Over 2,000 people gathered at Riverside Church in New York on Friday for the funeral of the legendary drummer, educator and activist Max Roach, who died on August 16 at the age of 83. He was credited with helping to revolutionize the sound of modern jazz and for playing a prominent role in the struggle for black liberation at home and in Africa. We speak with two men who have known Roach for decades: Amiri Baraka and Phil Schaap. [includes rush transript]

Over 2,000 people gathered at Riverside Church in New York on Friday for the funeral of the legendary drummer, educator and activist Max Roach, who died on August 16 at the age of 83.

Maya Angelou, Bill Cosby, Amira Baraka, Sonia Sanchez and others credited Roach with helping to revolutionize the sound of modern jazz and for playing a prominent role in the struggle for black liberation at home and in Africa.

Max Roach was born in North Carolina in 1924, but he grew up in Brooklyn. His musical career began in the local Baptist church, and by the age of 16 he was playing with Duke Ellington. A few years later he helped lay the groundwork for bebop with Charlie Parker’s group. Over the next six decades he would remain at the forefront of creative music playing with such legendary figures as Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Cecil Taylor and Archie Shepp.

But to many Roach might be best remembered for a record he released in 1960 along with his future wife, the vocalist Abbey Lincoln.

The cover of the record showed a photograph of student activists from SNCC participating in a sit-in at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C.

Max Roach titled the record: “We Insist: Freedom Now Suite.” It remains one of the most moving musical pieces to come out of the black liberation movement.

At the time Max Roach told Down Beat magazine, “I will never again play anything that does not have social significance. 'We American jazz musicians of African descent have proved beyond all doubt that we're master musicians of our instruments. Now what we have to do is employ our skill to tell the dramatic story of our people and what we’ve been through.’’

In 1961, Max Roach staged a one-man protest on stage Carnegie Hall during a Miles Davis performance because the concert was a benefit for an organization supportive of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Roach’s outspokenness led him to being blacklisted by some in the music industry but he continued to perform and compose into the 21st century.

Roach would also became a leading jazz educator and was the first jazz musician to win a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

Later in the show we will play excerpts of Bill Cosby and Maya Angelou speaking at Max Roach’s funeral but first we are joined by two guests both of whom have known Roach for decades.

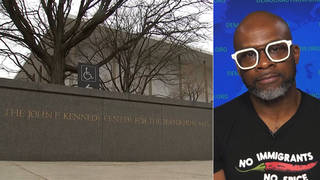

- Amiri Baraka, Max Roach’s biographer and acclaimed poet, playwright, music historian, and activist. In 1992, Baraka worked with Max Roach to compose an opera called “The Life and Life of Bumpy Johnson.”

- Phil Schaap, award-winning jazz historian, radio host, and reissue producer. He is the host of “Bird Flight,” a daily radio program devoted to the music of Charlie Parker. Birdflight is broadcast on WKCR out of Columbia University at 89.9 FM. Schaap also teaches jazz history at the Lincoln Center in New York.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Thousands of people gathered at Riverside Church in New York on Friday for the funeral of the legendary drummer, educator and activist Max Roach. He died on August 16 at the age of eighty-three.

Maya Angelou, Bill Cosby, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez and others credited Roach with helping to revolutionize the sound of modern jazz and for playing a prominent role in the struggle for black liberation at home and in Africa.

Max Roach was born in North Carolina in 1924, but grew up in Brooklyn. His musical career began in a local Baptist church. And by the age sixteen, he was playing with Duke Ellington. A few years later he helped lay the groundwork for bebop with Charlie Parker’s group. Over the next six decades, he would remain at the forefront of creative music playing with such legendary figures as Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Cecil Taylor and Archie Shepp.

But to many, Max Roach might be remembered for a record he released in 1960 along with his future wife, the vocalist Abbey Lincoln. The cover of the record showed a photograph of student activists from SNCC participating in a sit-in at a lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Max Roach titled the record We Insist! Freedom Now Suite. It remains one of the most moving musical pieces to come out of the black liberation movement.

