Guests

- Robert Kuttnerveteran economics and financial journalist, he is a founder and co-editor of the American Prospect magazine and a former investigator for the Senate Banking Committee. Author of seven books, his latest is The Squandering of America: How the Failure of Our Politics Undermines Our Prosperity.

- Max Fraserjournalist with The Nation magazine. His latest article is called 'Subprime Obama'

- Paul GunterDirector of the Reactor Oversight Project at the Beyond Nuclear, an advocacy group opposed to nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

With Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama in a dead heat, we look at their stances on some of the most pressing domestic issues with Robert Kuttner of the American Prospect, Max Fraser of The Nation and Paul Gunter of Beyond Nuclear. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: We turn now to the Democratic race, where Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama are in a virtual dead-heat that could last right up until the convention. The contest is so tight that Democratic Party chair Howard Dean has raised the possibility of a compromise if no clear nominee emerges by April.

As the Democratic race intensifies, we spend the rest of the hour looking at the candidates on some of the key domestic issues of the 2008 campaign. Both candidates have come under new scrutiny in the past few weeks.

The New York Times revealed last week that Barack Obama backed down on a bill that would have required nuclear plants to disclose radioactive releases. Critics say Obama watered down the measure after heavy lobbying by the nuclear industry, including an Illinois company named Exelon that was among his largest donors.

Days earlier, ABC News reported Hillary Clinton did not once speak out against Wal-Mart’s intensive campaign against unionization during her six years on the company’s board of directors. Clinton’s campaign biography makes no mention of her time at Wal-Mart.

AMY GOODMAN: Today, we’ll look at several domestic issues: the economy, housing crisis, Social Security, healthcare and nuclear power.

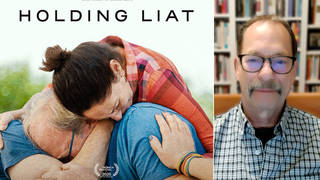

Max Fraser is a journalist with The Nation magazine. His latest article is called “Subprime Obama.” He joins us in our firehouse studio here in New York. In Washington, D.C., we’re joined by Robert Kuttner, veteran economics and financial journalist, founder and co-editor of American Prospect magazine, former investigator for the Senate Banking Committee, an author of seven books, his latest, The Squandering of America: How the Failure of Our Politics Undermines Our Prosperity.

We want to begin on the housing crisis. This is a clip of Hillary Clinton outlining her plan at the Democratic debate last month in South Carolina.

SEN. HILLARY CLINTON: I would have a moratorium on home foreclosures for ninety days to try to help families work it out so that they don’t lose their homes. We’re in danger of seeing millions of Americans become basically, you know, homeless and losing the American dream. I want to have an interest-rate freeze for five years, because these adjustable rate mortgages, if they keep going up, the problem will just get compounded. And we need more transparency in the market.

AMY GOODMAN: Robert Kuttner, let’s begin with you. Let’s talk about the healthcare plans of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama.

ROBERT KUTTNER: Well, both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama have proposed healthcare plans that are really variations on a plan designed by Jacob Hacker of Yale University, which is an attempt to get to universal coverage without having national health insurance, and it’s not bad, if you can’t have the first best, which is national health insurance. The idea is that if you have employer-provided coverage, and you like it, and it’s decent, you get to keep it. If you don’t have affordable coverage, the government will subsidize you to get coverage that’s as good as the coverage that members of Congress get.

Clinton has what’s known as a mandate. She requires people to get coverage. Obama doesn’t. Clinton and some liberal commentators, like Paul Krugman, have whacked Obama for not having a mandate. I think a mandate is a very bad idea. I think the difference between universal social insurance and a mandate is that universal social insurance, like Medicare, says that, as an American or a permanent resident of the country, you get health insurance, the same way you get Social Security. A mandate takes a social problem and makes it the individual’s problem. And in the Massachusetts version of this, on the website it says “new penalties for 2008.” You get penalized if you don’t buy health insurance, even if the health insurance that’s available is not high quality and is not affordable. Now, Hillary Clinton says that her version of this is better than Massachusetts, because they will have a substantial amount of regulation to make sure that you can’t discriminate against people with pre-existing conditions, and you can’t have excessive deductibles and co-pays. So the approach is not bad, but it’s definitely a second best. The first best would be national health insurance.

