers are for. And when you have certain kinds of noncompliance, when the company is not making money, it’s always possible to say, “Hey, look, guys, you guys are not doing a good job here, and you’re not even making that much money. Let’s make a deal to cut you out and get rid of you and return it to public control.” So that’s what’s happened in this particular case.

And the reason why the company would let it go was that they were not even making money. They realized they were not fulfilling their obligations. But they’re going to take an enormous hit, because Stockton was the largest privatization in the western half of the United States. After Atlanta’s failure by Suez in the 2002, when they were kicked out of Atlanta, you now got another major failure. This is a real blow to the idea that a private company, a contractor, can come in and take over your water supply and do a better job than public employees.

AMY GOODMAN: In your book and also in your documentary — in your book, Alan, Nestle — you talk about Wisconsin, you talk about Michigan. You’re speaking to us from San Francisco, where the mayor has banned the flow of money to buy bottled water. Talk about these local initiatives and where you see them going right now. I think, for most people, this is way below the radar screen. They think of bottled water, one thing, as healthy, and people don’t realize that water supplies are being taken over.

ALAN SNITOW: Well, you know, people have a visceral response to the loss of control of their water. But water is a local issue. So when you hear about Stockton, it’s pretty unusual that you’d hear about Stockton in New York or Michigan or Florida. And the same is true that a small local battle in Massachusetts or in Wisconsin rarely is going to get national press. And the result is that water is a watershed issue. It’s both essential, but it’s also something that you’re not going to hear about outside of the local area.

So what we’ve found is that all over the country, in towns and cities, you’re getting these local movements, visceral upsurges of community reaction to the loss of control of their water services or their water supplies. And supplies — I know that the folks from Corporate Accountability and Michael Blanding were all talking about the bottled water — they’re also having the same kind of reaction of loss of control of their utility. And this has brought now a kind of emerging movement to try to make it not only that bottled water is something that we’re not focusing on, that we’re not going to be drinking, but also that we’re going to actually provide the money that is necessary to make public water universal, affordable and clean.

And to do that, because you have hundred-year-old pipes in the ground, there needs to be federal investment. And the Bush administration has cut back investment in water by billions of dollars every year. And there’s now a fight that’s going on in Washington to create a federal trust fund for water, the way we have for highways or building airports, so that you actually can have a clean water trust fund that makes it possible for local areas, for states and cities, to be able to upgrade their water systems so that they won’t have to have this kind of situation in which the bottled water companies are implying that their water is pure, when actually they’re getting the same source of water, they’re using tap water themselves.

AMY GOODMAN: Back on the issue of Stockton, I mean, didn’t — we’re talking about the state weighing in here, too, a judge saying that the Stockton City Council actually violated the Environmental Protection Act — the state won — by not doing an environmental assessment. And you had the former mayor, Podesto, or the former head of the city council, who voted for the privatization, turning around. How does that all take place?

ALAN SNITOW: Well, when they passed the privatization, they were in a real rush to do it, because the Citizens Coalition, this amazing and tenacious citizens group in Stockton, had gotten 18,000 signatures from people in the city to put a referendum on the ballot to require a public vote for the privatization. The city council voted to approve the privatization just 13 days before that vote was to take place. And in order to do that, they had to put in a line saying, “We are exempting this decision from the California Environmental Quality Act.” That was patently illegal. And the result was that two judges have ruled against the privatization and said to the city that they have to reverse it.

The city had a choice that they could have appealed it; they decided not to. They had a choice to take it to the referendum vote and revote on the issue; they decided not to. So what was really going on here was that the privatization hadn’t worked on the ground, to some extent. It hadn’t worked for the river, it hasn’t worked for the water. And so, they decided unanimously to reverse it.

And one of the things that happens is happening here and around the country, this question about preempting the vote in the referendum. One of the things that we found in the movie and in our book Thirst was that you have a constant drumbeat by these companies to undermine democratic input in order to be able to take control of water supplies, because people want it to be a public service.

AMY GOODMAN: Alan Snitow, we only have a few minutes, so I want to just — bullet points on these struggles that you’ve documented around the country. For example, Nestle comes to Wisconsin Dells in Wisconsin; what happened?

ALAN SNITOW: There, a series of groups got together and battled against the company and drove Nestle out of the state of Wisconsin, an amazing victory there. But Nestle then moved into the state of Michigan, where the Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation has been fighting against their taking water out of aquifers and streams in Michigan. And they just had a Supreme Court decision in the state of Michigan, which was denying citizens’ groups the right to intervene on certain environmental issues. Again, Nestle trying to intervene against the possibility of people taking a direct role in the future of their water.

AMY GOODMAN: And Nestle, which owns among other water brands, Poland Spring, Arrowhead, Deer Park.

ALAN SNITOW: Ice Mountain. Yeah, Deer Park.

AMY GOODMAN: What about Lee, Massachusetts and Holyoke?

ALAN SNITOW: In Massachusetts, there was a real battle, because there’s a state law that allows cities, if they apply for it, to be able to do single-bidder kinds of contracts on essential services. And in Lee, again, a citizens’ movement, sort of spontaneous from below, fought against Veolia North America, a major French-based company, taking over their water. And they fought it successfully.

In Holyoke, they did not succeed. It was very much a parallel case to Stockton, in which Aquarion took over the water system in the city of Holyoke, Massachusetts, again going around the process.

AMY GOODMAN: Lexington, Kentucky?

ALAN SNITOW: Lexington, Kentucky, there, the citizens’ group lost a vote to take back water that was owned by the American Water Company, a part of a big multinational consortium, one of the hundred largest companies in the world, after a multi-year fight. But now it’s coming back to haunt the city. And the fight is once again on the agenda over the future of the water in Lexington, Kentucky.

AMY GOODMAN: And Atlanta, Georgia?

ALAN SNITOW: Atlanta was one of the biggest scandals. The mayor who brought in the privatization was indicted. There were charges that he went to Paris on an all-expenses-paid trip with his mistress, paid for by the water company, and then signed off on massive increases in money going to the water company in Atlanta. They were thrown out by the current mayor, Shirley Franklin, because there was brown water, because there was constant eruptions.

AMY GOODMAN: Alan, we’re going to have to leave it there.

ALAN SNITOW: All right. Thanks so much.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you very much for being with us, Alan Snitow, co-director of the PBS documentary Thirst, author of Thirst, as well, Fighting the Corporate Theft of our Water.

Media Options