Greece continues to face political turmoil over a sovereign debt crisis that has embroiled the country for almost two years. On Monday, the Greek government said it would hold new elections in the face of massive demonstrations against a new austerity package that was approved on Sunday in exchange for a European Union-International Monetary Fund bailout. Under the austerity deal, Greece will fire 15,000 public sector workers this year and 150,000 by 2015. The minimum wage will be reduced by 22 percent, and pension plans will be be cut. As lawmakers voted, 100,000 people protested outside the Parliament building in Athens. Some protesters engaged in rioting, looting and setting fire to dozens of stores and buildings. Some 160 people were detained, and dozens were treated for injuries. To discuss the latest in Greece, we’re joined by Maria Margaronis, London correspondent for The Nation magazine. She was in Greece last week covering the economic crisis there. Margaronis says Greece faces an “impossible choice” “either to default on its loans by March, when it owes a massive loan payment, or to accept this desperate austerity program, which will further sink the economy… The Greek people have really had enough of this. People are exhausted and desperate. On the street in Athens, there’s a sense of everything breaking down.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Greece continues to face political turmoil over a sovereign debt crisis that’s embroiled the country for almost two years. On Monday, the Greek government said it would hold new elections in the face of massive demonstrations against a new austerity package that was approved Sunday in exchange for a European Union-International Monetary Fund bailout.

Under the austerity deal, Greece will fire 15,000—or one in five—public sector employees, reduce the minimum wage by 22 percent, and cut pension plans. Greek union leader Vassilis Korkidis condemned the austerity deal

VASSILIS KORKIDIS: The new austerity measures were voted yesterday from the Greek parliament, but this is only temporary. We think that the Greek economy may, for the time being, be safe. We don’t know for how long. We believe that in six months we’ll be in the same position. And the only thing that we are sure is that the Greek society is poorer, and the Greek political system is bankrupt.

AMY GOODMAN: As lawmakers voted, 100,000 Greeks protested outside the Parliament building in Athens. Some protesters engaged in rioting, looting and setting fire to dozens of stores and buildings. Over 160 people were detained. Dozens were treated for injuries.

The Greek vote paves the way for the European Union and the International Monetary Fund to hand over $72 billion in rescue loans. But following the protests and ahead of a key meeting in Brussels Wednesday, European officials suggested the bailout could be delayed until early next month, adding further uncertainty to an already volatile situation.

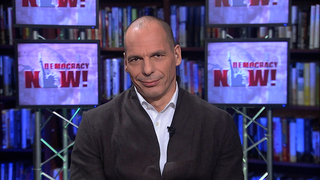

To discuss the latest in Greece, I’m joined by Maria Margaronis, London correspondent for The Nation magazine. She has just returned from Greece covering the economic crisis there.

Describe what is happening in Greece, Maria.

MARIA MARGARONIS: Well, Greece is in the throes of a multiple breakdown, economic breakdown. The economy has been in recession for five years. We now have massive unemployment, homelessness among not only poorer people but also middle-class people who never would have expected to find themselves out on the streets but are losing their jobs. Unemployment among young people is about 50 percent. Those who can are leaving the country to find work elsewhere. And it’s—the scenes on the street in Athens are like nothing anyone has seen, I would say, since the 1940s: people queuing for food at soup kitchens, graffiti everywhere—

AMY GOODMAN: Maria, we’re going—we’re calling you on your land line, because, though we’re speaking to you via Skype, the sound just isn’t good enough. I think we’re going to go to a break, and then we’re going to come back, so we can make sure everyone hears what you have to say. Maria Margaronis is The Nation magazine’s London correspondent. She has just come back from Athens. This weekend, 100,000 people protested the austerity plan, which means one in five public workers will be fired. Something like 15,000 people are expected to lose their jobs. We’ll be back with Maria Margaronis in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to Maria Margaronis, on the phone now, just out of Athens, Greece. Again, describe what you found there and what is at stake, Maria, in Greece.

MARIA MARGARONIS: Well, what is at stake, Greece is in an almost—I’m sorry, should I turn off the Skype?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes, please.

MARIA MARGARONIS: I’m getting like—OK. OK, there we go.

So, what’s at stake? Greece is in an extremely difficult situation. It’s been set this impossible choice by the European Union, the European Central Bank and the IMF, which is either to default on its loans by March, when it owes a massive loan payment, or to accept this desperate austerity program, which will further sink the economy, which has been in recession now for five years and is really now in a deep depression. As you said, it involves a 22 percent cut to the minimum wage. It involves laying off not 15,000, but 150,000 public sector workers by 2016, and many other changes.

And the Greek people have really had enough of this. People are exhausted and desperate. On the street in Athens, there’s a sense of everything breaking down. A lot of stores have closed. The ones that are open all have 50 percent sales on. You see people looking through garbage for something to eat. Homelessness has increased horrendously, so that where in the past you would only see recent immigrants queuing at homeless shelters, now many Greeks who were formerly middle-class people with good jobs and laptops and cars and so on—you know, the full middle-class lifestyle—are finding themselves out on the streets.

AMY GOODMAN: What about healthcare right now, how people are getting access to healthcare, Maria?

MARIA MARGARONIS: Healthcare is also in a very difficult situation, because when you lose your job in Greece, you also lose your healthcare, so that, for example, last week I went to see a clinic that’s been set up by the Athens Doctors Association to treat people who have lost their healthcare in that way and which is being staffed by unemployed doctors. Some doctors who are working, they’re volunteering, but also young doctors who have graduated but, because there’s a complete freeze on hiring in the public sector, can’t get a job in the public health system. I spoke to one young pediatrician who has a graduate degree in child development from Denver, Colorado, who’s working there for free and who told me that a number of families are now not vaccinating their children because they can’t afford to pay for the vaccines. So, we’re on the verge of a health disaster in Greece, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the position of the Greek government, the power of the protesters, and whether there’s any sense that this can be turned around.