The other problem with this whole approach is that you don’t get the cost efficiencies that you get from universal health insurance, because you still have all this paperwork, you still have all the profit by private insurance companies, you still have doctors being given incentives to go for the reimbursable procedures. And as a result, the cost-containment pressures hit patients. They come in the form of less care, rather than in the form of less waste.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, I’d like to ask you, in terms of the mandates issue, because obviously both Krugman, in his various articles, and Clinton have claimed, on the one hand, that Obama does have mandates — he has mandates for coverage of all children — so that the mandates issue is not a principled issue, it’s a tactical issue as to what you think could be approved. Your sense of that?

ROBERT KUTTNER: My point is that a mandate, in a situation where the whole system is sick, makes that sickness the problem of the individual. Instead of putting a gun to people’s heads, typically people who can’t afford good quality insurance, and saying to them, “You must, under penalty of law, or pay a tax or pay a fine, go out and find decent insurance,” it’s so much better policy to just have insurance for everybody. Then there’s no question of a mandate.

I think it’s a very bad position for progressives to back into, because it signals that government is being coercive, rather than government being helpful. Now, we can split hairs and argue whether Obama is being principled or tactical, but I think his discomfort with the idea of a mandate is something that I applaud. I wish that both he and Clinton had gone all the way and said, let’s just to do this right and have national health insurance. I think they could have used this as a teachable moment. They could have bought public opinion around. Medicare is phenomenally popular. Medicare is national health insurance for seniors. Let’s have national health insurance for everybody.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s hear how Clinton and Obama discussed their plans at last week’s debate in Los Angeles.

SEN. HILLARY CLINTON: We cannot get to universal healthcare, which I believe is both a core Democratic value and an imperative for our country, if we don’t do one of three things. Either you can have a single-payer system, or — which I know a lot of people favor, but for many reasons is difficult to achieve — or you can mandate employers — well, that’s also very controversial — or you can do what I am proposing, which is to have shared responsibility.

Now, in Barack’s plan, he very clearly says he will mandate that parents get health insurance for their children. So it’s not that he is against mandatory provisions; it’s that he doesn’t think it would be politically acceptable to require that for everyone. I just disagree with that. I think we, as Democrats, have to be willing to fight for universal healthcare.

SEN. BARACK OBAMA: What they’re struggling with is they can’t afford the healthcare. And so, I emphasize reducing costs. My belief is — is that if we make it affordable, if we provide subsidies to those who can’t afford it, they will buy it. Senator Clinton has a different approach. She believes that we have to force people who don’t have health insurance to buy it, otherwise there will be a lot of people who don’t get it. I don’t see those folks. And I think that it is important for us to recognize that if, in fact, you’re going to mandate the purchase of insurance and it’s not affordable, then there’s going to have to be some enforcement mechanism that the government uses. And they may charge people who already don’t have healthcare fines or have to take it out of their paychecks. And that, I don’t think, is helping those without health insurance. That is a genuine difference.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s interesting to note something Hillary Clinton says in that clip. When she mentions a single-payer system, the audience applauds and cheers, even though it’s an option rarely seriously discussed by politicians or the corporate media. And Hillary Clinton acknowledges the applause by saying, “I know a lot of people favor [it], but for many reasons [it’s] difficult to achieve.” She doesn’t explain why she thinks it’s difficult to achieve. And polls repeatedly show a majority of Americans favor it. An A.P. poll in December found nearly two-thirds of voters want universal healthcare, in which everyone’s covered in a Medicare-type program, while more than half of voters explicitly said they support single payer. But it’s the insurance companies that are against it. Robert Kuttner, can you talk about that?

