Topics

Guests

- Greg Grandinprofessor of Latin American history at NYU and author of Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Rise of the New Imperialism.

A former priest known as the “Bishop of the Poor,” Fernando Lugo is the first Paraguayan president since 1946 not to be from the conservative Colorado Party. He has pledged to give land to the landless and fight corruption. We speak to Greg Grandin, professor of Latin American history at NYU. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In one of his first acts in office, Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo has appointed an Indian woman to be minister of indigenous affairs. Margarita Mbywangi is a forty-six-year-old Ache tribal chief who was captured in the jungle as a girl and sold into forced labor several times with the families of large landowners. She spent the early part of her career as an activist defending her people’s land. Her appointment makes her the first indigenous person to oversee ethnic Indian affairs in Paraguay. President Fernando Lugo formally named her to his Cabinet Monday as he began setting up his government following his inauguration on Friday.

A former priest known as the “Bishop of the Poor,” Lugo is the first Paraguayan president since 1946 not to be from the conservative Colorado Party. He has pledged to give land to the landless and fight corruption.

He is also the first bishop ever to become president of a country. Lugo says he was influenced by the liberation theology of the ’60s. Both Paraguay and the Vatican ban clergy from seeking political office, so Lugo resigned in December of 2006. He said he would not marry during his five-year mandate. His sister will therefore act as the country’s first lady.

On Saturday, Lugo traveled to San Pedro, the province where he spent eleven years as bishop. He was accompanied by the Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, who has promised to provide Paraguay with a steady supply of fuel. Appearing on stage together, Chavez gave Lugo a replica of South American independence hero Simon Bolivar’s sword. Brandishing the sword in his hand, Lugo pledged to fight for justice and end corruption.

PRESIDENT FERNANDO LUGO: [translated] This was used by Bolivar. We, too, will use it. And I say this very seriously. We will use it against corruption, bribes and those that stole from the country. They deserve justice, and this is the sword of justice. Bolivar’s sword is something symbolic and emblematic.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg Grandin is a professor of Latin American history at New York University and author of Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Rise of the New Imperialism, joining us now in our firehouse studio.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

GREG GRANDIN: Hi, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg, talk about the significance of Fernando Lugo becoming president of Paraguay.

GREG GRANDIN: Oh, it’s enormously significant. I mean, just think of Latin America. In some ways, Lugo completes the set. Latin America is governed by a series of leftist or center-left presidents, that in — each one representing different currents within the Latin American left. You have indigenous rights organizers. You have social democrats. You have trade unionists. You have nationalist military populists. And now you have a liberation theologian. In some ways, he completes the ascension of the return of the Latin American left.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about his history, his biography, Lugo.

GREG GRANDIN: Well, he was born in 1951, and in some ways his life spans two different very distinct periods in Latin American history. He came of age when liberation theology was spreading across the continent. He became a priest in 1977. But he was becoming — entering into maturity in the late ’60s, when the Catholic Church, Christian-based communities, particularly in Brazil — Brazil was a big center of liberation theology — was affirming a commitment with the poor, developing a critique of international capital, understanding exploitation and poverty as what liberation theologians called social sin. And then he became politically active in Paraguay in the 1980s and 1990s, when the moment when these new social — it’s particularly peasant movements in Paraguay were emerging and taking the lead, emerging as the vanguard and the opposition to the Colorado Party.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the Colorado Party. How did it start?

GREG GRANDIN: Well, the Colorado Party is one of the historic Paraguayan parties. Its roots go back decades, in some ways, and it’s been in power for sixty-one years, since the late 1940s. And you could think of its rule divided into two periods. The first period was dominated by Alfredo Stroessner between 1950 — he ruled between ’54 and ’89, a classic Cold War dictator, very much involved in setting up Operation Condor with other Latin American anti-communist dictators and terrorist states.

AMY GOODMAN: Which was — Operation Condor?

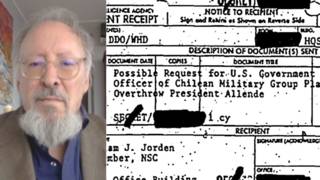

GREG GRANDIN: Operation Condor, you can think of as a consortium of death squad intelligence apparatus in one country after another. It basically brought together all of these distinct death squad units in Chile, in Paraguay, in Argentina, in Uruguay.