MARIA MARGARONIS: OK. The Greek government voted—it’s a coalition government between—it used to be the three parties: the two main parties—the center-right and the center-left—with a far-right party called LAOS. Now, LAOS pulled out before the last austerity vote, because its popularity was dropping as a result of supporting the austerity measures. And we have a caretaker prime minister, Lucas Papademos, who is a former banker from the European Central Bank, who is an appointed prime minister. The vote on—during the vote on Sunday, a third of MPs voted against the new measures—that is, for default, effectively—which is quite an extraordinary number. And as a result, a number of MPs were expelled from the two main parties. So there’s a rejigging of the political system going on now. There’s general rage in Greece with the old politicians for having brought the country to this point. And there’s a real lack of new blood in Parliament, people who people trust to be able to turn things around.

The protests are also a complex scene, because what you see on the street in Athens, both in October and now in—on Sunday, is a complete cross-section of people from all walks of life, all ages—pensioners, working people, unemployed people, students, everybody. There’s also the large group now of hooded black-clad protesters who also are a complex scene. There’s a quite a strong anarchist movement in Greece. Some of them belong to the more violent tendencies of that. There’s also some far-right involvement, possibly. And a lot of people are certain that there are some of these protesters who actually are working with the police to cause trouble. So, a huge demonstration of, I would say, well over 100,000 people in Athens on Sunday.

The first thing that happened is that the police set to with tear gas to clear people from Syntagma Square, which is in front of Parliament, because that’s where all the TV cameras of the foreign stations are lined up on the top floors of the grand hotels. And the policy in the last demonstrations has been to get people out of the square, so that, you know, the demonstration isn’t seen. And then unbelievable street battles began between the police, with tear gas and truncheons and boots, and the hooded protesters, throwing firebombs and Molotov cocktails and marble shards. And 45 buildings in Athens were set alight. It’s a miracle that nobody was killed. And Athens now looks like a devastated war zone.

There’s no—I spoke to a friend who was at those protests, and she described a feeling of real despair, that there’s no vision, there’s no sense of a way out for Greece, apart from default, which is also an extremely painful option, unless the E.U. and the ECB and the IMF change their policy, realize that austerity isn’t working, is never going to work, and that the plan that they’ve now set in motion is only going to lead Greece to default further on down the line.

AMY GOODMAN: Maria Margaronis, how are people organizing?

MARIA MARGARONIS: Well, the interesting thing that’s happening is, a lot of very small local groups, some of whom began last summer in Syntagma Square, where there was the birth of the popular democracy camp, which has now moved into the neighborhoods—so you see people organizing, sometimes through their local councils, to resist the tax that’s been placed—the property tax that’s charged through people’s electricity bill. And the penalty for nonpayment of the tax is that the electricity gets cut off. Now, the government is beginning to retreat on this, partly because a number of boroughs have organized their citizens to just not pay it.

And we’re also seeing a great outpouring of solidarity. I was at a homeless shelter in Athens last week and talking to people there. And while I was there, several people arrived with quilts and blankets. One of the things that’s happening is that you can’t tell anymore who are the clients, if you like, of these shelters and who are the volunteers. I went up to one young woman, and I said, “Hello. Are you a volunteer?” She said, “Yes, I’m a volunteer. I’m also homeless and unemployed.” And she had been sleeping on a park bench in Piraeus until she got there and is now both at the shelter and also helping at the shelter.

AMY GOODMAN: Is the fall—

MARIA MARGARONIS: So that’s the heartening thing, is people are really coming together and pulling together.

AMY GOODMAN: Is the fall of the Greek government imminent, do you think?

MARIA MARGARONIS: I don’t think so. They have now scheduled elections for April or possibly early May. I don’t think this government is going to fall before then, unless—and this is—you know, there’s still a real question as to whether the loan will be forthcoming, despite the vote in Parliament. There are still a number of steps that have to be gone through. The party leaders all have to sign up to implementing the measures before the election, which makes the election a bit of a travesty, since they won’t have any choice about what policy to pursue. And then the Bundestag has to approve it, the German Bundestag, and the troika of the E.U., the ECB and the IMF also have to approve it. So, there’s still a real possibility that that loan won’t come through, in which case we have disorderly default in March. And then, at that point, the government may fall. But if that doesn’t happen, I think we will go to elections. But those elections will be very turbulent and very unpredictable, I would say.

AMY GOODMAN: And the effect on Europe? Moody’s Service cut the debt ratings of six European nations on Monday, including Italy, Spain and Portugal—the outlooks.

MARIA MARGARONIS: Right. Well, I think what the troika are trying to do is put a firewall around Greece and somehow cauterize the problem. But I don’t think this is going to work, because I think it’s very clear now that this is a pan-European problem and its root causes are the financial crisis that began in 2008 and also the structural problems in the eurozone, where there was no—there was no policy put in place to deal with profound inequalities between the northern and the southern countries. So, unless those things are resolved, unless some kind of Eurobond system is put in place, unless some sort of investment program for the southern countries and also Ireland is put in place, the crisis in Europe will continue.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you for being with us, Maria Margaronis, speaking to us from London, just returned from Greece. She’s writing pieces for The Nation magazine and The Guardian.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, a Valentine’s treat. Stay with us.

Media Options