Guests

- Clifford Alexander.former Secretary of the Army under President Carter and the first African American to hold the post. He also served in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations as a presidential adviser on civil rights, and he has worked for years as an attorney in Washington, DC.

- Nathaniel Frankauthor of Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. He’s also senior research fellow at the Palm Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, which does research in the areas of gender, sexuality and the military.

As a presidential candidate, Barack Obama vowed to work to overturn the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy on gays and lesbians in the military. But since taking office, Obama has made no specific move to do so. Last week, the Supreme Court decided not to hear a challenge to “don’t ask, don’t tell.” In a brief, the Obama administration had said the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy is “rationally related to the government’s legitimate interest in military discipline and cohesion.” We speak to former Army Secretary Clifford Alexander and Nathaniel Frank, author of Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to talk now about the military policy. As a presidential candidate, Barack Obama vowed to work to overturn the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy on gays and lesbians in the military. But since taking office, Obama has made no specific move to do so. Last week, the Supreme Court decided not to hear a challenge to “don’t ask, don’t tell.” In a brief, the Obama administration had said the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy is “rationally related to the government’s legitimate interest in military discipline and cohesion.”

Conceived in 1993 by the Clinton administration, “don’t ask, don’t tell” allows gay military personnel to serve as long as they don’t disclose that they’re gay or engage in homosexual conduct. Over the past fifteen years, the policy has led to the dismissal of nearly 13,000 members of the US armed forces, and it’s still US law under Commander-in-Chief Barack Obama.

Nathaniel Frank is the author of Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. He’s also senior research fellow at the Palm Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, which does research in areas of gender, sexuality and the military. He’s joining me from Chicago.

We’re also joined on the telephone from Washington, DC, by Clifford Alexander. He is the former Secretary of the Army under President Carter, the first African American to hold that post. He also served in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations as a presidential adviser on civil rights, and he has worked for years as an attorney in Washington, DC. And, oh, by the way, on this day leading into Father’s Day, he happens to be the father of Elizabeth Alexander, who read her problem for the inauguration of President Barack Obama.

Happy Father’s Day, Clifford Alexander.

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER: Thank you, Amy Goodman.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s good to have you with us. Talk about “don’t ask, don’t tell” — you were Secretary of the Army — and where you stand on this today, what you’re doing about it.

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER: The policy is an absurdity and borderline on being an obscenity. What it does is cause people to ask of themselves that they lie to themselves, that they pretend to be something that they are not. There is no empirical evidence that would indicate that it affects military cohesion. There is a lot of evidence to say that the biases of the past have been layered onto the United States Army.

It has several negative ramifications. One is the fact that the people who are presently serving, and that’s thousands and thousands who are gays and lesbians, they have to lie every day. It’s like asking a Jewish person to act like he or she is a Muslim, or asking a Catholic to act like he or she is Buddhist, taking their fundamental values and exchanging it for silence. A second issue is, of course, that people who would want to serve in this nation’s armed services, because of their specific orientation sexually, they will not do so because they don’t want to engage in the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

What we need to have, I think immediately, is an urgency about this issue and an urgency that goes well beyond the President of the United States, but also to the Congress, because it’s my understanding that the legislation has to be repealed with other legislation. So, as I understand, in the House there is some movement in that direction, but what I do not sense is that there is an urgency about this issue on the part of Americans, whatever their particular sexual orientation might be. This isn’t really just about, obviously, gay or lesbian people. It’s about what we stand for as a country, what the military is, how we can get the best skills in that military, and that — most importantly, I think, the way we are treating people who presently have to lie about their particular sexual orientation. It’s not the way this country should operate.

AMY GOODMAN: As the former Secretary of the Army, do you have President Obama’s ear?

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER: I don’t have his ear. I’m an old friend of his. I’ve known him for many, many years. I don’t pretend to be his adviser. I have not talked to him since he’s become president. And I do think that what I understand is that he has heard this from many people. He certainly has read it in many newspapers in many editorials. And I have spoken publicly about it. I would hope and think that he’d know what my own opinion would be on it. It is something that obviously I believe he should speak out on.