AMY GOODMAN: Radiating from Pinochet?

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, Pinochet and radiating, yeah, through Chile. It started in 1975, and they began to coordinate their work in order to confront what they imagined to be an international opposition, not just terrorize the democrats and reformists and nationalists within countries and opposition leaders within countries and activists, but also anywhere. Operation Condor famously conducted operations in Europe, in the United States and elsewhere. It was really a transnational terror operations. In some ways it was also facilitated through the CIA and through the United States military providing information through bases in Panama and elsewhere.

And then the second period of Colorado rule was a very fitful and corrupt democratization process after 1989, with the — that corresponded to the end of the Cold War up until the election in April of Lugo. It’s marked by violence and corruption and an ongoing, ongoing political turmoil, and again, the emergence of these new social movements, which became the main, the most vital opposition movement to the Colorado Party rule.

AMY GOODMAN: So he runs for president. He’s bishop.

GREG GRANDIN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: What did that mean? And what does it mean to — well, he can no longer — he has to resign as bishop.

GREG GRANDIN: Yes, he resigned as bishop, and he tried to resign from the Catholic Church. And for a while, the Catholic Church rejected his resignation as a priest, and then they worked out some kind of accord in which he could run. And for a while, opponents in Paraguay were trying to rule his candidacy as unconstitutional, because he was a — because he remained a Catholic priest.

It was enormously important, because he was able to unite movements. His coalition, it’s a very broad coalition, comprising something — ten political parties including the more conservative and establishment opposition party to the Colorados, the Authentic Radical Liberals, which is another historic Paraguayan party, but then also a broad array of smaller leftist party, but also twenty social movements.

And the heart of that is in some ways the peasant movement, the campesino movement, which he was very much involved in during his — he was the bishop of the province of San Pedro, which is to the northeast of Asuncion, the capital of Paraguay. And that’s where the heart of a lot of the soybean production, a lot of the worst of the dispossessions that happened since the — well, the dispossession, land dispossessions, really start in two periods. One is under Stroessner, the dictatorship, in which he hands out vast tracts of land under a so-called land reform to military cronies. And then, with the rise of soybeans and agro-industry, it really fuses with corporate agro-industry and continues into the 1980s and 1990s an enormous dispossession of something like 300,000-400,000 landless peasants in Paraguay.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did — what was the platform that Lugo ran on?

GREG GRANDIN: He ran on three basic points. One — two of them had broad support throughout the political class in Paraguay. One was governability, ending corruption, ending the Colorado — sixty years of Colorado rule, trying to reform the government and make the Paraguayan government a more functionable — in which he was able to provide services to the majority of Paraguayans, institute a social welfare state to some degree.

Second one had to do with hydroelectricity. Paraguay doesn’t have oil. It doesn’t have natural gas. What it does have is enormous amounts of hydroelectricity, basically two dams that were built in the 1970s, and under the — one in a joint agreement with Brazil and the other one with Argentina. Under the terms of the construction of those dams, Brazil and Argentina get the surplus of whatever hydroelectricity Paraguay doesn’t use at below cost. This is an enormous diversion of wealth that could be sold on the international market. Paraguay produces 70 billion kilowatt hours of electricity. It uses six billion. So that means Brazil and Argentina get the rest at almost cost. And so, he ran on what could be called “hydronationalism,” an attempt to renegotiate those contracts and those arrangements with Brazil and Argentina. Those two things had broad support among the political opposition in Paraguay.

The third plank was land reform, and this is much more contentious, and this is where — this is the issue that I think is going to make or break his presidency.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain further.

GREG GRANDIN: Well, as I said, his social base is these campesino movements, these [inaudible] social movements, civil society movements around land issue, 300,000 peasants without land, landless peasants, many of them displaced either directly by paramilitaries or the military in the ’80s and ’90s, others by the widespread use of pesticides and other toxic agricultural inputs, which have just poisoned livestock and human beings and water and drove people off land. And so, what you see in Paraguay is a kind of coalition between the old tradition oligarchy, landed oligarchy, and these new corporate agribusinesses, a lot of them from the United States — Archer Daniels — ADM, Cargill, DuPont — but also a number of agro-industries from Brazil. In some ways, Paraguay is within Brazil’s sphere of influence, and so there’s going to be — so, attempting to reverse that is going to be the key difficulty and challenge for his presidency.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to talk about Venezuela and Paraguay. Of course, Hugo Chavez went to Lugo’s inauguration. This is the two of them in Asuncion, the capital of Paraguay, singing together at a noisy concert.

