A landmark case is returning to a New York district court that seeks millions of dollars in reparations from corporations that supported and profited from South African apartheid. The suit is filed on behalf of thousands of apartheid victims under the Alien Tort Claims Act. It seeks damages from the companies for doing business with the apartheid government despite international sanctions and boycotts. The companies include the oil giants BP and ExxonMobil, banks such as Citigroup and UBS, and the car giants General Motors and Ford Motor. We speak with South African poet and activist, Dennis Brutus. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN:

A landmark case returns to a New York district court today seeking millions of dollars in reparations from corporations that supported and profited from South African apartheid. The suit is filed on behalf of thousands of apartheid victims under the Alien Tort Claims Act. It seeks damages from the companies for doing business with the apartheid regime despite international sanctions and boycotts. The companies include the oil giants BP and ExxonMobil, banks such as Citigroup and UBS, and the car giants General Motors and Ford Motor.

The case was initially dismissed in November 2004 but reinstated last October. The Supreme Court was set to rule on the case in May but sent it back to district court after four justices disclosed they own shares in some of the companies named in the suit. District Court Judge John Sprizzo will preside over the hearings. He made the initial ruling to dismiss the case nearly four years ago.

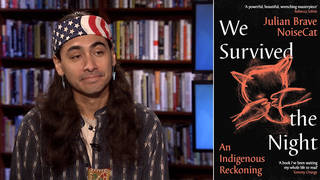

My guest is one of South African apartheid victims who came to New York to testify. In apartheid South Africa of the ’60s, the poet Dennis Brutus was an outspoken activist against the racist state. He helped secure South Africa’s suspension from the Olympics, eventually forcing the country to be expelled from the Games in 1970. Arrested in 1963, he was sentenced to eighteen months of hard labor on Robben Island, off Cape Town, with Nelson Mandela.

Dennis Brutus was banned from teaching, writing and publishing in South Africa. His first collection of poetry, Sirens, Knuckles and Boots, was published in Nigeria while he was in prison.

After he was released, Dennis Brutus fled South Africa on a, at that time, Rhodesian passport in ’83. After a protracted legal struggle, Dennis Brutus won the right to stay in the United States as a political refugee, has since become Professor Emeritus in the Department of Africana Studies at the University of Pittsburgh and professor at South Africa’s University of KwaZulu-Natal. Dennis Brutus celebrates his eighty-fourth birthday later this year. He joins us now in the studio.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Thank you, Amy. Good to be here.

AMY GOODMAN:

Well, you are sitting in our firehouse studio, just down the road from the court you will be in in a few minutes. Can you tell us about the significance of this case, Dennis Brutus?

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Well, of course, it’s a fight for South Africans, the victims of apartheid. But when we challenge the behavior of the corporations, it seems to me that relates also to corporations in other parts of the world. So we’re really doing a local attack, but also a global attack. I think the two go together.

AMY GOODMAN:

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, where people came and testified, they got amnesty if they told the truth, even if they were talking about massacres, the brutal murders of South Africans. The corporation part of it, track of it, didn’t get much attention.

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Right, although they were invited to testify and indeed to acknowledge their complicity, but they just turned a deaf ear to it. So, in fact, they got off very lightly.

AMY GOODMAN:

Can you talk about these corporations and what they did? How did they help the apartheid regime?

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Right. Well, I grew up in Port Elizabeth, for instance, which was the headquarters both of Ford and GM, and they were using black labor, but it was very cheap black labor, because there was a law in South Africa which said (a) blacks are not allowed to join trade unions, and (b) they’re not allowed to strike, so that they were forced to accept whatever wages they were given. They lived in ghettos, in some cases near where I lived actually in the boxes in which the parts had been shipped from the US to be assembled in South Africa. So you had a whole township called Kwaford, meaning the place of Ford, and it was all Ford boxes with the name “Ford” on them, because they were addressed to Ford in Port Elizabeth.

Now, what is striking is that when I appeared before the GM stockholders’ meeting in Detroit and I raised the question on behalf of the American churches, “What do you pay the blacks in South Africa?” the stockholders voted they didn’t want to be told, a 98 percent vote which said, “We don’t want to be told.” So, obviously, the complicity was both at the top executive level, but also with the stockholders themselves.

AMY GOODMAN:

When did you ask that question?

DENNIS BRUTUS:

At that time, I was teaching at Northwestern University. I mean, early ’70s.

AMY GOODMAN:

The other corporations that you’re seeking damages against in this landmark case, ExxonMobil and BP?

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Well, the same sort of thing: cheap labor, exploited labor and no levels of managerial or management position at all. So it’s consistent discrimination against blacks on the basis of race, which pays off, of course, in starvation wages. In some cases, the corporations took out space in the newspapers to announce that “We are loyal citizens of South Africa, we accept the laws of South Africa.” So they were actually declaring the fact that, for them, apartheid was a very good system, and it was a very profitable system.

AMY GOODMAN:

The South African government is not supporting you in this lawsuit.

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Right.

AMY GOODMAN:

Has actually obeyed the Bush administration demands that they oppose the lawsuit.

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Right, they filed a brief asking the judge to dismiss our application. This was filed by the South African minister of justice on behalf of the government. When he stepped down, the minister who took over after — Maduna was succeeded by someone called Bridgette Mabandla — she reaffirmed the application, that the application that we had made should be dismissed. She said there should be no reparations.

AMY GOODMAN:

Your response?

DENNIS BRUTUS:

Well, it seems to me it’s perhaps the most dramatic example we have of a government choosing to support the corporations in opposition to its own citizens. So when the citizens are victims and the corporations are the beneficiaries, the government comes out in support of the corporations.

AMY GOODMAN:

We’re going to have to leave it there, but we will follow the case, and we’ll report on what happens this morning.

Media Options