Guests

- Phyllis Bennisfellow at the Institute for Policy Studies. She’s written several books, including Ending the US War in Afghanistan: A Primer and Challenging Empire: How People, Governments, and the UN Defy US Power.

- Stan SloanEuropean security expert at the CIA from the late 1960s until 1999. He was also a senior specialist at the Congressional Research Service. Since retiring from government service, he has taught at Middlebury College in Vermont. His most recent book is Permanent Alliance? NATO and the Transatlantic Bargain from Truman to Obama.

As NATO concludes its largest-ever summit in Chicago, we host a debate on whether the trans-Atlantic military alliance should exist at all and its new agreement to hand over control to Afghan forces next year. “When you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When you’re a military alliance, every problem looks like it requires a military solution,” argues Phyllis Bennis, an author and fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies. ”NATO is a giant, big hammer. The problem is, Afghanistan is not a nail, Libya is not a nail. These are political problems that need to be dealt with politically. And by empowering … a military alliance, NATO is really serving to undermine the goal of the United Nations Charter, which speaks of the importance of regional organizations, in political terms, for nonviolent resolution of disputes, not to put such a primacy and privilege on military regional institutions that really reflect the most powerful parts of the world.” Speaking in support of NATO, Stan Sloan, a 30-year security analyst at the CIA and former senior specialist at the Congressional Research Service, counters: “I believe that having allies in this alliance for the United States serves our interests, serves our national interests. … [NATO] has always been a political alliance. … I think as long as the member states regard cooperation among them as valuable and even necessary if they have to use military force, they will continue to judge that we need the alliance.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: As the largest NATO summit in the organization’s 63 years came to a close, NATO leaders in Chicago endorsed plans to hand control of Afghanistan over to its own security forces by the middle of next year. The two-day meeting brought together leaders from more than 50 countries, including 28 NATO members, as well as Afghan President Hamid Karzai and Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari. Heads of state confirmed NATO combat troops would be withdrawn by the end of 2014, with only training units remaining. President Obama addressed a news conference as the summit came to an end.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Since last year, we’ve been transitioning parts of Afghanistan to the Afghan National Security Forces, and that has enabled our troops to start coming home. Indeed, we’re in the process of drawing down 33,000 U.S. troops by the end of this summer.

Here in Chicago, we reached agreement on the next milestone in that transition. At the ISAF meeting this morning, we agreed that Afghan forces will take the lead for combat operations next year in mid-2013. At that time, ISAF forces will have shifted from combat to a support role in all parts of the country. Our coalition is committed to this plan to bring our war in Afghanistan to a responsible end.

We also agreed on what NATO’s relationship with Afghanistan will look like after 2014. NATO will continue to train, advise and assist and support Afghan forces as they grow stronger. And while this summit has not been a pledging conference, it’s been encouraging to see a number of countries making significant financial commitments to sustain Afghanistan’s progress in the years ahead.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama speaking at the close of the NATO summit last night in his hometown of Chicago.

Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari received a last-minute invitation to attend the summit last week. He met only in passing with President Obama, and no agreement was reached on reopening supply routes to NATO in Afghanistan, a step seen as essential to an orderly withdrawal.

To discuss the significance of the NATO summit and the planned withdrawal from Afghanistan—and whether NATO should exist at all—we’re joined by two guests. In Washington, D.C., Phyllis Bennis, a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, she’s written a number of books, including Ending the US War in Afghanistan: A Primer and Challenging Empire: How People, Governments, and the UN Defy US Power.

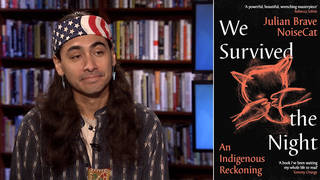

And in Burlington, Vermont, we’re joined by Stan Sloan, European security expert at the CIA from the late 1960s until 1999. He was also a senior specialist at the Congressional Research Service. Since retiring from government service, he has taught at Middlebury College in Vermont. His most recent book is Permanent Alliance? NATO and the Transatlantic Bargain from Truman to Obama.

