Related

Topics

Guests

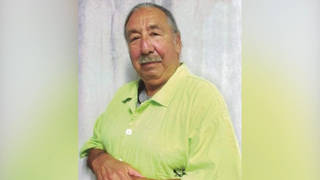

- Horace Campbellprofessor of political science and African American studies at Syracuse University.

- Gnaka LagokeIvory Coast political analyst. He runs the website AfricanDiplomacy.com.

Ivory Coast’s political crisis remains in a deadlock following a day of talks with visiting African heads of state. On Monday, a delegation of leaders from Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Cape Verde and Kenya met with both Ivory Coast President Laurent Gbagbo and longtime opposition leader Alassane Ouattara. Gbagbo and Ouattara have each claimed victory in November’s disputed election. Ouattara has received the backing of the international community. We speak with Horace Campbell of Syracuse University and Gnaka Lagoke, an Ivory Coast political analyst. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to Côte d’Ivoire — in English, the Ivory Coast — whose political situation remains in a deadlock following a day of talks with visiting African heads of state. On Monday, a delegation of leaders from Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Cape Verde and Kenya met with both Ivory Coast President Laurent Gbagbo and longtime opposition leader Alassane Ouattara. Gbagbo and Ouattara have each claimed victory in November’s disputed election. Ouattara has received the backing of the international community, including the Economic Community of West African States, known as ECOWAS, which has threatened military action if Gbagbo does not agree to step aside.

Gbagbo’s security forces have been accused of orchestrating some 200 deaths, hundreds of arrests, dozens of cases of disappearance and torture in recent weeks. Last week, Ouattara’s appointee to the United Nations warned the standoff has placed Ivory Coast “on the brink of genocide.”

There are conflicting reports today on whether Gbagbo and Ouattara will meet face to face. Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga says the two have agreed to hold talks, but Ouattara’s camp quickly denied the claim. On his way to the airport, Sierra Leone President Ernest Bai Koroma said only that the talks will continue.

PRESIDENT ERNEST BAI KOROMA: We have had very, very important meetings, following a mission from ECOWAS and the A.U. At this stage, I can only say that the discussions are ongoing.

AMY GOODMAN: The meetings came just one day after President Gbagbo appeared on national television and accused Ouattara of staging a coup and backing foreign military action.

PRESIDENT LAURENT GBAGBO: [translated] Let’s not kid ourselves. Let’s not let ourselves be abused by words. It’s about an attempted coup d’état brought in under the banner of “international community.” This action is destined to bring in, by force if they need to, as the leader of this country a man who Ivorians didn’t choose by their votes — as my rival has lost in the presidential elections from November 28, 2010.

AMY GOODMAN: For more on Côte d’Ivoire, Ivory Coast, we’re joined by two guests. Horace Campbell joins us again, professor of political science and African American studies at Syracuse University. His latest book, Barack Obama and 21st Century Politics: A Revolutionary Moment in the USA. Horace Campbell is joining us today from Syracuse. And joining us from Washington, D.C. is Gnaka Lagoke. He is an Ivory Coast political analyst and runs the website AfricanDiplomacy.com.

Why don’t we begin in Washington, D.C. Talk about the latest, the situation that is taking place right now in the Ivory Coast. President Gbagbo says that the election has been rigged. What is your sense of this?

GNAKA LAGOKE: Thanks, Amy. I think it’s a very complicated question, because both sides say that elections — Alassane Ouattara is recognized by international community. And many people close to the president think that if people do the recount, people will find out that there were many electoral protests in the north and that Gbagbo Laurent will be seen as the true winner of the election.

I, myself, have seen some conflicting numbers. You know, when I was trying to follow the election after the runoff, I have seen a result coming from the United Nations mission in the Ivory Coast and result coming from other sources. I have seen that, for instance, the number of registers on some electoral list in some parts of the Ivory Coast, the first round and the second round did not match. I have seen that myself. But I cannot say, when — as I speak, that I have seen all the numbers that Gbagbo has truly won the election or Alassane Ouattara has truly won the election. This is what I can say to answer your first question.

AMY GOODMAN: And who are they both? Who is President Gbagbo? Who is the opposition leader Alassane Ouattara?

GNAKA LAGOKE: OK, yeah. Laurent Gbagbo is a freedom fighter. He struggled for 30 years, you know, to bring democracy and freedom in the Ivory Coast. He was the main opposition leader to Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who was a benevolent dictator who ruled the country for 33 years.