At the time, Max Roach told Down Beat magazine, “I will never again play anything that does not have social significance. We American jazz musicians of African descent have proved beyond all doubt that we are master musicians of our instruments. Now what we have to do is employ our skill to tell the dramatic story of our people and what we’ve been through,” he said.

In 1961, Max Roach staged a one-man protest on stage, Carnegie Hall, during a Miles Davis performance, because the concert was a benefit for an organization supportive of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Roach’s outspokenness led him to being blacklisted by some in the music industry, but he continued to perform and compose into the twenty-first century. Roach would also become a leading jazz educator and was the first jazz musician to win a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

Later in the program, we’ll play excerpts of Bill Cosby and Maya Angelou speaking at Max Roach’s funeral, but first we’re joined by two guests, both of whom have known Max Roach for decades. Amiri Baraka is an acclaimed poet, playwright, music historian and activist. He was the founder of the Black Arts Movement in Harlem in the '60s. In 1992 Amiri Baraka worked with Max Roach to compose an opera called The Life and Life of Bumpy Johnson. Phil Schaap also joins us. He's an award-winning jazz historian, radio host and reissue producer. He’s the host of Bird Flight, a daily radio program devoted to the music of Charlie Parker on WKCR out of Columbia University in New York. Schaap also teaches jazz history at Lincoln Center in New York. Welcome, both, to Democracy Now!

Amiri Baraka, talk about the significance of Max Roach and how you came to meet him.

AMIRI BARAKA: Well, my first cousin, coming back from the Second World War, gave me these bebop records when I was about fourteen, I think it was.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what bebop is?

AMIRI BARAKA: Bebob, well, let’s say that’s the — was the change of the music from the old swing era, you know, in the ’30s, and in the ’40s the musicians sort of reemphasized, you know, improvisation and the blues and the whole percussive underbelly of the music, because the music had become very, very — what would you call it — over-arranged. All of the swing bands began to sound the same. And so, small group of musicians began to create forms that, you know, were sort of lines of demarcation from regular swing music. And Max Roach is one of them.

Plus, Max tried to make the drum a uniquely voiced instrument, independent of the ensemble. He wanted to make a solo instrument. He wanted the drums to be part of the front line, rather than being, you know, hidden in the background. So when I first heard Max was a group called Max Roach and the Bebop Boys, which is God knows how long ago that was.

But it was part of this — what impressed me about what was called bebop, although Max used to complain about the terms “jazz” and “bebop” as being media-created, what impressed me is that, as a kid, it made me think of things that I have never thought before. You know, it was a sort of a freeing of your mind or making your mind actually dwell on things you had never even thought existed.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to play a clip of Max Roach. This was on WABC’s Like It Is. He was interviewed by Gil Noble, who asked him about his mastery of drumming.

MAX ROACH: Well, Gil, this instrument is totally different from any other percussion instrument on the face of the earth. And the technique for dealing with this instrument has added another dimension to the technique of dealing with percussion instruments generally. For example, this instrument, you deal with all four limbs. Most of these percussion instruments in the world that we see, whether they are in Europe, Africa, the Far East, they all play with just their hands. This instrument has added another dimension, and that’s your two feet.

And the basis of that is — I’ll give you an example. You play one thing with your right hand. You call this the swing beat. You play another thing with your base drum. That’s the four-four beat. Then you play another rhythm that’s totally different with your left hand. That’s the shuffle beat. Then with your left foot you play a Charleston beat. Now, in that sense, that’s the essence of this particular drum: you have to learn to deal with all four elements, and they have to blend together, similar to, say, a string quartet. You have to hear everything.

AMY GOODMAN: Max Roach on Gil Noble’s Like It Is on WABC in New York years ago. Phil Schaap, you’re smiling as you’re watching the late Max Roach.