I do think, however, that the initiation of something has to come from the Congress. It is not something that he personally can change. So it should be directed, yes, to a certain extent at him, but to a great extent to the broader legislative bodies and seeing to it that they don’t talk about it in terms of, “Oh, well, we’ll get to this after we fix the economy.” Let’s get to it because it’s an important issue to fix right now.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re speaking to the former Secretary of the Army, Clifford Alexander. We’re going to break, and when we come back, we’ll also be joined by Nathaniel Frank, whose book, Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America, looks at how gay men and lesbians have been treated in the military. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking about the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. Our guests are the former Secretary of the Army, Clifford Alexander; Cleve Jones stays with us, organizing a major march on Washington on October 11th — he’s visiting military bases as he organizes; and we’re joined by Nathaniel Frank. His book is Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. He’s joining us from Chicago, though he is a research fellow at the Palm Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Nathaniel Frank, how did “don’t ask, don’t tell” —- how did this policy start? And what has been the history of policy towards gay men and lesbians in the military in this country?

NATHANIEL FRANK: Well, Bill Clinton made a rather glib promise during his campaign for the presidency in 1991 and 1992, in which he said he would lift this ban by the stroke of a pen. And he had spoken to some friends and aides, including David Mixner, who continues to be a prominent gay activist, who said that this would be something that would be important to the gay community, among other issues including HIV. And Clinton underestimated the resistance that he would face among social conservatives, particularly the religious right, as well as members of the military. And so, after quite a battle with Sam Nunn in the Congress, who was very against this, and Clinton and General Colin Powell and other members of the military, the compromise was agreed to that says that you can serve if you conceal your sexual identity and remain celibate twenty-four/seven.

This came on the heels of centuries of mistreatment of homosexuals, although it was rendered in terms of sodomy, of the behavior. There wasn’t the idea of a modern homosexual identity. And so, starting with George Washington’s army, there wasn’t particular regulations targeting gay people; it was targeting sodomy, that is, gay behavior. And even then, for the first century, it was all rendered in terms of euphemisms, you know, unnatural carnal copulation. And only in World War I was sodomy mentioned. And then by World War II, it was homosexuals themselves had to be screened out of the military. And that was the case up until 1993, when we got “don’t ask, don’t tell.”

AMY GOODMAN: And what is the significance of it being passed by Congress, rather than just a policy of the Pentagon?

NATHANIEL FRANK: Well, a couple things. First of all, because it’s now a matter of federal law for the first time, because before that it was just a Pentagon policy and regulation, it’s now that much more difficult for the policy to be repealed, because as a law passed by Congress, Congress would need to repeal it.

I do want to correct one thing that Secretary Alexander said, that President Obama does have the power to stop the firings. He can act unilaterally to use his powers of stop-loss through a statute, 12305 from 1983, in which Congress itself gives the President the power to stop separations in the military for a variety of reasons. And so, he has said that he wants to stop the firings, and he actually has the power to stop the firings. And so, it’s really been very unclear to many of us why he’s unwilling to take that step. The White House has been -—

AMY GOODMAN: You mean it would be an executive order?

NATHANIEL FRANK: It would be an executive order halting all separations while we are under a national emergency, which the statute defines as being — having the National Guard mobilized, as it currently is. And then he could go to Congress some months down the line and say, “Look, we’ve had openly gay service officially” — incidentally, we already have openly gay service; thousands of people are serving openly, notwithstanding the policy. But he could turn to this situation officially and say, “We have openly gay service because of this executive order. The sky hasn’t fallen. Now, Congress, let’s move to get this off the books permanently.” So it would be a one-two punch. And that is an option that Obama has. And he’s been asked about it, the White House has been asked about it, and they haven’t given a good reason why, given what he said about wanting to stop the firings, he’s continuing to let the firings go, when he has the power to do otherwise.

AMY GOODMAN: This issue of it undermining national security, Nathaniel Frank, your subtitle, of course, contradicts that, says How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. But talk about the history of this argument.

NATHANIEL FRANK: Well, there’s a long heritage of trying to find a kind of roving rationale to justify what clearly is a gut instinct, a set of prejudices, a moral concern. I go through this in Unfriendly Fire, in the book, in great detail about the religious right seeing this as a moral issue, seeing homosexuality as sinful, and feeling that they didn’t want their military, in their words, and their government to endorse this kind of a, you know, quote/unquote, “lifestyle.” And so, there were actual conversations among members of the religious right, military evangelicals, and military members, including members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in which they decided that they would basically sell this policy to the public as a matter of national security, even though in reality what the concern was was moral, cultural and religious. So there’s a long history of this being the case.

