Guests

- Clayborne Carsonhistorian and professor of history at Stanford University. He is the founding director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.

President Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, along with hundreds of mourners, packed into the National Cathedral in Washington, DC on Thursday to attend the funeral of civil rights and women’s rights leader Dorothy Height. She died last week at the age of ninety-eight. We speak with Stanford University professor Clayborne Carson. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, along with thousands of mourners, packed into the National Cathedral in Washington, DC Thursday to attend the funeral of civil rights and women’s rights leader Dorothy Height. She died last week to the age of ninety-eight.

Dorothy Height served as president of the National Council of Negro Women for forty years, where she fought for equal rights for both African Americans and women. During the 1960s, she organized Wednesdays in Mississippi, which brought together black and white women from the North and South to create a dialog of understanding. She worked closely with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and many other prominent civil rights activists. In 1971, she helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus. And in the last months of her life, she took part in healthcare discussions at the White House.

At the funeral service on Thursday, Camille Cosby and poet Maya Angelou were among those who paid tribute to Dorothy Height. President Obama weeped during the service before taking to the podium to deliver a thirteen-minute eulogy. He hailed her achievements and ended by recounting one of his favorite stories about Dorothy Height.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: One of my favorite moments with Dr. Height, this is just a few months ago. We had decided to put up the Emancipation Proclamation in the Oval Office, and we invited some elders to share reflections of the movement. And she came. And it was an inter-generational event, so we had young children there as well as elders, and the elders were asked to share stories.

And she talked about attending a dinner in the 1940s at the home of Dr. Benjamin Mays, then president of Morehouse College. And seated at the table that evening was a fifteen-year-old student, a gifted child, as she described him, filled with a sense of purpose, who was trying to decide whether to enter medicine or law or the ministry. And many years later, after that gifted child had become a gifted preacher — I’m sure he had been told to be on his best behavior — after he led a bus boycott in Montgomery and inspired a nation with his dreams, he delivered a sermon on what he called the “drum major instinct,” a sermon that said we all have the desire to be first, we all want to be at the front of the line. The great test of life, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, is to harness that instinct, to redirect it towards advancing the greater good, towards changing a community and a country for the better, toward doing the Lord’s work.

I sometimes think Dr. King must have had Dorothy Height in mind when he gave that speech, for Dorothy Height met the test. Dorothy Height embodied that instinct. Dorothy Height was a drum major for justice, a drum major for equality, a drum major for freedom, a drum major for service. And the lesson she would want us to leave with today, the lesson she lived out each and every day, is that we can all be first in service, we can all be drum majors for a righteous cause. So let us live out that lesson. Let us honor her life by changing this country for the better, as long as we are blessed to live. May God bless Dr. Dorothy Height and the union that she made more perfect.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama delivering the eulogy at the funeral service for Dorothy Height yesterday. Obama ordered flags to be flown at half-staff on Thursday in Height’s honor.

Before we look at her life and legacy, we go back to Dorothy Height in her own words. In 2005, she spoke before a massive crowd assembled on the National Mall in Washington, DC for the Millions More March.

DOROTHY HEIGHT: I say, anyway, that African American women are very special women, because we’re women who seldom do what we want to do but always do what we have to do. And we know how to take care of ourselves, our families and our communities. And I was here ten years ago, and I feel blessed that I have the opportunity to be here now. Then, we had the Million Man March, and that was a great day, because it was so uplifting, and it gave us all a new determination to do what we could to help build our families and communities. And now we are here, and we are here from all over the country, from many different backgrounds. And I think one of the things that we have learned is that we may have come to this country by different ships, but we’re all in the same boat now, and that we have to learn how we work together. And in the civil rights movement, we learned that unity did not mean the same, or that uniformity, but that whatever our differences, we learned to get focus.

AMY GOODMAN: Dorothy Height, speaking at the Millions More March on Washington, DC in 2005. When we come back from break, we’ll be joined by Stanford University professor Clayborne Carson, historian and professor of history here. Stay with us.

[break]

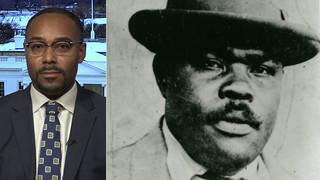

AMY GOODMAN: In this segment, we remember Dorothy Height, the funeral for her held at the National Cathedral yesterday in Washington, DC. But we’re at Stanford University in California, on the road, and are joined by Clayborne Carson, professor of history here at Stanford University, the founding director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute. He met Dorothy Height a number of times.