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, it’s a great thing to hear that much jazz information in such a short instance. It’s also amusing to me, because I know who taught Max Roach that: Charlie Parker, at Max’s home, or his mother’s home, in Brooklyn. I guess it’s sixty-two or sixty-three years ago. Max Roach was late for the rehearsal at his own home. And Bird was sitting at the drums, and he said, “Max, can you do this, these four things? And you do them all at the same time, one limb for each event.” And that’s what Charlie Parker could do, and I’m pleased to see that Max Roach learned the lesson. I’m still working on it myself.

AMY GOODMAN: Phil Schaap and Amiri Baraka are with us. We’re spending the hour on Max Roach. Before he was thirty, he was voted the greatest jazz drummer in the world. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re spending the hour on the legendary jazz drummer Max Roach. On Friday, a funeral at the historic Riverside Church was held. Thousands of people came out. Renowned poet Maya Angelou spoke at the funeral for Max Roach.

MAYA ANGELOU: Family, family, family, when great trees fall, rocks on distant hills shudder, lions hunker down in tall grasses, and even elephants lumber after safety. When great trees fall in forests, small things recoil into silence, their senses eroded beyond fear. I have come to sing a song of praise to the courage of black men, in general, black American men, in general, and Max Roach, in particular.

I was the only parent of a young man, a young black man. James Baldwin, John Killens, Julian Mayfield, and Max Roach offered themselves to me as my brother, my brother friends. I was young and quite mad. And so were they. But they were brave enough to be brothers to an African American woman — that’s no small matter — an African American woman who has opinions and is not loathe to tell anybody her opinion at any time, loudly.

Max Roach and the other men I have mentioned dared to say to me things like, “Listen, what you said to your son — he was eleven — what you said to him last week wasn’t all that swift. In fact, that was dumb. You’re raising a black boy in a white country where — poor boy in a country where money is adored, where black is hated, and man — where a man is no small matter. It’s a difference between being an old male born with certain genitalia — you can be an old whatever that is, but to become a man, and an African American man, is no small matter. Help yourself.”

And then, on the other hand, he would call me from New York to California and say, “Girl, I’m so proud of you. I saw you on television. You were brilliant. I’m so proud to be your brother.”

Thanks to Max Roach and African American men, there are some single women who dare to be mothers, dare to be sisters, dare to be lovers, dare to be citizens.

Thanks to Max Roach, all forty years ago, his then-wife Abbey Lincoln, Rosa Guy and I decided we were going to storm United Nations. And we put it to some men. They said, “Don’t be silly.” And we said we’d get the African American — the Harlem community to come down there to United Nations. They said, “Don’t be silly. Those people have never been to Times Square.” Max Roach said, “Do it” — not only “Do it,” “I’ll go with you.” And we went. And Harlem turned up down at United Nations, and we made an international statement. Max Roach.

Max Roach encouraged me to marry a man, a South African freedom fighter who was at United Nations, who was madder than I was. Max Roach said, “He’s good for you. He’ll teach you a thing or two.” He taught me three or four things.

I have wept copiously after losing Max Roach. I also laugh uproariously, because he dared to love me without any sexual innuendos, without any of that, just loved me, told me I was brilliant, much like my own brother. He told me I was brilliant, smarter than most people. He also told me I wasn’t as smart as he was, which was true, which was true.

When great trees fall, it is wise, I think, for us to praise the ground they grew out of.

It is such a wonderful thing to look at his friends and family, to see great names here, great artists, who loved Max Roach, because he had the courage to love us. And so, I’m glad to say we had him. We are bigger and better and stronger, because Max Roach was my brother.

AMY GOODMAN: Maya Angelou remembering Max Roach at Riverside Church on Friday at the funeral of the great jazz legend.

In studio with us, Amiri Baraka and Phil Schaap. Phil, can you talk about the protest that Maya Angelou referred to at the UN, also the Newport Jazz Festival and the one you were at, the Miles Davis concert?