ROBERT KUTTNER: Well, one of the reasons that it’s difficult to achieve is the lack of leadership on the part of leaders like Hillary Clinton and, for that matter, Barack Obama. I mean, if you had Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama say, “You know, this is an intramural debate that we should not be having, this debate about mandates; we should do this right: we should have national health insurance,” public opinion would turn around on a dime. And instead of it being this fringe idea, all of a sudden, just because the two of them had blessed it, it would become a mainstream idea, and we would be having a debate that we should have been having all along.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’d like to turn also now to Max Fraser, who joins us. He’s with The Nation magazine. He’s written an article recently called “Subprime Obama,” where he looks at the housing crisis, and initially the article dealt with — John Edwards was still in the race — with the positions of Edwards, Clinton and Barack Obama on the housing crisis sweeping the nation. Welcome to Democracy Now!

MAX FRASER: Thanks for having me.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Could you outline the differences between — the major differences between the candidates? And it would be instructive also to talk about John Edwards’s policies, as well.

MAX FRASER: Sure. Well, when he was in the race, Edwards’s plan was by far the most comprehensive and aggressive, insofar as it really committed the government to intervening on behalf of homeowners and resolving the crisis in such a way that it would keep people from losing their homes. Edwards called for a mandatory moratorium on foreclosures, a freeze on rising interest rates, a real kind of redoubled efforts to not only regulate the mortgage markets, but financial markets generally.

Clinton and Obama fall short of that, and Obama falls short most significantly. He is the only one of the three who hasn’t called for a moratorium on foreclosures or a freeze on interest rates, which really are the most effective short-term measures that can be taken to keep homeowners in their homes. And beyond that, his plan calls for the least aggressive government intervention, the most limited spending to bail out homeowners and to especially borrowers who are at risk of defaulting on their mortgages and to help them restructure their loans in such a way that they’re affordable moving forward. And his plan actually really most relies on a pretty insignificant tax credit, which comes out to about $500 on average for homeowners, which might make a difference for those who are just barely falling behind, but not for those who are falling further and further behind.

AMY GOODMAN: Max, in your piece, “Subprime Obama,” you talk about his three main economic advisers.

MAX FRASER: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us who they are.

MAX FRASER: Well, there are these three young economists: David Cutler, Jeffrey Liebman and Austan Goolsbee. Cutler and Liebman are Harvard economists who hail from the Clinton administration. Goolsbee, who does the lion’s share of the work on this issue, comes from the University of Chicago. They’re all centrist market economists, I mean, what you would call them Clintonian in their politics, and that’s really where they’re coming from. They are oriented towards, you know, market-based solutions to social welfare issues. Cutler writes about incentivizing the healthcare industry as a way to improving care. Liebman has endorsed the partial privatization of Social Security. And Goolsbee also is one of the kind of market faithful.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Yeah, I’d like to ask you about Liebman in particular, because I think that, from what I understand, he is proposing a — has proposed for a 20 percent increase in the Social Security payroll tax to, in essence, create private accounts for all Americans. It would be like the equivalent of dues check-off for Wall Street.

MAX FRASER: Yeah.

JUAN GONZALEZ: It would be an enormous windfall for the Wall Street firms to be able to get that kind of a operation.

MAX FRASER: Right.

JUAN GONZALEZ: But it’s not clear — Obama has never said anything about this in the campaign trail, but his key adviser is known as the main proponent of this, right?

MAX FRASER: Well, one of the — a proponent of it, that’s right, entirely true. And, you know, Obama, I think what he says on the campaign trail on various issues of domestic policy are, you know, not wholly in line with where these policy advisers are, but they clearly are animating where he stands on these issues, like Social Security and the housing crisis, most notably, I think.

AMY GOODMAN: Robert Kuttner, can you weigh in here with these three economists that Max writes about in The Nation magazine, their significance, and especially on this issue of privatization of Social Security?

ROBERT KUTTNER: Well, it’s very distressing. I mean, I think it was National Journal, recently came out with a rating that showed that Obama has the most left-of-center record, voting record, in the Senate. And yet, the advisers that he relies upon are — I would call them center-right. They’re basically free-market guys who want to use markets to somehow solve social problems, which is like squaring a circle. And I was just at a board meeting of the Economic Policy Institute, which is, you know, the most effective left-of-center think tank in Washington. Except at the staff level, he is not reaching out to progressive economists. It’s a fairly narrow circle.

