Related

Topics

Guests

- Almerindo OjedaProfessor of linguistics at UC Davis and principal investigator of the Guantanamo Testimonials Project.

This weekend, three former Guantanamo prisoners will talk for the first time to a US audience about their prison experiences. We speak to Almerindo Ojeda, UC Davis professor and principal investigator with the Guantanamo Testimonials Project, a UC Davis-based effort to catalog accounts of prisoner abuse. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The US prison camp at Guantanamo has become a symbol of the so-called “war on terror” since it was created more than six years ago. Over 800 men and boys, so-called “enemy combatants,” have been held without charge at Guantanamo since January 11, 2002. Not one of these prisoners has been put on trial. Hundreds have been released without charge after years behind bars. Four prisoners have committed suicide; many others have tried to do that, as well.

This weekend, three former Guantanamo prisoners will talk for the first time to a US audience about their prison experiences. The event is being organized by the Guantanamo Testimonials Project, a University of California, Davis-based effort to catalog accounts of prisoner abuse. I’ll interview the three former prisoners via videoconference from Sudan. All three men — Adel Hassan Hamad, Salim Adam and Hammad Ali Amno Gad Allah — were classified and imprisoned as enemy combatants and held without charge for years before being released without explanation.

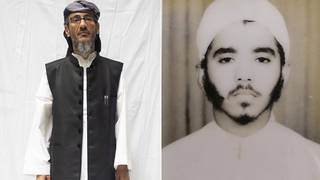

Of the three, Adel Hamad is the most well known. He was a hospital administrator in Sudan when he was arrested and imprisoned at Guantanamo for over five years. During his imprisonment, activists here in the United States had started a campaign to secure his release called Project Hamad. The group’s website included a popular video that told Adel Hamad’s story. it featured family members, like his brother-in-law, Adil Al-Tayib.

ADIL AL-TAYIB: [translated] The way we knew Adel, his situation and his life, we did not believe that Adel would be imprisoned for five years. Now five years have passed, and no one knows what will happen next. We hope that Adel will come back and be united with his family again.

AMY GOODMAN: The web video put out by Project Hamad also included actor Martin Sheen.

MARTIN SHEEN: Hello, I’m Martin Sheen. We Americans must not allow fear to overcome our faith in the laws and values that have made this country great, like the right to a fair hearing in a court of law, like the right to know and respond to the charges against you, like the right not to be detained indefinitely, even by order of the President. All of these rights are protected by the United States Constitution.

I’ve been asked to speak to you about Adel Hamad, Detainee no. 940 in Guantanamo. Mr. Hamad was abducted from his home nearly five years ago during a sweep of foreigners in Pakistan and sent to Guantanamo, where he is still being held without a court hearing, even though all the evidence gathered confirms he is an innocent man, a hard-working hospital administrator. Meanwhile, Adel Hamad’s wife and four children in Sudan continue to suffer without him. She has written to President Bush asking for justice, but has received no reply. No one should be detained without a court hearing just on the word of a president.

AMY GOODMAN: Actor Martin Sheen, talking about former prisoner Adel Hamad, who was held at Guantanamo for five years. He’s one of the three former Guantanamo prisoners I’ll be interviewing from Sudan via video conference tomorrow at University of California, Davis.

Almerindo Ojeda is a professor of linguistics at UC Davis and principal investigator of the Guantanamo Testimonials Project. He joins us here in Los Angeles. Welcome to Democracy Now!, Professor Almerindo.

ALMERINDO OJEDA: Good to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about this Guantanamo Testimonials Project.

ALMERINDO OJEDA: The Guantanamo Testimonials Project is an initiative that we created in 2005, and the goals of that initiative are to gather testimony of prisoner abuse at Guantanamo, to organize it in meaningful ways, to make it widely available online, and to preserve it there in perpetuity. We have been at it for three years, and we’ve gathered hundreds of testimonies from prisoners and guards, lawyers, all sorts of people that have had firsthand experience at the prison.

AMY GOODMAN: And what inspired this?

ALMERINDO OJEDA: What inspired this, well —-

AMY GOODMAN: The event that is happening this weekend.

ALMERINDO OJEDA: Oh, an old student of ours in Davis went back to the Sudan to work. He was a Sudanese American and became a journalist there. And he got to know three former prisoners from the Sudan, and he contacted me and saying if we wanted to talk to them. And we said, “Of course.”

AMY GOODMAN: And what was their response when you first contacted these prisoners? How long have they been out? How long have they been out of Guantanamo?