I’d like to start with Stan Sloan. The significance of the NATO summit, and your assessment of what they concluded?

STANLEY SLOAN: Good morning. My pleasure to be with you this morning.

The NATO summit, I think, did what it was expected to do in terms of laying down a plan for the departure from Afghanistan. It is one that will satisfy nobody, but it was important that NATO follow in the steps that the United States had already taken with President Obama’s trip to Kabul and the signature of an agreement on how the United States would withdraw and what the status of its remaining forces would be afterwards. So I think that was—that was expected.

The alliance also acknowledged that it’s dealing with a very difficult set of circumstances, with resources available for defense declining in all countries, and trying to put together a plan, which is referred to, to some—by some, as “smart defense,” a plan for using resources more effectively. I know some people I’ve talked to would prefer that it be called “smarter defense,” because the allies have been trying to do this more or less throughout the history of the alliance. And so, perhaps in these times, the alliance does have to be smarter. There’s no guarantee that what has happened at Chicago will produce the kind of results that it desired, but at least it shows that all the allies are headed in the same direction.

AMY GOODMAN: Phyllis Bennis, you were in Chicago. Thousands of people were protesting outside. What do you think of the results of the summit and whether the 63-year-old organization, NATO, should exist at all?

PHYLLIS BENNIS: Thanks, Amy.

I think that we learned a number of things from the NATO summit in Chicago this past weekend. One of them was that a number of European countries have a far more functional democracy than we do, in the sense that governments are far more accountable to public opinion, particularly on the war in Afghanistan. I think that NATO played the role that it has played for a very long time, which is to provide political—and to a small degree, military and economic, but primarily political—cover to United States operations. What we see in NATO is that this is a U.S. set of decisions, and NATO is being brought on board, encouraged to keep even a few troops there. My personal favorite of the moment is Austria. They have three troops in Afghanistan at the moment. You know, this is designed to make it appear to be a multilateral operation in Afghanistan. And in fact, this is a U.S. operation and needs to be treated as such.

I think that what we’re dealing with is a scenario in which a relic of the Cold War, the NATO alliance, which was always designed in a far more offensive way than defensive, I think, has reached, if it hadn’t before—and we can argue that separately—but certainly has reached the end of any shred of legitimacy in this period of history. You know, this is really about the hammer and the nail. When you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When you’re a military alliance, every problem looks like it requires a military solution. NATO is a giant, big hammer. The problem is, Afghanistan is not a nail, Libya is not a nail. These are political problems that need to be dealt with politically. And by empowering, more than any other regional organization, a military alliance, NATO is really serving to undermine the goal of the United Nations Charter, which speaks of the importance of regional organizations, in political terms, for nonviolent resolution of disputes, not to put such a primacy and privilege on military regional institutions that really reflect the most powerful parts of the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Stan Sloan, your response?

STANLEY SLOAN: Well, my response as—I qualify it, I guess, by the fact that I’m a confirmed Atlanticist. What does that mean? It means that I believe that having allies in this alliance for the United States serves our interests, serves our national interests. For the Europeans—I just got back from Prague last week, where I was talking to citizens of the Czech Republic about this—for Europeans, having the alliance with the United States serves their interests. So, that’s my bias to—as a going-in position.

The fact is that NATO is far more than the description that we just heard. It’s always been a political alliance. I think there is, and I would agree with what Phyllis has said about the hammer and nail to the extent that NATO, or the trans-Atlantic alliance, needs to have more capacity to use the nonmilitary instruments of security more effectively. NATO does have the structure, the integrated command structure, that gives the allies the option of using military force when necessary. And if we believe that there will be cases—

AMY GOODMAN: When you say “the integrated command structure,” Stan Sloan, you mean the integrated military command structure?

STANLEY SLOAN: That’s correct. That’s correct, the integrated military command structure. That that makes it possible for the alliance to coordinate the activities, military activities, of the allies, as it did over Libya, for example, and has been doing in Afghanistan.

