Guests

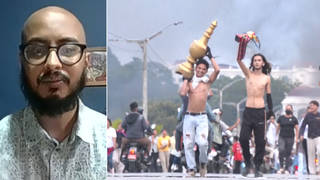

- Adhyl Polancoan eight-year veteran in the New York City Police Department. Despite being an outspoken critic of the stop-and-frisk policy, he remains on the force on a modified assignment.

The New York City Police Department’s controversial “stop-and-frisk” program was a major issue for voters going to the polls in the city’s mayoral election. The issue drew widespread attention in August when U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin found stop-and-frisk unconstitutional, saying police had relied on a “policy of indirect racial profiling” that led officers to routinely stop “blacks and Hispanics who would not have been stopped if they were white.” While she did not halt use of the tactic, Scheindlin appointed a federal court monitor to oversee a series of reforms. In a dramatic development last week, those reforms were put on hold. On Thursday, an appeals court stayed the changes, effectively allowing police officers to continue using stop-and-frisk. We get reaction from a police officer who has spoken out about problems with the program he and thousands of others are asked to carry out. Adhyl Polanco became critical of the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy when his superiors told officers to meet a quota of stops, or face punishment. Polanco made audio recordings of the quotas being described during meetings in his precinct and brought his concerns to authorities, but he said he was ignored. He then took his audio tapes to the media, including The Village Voice, where reporter Graham Rayman wrote a series called “The NYPD Tapes,” featuring several police officers like him. For several years, Polanco was suspended with pay. He has returned to work on the police force, where he has been put on modified assignment. “You cannot treat the whole black and Latino community as if they are all about to commit a crime,” Polanco says. “I’ll handcuff anybody who’s committing a crime. But when you take a male black [and say]: 'Cuff him, he doesn't look like he belongs here.’ Cuff him for what?”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn right now to an issue that we actually have addressed in the last few minutes, and it’s the issue of stop-and-frisk. Nermeen?

NERMEEN SHAIKH: The New York City Police Department’s controversial stop-and-frisk program was a major issue for voters going to the polls in the city’s mayoral election. The issue drew widespread attention in August when U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin found stop-and-frisk unconstitutional, saying police had relied on a, quote, “policy of indirect racial profiling” that led officers to routinely stop “blacks and Hispanics who would not have been stopped if they were white.” While she did not halt use of the tactic, Judge Scheindlin appointed a federal court monitor to oversee a series of reforms. New York City’s Republican mayoral candidate, Joe Lhota, vowed to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Meanwhile, the victor in Tuesday’s race, Democratic Bill de Blasio, vowed to begin the reforms right away, saying any delay would “result in irreparable harm.” Then, in a dramatic development last week, those reforms were put on hold. On Thursday, an appeals court stayed the changes, effectively allowing police officers to continue using stop-and-frisk.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’ve brought you response to the ruling from one of the lawyers who helped argue the case. Now we’re going to reaction from a police officer who has spoken out about problems with the stop-and-frisk program he and thousands of other officers are asked to carry out. Adhyl Polanco joined the New York City Police Department in 2005. In 2009, he became critical of the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy when his superiors told officers to meet a quota of stops or face punishment. He made audio recordings of the quotas being described during meetings in his precinct, and brought his concerns to authorities, but he said he was ignored. He then took his audio tapes to the media, including The Village Voice, where reporter Graham Rayman wrote a series called “The NYPD Tapes,” featuring several police officers like him. Officer Polanco also testified in the recent trial challenging the constitutionality of stop-and-frisk. For several years, he was suspended with pay. He has returned to work on the police force, where he has been put on modified assignment. Officer Polanco was recently featured in a video produced by the group Communities United for Police Reform.

ADHYL POLANCO: Believe it or not, I’ve been stopped by police after I became a cop. I used to walk to Washington Heights with two other cops friend of mine, and we would get thrown against the wall, just for walking down. I’m not saying don’t stop the criminal; I say don’t stop the innocent people.

My name is Adhyl Polanco. I’ve been a police officer since 2005. I came to New York when I was 10. I came from a Third World country, the Dominican Republic. I grew up in Washington Heights. There was shootings almost every night; it was a daily thing. The 34th Precinct used to have a cop come into my sixth-grade class. She used to come every Wednesday, and I used to look up to her like, “Oh, my god! This is what I want to do.” I mean, this is what I told my father: “I think I want to be a cop.” For me it was a dream.

In 2009, the commanding officers required us to have a one-20-and-five quota system. One-20-and-five means one arrest per month, 20 summonses per month, and five stop-question-and-frisk. So, basically, they wanted to stop at least one person a day. But what happen the day you don’t see the crime? What happened the day you don’t see the violations? People start getting creative.

We would stop a person on the street and on a corner, because the sergeant says, “Stop him.” Why? You don’t ask. You just stop him, you frisk him. If it’s possible, you search him. And these kids, sometimes they’re just walking home from school. They’re just walking to the store. They’re just—they’re not doing absolutely anything. They’re not doing absolutely anything. And it’s a really humiliating feeling. When they go through your pockets, when they stop you, you don’t have no freedom. If you stop and then tell the officer, “I’m not—I don’t have to give you my ID. I don’t have to give you my name,” which is within the law—the law allows you to do that—you’re going to get hurt. In the Bronx, you are going to get hurt.