And Alassane Dramane Ouattara has a different path. He’s obviously a banker, an economist, who got his Ph.D. at age 30 here in the U.S. And then, you know, when he became the prime minister of the Ivory Coast in 1990, and I think he was discovered that he could give it a try, you know, to run for president, when he noticed that many people from the north thought that, you know, they could go through him, you know, to access to state power.

So, both — one is a professional politician, Laurent Gbagbo. One is an economist. And both of them are competing and fighting for almost 20 years in the political arena. And both also symbolize the division of the country between the south and the north. And both have different ideologies about governance. Gbagbo Laurent is a socialist. Alassane Ouattara is a liberal, obviously believes in neoclassical economy, and because when he was the prime minister of the Ivory Coast, he was implementing many policies like proposed by the IMF. So, this is, I think, if I can give you a brief description of both people.

AMY GOODMAN: And how dire is the situation right now with ECOWAS threatening to engage in military action to force Gbagbo out?

GNAKA LAGOKE: Yeah. When I got an opportunity to talk about that on — like, on other shows, I oppose a military intervention in the Ivory Coast, and I think that that was not a good intention, that was not a good decision. People might still come to — might still go to Ivory Coast, you know, to try and take Gbagbo out of power using military intervention, but I think it is a very bad idea, because everybody knows that the seeds of turmoil in our people, you know, that brought Ivory Coast on the brink of a civil war are in every African country, and particularly in Nigeria. And everybody knows that in less than four months Nigerians are going to go to vote. And everybody knows that and the reports support that Jonathan Goodluck is going to try and put an end to the zoning system according to which the north and the south in Nigeria alternate power every eight years.

Now, Ivory Coast is a microcosm of a united Africa. Twenty-six percent of the population in Ivory Coast come from foreign countries. If you find — if you look at a family in the Ivory Coast, you will see that one parent comes from — how can I say? — from a traditional ethnic group in the Ivory Coast, and the other parent comes from a foreign country. So when you attack Ivory Coast, you’re not just trying to destroy or kill people from Gbagbo’s tribe, but you’re trying to destroy a microcosm of the united Africa. And that’s why I opposed a military intervention in Ivory Coast yesterday, and I oppose a military intervention in Ivory Coast today, and I will oppose a military intervention in Ivory Coast tomorrow.

AMY GOODMAN: Horace Campbell, you’re a professor at Syracuse University. You have been looking at Africa for many decades. What is your position on what’s happening right now in the Ivory Coast?

HORACE CAMPBELL: Well, good morning, Amy. And good morning, my brother.

GNAKA LAGOKE: Good morning.

HORACE CAMPBELL: I think that the discussion is very pertinent to the new challenges for the African peoples, that we must have a higher standard for what is called democracy and people’s rights and peace. And I was very, very intrigued by the fact that my brother said that Gbagbo was a freedom fighter for 30 years. But all over Africa, we have the experience of freedom fighters who come to power, whether they’re in Uganda — Museveni — or in Zimbabwe — Mugabe — or in Eritrea or in Ethiopia. When these freedom fighters come to power, they turn the society into militarized society and use the old discourse of politics of anti-imperialism to maintain themselves in power.

Now, I agree that the question of the Ivory Coast is not about Gbagbo and about Ouattara. The question of democracy in the Ivory Coast is whether all citizens of the Ivory Coast will have the right to participate in the political system. And what is at stake here is the long challenge that people from the north who are considered from Islamic background, whose parents migrated to the Ivory Coast, whether they can participate in the political process and become leaders of the country. Your guest is very right about the ideological and political orientation of Alassane Ouattara, but what that also is hiding is a question of the Islamic question that is in the country, where there are some people from the south that says another northerner cannot become a leader. And that is why, for the past 15 years, there was a struggle in the Ivory Coast over this idea called Ivorité. And Ivorité is simply a shield for xenophobia and the kind of chauvinism that should be opposed by pan-Africanists, by peace-loving persons.

And I agree with your guest that military intervention should be the last resort, but there should be other forms of intervention — diplomatic, financial, even information — so that Gbagbo does not manipulate the position of power to enrich himself and enrich his friends who are using the resources of Ivory Coast to maintain themselves in power.