I do believe that in the future the alliance ought to add additional tools to its inventory. It has already said that it believes in taking comprehensive approaches to security problems. But NATO doesn’t have all of the instruments to do this. And partly it’s a political problem. Members of the European Union, some of them in the past, have not wanted to give NATO a broader mandate. But I think now it is increasingly important for the trans-Atlantic alliance, for the allies, to be able to work together in diplomacy, use of other instruments of national power, to try to prevent crises from becoming violent. We have the ability to deal with in whether they become violent, if we’re asked, if we’re given an international mandate to intervene. And then I think the alliance needs tools to do with—to deal with the post-conflict environment, when you need a peace and resolution capacity, which again requires the coordination of diplomacy and economic tools. So, the alliance—the alliance has been a lot of things for a lot of years. And I think as long as the member states regard cooperation among them as valuable and even necessary if they have to use military force, they will continue to judge that we need the alliance.

AMY GOODMAN: Phyllis Bennis, your response?

PHYLLIS BENNIS: Well, I think, first of all, we have to separate out what people think and what governments do. And I think if we look at Europe, there is a vast majority of Europeans who would, for example, want to get U.S. military forces, and particularly U.S. military equipment—namely, bombs—out of Europe. We’ve seen huge movements across Europe. So the notion that, quote, “Europeans” want this level of U.S. intervention, I think, is a very—is not really true.

I think that we have to be clear that what’s needed in the world is very much what Stan is talking about: ways of resolving disputes without resorting to violence, etc. The problem is, NATO is a military alliance. And charging it with doing nonmilitary things, giving it more power, more influence, would be a disaster. If we want to, for example, look at Kosovo, which supporters of NATO love to point to as a great human rights accomplishment, I think there are serious problems with that assessment, given the number of casualties that happened after and during NATO’s intervention. But aside from the ultimate consequences, the fact that the decision to intervene militarily in Kosovo was taken not in the U.N. Security Council, which international law and the U.N. Charter say is the only place that can decide on that kind of intervention legally, but was given instead to the NATO high command to make that decision, as if that’s somehow equally legitimate, because everyone knew that it wouldn’t be possible to get unanimity in the Security Council, that that was a serious breach of international law and a serious problem. When you had—right before the NATO intervention in Kosovo, you had the first involvement of the OSCE, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, a nonmilitary collaborative effort that had monitors on the ground. Instead of shoring them up, perhaps even providing some kind of armed protection for them so they could continue and strengthen their work, they were withdrawn. So the possibility of negotiations was simply taken away.

That’s what happened in Libya. The possibility of negotiations, based on perhaps a combined effort of the Arab League, part of whom did not support the NATO intervention, and the African Union, none of which supported the NATO intervention—there could have been some kind of negotiated settlement with far less civilian casualty levels, far lower levels of national trauma, and far more success than what we’re seeing now in Libya. So I think that this notion of relying on NATO for things outside of its purview—NATO is a great military alliance. It does a really good job at what militaries do: killing people and breaking things. When we talk about cleaning up the pieces, you don’t send in the same bull that broke the cups in the china shop.

AMY GOODMAN: Last month, we spoke to Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Davis, the most prominent active-duty servicemember to question the U.S. war in Afghanistan. In a report following his second year-long deployment in Afghanistan, Davis was skeptical about whether Afghan security forces could take on what NATO and U.S. forces have been unable to fully accomplish themselves.

LT. COL. DANIEL DAVIS: If you’re telling me that with 100,000 U.S. troops and about 50,000 NATO troops throughout the entire amount of time that we had the surge forces in there, if they were unable to materially degrade the Taliban, then what logic are you going to place that, as we’re taking 33,000 out, as we’re drawing down significant amounts of financial inputs, that suddenly the Afghan security forces, who have been unable to, with our help, to knock down the Taliban, are now suddenly going to be able to do it on their own? I don’t see the logic in that, frankly.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Davis. Stan Sloan, your response, as we wrap up?