And there’s never been any evidence, as Secretary Alexander wisely said, linking sexual orientation to having any impact on military effectiveness. It’s something that people have asserted again and again ’til it took on the resonance of truth, and it’s simply not true. The military’s own studies have again and again since the 1950s assessed this question and found that there’s no link, and they often try to bury the studies. In fact, I spoke to members of the Military Working Group, senior retired officers who were tasked with creating the blueprint that became “don’t ask, don’t tell” for the research in my book, and they told me, several of them, this policy was not based on any empirical evidence. It was not based on research. It was subjective, and it was based on our own fears and prejudices.

AMY GOODMAN: Nathaniel Frank, what about the policies of other countries and US soldiers working next to armies that have openly gay soldiers?

NATHANIEL FRANK: There are at least twenty-four, and counting, foreign militaries that include all of our major allies, including combat-tested militaries such as Britain, Israel, Australia, Canada. Even some of the smaller militaries that conservatives are fond of dismissing have actually led the way in battles in Afghanistan, in particular, in which US service members have served under them and served shoulder to shoulder in countries that allow gay service. And in the book I document actual cases where they work under known gays. This gives the lie to the idea that working amidst known gays would undermine military cohesion, as does the fact that —-

AMY GOODMAN: Give us examples.

NATHANIEL FRANK: Well, there were battles in southern Afghanistan in which the Canadians led the way to rout the Taliban and killed or captured 500 Taliban members. These were charges that were led by Canadians and British forces and the Dutch, you know, militaries that were long dismissed as having no relevance because they had no combat capabilities or no combat experience. This was before 9/11. Now things have changed. So there are very specific scenarios.

And I would also add that every time that we go to war, throughout history, throughout the twentieth century and counting, discharges for homosexuality plummet. They have fallen in half since 9/11. And the reason is because even the military doesn’t believe that homosexuality undermines unit cohesion, because during wartime, when cohesion and effectiveness are most essential, commanders look the other way, because they know that gay people are just as capable and just as needed in these military campaigns as anyone else.

AMY GOODMAN: The linguists who were fired after 9/11, when the US was desperately in need of linguists, fired because they were gay, Nathaniel?

NATHANIEL FRANK: That’s right. The day before 9/11, on September 10, 2001, a cable was intercepted by the government that said, “Tomorrow is zero hour.” It wasn’t translated until two days later, a day too late. And one of the reasons is that we had a dire shortage of Arabic linguists. And we’ve kicked out over sixty Arabic linguists, 300 linguists in total. Sixty of them have been Arabic linguists.

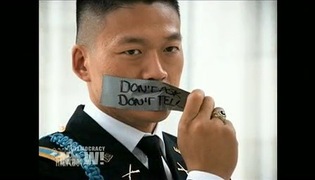

And we have had dire warnings by every government agency and Congress saying we need more Arabic speakers. We need people who can translate what the people who want to hurt Americans are saying, as well as translate what people who we’re trying to win over in the population in the Arab countries where we’re fighting. And both of those rely absolutely on the critical specialists, of Arabic linguists like Lieutenant Dan Choi, a West Point graduate and combat veteran, who has been told he will be discharged under the Obama administration. He’s fighting it. And he’s just one among many.

Every last person in the military is a valued contributor to those missions. And these critical specialists, the idea that they’re just dispensable because of something that has no bearing on military capability, it’s a very unwise way of crafting public policy and national security policy. It’s illogical.

AMY GOODMAN: Cleve Jones, as you organize for the October 11th march in Washington, you’re organizing on military bases. Talk about the people you meet and their rights or lack of rights.

CLEVE JONES: I’ve visited with military personnel from a number of bases in California and Hawaii. And, you know, it’s very poignant. You meet these brave young men and women who are putting their lives on the line. Some of the young people I met were getting ready for their third tour of duty in Iraq or Afghanistan. And it’s so hypocritical. And many of them are in this sort of odd limbo, where they are really out. You know, the other members, the people they work with, their colleagues, know that they’re gay. Their commanding officers know that they’re gay. They’re turning a blind eye to it.

I was particularly struck during a visit to Honolulu, where in a town hall meeting a young sailor spoke about his partner and his fear that he would lose his life in combat and that there would be no survivor benefits for his partner. So I think it’s an incredibly cruel policy. It’s foolish. It makes no sense whatsoever. And I’m glad that there’s this much focus on this. I’m working closely with Lieutenant Choi on this march organizing process, and he’s a really inspiring young man. I think any parent would be proud to claim him, and I think any country should be eager to honor him and his service.

