Guests

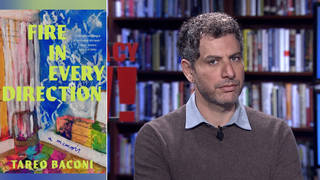

- Patricio Naviain Santiago, Chilean political scientist. He teaches at the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University and at the Universidad Diego Portales in Santiago. Navia writes regularly for the Chilean newspaper, La Tercera.

In Chile, tens of thousands of students have been protesting across the country for the last several weeks demanding comprehensive educational reforms. Students have expressed frustration at President Sebastián Piñera’s failure to respond to their demands. Last week, high school students in the port city of Antofagasta joined a hunger strike by students called earlier in the capital, Santiago. They are demanding an end to privatized education in Chile, which has left generations of students deep in debt. We speak with Chilean political scientist Patricio Navia in Santiago. He teaches at the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at New York University and at the Universidad Diego Portales in Santiago. He writes regularly for the Chilean newspaper, La Tercera. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to Chile, where tens of thousands of students have been protesting across the country for the last several weeks demanding comprehensive educational reforms. Students have expressed frustration at President Sebastián Piñera’s failure to respond to their demands. Last week, high school students in the port city of Antofagasta joined a hunger strike by students called earlier in the capital, Santiago. They’re demanding an end to privatized education in Chile, which has left generations of students deeply in debt.

SEBASTIÁN VARELA: [translated] We hope they can achieve important changes for education in Chile. What we have done, given our limited resources and in solidarity with students who started the hunger strike nine days ago, we decided to join a radicalized movement in the form of a hunger strike.

AMY GOODMAN: For more on what’s happening in Chile, we go to the capital, to Santiago, to talk to Chilean political scientist Patricio Navia. He teaches at the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies here in New York at New York University and at the Universidad Diego Portales in Santiago. He writes regularly for the Chilean newspaper La Tercera.

Welcome to Democracy Now! Explain what’s happening and how significant it is in Chile right now, Patricio Navia.

PATRICIO NAVIA: Well, this is very important. I mean, what we are seeing in Chile is that since democracy was restored in 1990, average of education increased dramatically. It is now universal for elementary and secondary education, and about 40 percent of college-age students are now—or college-age people are attending universities or private institutions. What they are demanding is that the government provides them with a better quality of education and also with student loans and other mechanisms, so that they can pay for their education without getting into too much debt.

AMY GOODMAN: And the whole issue of privatization of education in Chile, how does it fit into the general picture there?

PATRICIO NAVIA: Well, about half of the students in Chile in elementary and secondary education attend voucher schools. These are schools where the government gives a voucher to private operators for every child that goes to those schools. However, there is also a copayment, which means that different parents send kids to different schools according to how much money they make. And that has simply reproduced the very high inequalities that exist in Chile. This system was adopted during the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship in the 1980s, and it was kept, maintained during the 1990s, when democracy was restored, precisely because it allowed to expand the coverage. The quality of education kids get depends on copayment more than on the voucher.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Patricio Navia, a Chilean political scientist who teaches at the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at NYU in New York and teaches in Santiago, Chile, where he is right now, joining us by Democracy Now! video stream, as we try to perfect that stream so you can hear him more clearly. How students, their power base in Chile—I mean, it seems that the streets of Santiago in many areas are taken over by these protests. What is the response of the general population, Patricio?

PATRICIO NAVIA: Well, the response of the general population, in general, is very [inaudible]. Students, in fact, are able to take to the streets, precisely because there are so many of them. Forty percent of all the kids aged 18 to 25 in Santiago are attending some kind of higher education institution. So they have a lot of time, and they have a lot of muscle. The population is, in general, their relatives, in many instances. In fact, about 70 percent of all the students are first-generation college students. So, they represent the dream, if you will, the Chilean dream, the dream of moving up on the social ladder. And what they are demanding is that they get a [inaudible] quality education so that they can in fact move up in the ladder, and that they also get some support from the government so that they don’t end up owing about three times what they are going to make on an annual basis. Getting a college education here is somewhat the equivalent for many families of buying a house. So, students don’t want to end up heavily indebted after they get their college education or their technical education.

AMY GOODMAN: The heavy response of the state, as we look at videos of the riot police with the water cannons, and the protests that are being planned for later today?

PATRICIO NAVIA: Yes. Well, since democracy was restored in Chile, the police has always responded very heavily to protest, students or otherwise. The water cannons are sort of a trademark of police operations in Chile. Somehow, the democratic governments that took office in 1990 have not eliminated that. In order to march, they are doing it on public avenues, on the main streets, where cars go by. They have to get the special permission. The government normally has authorized students to march, but this time around the government said, “Well, no, this is the time [inaudible] down and negotiate,” and thus it did not authorize the students to march. The students are planning to march anyway at 11:00 a.m. If more than 100,000 students show up, it’s going to be very difficult for the government to prevent them from marching, because they are simply not going to have enough manpower to stop the students from taking on the main street in Santiago.

AMY GOODMAN: Patricio Navia, I want to thank you for being with us, Chilean political scientist, speaking to us from Santiago, Chile.

Media Options