Same, of course, with Hillary. If anything, Hillary’s advisers are a shade more open to reaching out a little further left. And you worry that as attractive as Obama is, as inspirational as he obviously is, he might be very centrist as president, and you wonder whether this is him trying to be the Democratic version of John McCain, trying to tone it way down in order to reach out to independents, or whether this is what the man really believes, or whether he’s still a work in progress.

May I comment briefly on the housing situation?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

ROBERT KUTTNER: I think the right way to do this is to reinvent something that was done during the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, where the federal government, through a new agency, would buy back these bonds that are packages of subprime mortgages, buy them back at a discount, so that the banks and the bond holders take a big loss, and then use that savings to turn them back into affordable mortgages. You can’t do it just on the basis of a moratorium or on the basis of a freeze, because there’s no practical way to renegotiate the terms of a mortgage if the mortgage has been packaged with other mortgages into a bond. And interestingly enough, Chris Dodd, on the Senate side, who is no great progressive, is the guy who has been promoting this solution.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the ’30s saved about a million families from foreclosure. It ended up refinancing about 20 percent of all the homes in the United States. And they simply used the government’s own borrowing rate to make cheap mortgages available to homeowners who were going to lose their houses.

Now, it’s more difficult today. You can’t just refinance something. First of all, you have to turn it back from a bond into a mortgage. But I think the level at which Hillary has talked about it and Obama has talked about it is superficial and doesn’t really get at the structural problems. Now, again, the Social Security privatization issue, I don’t think it’s necessarily a terrible idea to have supplemental accounts on top of basic Social Security. The problem is that when the people who promote this take a close look at it, you realize you can’t afford to do both, so it ends up coming out of Social Security. And you really do worry about the company that Obama keeps, in terms of where he’s getting his economic advice.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Robert Kuttner, veteran economics financial journalist. His latest book is called Squandering of America. We’re also joined by Max Fraser of The Nation magazine. When we come back, we’re going to add to this discussion the issue of nuclear power and where’s the money coming from for these Democratic candidates on that issue. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to the issue of nuclear power. We’ll play a clip of Senator Clinton and Barack Obama talking about nuclear power at the Democratic debate in Utah last July.

SEN. BARACK OBAMA: I actually think that we should explore nuclear power as part of the energy mix. There are no silver bullets to this issue. We’ve got to develop solar. I have proposed drastically increasing fuel efficiency standards on cars, an aggressive cap on the amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted. But we’re going to have to try a series of different approaches.

The one thing I have to remind folks, though, of — we’ve been talking about this through Republican administrations and Democratic administrations for decades. And the reason it doesn’t change — you can take a look at how Dick Cheney did his energy policy. He met with environmental groups once. He met with renewable energy folks once. And then he met with oil and gas companies forty times. And that’s how they put together our energy policy. We’ve got to put the national interest ahead of special interests, and that’s what I’ll do as president of the United States.

ANDERSON COOPER: Senator Clinton, what is Senator Edwards — why is he wrong on nuclear power?

SEN. HILLARY CLINTON: Well, first of all, I have proposed a strategic energy fund that I would fund by taking away the tax breaks for the oil companies, which have gotten much greater under Bush and Cheney. And we could spend about $50 billion doing what America does best. It’s time we start acting like Americans again. We can solve these problems if we focus on innovation and technology. So, yes, all these alternative forms of energy are important. So is fuel efficiency for cars and so is energy efficiency for buildings.

I’m agnostic about nuclear power. John is right, that until we figure out what we’re going to do with the waste and the cost, it’s very hard to see nuclear as a part of our future. But that’s where American technology comes in. Let’s figure out what we’re going to do about the waste and the cost if we think nuclear should be a part of the solution. But this issue of energy and global warming has the promise of creating millions of new jobs in America. So it can be a win-win if we do it right.

AMY GOODMAN: The YouTube debate in Utah in July. Paul Gunter also joins us, director of the Reactor Oversight Project at Beyond Nuclear, an advocacy group that’s opposed to nuclear power and nuclear weapons. Your — can you talk a little about their positions on nuclear power and nuclear weapons?

PAUL GUNTER: Well, both Senators Obama and Clinton have basically displayed a lot of indecisiveness about all the concerns with nuclear power — its cost, the inherent dangers, the unsolved nuclear waste issue, the proliferations issue. But I think that what’s most notable about that clip is the evasiveness, the indecisiveness, that the campaigns have taken. And it’s also been reflected in legislation with both Senators Obama and Clinton.