AMY GOODMAN: Clifford Alexander, is there organizing -— are you involved in organizing in the leadership of the military, past and present, to take on this policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell” that has led to, what, the firings of something like 13,000 service members since it was put in place?

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER: I would emphasize to you — yes, I’ve been on some lists of groups that have wanted to eliminate this policy for some time. But it is extraordinarily important, I think, to understand that you don’t take a poll of generals to decide whether it’s a policy or not a policy. We have something in our country called civilian control. So those who are in the executive branch and the legislative branch have control over this policy. And it should not be determined by, I saw the other day, a group of flag officers who thought this was a bad policy, with no evidence, because there isn’t any evidence. It is up to, in the kind of society we have, civilians to set this policy and to see to it that it is changed. I think that it requires the kind of heated light that I think is being placed on this issue at the present time. And the more of that from as many sources as possible, I think the better. But I don’t think that we need to take a poll of the military. I don’t think we need to study it anymore. We need to urgently speak out and do whatever we can.

AMY GOODMAN: Nathaniel, talk about how someone is fired.

CLIFFORD ALEXANDER: When it comes to the attention of a commander that someone may have engaged in homosexual conduct, which is, in a sense, a euphemism for being gay, because it’s cast as though this is only focusing on behavior and whether you’ve done something wrong, but in fact, if you simply say you’re gay, or worse, if an email is read, if a letter is read, if your phone calls are tapped, if a third party calls and basically tells on you, then you are considered to be in violation of the homosexual conduct policy, even though you haven’t engaged in any conduct. And so, if the commander deems it to be credible evidence, the commander will either investigate by launching an investigation or sending a letter saying, you know, “It’s come to our attention that you have engaged in prohibited conduct.” And you can decide to either go before a board and present evidence that you don’t have a propensity to engage in homosexual conduct, which is sort of the bar, or you can decide to go willingly, which some people do because they’re concerned that they might, in an investigation, dredge up some information that would cause the discharge to be dishonorable, whereas in most cases it’s an honorable discharge.

I do think what Cleve Jones mentioned about the harrowing experiences of the estimated 65,000 service members who are currently in uniform really shouldn’t be lost. And it’s, you know — yes, it’s things like benefits. It’s also the idea that your partner could lose his or her life, and you would never be notified, and that you can’t be in touch with people and that the service members themselves aren’t involved in the best readiness for going to combat, because they can’t put their paperwork in order. I’ve spoken to people who had to change the name Brian to Briane by adding an “e” so that they could chalk up the difference to a legal error if they needed to claim the paperwork, but that they would be hiding the gender of their partner.

So — and one final matter about the generals. There is this list of a thousand generals that have said, again, as Secretary Alexander said, with no new evidence, no research, they have simply expressed their anti-gay sentiment. Many of them, most of them, didn’t serve under “don’t ask, don’t tell.” They are from a different world. They served many, many, many years ago. And this is a religious right tool that organized this to simply express the homophobia of years past.

Today, General John Shalikashvili has an op-ed in the Washington Post, a former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. And both Colin Powell’s predecessor and successor in that position have now called, looking at all the evidence, for a repeal and an end to “don’t ask, don’t tell.” And Shalikashvili writes that in today’s Washington Post. So there is some debate among military people. And I think that’s appropriate.

AMY GOODMAN: Nathaniel Frank, what should the policy be?

NATHANIEL FRANK: It should be a policy of nondiscrimination, which is what the Military Readiness Enhancement Act that’s currently pending in Congress says. It would repeal the current policy that requires discharge for conduct, and it requires that you not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. It’s quite simple.

AMY GOODMAN: On this day that we lead into Father’s Day, I wanted to go back to your daughter, Secretary Alexander. I wanted to turn to a portion of the poem that she read. Poet Elizabeth Alexander, she read her poem at Barack Obama’s presidential inauguration. She called it “Praise Song for the Day.”

ELIZABETH ALEXANDER: Some live by love thy neighbor as thyself,

others by first do no harm or take no more

than you need. What if the mightiest word is love?

Love beyond marital, filial, national,

love that casts a widening pool of light.

AMY GOODMAN: And with that, we end today’s broadcast. That was Elizabeth Alexander reading her poem at the inauguration of President Barack Obama. That does it for our show. I want to thank Cleve Jones, organizing the October 11th march on Washington on October 11th. I want to thank Nathaniel Frank, joining us from Chicago, Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America. And the former Secretary of the Army under President Carter, Clifford Alexander, the first African American Secretary of the Army, as well, speaking out against the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

Media Options