Guests

- Scott HortonNew York attorney specializing in international law and human rights. He is also a legal affairs contributor to Harper’s magazine, where he writes the blog “No Comment.” He has the cover story in the latest issue of the magazine. It’s called “Justice After Bush: Prosecuting an Outlaw Administration.” On Thursday he will speak at 'After Torture: A Harper’s Magazine Forum on Justice in the Post-Bush Era' in New York City.

We speak with Scott Horton, an attorney specializing in international law and human rights. He is also a legal affairs contributor to Harper’s magazine, where he has the cover story in the latest issue, called “Justice After Bush: Prosecuting an Outlaw Administration.” We also speak with Horton about Eric Holder, President-elect Barack Obama’s choice for attorney general. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to continue with Matthew Alexander, who’s written the book How to Break a Terrorist

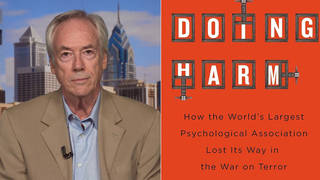

. We’re also joined by Scott Horton, an attorney who specializes in international law and human rights. He’s written extensively about prisoner abuse in Iraq. He’s the legal affairs contributor to Harper’s magazine and writes the blog “No Comment.”

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Scott Horton. As you listened to Matthew Alexander lay out his story, it’s certainly a different approach than we’ve gotten out of many of the interrogations at Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib and other places.

SCOTT HORTON: Well, this is obviously a very important book and an important account for many reasons. I think, one, it really demonstrates the integrity and the effectiveness of traditional American military values and techniques. It shows that they work, and they harvest results. The pinpointing of Zarqawi was certainly one of the two or three most important intelligence breakthroughs in the course of this entire war effort. So that’s, I think, a very, very striking point.

But second, our discussion about torture and the introduction of torture, to date, has really focused on events that happened at Abu Ghraib, things that happened at Guantanamo, a prominent memorandum signed by the Secretary of Defense, Rumsfeld, early on. But I understood instantly, when I heard his account about the pushback he got from the Department of Defense, why. And that’s because his account breaks extremely important new ground. It shows us that there is an entire another channel in which torture developed, and that’s inside of the Special Operations Command.

And by the information I’ve collected, which I think this account confirms, that goes back to the beginning of the conflict, 2002. Special Operations Command set up, operated essentially as a personal fiefdom by Dr. Stephen Cambone, who was the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence. And Dr. Cambone was authorizing taking the gloves off, using brutal methods, using torture. And that happened way before the Justice Department got involved, memoranda were written, everything else.

Now, why is that significant? This timeline is very, very important, because it shows that the use of torture and torture techniques comes much earlier than the crafting of the torture memoranda and the Justice Department, the approval process. And that then shows, in turn, that these memoranda were written after the fact in an effort to protect people who had already engaged and implemented this policy. So this is a bombshell, in fact.

AMY GOODMAN: Matthew Alexander, did you see memoranda? Did you see memos posted about what you could do?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: Yes. I mean, there was some confusion amongst all interrogators, at some point, about what was allowed and not allowed, because at one point, what was allowed in Guantanamo Bay was not allowed in Iraq. And I had interrogators on my team who had come from Guantanamo Bay, and things that they were allowed or not allowed to do there were allowed or not allowed in Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: For example, dogs.

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: Dogs were not allowed. I know they were allowed at one point at Guantanamo Bay. But by the time I arrived in Iraq in early 2006, dogs were definitely outlawed.

But let me give you another example. Good cop, bad cop, which is —- you know, it’s a technique that we use all the time in the criminal investigative world. It’s an effective techniques. But it wasn’t allowed in Iraq for a long time, although it was allowed as an enhanced interrogation technique in Guantanamo Bay. So this -—

AMY GOODMAN: Why wasn’t it allowed in Iraq? Because they didn’t want the good cop?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: You know, I’ve never gotten a good explanation about why we weren’t allowed to use good cop, bad cop. You know, if it’s torture, then why do we use it in criminal interrogations? It’s not. And I think it more has to do with the fact that there wasn’t a uniform policy from the beginning for all interrogators that applied across all theaters, which there should have been.

AMY GOODMAN: Scott Horton, your latest piece in Harper’s magazine, “Justice After Bush: Prosecuting an Outlaw Administration” — you think President Bush on down should be prosecuted?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, I think we have to start with a proper investigation before we reach conclusions about who should be prosecuted and for what crimes. I think there’s simply no question but that serious criminal conduct occurred. And, in fact, we’ve had prosecutions already. I mean, we can count seventeen NCOs, so it’s grunts at the bottom of the military food chain who have been prosecuted for this abuse. There has been no accountability, however, for those who made policy. And I think as a matter of proper administration of criminal justice, it’s the policymakers who should most be held to account.