STANLEY SLOAN: I think there are good arguments to be made on both sides of this question. Certainly, there is a possibility that once the United States has withdrawn combat forces, that the central government in Kabul could even fall and that security forces would not be able to do the mission. Who knows? It’s a difficult question. I think the President is in a difficult spot. And he’s made some choices, reflecting the desire of the American people and the people of the other alliance countries, to end the commitment to combat there, and hoping that in fact there will be some degree of stability possible in the wake of the withdrawal.

Let me make just a quick comment on the question of what NATO is and what NATO isn’t. In Kosovo—and Phyllis was talking about the decision of the allies to go into Kosovo without a U.N. Security Council resolution—that resolution was not possible because both Russia and China would veto such a resolution. And I think that probably I would agree with those who say that when something—in the view of American interests, and, for that matter, European interests, when something needs to be done, that if Russia and China are blocking it, then there need to be other options for dealing with it. And that’s what happened in Kosovo.

I also should say NATO is far more than just a military alliance. If you go back and read the North Atlantic Treaty, you’ll see that it’s a value-oriented organization. And the preamble makes it very clear that the organization is intended to support individual liberty, democracy and the rule of law. And that became very important in the 1990s, when countries that had come out from under the control of the Soviet Union wanted to reestablish their sovereignty. The 1995 Senate—NATO enlargement report made it very clear that these countries would have to establish democratic systems and control over the military by civilian authority and all of these things that these countries needed to do, because they wanted so badly to get the protection of being a NATO member. This produced a dramatic—after the revolution of getting out from the control of the Soviet Union, it produced a revolution in Europe that created more democracies and countries that then were viable as European Union members, and it created a whole different Europe. This was a political accomplishment of the alliance, not a military accomplishment.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally—

PHYLLIS BENNIS: I think—

AMY GOODMAN: —your response, Phyllis Bennis?

PHYLLIS BENNIS: I think that that was much more the accomplishment of the European Union than NATO. And I think, at the end of the day—

STANLEY SLOAN: Not true.

PHYLLIS BENNIS: —when we look at the major work that the NATO military alliance is conducting today in Afghanistan, I think that the great singer-songwriter Phil Ochs, writing about Vietnam, had it right about NATO and the U.S. in Afghanistan: we’re fighting in a war we lost before the war began.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, that issue of what you feel, Phyllis Bennis, needs to happen in Afghanistan now?

PHYLLIS BENNIS: I think there needs to be a much faster pullout, and it needs to be a complete pullout. What we’re hearing now, the decision that was endorsed—

STANLEY SLOAN: Thank you.

PHYLLIS BENNIS: —the U.S. decision endorsed in Afghanistan in the NATO summit was for a partial pullout, leaving behind somewhere probably between 16,000 and 20,000 U.S. troops, who will be doing training, but who will also be doing special operations. That means it’s Green Berets being left behind.

And I think that what we see in the future in Afghanistan is going to be very much a legacy of what this 11 years of occupation have created: a situation in which women in Afghanistan still are dying in greater numbers than anywhere in the world but Niger, where children in Afghanistan have the worst outcomes for surviving to their first birthday. This is the legacy of our 11 years of occupation and war. There needs to be a much faster withdrawal, and it needs to be based on the understanding that it is a complete withdrawal. Then we can begin the process of making good on the obligations that we have to the people of Afghanistan for reparations, for compensation for the damage that we have done to that country. But as long as U.S. troops and NATO troops are occupying the country, the process of beginning that reconstruction process can’t even begin.

AMY GOODMAN: Phyllis Bennis, I want to thank you for being with us, fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies—

PHYLLIS BENNIS: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: —written a number of books, including Ending the US War in Afghanistan: A Primer and Challenging Empire: How People, Governments, and the UN Defy US Power. And Stan Sloan, European security expert at the CIA from the late ’60s until 1999, also senior specialist at the Congressional Research Service. He now teaches at Middlebury College in Vermont. His most recent book is Permanent Alliance? NATO and the Transatlantic Bargain from Truman to Obama.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, the thousands of people who protested in the streets in NATO—what happened? Close to a hundred were arrested, five on terror-related charges. We’ll go to Chicago. Stay with us.

Media Options