We welcome you to Democracy Now!.

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Good to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about her legacy? She was ninety-eight years old when she died.

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Well, she went through an era where most of the landmark civil rights reforms took place, but also where there was a transition of leadership within the black community, and she became much more prominent as the women’s movement took shape during the late 1960s. And you begin to see her really flowering, actually, late in her life.

My memory of her, last memory, was at a panel discussion, and I remember she came in on a — she was in a wheelchair, and she looked very frail, and she took her place on the panel. But as soon as she started speaking, that life, that spirit, came alive, and you began to see that even though she was in her nineties, she was still fighting the good fight.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re the chief archivist for Dr. King’s works, in addition to being a historian. Can you talk about her relationship with Dr. King?

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Well, she knew the family. I mean, she had a long connection, as she had been very active even in the '40s and ’50s. And so, she had that familiarity. She had met Martin Luther King during the 1950s. And, of course, later on, she was in — their paths crossed, most notably, at the March on Washington, even though she was not invited to speak at the march.

AMY GOODMAN: In 1963.

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: In 1963. But they certainly knew each other. She was part of what was called the Big Six of black leaders and that often went to the White House to talk with presidents about civil rights reform.

AMY GOODMAN: The organization that she headed for so many years, its significance?

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Well, it had been started by Mary McLeod Bethune back in the 1930s, because she felt that black women had to have a voice in national discussions of policy.

AMY GOODMAN: And who was Mary McLeod Bethune?

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Well, Mary McLeod Bethune, unfortunately she's not that well known these days, but she was once the most politically influential African American leader of her time. She was in Roosevelt’s New Deal administration, and she had the ear of President Roosevelt. So she was able to shape a lot of New Deal policy to help combat discrimination in the implementation of New Deal programs. So from probably in the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s, she was the person that everyone had to go through to get to Roosevelt.

AMY GOODMAN: And the role of the National Council of Negro Women over the decades, when Dorothy Height was at its helm?

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Well, it’s an umbrella organization. It brings together practically every major national black women’s group, I think representing some millions of black women. So, what Bethune had in mind was that there needed to be a single voice kind of representing all of these constituencies when discussions of national policy — you know, for example, during the New Deal, there was a special need for black women to be heard, because domestic servants were not included in many of the initial New Deal legislation, like Social Security, for example. So, as we got toward the era of civil rights reform, there still needed to be someone speaking for the special needs of black women.

AMY GOODMAN: She was the recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, accorded a place of honor on the dais at the inauguration of President Obama. I’m looking at a New York Times piece that talks about historians making much of the so-called Big Six who led the civil rights movement — Dr. King, James Farmer, John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young.

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Actually, she was not formally a member of the Big Six.

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: She was often included in the discussions, but that was one of the reasons why she was not included as a speaker at the March on Washington, even though she was there and recognized.

AMY GOODMAN: What about her being the unheralded seventh, as they say? I mean, of not speaking. What were her views on that?

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Well, she became increasingly disturbed by it. I think that for many women who were involved in the movement at a very high level, certainly as activists, someone like a Diane Nash, or as an organizer, someone like a Dorothy Cotton, you know, the fact that they were playing important roles in the movement, and yet, when it came to the March on Washington, all the main speakers were men. And they had a — even they had a section of the March on Washington — I was there, and I remember that they brought forward, I think they called them, “heroines of the movement,” and for a presentation, but with no voice.

AMY GOODMAN: And President Obama’s relationship with her? I think she went to the White House twenty-one times.

DR. CLAYBORNE CARSON: Yes, that was a very — apparently a very special relationship. And I think he recognized that she was a very special voice. And she represented a generation of black leaders who had, really, I think, the greatest generation. You know, we talk a lot about the World War II soldiers, but for me, the great generation was the ones who were part of this great freedom struggle all around the world that brought citizenship rights to the world’s majority. And she was part of that generation. And there’s not — you know, that generation is now passing on. But they played this historic role of, in the United States, of course, leading this long struggle for civil rights reform to its culmination. But I think she understood that this was not just in the United States, this was something going on around the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much for being with us, Clayborne Carson, professor of history here at Stanford University. He’s the founding director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.

Media Options