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, the Newport Jazz Festival, the Jazz Artists Guild, the Newport Rebels was the first. It was in July of 1960 and is a continuance of Max Roach’s feelings about the artists controlling, even owning and certainly directing, their own business, which relates initially to his running a record label with Charles Mingus called Debut. This was an expansion of that operation. Now they were going to run their own jazz festival. And they had a lot of musicians on the staff. I was talking with his trombonist Julian Priester on just Friday, and he said, “I was a ticket taker, and so was Mingus.”

And also the Newport festival, the actual Newport festival, was actually closed down by the authorities. There was a lot of — it’s hard to describe it at a distance of forty-seven years, but if you saw West Side Story, there was some youthful rebellion going on parallel to jazz rebellion. But the Max Roach-led festival continued and actually did better business, because they were the only game in town. And when they came back to New York after it, they decided to show that something of substance had happened up there and should be continued.

I remember Jo Jones, the drummer, used to take me to some of these events that they had on a loft. It was around 10th Avenue at West 51st Street, and I even saw some, I guess, previews of the Freedom Now Suite: We Insist! So that was about the Newport Rebels of 1960.

Then, the following year — one of Max Roach’s greatest insights about the contemporary Civil Rights Movement from an American perspective was that it was the same thing internationally, in that he felt that the rebellion against imperialism and apartheid in South Africa and the contemporary Civil Rights Movement here in the United States was one thing, and it’s a blended theme that he puts across brilliantly in his music. And he felt that, well, among other people, the great Miles Davis was too centered on whatever he was doing for the Civil Rights Movement in the States wasn’t even addressing the real issue, which was international. So he decided he was going to make his own rebellion single-handed on stage at Carnegie Hall.

Now, I was ten years old when that concert happened, and my recollections have to be taken with that, you know, information. This is just some kid looking in at — and it’s pretty impressive. A little bit scary, too, you know. I remember, that day, I was becoming closer to a minister who gained Max Roach’s friendship long before I did named Reverend John Garcia Gensel. He really was the counsel for Duke Ellington. And my lasting personal memory of that day was after the concert was over, walking out onto 56th Street and 7th Avenue and seeing Max Roach and Reverend Gensel just casually talking about things. I said, “Well, I bet you those are two very impressive people. I’d like to hear what they’re saying. I’m not sure I’m going to get that close.” And I did, though, eventually.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to break into this discussion of Max Roach to bring our listeners and viewers breaking news. The latest we hear right now, CNN is reporting that Alberto Gonzales, the Attorney General of the United States, has resigned. Now, Amiri Baraka, we brought you here to talk about Max Roach, but your response, the political being that you are, seeing you on Saturday out in Newark marching with a thousand people protesting the war abroad and the war at home.

AMIRI BARAKA: Well, they stalled that long enough. Gonzales had to fall on his sword sooner or later. It was a short sword. It took a long time for him to reach it. But Bush’s whole administration is sort of dying on the vine, you know. I wish it would happen more swiftly than it’s happening. But — I mean, because he’s already violated the Constitution of the United States every kind of way you can think of. I mean, so to continue with this is to just march lockstep toward fascism. One hopes this will, you know, slow it down.

AMY GOODMAN: Charles Schumer, the senator of New York, one of Gonzales’s chief critics, released a statement saying, “It has been a long and difficult struggle, but at last the attorney general has done the right thing and stepped down. For the previous six months, the Justice Department has been virtually nonfunctional, and desperately needs new leadership,” Schumer said. He went on to say, “We beseech the administration to work with us to nominate someone whom Democrats can support and America can be proud of.”

AMIRI BARAKA: I’m just sorry that Gonzales resigned before he could arrest himself. That would be the best arrest we’ve heard, basically, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: The protest that happened in Newark was one of the largest in decades.

AMIRI BARAKA: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Scores of groups joining together with People’s Organization for Progress.