My turning point was with a bunch of kids on a corner stopped by the commanding officer. There was a 13-year-old Mexican in the group. “Polanco, cuff him.” I said, “For what?” “Cuff him. You don’t ask me questions. Cuff him, bring him back.” His brother come to ask, “Why? What’s going on with my brother? He’s walking home from school. Officer, did he do anything stupid?” The commanding officer looked at my partner, told her, “Cuff him, too. Bring him in.” “For what?” “Oh, we will figure it out later. Just bring him in.” And that was my turning point. That was the time I said, “You know what? Why should I do it to a kid that’s just walking home from school, that we know is not doing anything? Why should I do that? This is not what I became a cop for. This is not what I wanted to do.”

I live for my kids. And I think of them. I think of them one day being slapped by a cop, like it happens so many times on the street. I’m thinking of them being handcuffed and screaming to the cop, “I haven’t done anything! I haven’t done anything! What are you—why are you arresting me? I haven’t done anything!” I don’t want them to go through that.

If you get violated by a cop, how are you going to trust that cop? How are you going to come up to him when you see something? If this is the same cop that threw me against a wall and this is the same cop that went through my private parts looking for crack that I didn’t have, why should I help him? He should be working with the community. It’s written like that. He should be getting community trust. There’s a lot of things that can make the community safer. Stopping and harassing innocent people is not going to make the community safer.

AMY GOODMAN: That was NYPD Officer Adhyl Polanco in a video produced by the group Communities United for Police Reform. When we come back, he joins us in our studio. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to a New York police officer, Adhyl Polanco, who’s been a vocal critic of the police department’s stop-and-frisk program. I spoke to him yesterday and asked him to respond to last week’s court ruling that puts on hold a sweeping set of changes to the New York City Police Department’s controversial stop-and-frisk program. In August, U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin found the program unconstitutional, saying police had relied on a policy of indirect racial profiling. She appointed a federal court monitor to oversee a series of reforms, but the city appealed her ruling, and last Thursday an appeals court stayed the changes, effectively allowing police officers to continue using stop-and-frisk. That’s where I began with Officer Polanco, asking him to respond to the appeals court ruling.

ADHYL POLANCO: Basically, I have to start with a legal statement saying I’m not here on behalf of the police department. That covers my legal—I’m obviously not here on behalf of the police department. I’m here as a citizen, which allow me to express myself in the way.

It’s a slap in the face. It’s a—you don’t expect this from a federal court. You expect this from the Board of Regents, where Bloomberg sends his people to lobby them. You expect this from a lower court that they’re politically influenced over this. You don’t expect this from the—they’re going against one of the most honorable judges they have. And that was not an appeal. People think that was not a formal appeal. That was more of a political favor, is what I call it. When the decision came over, years and years after we’ve been struggling trying to get this through there, Mayor Bloomberg asked one thing and one thing only: for the implementation not to go while he was in power. That’s all that he asked for. They created the mess. They did not want to listen to me. They did not want to listen to the City Council. They did not want to listen to some of the city lawyers who told them this was not a good lawsuit to pursue. The only purpose of this decision is to grant Bloomberg’s wish, which is that he doesn’t want to be watched while he’s in power. And it’s a shame. It’s really a shame.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to New York Police Commissioner Ray Kelly reacting to the appeals court ruling.

COMMISSIONER RAY KELLY: I have always been—and certainly haven’t been alone—concerned about the partiality of Judge Scheindlin. And we look forward to the examination of this case, a fair and impartial review of this case based on the merits.

AMY GOODMAN: Your response, Officer Polanco?

ADHYL POLANCO: He’s out of touch. Ray Kelly, when was the last time he walked the beat? When was the last time he or his family went through a stop-and-frisk? Well, we know issues with his family. But when was the last time that they went down and they asked the cops how do we feel about doing stop-and-frisk? Because I’m not the only one. I’m just the only one that had the nerve to bring it out. There’s a lot of cops under there. There’s a lot of supervisors under there, great cops, who are under fear. And for that fear, they won’t speak about what they all know is wrong. I’m not against stop-and-frisk. I’m not against stop-and-frisk the way it’s supposed to be done.

AMY GOODMAN: How is it supposed to be done?

ADHYL POLANCO: When you are—as a police officer, when you feel that somebody is about to commit a crime, had committed a crime or is in the process of committing a crime, you have the right to stop that person. You have the right to search that person, if necessary and if you [inaudible] the search. I’m not against that. And reality is that in New York, most of the people you are going to stop, regardless of what the crime is, they’re going to be black and Hispanic. That’s—we’re not arguing that. But you cannot treat the whole black and Hispanic community as we’re all about to commit a crime or as we all committed a crime or we are about to commit a crime. It’s not right. It’s not right.

AMY GOODMAN: You, yourself, have been stopped and frisk?

ADHYL POLANCO: Yes, I have.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what happened.