So the first step is to establish all the facts and establish them carefully and calmly. Who took what decisions when? Security classifications had been wielded very effectively to obscure much of what went on. I think, you know, Matthew’s statements make that clear, and the redactions in his book make that clear. In particular, we know these things were going on inside the Special Operations Command, and security classifications were used to keep that entire tale secret, even secret from congressional oversight committees that attempted to probe into it. So the answer here, I think, is for President-elect Obama to appoint a presidential commission of inquiry, like the Rockefeller Commission, or a hybrid presidential —-

AMY GOODMAN: What’s the Rockefeller Commission?

SCOTT HORTON: The Rockefeller Commission was appointed to look into criminal conduct within the CIA in 1975, the same things that the Church Committee was looking into. Or something like the 9/11 Commission, which is a hybrid congressional-presidential commission, and fill it with eminent persons, give it a clear mandate, and let them get to the bottom of the facts. When the facts are established -— and that’s a process that I’m convinced would take a couple of years —- then we can deal with the question of prosecutions.

AMY GOODMAN: Scott Horton, has any US official ever been prosecuted for torture?

SCOTT HORTON: We’ve had military officers who have been prosecuted for torture twice: in 1903 and in 1968. Both of those cases involved waterboarding. And we had camp commanders during the Korean conflict who were court-martialed and punished for abuse of detainees. So the answer is yes, but higher-level policymakers, no. But senior military officials, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Obama officials, advisers to Obama, have said that he is unlikely to go after anyone involved in authorizing or carrying out interrogations. And then there’s the question of President Bush, whether he would issue any kind of pre-emptive pardons.

SCOTT HORTON: Well, that’s an AP report, and the AP report relies on two sources, and I believe one of those sources is John O. Brennan, who was the chief of staff to Mr. Tenet, who would of course be a target of such an investigation, so it’s easy to understand why he would say Obama won’t do it. I’m told -—

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, he was head — he is head of the transition team on intelligence, but has taken himself out of the running.

SCOTT HORTON: I think that’s correct. And I’m told by the Obama transition team that no decision has been taken on this issue, nor is there any particular rush or need to take a decision before January 20th. In fact, I think there’s an important piece they’re waiting to see play out, and that is whether President Bush is going to issue a pre-emptive class-based pardon. And I think there’s a lot of speculation he’ll do it.

AMY GOODMAN: What does that mean?

SCOTT HORTON: The President, before he leaves office, may very well — and if he does it, I think it will be on his last day, on the way out — issue a pardon to all those who were involved in the formation and implementation of his enhanced interrogation program, what he refers to affectionately as “my program.”

AMY GOODMAN: Now, this is from Reuters. It says that ex-generals will be going to Washington to urge Obama to take action on the torture issue. They’re saying Barack Obama should act, from the moment of his inauguration, to restore US image, battered by allegations of torturing terrorism suspects. They’re planning to press their case with the President-elect’s transition team in Washington, about a dozen retired generals and admirals expected to meet with his team saying that they’re going to offer a list of anti-torture principles, including some that could be implemented immediately. Matthew Alexander, do you know about this?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: I’ve heard of this. And there’s not just retired generals; there’s people within the military who have stood up. There’s people who stood up with me in Iraq and said no to torture and that they wouldn’t do or participate in certain things. Colonel Steve Kleinman, who is probably the most senior officer we have in the military who has been trained as an interrogator, has spoken before Congress several times. And his story is also told in Jane Mayer’s book, The Dark Side, about how he was sent to Iraq to teach interrogators how to use SERE techniques.

AMY GOODMAN: Psychologist — isn’t Kleinman a psychologist?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: SERE techniques are the evasion and resistance techniques that we teach our own troops how to resist against interrogations. And he was sent to Iraq and told to teach interrogators how to use these as torture weapons, and he refused to do so. So the change, I think, has come from people within the military who have stood up and said, “No, this is against American principles.”

AMY GOODMAN: Were you subjected to SERE techniques? I mean, did you go through that training?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: I did go through SERE training. And I remember this moment I’ll never forget at the end of SERE training.

AMY GOODMAN: Where were you?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: I was in Spokane, Washington. It was very cold. It was the first week of February, subzero temperatures. And it’s very challenging training. You know, it’s a prisoner of war environment. And at the end of the training, I remember, we stood in formation, and we were very exhausted, and they played the national anthem. And afterwards, an instructor gave a speech, and he told us about how some American prisoners of war in Korea had been tortured to death and refused to give up information. And I remember taking great pride in the fact that our country did not torture, that we did not resort to such practices. And that’s why I felt such an obligation to write this book and to get the word out that we’ve got to return to that. We’ve got to return to a place where we do not conduct torture in any organization within our government.

AMY GOODMAN: The issue of torture has raged in the association of psychologists, the American Psychological Association, psychologist participation. Did you work with psychologists?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: We had psychologists. They did not advise on the tactics or techniques that we should be using for interrogation. They actually were there for the safety of the detainees, to ensure that if someone — one of the detainees started to experience problems mentally, that we could identify that and get them the appropriate help.