AMIRI BARAKA: Well, you see, what I said then was that we need to join the antiwar movement with the anti-imperialist movement and the anti-racist movement, because people who want to fight against the war without seeing that war has its origins in imperialism, and that has to be countered. You have to start at the root, because otherwise, just by opposing this war, there might be a brief pause, and then there will be a war with Iran, and then there will be a brief pause, and then there will be a war with North Korea, then there will be a brief pause, and then some fool will say we should go to war with China. I mean, so it’s imperialism is at the root of the problem. You know, the war is just a reflection of imperialism, sort of an unbridled attempt to, you know, claim the world.

AMY GOODMAN: There are rumors — just rumors, so far — that President Bush is going to tap Michael Chertoff, the Secretary of Homeland Security, to be the next attorney general.

AMIRI BARAKA: Because he’s done such a good job. I mean, Katrina should, you know — I mean, I don’t have any faith in Chertoff, since he used to be attorney general in New Jersey. You know, I mean, he’s led a long and checkered career, you know? Appointment without, you know, accomplishment is what I see.

AMY GOODMAN: Phil Schaap, how involved was Max Roach in the politics of the day? I mean, we’ve been talking about his deep involvement in linking international with local issues.

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, he would be very, very much involved in your show to sort of — a shortchange that you don’t have him as a guest this morning to comment on these very same events. I was sort of looking forward to the impeachment also. Maybe he could have emulated some of his predecessors, like John Mitchell and Gaston B. Means — Gonzales, of course, I’m speaking about, not Max Roach.

But you can hear in Amiri’s statement that this bigger picture and the connections is something that is a real story and a real theme and a real concept. Max Roach was about that. He understood these connections. He spoke about them frequently. You know, I used to go over to Roy Eldridge’s house on election night, because I’m from Hollis, Queens. That’s where he lived. And it used to be great to see Roy Eldridge sort of talk about what was happening. And Max would say, “Well, what did Roy say?” because they had both been in this Newport rebellion in 1960, two generations.

AMIRI BARAKA: The '62 thing actually was against the murder of Patrice Lumumba. And that's what brought everybody down there, and the fact that Maya, who, people don’t know, was intensely political back in those days. You know, she’s one of the people — her and Abbey — that climbed up into the United Nations, and they were taking off their shoes, throwing them down there at the Negro bunch, and it was very interesting. And like I said in that thing, some people I’ve met as political activists, you know, who I didn’t even know were poets and musicians at the time.

AMY GOODMAN: Amiri, I wanted to turn to your poem that you read at the funeral of Max Roach on Friday, reading the poem that you wrote for Max Roach’s seventy-fifth birthday called “Digging Max.”

AMIRI BARAKA: I wrote a poem for Max on his seventy-fifth birthday. This is a picture of Max and I in Paris. And this is called “Digging Max.”

(At

Seventy Five, All The Way Live!)

Max is the highest

The outest the

Largest, the greatest

The fastest, the hippest,

The all the way past which

There cannot be

When we say MAX, that’s what

We mean, hip always

Clean. That’s our word

For Artist, Djali, Nzuri Ngoma,

Senor Congero, Leader,

Mwalimu,

Scientist of Sound, Sonic

Designer,

Trappist Definer, Composer,

Revolutionary

Democrat, Bird’s Black Injun

Engine, Brownie’s Other Half,

Abbey’s Djeli-

ya–Graph

Who baked the Western industrial

singing machine

Into temperatures of syncopated

beyondness

Out Sharp Mean

Papa Joe’s Successor

Philly Joe’s Confessor

AT’s mentor, Roy Haynes’

Inventor, Steve McCall’s

Trainer, Ask Buhainia. Jimmy Cobb,

Elvin or Klook

Or even Sunny Murray, when he aint

in a hurry.

Milford is down and Roy Brooks

Is one of his cooks. Tony Williams,

Jack DeJohnette,

Andrew Cyrille can tell you or

youngish Pheeroan

Beaver and Blackwell and my man,

Dennis Charles.