ALMERINDO OJEDA: They’ve been out since 2007, so a year, and a little bit more, perhaps. They were imprisoned for years, some of them without any explanation -— really none of them with any credible explanation. And they’re anxious to tell their stories to the American public.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you give some description of these three men?

ALMERINDO OJEDA: Sure. One of them is Adel Hamad, whom you talked about before. He was a hospital administrator, indeed. He claims to have been tortured in Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan before being transferred to Guantanamo. He was then tried on secret evidence and cleared for release in 2004, but action wasn’t actually released until 2007.

AMY GOODMAN: So he was held for three more years?

ALMERINDO OJEDA: After being cleared in these dubious trials that they get in the prison.

Another one is Hammad Amno. He claims to have witnessed prisoner abuse at Guantanamo, beatings. There apparently was some kind of protest after the Koran was withdrawn from a prisoner who was held in isolation. So he started protesting, and the whole wing of the prison started protesting. And he witnessed — Hammad Amno did — guards come in and beat prisoners, he claimed.

And the third is Salim Mahmud Adam. He worked at an orphanage and was arrested also through Bagram, taken to Guantanamo. And he claims to have been witness — to have witnessed harsh interrogations with beatings, the loud music, the flashing lights and the whole works.

AMY GOODMAN: And what has been the response on campus to this unprecedented event, this kind of bridge between UC Davis and Sudan?

ALMERINDO OJEDA: Very supportive. The university has been very supportive of the effort, and they have facilitated all the technical connections and publicity for the event, so I’m very happy.

AMY GOODMAN: You head the Center for Human Rights at UC Davis?

ALMERINDO OJEDA: That’s right. That’s right. We started it at about the same time as the Guantanamo Project in 2005. We were trying to look at human rights in the Americas, understood broadly, North, Central and South. And our first focus was the war on terror and its effects on the American continent, from Maher Arar in Canada to the effects on the indigenous populations in South America that are an easy target on the so-called war on terror.

AMY GOODMAN: Maher Arar being the Canadian citizen —-

ALMERINDO OJEDA: Correct.

AMY GOODMAN: —- who was picked up at Kennedy Airport on his way home from family vacation —-

ALMERINDO OJEDA: On his way back to Canada, right.

AMY GOODMAN: —- and he, through extraordinary rendition, was sent off to Syria, where he was tortured, and after ten months released back in the United States.

ALMERINDO OJEDA: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: Now the Canadian government has just awarded him $10 million.

ALMERINDO OJEDA: But we won’t talk to him, and we won’t recognize his plight in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you for being with us. As we brought this part of the discussion, we’re going to turn to a clip of one of the more well-known prisoners at Guantanamo. His name is Sami al-Hajj. He spent nearly six years — well, over six-and-a-half years in prison, almost six years at Guantanamo itself, without charge or trial, before being released earlier this month. He had been on a more-than-yearlong hunger strike to protest his imprisonment. After arriving in Khartoum, he spoke out against the treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo in an interview that was broadcast on Al Jazeera.

SAMI AL-HAJJ: [translated] I’m very happy to be in Sudan, but I’m very sad because of the situation of our brothers who remain in Guantanamo. Conditions in Guantanamo are very, very bad, and they get worse by the day. Our human condition, our human dignity was violated, and the American administration went beyond all human values, all moral values, all religious values. In Guantanamo, you have animals that are called iguanas, rats that are treated with more humanity. But we have people from more than fifty countries that are completely deprived of all rights and privileges, and they will not give them the rights that they give to animals.

For more than seven years, I did not get a chance to be brought before a civil court. To defend their just case and to get the freedom that we’re deprived of, they ignored every kind of law, every kind of religion. But thank God. I was lucky, because God allowed that I be released. Although I’m happy, there is part of me that is not, because my brothers remain behind, and they are in the hands of people that claim to be champions of peace and protectors of rights and freedoms.

But the true just peace does not come through military force or threats to use smart or stupid bombs or to threaten with economic sanctions. Justice comes from lifting oppression and guaranteeing rights and freedoms and respecting the will of the people and not to interfere with a country’s internal politics.

AMY GOODMAN: Sami al-Hajj, interviewed by Al Jazeera from Khartoum, Sudan, where he was released. He was imprisoned by the United States for over six years. Most of that time, he was in jail at Guantanamo in Cuba. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report. The interview we will do with other Sudanese prisoners who’ve just been released from Guantanamo over the last year will take place at University of California, Davis on Saturday night at the Sciences Center. For more information, you can go to our website at democracynow.org.

Media Options