[clip of Presidents Lugo and Chavez singing]

AMY GOODMAN: Presidents Lugo and Hugo Chavez.

GREG GRANDIN: It looked like Peter from — Peter, Paul and Mary were there, didn’t it?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, here is Hugo Chavez saying he will give Paraguay all the oil he needs. What about that?

GREG GRANDIN: Oh, well, oil is key, because, in many ways, the promise and the expectation that you can receive a steady supply of oil without major price hikes, depending on the global market, is key to any kind of developmental project in planning, in economic planning. In many ways, the oil spikes in the late 1970s are what destroyed the earlier model of developmentalism, state developmentalism, paving the way for neoliberalism and free market capitalism and financialization and ending all that state developmentalism. So if a country can depend on a steady supply of oil and knows what the price is going to be over a given period of time, it’s essential to economic planning. So this is the key thing. Chavez offered him, I think, 25 million barrels a day, which I believe is what Paraguay uses, so it would be 100 percent of its oil supply.

AMY GOODMAN: And the significance of Margarita Mbywangi, the indigenous affairs — the new indigenous affairs minister?

GREG GRANDIN: Well, she is from an indigenous tribe of just a few hundred people that are left in this indigenous tribe. And there’s about 100,000 indigenous Paraguayans. Paraguayans are — most are self-identified mestizos; 95 percent, 96 percent identify as mestizos, a mix of European and indigenous ancestry. But there’s about 100,000 — a little bit more than 100,000 indigenous people in Paraguay. And they’re there on the bottom of the social ladder in terms of state services, in terms of economics, in terms of poverty. And she, herself, was sold into slavery.

I mean, when people talk about Latin America being feudal, Paraguay is feudalism on steroids. It’s controlled by maybe a few hundred families. Three percent, two percent of the population owns or controls 90 percent of the cultivatable land and cultivated land in Paraguay. And she’s an incredible story. She was literally sold from one hacienda family to another growing up. She managed to escape that and become an indigenous rights activist and a land rights activist. And Lugo just appointed her as the minister of indigenous affairs, which is highly symbolic.

AMY GOODMAN: In April, a few days after Lugo won the presidential election in Paraguay, Democracy Now! co-host Juan Gonzalez had a sit-down interview with the president of Bolivia, Evo Morales. He asked Morales about the significance of Lugo’s election.

PRESIDENT EVO MORALES: [translated] Well, first of all, I would like to tell my colleague, brother, President-Elect Fernando Lugo, welcome to the Axis of Evil. But I am so sure that it is an axis for humankind, liberating democracies that are not subjugated. They should continue to grow in Latin America. The next will certainly be in Peru and Colombia, that there be governments or presidents who are subordinated to their peoples and not to the empire. So I am very pleased at his election.

AMY GOODMAN: Bolivian President Morales: “Welcome to the Axis of Evil.”

GREG GRANDIN: Yeah, well, again, think of Latin America. There’s no other region in the world in which the majority of governments are ruled by governments — by politicians that expressly base their authority on advancing a classic left agenda, ending inequality, advancing human dignity, advancing national solidarity. It’s amazing.

And there’s been a lot of — there’s been considerable attempt by political scientists and government officials in this country to drive a wedge between the so-called good left in the bad left. But it’s been impossible to do, because Latin Americans themselves don’t buy that division. Certainly, there’s plenty of differences between Hugo Chavez-style populism and somebody like Michelle Bachelet, social market reformism, but they share a common agenda. And I think that Latin American — these politicians in Latin America see that. So when Lugo equally praises Bachelet and equally praises Chavez, he’s not being disingenuous. He understands that they’re coming out of a same tradition. They face enormous challenges, specific challenges in each country. But they’ve remained relatively committed to this left agenda.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Greg Grandin, I want to thank you very much for being with us. Greg Grandin, professor of Latin American history at New York University, NYU, author of Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Rise of the New Imperialism.

Media Options