They’ll run it down, ask them the next

time they in town.

Ask any or all of the rhythm’n.

Shadow cd tell you, so could

Shelly Manne, Chico Hamilton.

Rashid knows, Billy Hart. Eddie

Crawford

From Newark has split, but he and

Eddie Gladden could speak on it.

Mtume, if he will. Big Black can

speak. Let Tito Puente run it down,

He and Max been tight since they

were babies in this town.

Frankie Dunlop cd tell you and he

speak a long time.

Pretty Purdy is hip. Max hit with

Duke at Eighteen

He played with Benny Carter when he

first made the scene. Dig the heavy learning that went with

that. Newk knows,

And McCoy. CT would agree. Hey,

ask me or Archie or Michael Carvin

Percy Heath, Jackie Mc are all hip to

the Max Attack.

Barry Harris can tell you. You in

touch with Monk or Bird?

Ask Bud if you see him, You know he

know, even after the cops

Beat him Un Poco Loco. I mean you

can ask Pharaoh or David

Or Dizzy, when he come out of hiding,

its a trick Diz just outta sight.

I heard Con ??Alma and ??Diz ??and ??Max????

????In ??Paris, just the other night.

But ask anybody conscious, who Max_?????

?????Roach be. Miles certainly knew?????

?????And Coltrane too. All the cats who?????

?????know the science of Drum, know?????

?????where our?????

?????Last dispensation come from. That’s?????

?????why we call him, MAX, the ultimate,?????

?????The Furthest Star. The eternal?????

?????internal, the visible invisible, the?????

?????message?????

?????_From afar.

All Hail, MAX, from On to Dignataria__?????_

?????_to Serious and even beyond!_?????

?????_He is the mighty SCARAB_, Roach the_ SCARAB_, immortal as_?????_

?????our music, world without end.?????

?????Great artist Universal Teacher, and?????

?????for any Digger?????

?????One of our deepest friends! Hey MAX!?????

?????_MAX! MAX!

AMY GOODMAN: Poet Amiri Baraka, Max Roach’s biographer and acclaimed playwright, music historian and activist. We are going to go to break. When we come back, we’ll hear Bill Cosby remembering Max Roach.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Max Roach died last week at the age of eighty-three. He died of Alzheimer’s. Bill Cosby also paid tribute to Max Roach at his funeral at Riverside Church. He said, “Why I became a comedian is because of Max Roach. I wanted to be a drummer.” Cosby went on to recall how he spent $75 on a drum set and then tried to imitate his favorite jazz drummers.

BILL COSBY: Art Blakey came to town. And Art Blakey sat down, and I watched. Doo-da-doo be-shok! And I saw him. He hit it twice. Shzook! And he hit it so fast that it came out shzok! I said, “Ah-ha! I got you now, Art Blakey!” And I went home, and I looked at the drum and the sticks, and I said, da-da da-da shzok!, and it came out shzok! on the snare. Got you! Ha ha!

Then bought a LP. Max Roach and sp-da-da-da da da-ba-ba-ba-baa! Da-da-da-da da da-da-da-da daa! Fa-da-da-da-da da-da — and I kept — I kept falling behind. It was ba-da-da-baa tsooee — and then the left hand — the left hand said, “Look, you play, and because” — and the right hand said, “Well, if you play, then I know — I lose,” and said, “Well, just fill boom!, hit the base drum and then try to catch up and, oh, just do something.” And they kept playing — de-ba-da-ba-da da-dwi-bi-di-da, oh-ji-ba-da-bla oollllll blllllll dllllll blllllll bop!

Max Roach came to town. He came to the Showboat. And I sat there. Max came out, had a blue blazer on with some kind of crest. I was with my boys from the projects. And one of my boys said, “Max got a boat.” And the musicians did — da-bleen-din-dol-ding-dol-din-blorp-worp, ha-da-ha-da. And Max sat down, and his face never changed. He took both sticks, and he said, bash, bash, fa-di-di-di-di-di-di-di-di-daa, da-da-da-daa-da-da-da-da-daa, vi-di-di-di-di-di-di-di-di-daa, va-di-di-di-di — and I went home. It was no tricks. Nothing I could take.