One of the main concerns is that both Clinton and Obama have very strong backing, financial backing, from the major CEOs from the nuclear industry. For Senator Obama, the chief executive officer, John Rowe, with Exelon Nuclear, Chicago-based, largest nuclear utility in the country; and Senator Clinton has strong financial backing from David Crane, who’s the CEO for NRG Energy, which is based in New Jersey. Both Exelon and NRG right now have got applications before the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission to build new nuclear power stations in Texas. So it’s disturbing that both Senators Obama and Clinton left out nuclear in their Utah speech, but we’ve seen that basically this kind of indecisiveness, you know, being all over the board indicates that influence-peddling with the nuclear power industry is alive and well on Capitol Hill and in these presidential campaigns.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’d like to —-

PAUL GUNTER: Another major -—

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’m sorry, I’d like to ask you about John — obviously, John Edwards is out of the race, but there was a sharp difference between Edwards and either one of them on this issue, wasn’t there?

PAUL GUNTER: Absolutely. Edwards was basically raising the issues with nuclear power. He took strong positions. I mean, let’s face it, right now the industry is poised for what it calls a renaissance, what we recognize as a relapse to a failed — you know, an economic disaster, as well as raising the risks of more Chernobyls, more Three Mile Islands and the spread of nuclear weapons around the world. We need decisive leaders, leadership in a twenty-first energy policy, rather than to go back to the failure of the twentieth century, particularly focusing on, you know, the hegemony between coal, oil and nuclear. So, you know, Edwards was making those statements, was — you know, I think he was demonstrating that leadership. And both Obama and Clinton are hedging.

Actually, both are, you know, remaining open to one of the largest managerial disasters in US business history, where, you know, we — if we repeat that mistake, it’s a little like seeing Lucy offer Charlie Brown this football again. You know, we know what’s going to happen. Why the Clinton and Obama campaigns should remain open to, you know, making that mistake again and falling flat on our back, while we’re facing the imminent and rising risks of rapid climate change — we need leadership now to make decisive policy that sets us on a course where, you know, we’re not going to be faced with climate change, nuclear waste and more nuclear weapons.

AMY GOODMAN: Paul Gunter, in looking at this New York Times piece of February 3rd by Mike McIntyre, he also talks about the chief political strategist of Barack Obama, David Axelrod, who has worked as a consultant to Exelon. A spokeswoman for Exelon said Axelrod’s company had helped an Exelon subsidiary, Commonwealth Edison, with communications strategy periodically since 2002, but had no involvement in the leak controversy or other issues. If you can you comment on that and what the leak controversy was all about?

PAUL GUNTER: Well, you know, basically what the story is is that, you know, for more than a decade, Exelon Nuclear, chiefly at nuclear power stations in Dresden and Braidwood, have been experiencing leaks of radioactive tritium into groundwater, where, at least at Braidwood, on two occasions, more than three million gallons of radioactive water was spilled out onto the surface, where it soaked into groundwater, ran offsite over shallow drinking water wells in neighboring residents, and did not disclose these spills until a constituency of community organizers began to raise this issue, noting that they were really concerned about not only these spills, but cancer clusters and pediatric brain cancers that —- around the facilities. And, you know, I think the issue -—

AMY GOODMAN: We just have thirty seconds, so if you could —-

PAUL GUNTER: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —- tell us what — how Barack Obama was involved with this?

PAUL GUNTER: Well, you know, they came to Barack Obama, and basically he set out with strong legislation that would have required mandatory reporting by these utilities to local communities, you know, to basically alert them to these leaks. But as the influence of the Nuclear Energy Institute and Exelon began to come into play, the legislation was basically pulled — all the teeth were pulled out of it and, you know, again leaves these communities vulnerable.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Paul Gunter, we’re going to leave it there. I want to thank you very much for being with us. He is director of the Reactor Oversight Project at Beyond Nuclear an advocacy group opposed to nuclear power and nuclear weapons. Max Fraser of The Nation, and Bob Kuttner of American Prospect.

Media Options