Guests

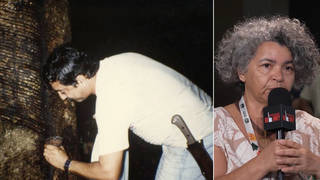

- Joycelyn Gill-Campbellfull-time organizer with Domestic Workers United, she is from Barbados and a former nanny in New York City.

The Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, if passed, would amend New York state labor law and guarantee the over 200,000 nannies and housekeepers in New York state a living wage, overtime pay, sick leave, severance and health benefits, and protection from employment discrimination. It would be the first such bill in the country to challenge the exclusion of the nearly two million domestic workers countrywide from national labor law and set an important precedent for other states. We speak with a nanny-turned-organizer. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ:

With the New York state legislature in Albany in chaos, we turn now to one of the bills whose future is at stake, the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights. It’s a bill that pertains to New York, but if it passes, it could be the first such bill in the country to challenge the exclusion of the nearly two million domestic workers countrywide from national labor law and set an important precedent for other states. The bill has several supporters in the Assembly and the Senate, and on Thursday Governor Paterson said he would sign it if it passes the legislature.

The bill would amend New York state labor law and guarantee the over 200,000 nannies and housekeepers in the state a living wage, overtime pay, sick leave, severance and health benefits, and protection from employment discrimination.

AMY GOODMAN:

The Domestic Workers Bill of Rights was drafted by members of the group Domestic Workers United five years ago. Well, today, notwithstanding the latest upheaval in the New York state legislature, as the bill stands on the threshold of being taken up by the legislature, we’re joined by a former nanny in New York City, originally from Barbados, now a full-time organizer with Domestic Workers United. Her name is Joycelyn Gill-Campbell.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Joycelyn. Lay out what this Bill of Rights is.

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

The Bill of Rights is asking for paid vacation, sickness benefit, severance pay, notice prior to being fired. In other words, we are asking for what other workers are getting. You know, we want to be treated like real workers.

JUAN GONZALEZ:

And how has the battle gone throughout to get the bill to the legislature, and what were the prospects that you had before this chaos erupted this week over who controls the New York State Senate?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

Actually, the process of having the bill gone this far is it wasn’t really easy, because when we first started this bill, we had to be educating the legislators and the public to the abuses and the exploitations that workers were facing. And, you know, right now, with all that is going on in Albany, we are still very optimistic about having this bill pass out of legislation on to the governor.

AMY GOODMAN:

Can you, Joycelyn, tell us your story?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

Well, actually, my story, being involved as a domestic worker, is, when I first came to this country, I was enrolled in the Allen school doing — the Allen nursing school. And while studying there, I took the job of babysitting, you know, to help with other expenses. And I was working for a very well-to-do family, and I was taking care of one little girl. And they had two dogs, and one of the dogs developed cancer and could not walk. So they went out, and they bought a double stroller. So, as I speak to you now, you get the picture. So, at that time, I was made to wear a white uniform. So it meant that I had to push the dog and the little girl in the stroller in a white uniform through the streets of Manhattan. Now I am not against people being animal lovers, but the fact is that, having to work more than forty hours per week, I was only paid $271.50 every two weeks.

AMY GOODMAN:

Every two weeks?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

Every two weeks, which is equivalent to $135.25.

AMY GOODMAN:

So you were being paid two dollars-something an hour?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

An hour, less than minimum wage.

AMY GOODMAN:

And how would the Bill of Rights change this?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

The Bill of Rights is going to set standard guidelines for employers and protection for the workers. In the same time, it’s going to put that — those guidelines will tell the employers that you cannot ignore the rights of the domestic worker any longer, because there are set guidelines. You have to follow this. You know, because right now, at this 2000s, you find that we still have workers working for less than minimum wage. We have workers that are working for less than $300 per week. We have workers that are working fifty and sixty hours in this industry a week, you know.

JUAN GONZALEZ:

And how difficult has it been to organize Domestic Workers United, given the fact that many of those domestic workers are immigrants and some may be abused by their employers, because they may be undocumented while they’re in the country?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

At first, when we first started doing outreach, it was so difficult, because the workers were afraid. And we do recruit them through a series of outreach: the playgrounds, even the churches, even the bookshops, stores where you’ll find a nanny browsing through, like the Gap. We do street outreach. We do — Jews for Racial and Economic Justice came aboard with us, and they’ve been doing employer organizing. And some employers have been allowing their members — their workers to become members, and some are not. It has not really been easy, like I said, because sometimes when you’re doing outreach, the workers are afraid to speak to you. So we have to reassure them, you know, that the employers do not have to know that they are members of the organization.

I remember when I first came to the organization, the membership was like twenty-five members for a general meeting, which is on the third Saturday in every month. But some Saturdays now, we have at least a hundred members coming out.

AMY GOODMAN:

When you said that you worked forty hours a week, it’s not quite that, was it, because you slept there at night. I was reading testimony of yours, talking about sleeping in the den next to the sick dog.

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

I only slept over at weekends. You know, I wasn’t a live-in. It was only on weekends.

AMY GOODMAN:

And you had to take care of the dog?

JOYCELYN GILL-CAMPBELL:

And then, one of the dogs — the cat scratched the dog in his eye, and he had to be given eye drops. So I was sleeping in the den, and the dog in a cage. So, through the night, every four hours, I had to wake up to put the eye drops into the dog eyes, which was very dehumanizing, you know.

AMY GOODMAN:

Well, we will certainly continue to follow this issue. With the chaos in the New York state legislature, it’s unclear on every level what’s going to happen, but the Domestic Bill of Rights, if passed, could be a model for what happens around the country. Joycelyn Gill-Campbell, thanks very much for being with us, full-time organizer with Domestic Workers United, from Barbados, former nanny here in New York City.

Media Options