One of the things we want to stress here is that democracy is not simply about voting in elections. The Gbagbo forces, who were freedom fighters, need to explain to the people of Africa how is it that they made an agreement with Trafigura and Marc Rich to dump toxic waste in the Ivory Coast. So, the democracy is much more [than] about elections and bringing Ouattara to power. And part of the lessons we should learn out of this long process to democratize the Ivory Coast, that is much more than Ouattara and Gbagbo, it’s about democratic rights for the working people, democratic rights for those who work on cocoa plantation, the rights of women, the rights of people of different religious and different ideological orientations.

AMY GOODMAN: But Professor Campbell, the issue of ECOWAS military intervention, where do you stand?

HORACE CAMPBELL: Well, the issue of ECOWAS military intervention is a threat which is being used to present to the government of the Ivory Coast — that is, the illegal government of Gbagbo — that the African society and African peoples will not tolerate illegal hold of power. This is part of the Constitutive Act of the African Union. It is my view that military intervention should be the last resort, that there should be all forms of negotiations and discussions. And the discussions and sanctions should be the ones that are used to bring down the Gbagbo regime. It is my view also that for four or five months, Gbagbo will not be able to pay the military, that is the backbone of his power, and that the ECOWAS position is a united position of the African Union. And this is only, I hope, a threat, because I agree with your guest that military intervention would complicate the whole region, becaus there is no society in West Africa that would escape the conflagration of the war. So I do not believe that we should have militarism to bring about democracy in Africa. So, yes, I would hope that military intervention is not what is used to bring about change in the government in the Ivory Coast.

AMY GOODMAN: And how is it known, Horace Campbell, that Gbagbo actually lost the election, the current president?

HORACE CAMPBELL: How is it known that Gbagbo lost the election?

AMY GOODMAN: Why is it believed that he actually lost the election?

HORACE CAMPBELL: Well, it is believed that Gbagbo lost the election because all of the observers and all the information from the African Union, from ECOWAS, from African civil society organizations and the United Nations certified that the election results that Gbagbo lost the election. The only source that says that Gbagbo did not lose the election is Gbagbo himself —

AMY GOODMAN: Gnaka —

HORACE CAMPBELL: — and those spokespersons for Gbagbo outside of the Ivory Coast.

GNAKA LAGOKE: Hello?

AMY GOODMAN: Gnaka Lagoke, you wanted to respond.

GNAKA LAGOKE: Yeah, thank you very much, Amy. Yes, Campbell, I know — well, I’ve read the interview you had with Amy, you know, when I was coming to the show, and I’ve seen that, you know, you are very knowledgeable about politics in the world, and particularly like in Africa, but there are a few facts, you know, I think, like, you are misreporting.

Ivorité is — was like a concept that was conceived by Henri Konan Bédié. Gbagbo Laurent was accused of surfing on that concept when he came to power, but the reality is this. In 1990, there was also an ideology on behalf of the people who live in the northern part of the Ivory Coast, and that ideology is called the chart of the northerners. If you get a chance to read the book, Côte d’Ivoire–L’Année Terrible 1999-2000, page 301, you will see the document published in that book. You cannot — when people talk about the northerners in the Ivory Coast, yes, there were some abuses, and even many abuses, against them, the same way the state of the Ivory Coast did abuse some of the citizens in the south, the people coming from Gbagbo’s tribe, people coming from the eastern part of the Ivory Coast. So, because, like I said, Houphouët-Boigny was in power for 33 years and he was succeeded by Henri Konan Bédié, who did not change too much, you know, the policies or the policies of the state towards some citizens in the Ivory Coast. So, yes, Ivorité is a divisive concept. There was also the chart of the northerners.

And Alassane Dramane Ouattara, when he was the prime minister of the Ivory Coast, you can see those videos on YouTube, when he was interviewed about that separatist movement of the chart of the northerners, he did not do anything, you know, to distance himself from that concept and that ideology. And then, many believe in the Ivory Coast and, like, even in Africa, that he has also used ethnicity to his advantage.