AMY GOODMAN: Who do you believe should be held accountable?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: I can’t make judgments about accountability. I mean, I’m a soldier, and ultimately my job is to fix and make better our processes that help us defend our nation. You know, the accountability finger for torture, I think, you know, it is a leadership issue. I think we set examples from the top down, and our troops follow those. But at the same time, I think all the troops do have training to know what’s right and wrong.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think prosecution of those who crossed the line would help people understand what’s right and wrong?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: I would say that if it was an interrogator who had crossed the line, they certainly would be prosecuted.

AMY GOODMAN: If it was an official?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: If they crossed the line and broke the law, yes, I think they should be held accountable.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think that should go right on up to President Bush?

MATTHEW ALEXANDER: I think it should go to anybody who breaks the law. I don’t think the law — I think the history of the United States has proven, you know, that we impeach and try anybody who breaks the law. It’s not really for me to decide who has broken the law or who hasn’t. What I know is that we’ve got to change the system to do a better job of interrogating.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to ask about Eric Holder, the man President-elect Barack Obama has asked to be Attorney General. If confirmed, he would become the first African American to lead the Justice Department. Holder served as Deputy Attorney General in the Clinton administration and as US attorney for the District of Columbia. He served as an adviser to Obama’s campaign on legal issues and served on his vice-presidential selection team. This is some of what Eric Holder had to say Monday after Obama officially introduced him as his pick for Attorney General.

ERIC HOLDER: I also look forward to working with the men and women of the Department of Justice to revitalize the department’s efforts in those areas where the department has unique capabilities and responsibilities in keeping our people safe and ensuring fairness and in protecting our environment. This president-elect and the team you see before you are prepared to meet the challenges that we will confront. But from my experience at the Department of Justice, I know that we cannot be successful if we act alone.

We must never forget that in many ways those in state and local law enforcement are our first line of detection and protection against those from foreign shores who would do us harm. We will need to interact with our state and local partners in new innovative ways to help them solve the other issues that they confront on a daily basis. National security concerns are not defined only by the challenges created by terrorists abroad, but also by criminals in our midst, whether they be criminals located on the street or in a board room.

AMY GOODMAN: Scott Horton, the pick of Eric Holder as Attorney General and what he’s just said?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, of course, he’s inheriting a Justice Department that is at its all-time low point in public esteem, so he will have an immense job ahead of him. He had a reputation while he worked at the Justice Department as a person who wanted to keep out of politics and keep out of the headlines, do his job, follow the book, follow the rules. I think he was very, very well-regarded by his colleagues at the Justice Department. And — but, of course, he brings a little bit of negative baggage, particularly in connection with the pardon of Marc Rich. I’m sure he’s going to get embarrassing questions about that.

AMY GOODMAN: And Marc Rich was the man that President Clinton pardoned.

SCOTT HORTON: After receiving campaign support from the Rich family.

AMY GOODMAN: And Eric Holder was in charge at the time in vetting the pardons?

SCOTT HORTON: That’s right. And I think it was revealed in the last forty-eight hours that his role was considerably greater than the public knew previously.

Also, in private practice, he was involved with Chiquita Banana and some dealings in Latin America that I think are a little bit unsavory.

AMY GOODMAN: Colombia.

SCOTT HORTON: But — that’s right. But I think, you know, private attorneys don’t always get to pick all their clients. So I think he’ll be forgiven on that.

On these issues relating to torture and Guantanamo, 2002, he was supportive of the administration’s position on establishing Guantanamo, but within two to three years, he turned quite critical of it and gave a speech at the American Constitution Society, which I personally witnessed, in which he spoke in extraordinarily impassioned tones about the deterioration of our legal regime and our respect for the rule of law that Guantanamo had come to represent. So I think he stands exactly where Barack Obama stands on those issues, and I think — I have no doubt about his commitment to shut down Guantanamo and to bring an end to the torture policies. I think he’s really clear on all of that.

AMY GOODMAN: Unlike Barack Obama, Eric Holder is opposed to the death penalty. What influence do you think that would have?

SCOTT HORTON: Well, I think the Attorney General gives recommendations in connection with clemency and pardons, and I think we can see some of that. I think the Bush administration had ratcheted up — had taken an extremely aggressive position on the administration of the death penalty, had stripped away discretion from US attorneys on it. In fact, we have one US attorney in Arizona removed because of his objection to policy positions. I expect to see that reversed now.

AMY GOODMAN: He was also part of the legal team that worked to reauthorize the USA PATRIOT Act.

SCOTT HORTON: That’s correct. And I think that — but I think there he showed, you know, traditional law enforcement community biases for a broader mandate. Eric Holder is, I think, closer to the civil libertarians than any of the Bush attorneys general, but he’s not a civil libertarian by any stretch of the imagination.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you both for being with us. Matthew Alexander, his book, just out this week, would have been out earlier — he had trouble getting it out of the Pentagon, the vetting process — How to Break a Terrorist: The US Interrogators Who Used Brains, Not Brutality, to Take Down the Deadliest Man in Iraq. And Scott Horton, his latest piece in Harper’s is called “Justice After Bush: Prosecuting an Outlaw Administration.”

Media Options