When I finally met him in person to the point where Max Roach knew who I was, and he came over to me, he said, “Bill Cosby!” I said, “Let me tell you something. You owe me $75.”

AMY GOODMAN: Bill Cosby at the funeral of Max Roach. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report.

Our guests live in studio, Max Roach’s close friends, Amiri Baraka, who wrote Max Roach’s biography, though it hasn’t been published — we’ll talk about that — and the jazz expert Phil Schaap, very close to Max Roach. Can you talk about how Max Roach changed the role of the drummer, Phil?

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, he’s a continuation of the drummer becoming a leader and certainly taking a solo. That transition is not that easy to perceive now after seventy years, but in the '30s most drummers didn't solo, and they were part of a team, three or four as one, as Monk would put it, the rhythm section. And Max Roach is someone who put the drums down front and center.

But it’s beyond that. It’s also the completeness of his music, the drums as a melodic instrument, the sound — you know, Bill Cosby was talking about sounds, but also pitches. I mean, the idea that the drums themselves could be the entire orchestra, I mean, this is pretty advanced thinking. And Max Roach, of course, had — boom —- an all-percussion ensemble that played tunes, many which, of course, Max Roach wrote, which, of course, is [inaudible] -—

AMY GOODMAN: And playing different tunes with both hands and both feet.

PHIL SCHAAP: All four limbs for all four players. And one of the things about that band was that Max — and this was really just to show the talents of the band — he had them keep switching, so you would play a different instrument on every number. So it was a very difficult band to play in, I imagine, and a very astounding band to hear. It was actually shocking.

AMY GOODMAN: How did he change jazz?

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, he’s, first of all, the drummer for bebop. And bebop is as much a change in jazz as one can imagine, other than its birth through swing. It’s the change of the flow of the rhythm. He’s the drummer who changed that flow. He was the drummer on Charlie Parker’s first records, Miles Davis’s first records, Stan Getz’s first records, Bud Powell’s first records, J.J. Johnson’s first records. He’s the drummer on The Birth of the Cool. He’s the drummer on the first bebop records, period.

And bebop is an important thing. It’s sort of like a language, a root language like Latin. People actually don’t play bebop. We don’t actually speak Latin. What we speak are the languages that are descendent. One of the key ones would be hard bop. Max Roach is as much an innovator to that breakthrough as anybody we could name. And he sort of retooled bebop, making it funkier, and he made it more blues-rooted therefore, forceful, and, most astoundingly, prettier.

AMY GOODMAN: Amiri Baraka, the role of the drum, the significance of the talking drum?

AMIRI BARAKA: Well, see, one thing that Max — and Max was a great historian, too. I mean, when I used to go to his house two, three times a week or a year or so, year and a half, to write his biography, one thing he told me, he said that the whole drum set is an industrial machine. It’s not like hand drums. And so that — and it actually reflects the one-man bands that came off the plantation, where they would put the cymbals and everything on their back and go down and try to make a living playing all those things at once, horns and — you know, so that this industrial instrument — there’s even a movie that was made, a film, made by — jeez, I taught with this guy at Yale — but, anyway, a film where he takes Tony Williams to Africa and sets up the instrument on the shore and plays. And a couple minutes later, from the interior, they answer him — ba-da ba-da — with the hand drum. And they say, “We hear you all.” In other words, they thought it was a lot of people. They say, “We hear you all, but we do not understand what you’re saying,” to show you the difference between, you know, the Afro-American and the Africans, say, “We do not understand what you’re saying.”

But Max had that kind of — that genealogy in what he did. He knew hand drum, you know, and he could sort of reflect that genealogy, I mean, from old-time through swing. You know, his mentor, I guess, was Jo Jones, but also it was a Wilson Driver, who had something to do with that. So he reflected an old tradition, you know.