So now, I am a pan-Africanist, and I believe that if Alassane Ouattara is the winner and is truly the winner of the Ivory Coast, that he should have the right to be the president of the Ivory Coast. But it is a disputed election. And then, when you say that everybody says that Alassane Ouattara won the election, yes, the United Nations and many other observers, but you still have other voices that are not reported in the international media, like there were the African observers. I’m not here to defend Gbagbo’s case; this is not what I’m doing. Gbagbo was a freedom fighter when he was in the opposition and he came to power. He might have miscalculated the power of corporate governance or the power of the imperialism, you know, to try and overthrow him. But when you talk about people in the north who are the victims of everything that is going on in the Ivory Coast, I think that it is too much, and I think that you should put that into context. And this is — things don’t happen — things did not happen like that in the country.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Campbell?

GNAKA LAGOKE: Alassane Ouattara was banned — Alassane Ouattara was banned from the election, because even though he was born in the Ivory Coast, for more than like 20 years he was known as a citizen of Upper Volta. And then when he came to Ivory Coast, even though Ivory Coast is the land of immigrants, there were people — and it was alleged to be the fear from people in the south, who believe that Alassane Ouattara is going to represent like foreign interests who are coming to come and take over the Ivory Coast.

And I’m not saying, I — I agree that he run for president, but at the same time, like Rawlings said, the president of Ghana — and that was my last statement on this question — that the situation in the Ivory Coast goes beyond an electoral dispute. It is a “web” — and I’m quoting Rawlings — it is a “web of ethnic and political complexities” that need to be handled with diplomacy. So, it’s not just about election. Gbagbo was in power. Alassane Ouattara funded the rebellion to come and overthrow him. So, people in Gbagbo’s camp think that it is injustice done to their leader, that the same way — even if Gbagbo has lost, they think that they should continue doing what they’re doing. So, that’s why the situation in Ivory Coast is very complicated.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Campbell, a very quick response and then the significant resignation of Lanny Davis, the corporate lobbyist in Washington, D.C., who was the special counsel to President Clinton when Clinton was president, resigning from or no longer representing President Gbagbo of the Ivory Coast, after he came under enormous criticism. Among those critics were you on Democracy Now! last week.

HORACE CAMPBELL: Well, Lanny Davis stepped down because it was embarrassing. And the information about Gbagbo and his violation of the rights of the peoples of the Côte d’Ivoire are well known. And because Gbagbo is now known as a former freedom fighter who is holding onto power, Lanny Davis is correct and is correct to step down. And it is the work of those in the peace movement, those in the progressive wing of the pan-African movement, to stress what are the questions for the people of Côte d’Ivoire and the people of West Africa. The most important questions are the quality of the life of the people of West Africa, peace, reconstruction, health and the web of people’s rights. I do not agree with Jerry Rawlings that this is a web of ethnic politics in the Ivory Coast. This is a web of whether one is able to be a citizen of Côte d’Ivoire regardless of whether their parents or grandparents came from Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Liberia, because all over Africa, we have these questions of citizenship. This is much more similar to the situation in Kenya, where the ruling party held onto power in 2007, 2008, saying someone who’s a Luo from northern Kenya cannot become a president of Kenya.

Now, I agree completely with your guest that Alassane Ouattara represents neoliberalism in the Côte d’Ivoire. And it is our task in the peace movement to ensure that the struggle against Gbagbo focuses not only on Ouattara, but on citizenship rights, the rights of women, the rights of youth, the right to demilitarize the situation. And this way, I agree with your guest. The challenge is, how can we set up sanctions, information levers and other measures to force the people of Ivory Coast to intervene politically so that this kind of chauvinism and xenophobia, which is exhibited in Ivorité, is banned from African politics, because we see it all over Africa? We see it where the politicization of ethnicity, the politicization of religion, the politicization of region. These are not the central political questions in Africa. The central political questions in Africa are life, health and the quality of the well-being of the youth. Your guest did not say that for the past 10 years, since 2000, Gbagbo has been in power. While he’s been in power, this same clique that holds onto power, I will repeat, got paid so that toxic waste could be dumped in the Ivory Coast, and hundreds of people died in — and I’d say the quality of life, environmental justice, these are the questions for peace and democracy, not just voting in elections.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to leave it there, and I thank you both for being with us. Gnaka Lagoke, a Ivory Coast political analyst, speaking to us from Washington, D.C., his website is AfricanDiplomacy.com. And Horace Campbell, professor of political science and African studies — African American studies at Syracuse University. Professor Campbell, if you could stay with us, after break, we’re going to talk very briefly about Sudan and the upcoming referendum.

Media Options