I did a gig with him and Archie Shepp in Philadelphia one time, and I came there with all my poetry, and he says to me, “No, no, you can’t read anything. You’ve got to do what we do. We’re going to improvise. You have to improvise.” I said, “Oh, my god! This is going to be wild.”

AMY GOODMAN: Sonia Sanchez said the same thing. She also spoke at the funeral, the leading figure in the Black Arts Movement paying tribute to Max Roach on Friday.

SONIA SANCHEZ: I have seen this Maxwell man, this Maxwell Roach man. From the middle of the twentieth century to the beginning of the twenty-first century, I have seen him at work moving in the bloodstream of his people. I have seen him look up when someone inferred that this long voyage of artistry had been futile and had lacked dignity. I have seen his tongue track down these disbelievers. I have seen his mouth silence these diplomats of the dead and anoint our hands with eyes.

He has known for a long time that we stand on an earth collapsing in a pallet of pain, that we stand in the tracks of conquistadores and imperialists, homophobes and racists, terrorists and pornographers, sexists and voyeurs, countries and people who want to own everything that exists, who try to extract our rhythms and put them in the pillbox to be taken once a day, earth studiers, doomsayers, invasive actors, offense to their own blood.

And this Maxwell Roach continued to hold up the air. No mysteries surrounded him. The cities knew him, felt his touch, saw his solitary eye demanding dignity and change, saw his sparkling hand scoop thunder from his pores. And his drums ask, “Who will hold them when they are weary?” And his drums ask, “Who will carry them and remember that they have hearts?”

And you came towards us, Max, hands outstretched, suffering our ignorance and indecision. You came warrior-clear, your intellect kissing our spines, and you brought us life. You came feet, hands, head, heart, strumming sweet life-life-life-life-life-ooooh-life-life-life-life-life, and we were reborn in your spreading sails of flesh.

Brother Max, baba-baba-baba-baba-baba, Brother Max, baba-baba-baba man, whenever I hear a drum exploding in a room, I remember the first time I saw you on stage, your drum crashing against the stars. You let me ride on your riff. You held me tight against this hard earth, and I knew you, man. I knew you would hold us all tight against this hard earth, make our living and dying matter. And you pulled our bodies homeward until we shouted, “Amen! Awomen! Amen-men-men-men! Awomen! Awomen! Awomen! Awomen! Awomen!”

And you played, and your hands kept reaching for God. And you played. And your hands kept reaching for God. And you played, “I want to go home, gots to get home, gots to walk on the water, gots to ride the air, gots to ride the lightning across the sky, gots to cross myself one day and wake up home.” And you did, my dear brother. We heard the prayer in your hands. And you crossed yourself last Thursday morning and woke up home. Indicia. Indicia-a-a. Indi-indicia-a-a, you men phon., close with the ancestor.

AMY GOODMAN: Poet Sonia Sanchez at the funeral of Max Roach. As we wrap up, Amiri Baraka, you wrote Max Roach’s biography with him. Where is it?

AMIRI BARAKA: Well, my copy is in a box. You know, all the — actually, I did that twice. Max was not satisfied with the first writing of it. He said to me — you know, when I showed it to him, he read it, and he asked me — he says, “Amiri, is there another word for M.F.?” And I said, “Well, I don’t know, Max. I have to go think about it, you know.”

But what it was really is that he, seeing himself as he was as a young man, he wasn’t really happy with that. I mean, you know, everybody wants to mature. But he had told me out of his mouth his life, and I had dutifully written it down, but he didn’t want to be that anymore.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I hope to see it published someday.

AMIRI BARAKA: I hope so.

AMY GOODMAN: Amiri Baraka and Phil Schaap, I want to thank you so much for being with us, and being it’s Lester Young’s birthday, I’m glad, because it meant you, Phil, were free from WKCR, but people can listen to your program every morning at wkcr.org.

Media Options