ADHYL POLANCO: As a police officer, and they couldn’t give me the courtesy of telling me why I was stopped.

AMY GOODMAN: You weren’t in uniform.

ADHYL POLANCO: No, I was not in uniform. I was walking in Washington Heights near my mom’s house and with two more officers. We are walking down, and all of a sudden cops roll out in an unmarked car and hit the wall. They push us against the wall. They did not ID themselves. They did not tell us, “We are cops.” Obviously we knew they were cops.

AMY GOODMAN: Were they—they were undercover.

ADHYL POLANCO: Yeah. And they—we asked them, “What’s going on? We’re on the job.” That’s how—you know, and they say—they looked at us and say—

AMY GOODMAN: You weren’t off duty at the time.

ADHYL POLANCO: I was off duty, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, you were?

ADHYL POLANCO: And they look at us and say, “What kind of job are you on?” This is how a cop talking to another say: “Look in my pocket, and you’ll see what kind of job I’m on.” And they look in my pocket, and, sadly, they gave me the ID back and kept walking. They did not say, “I’m sorry.” They did not say, “Officer, this is the reason why I stop you.” Nothing. They just kept walking.

AMY GOODMAN: And do you know them? Did you know them?

ADHYL POLANCO: No, no, no. This is—

AMY GOODMAN: And you never saw them again?

ADHYL POLANCO: Never saw them again.

AMY GOODMAN: And then talk about the moment you describe in the videotape that really made you reassess everything, that—where you were being told to stop and frisk and detain.

ADHYL POLANCO: It’s the quota system. The quota is illegal. They deny it, even with all the audio out there, even with all the victims that are coming out, even with the billions of dollars that they’re paying to cover police-related lawsuits—billions. Do you know how many after-school programs can be opened with that money, how many kindergarten and pre-K can be opened? But instead they pay a policeman’s conduct with it. It’s a really bad feeling. When they have a top-down management—Kelly and Bloomberg are synchronized: Whatever Bloomberg says, Kelly does. And they want numbers.

I would think that if crime is lower, like they say it is, which it’s not, that if things are so well in New York, you should be arresting less people, not more. You should be stopping less people, because obviously crime is lower. They’re shoving crime under the table. And I’m a big example of that. I know; I’ve done it. We were forced to do it.

AMY GOODMAN: How? Tell me what you were forced to do.

ADHYL POLANCO: You were called to a scene where the robbery happened, and they will look at the CompStat number for that week and tell you, “Oh, we’re not taking that robbery. That will put us over the top,” or, “Take the robbery, make it a lost property or make it a—anything.” Or sometimes even this—

AMY GOODMAN: It will put you over the top of too many crimes to report—

ADHYL POLANCO: Yeah, too—

AMY GOODMAN: —make the city look bad.

ADHYL POLANCO: Too many high crimes to report, so that that way they can keep saying that crime is lower. I’ve been to shootings where I’ve been told, “In the report, don’t put that a bullet went through the car. Put that a sharp object went through a car,” so now that shooting is not going to show up in the annual report of shootings. And that’s what they would do. And I do not understand how can Kelly go up on TV with a straight face and say this is not happening. I’m Officer Polanco. Officer Borelli, Officer Schoolcraft, Officer Palestro, all from different precincts, all from different around the city, we’re all saying the same thing in different precincts. But yet nobody wants to believe. And they keep saying that this is a—

AMY GOODMAN: Does this put people in danger?

ADHYL POLANCO: Of course. You hire less cops, because supposedly the crime is lower. Now you’re going to justify not hiring enough cops, because supposedly you’re doing the job.

AMY GOODMAN: So, the moment that you were being told to take kids into custody, explain that, in the Bronx.

ADHYL POLANCO: That was my breaking point. I was an assistant dean in a high school. I was a baseball coach. I have kids of my own. If you want me to arrest somebody—and I have never, ever stopped putting cuffs on anybody because they’re white, because they’re black, because they’re blue. I will handcuff anybody who’s committing a crime. But when you take that he’s a male black, he’s 14, 15, he’s walking down the corner, he doesn’t look like he belong here—”Cuff him.” “Cuff him for what?” “Cuff him. We’ll figure out inside.” What happened behind that is that the commanding officer goes to his office, and he sees the number of summonses that were written last year that he’s going to be compared to next week. So if he doesn’t have enough stop-and-frisks to match that number or double it, and if he doesn’t have enough summonses to match that number, or arrests, he’s going to go out there, he’s going to create it himself. And the quota is illegal. No matter how you cut it, it’s illegal.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go back to 2009 to a recording that you made. In this clip, we hear a delegate from the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association speaking during a roll-call meeting at the 41st Precinct where you, Officer Polanco, work.

ADHYL POLANCO: Forty-first.

AMY GOODMAN: Forty-first in the Bronx. The captain refers to 20-and-one, a reference to the demand that officers make 20 summons, five street stops and one arrest per month. So listen closely.

PATROLMEN’S BENEVOLENT ASSOCIATION DELEGATE: I spoke to the CO for about an hour and a half on the activity, 20-and-one. Twenty-and-one is what the union is backing up. They spoke to the trustees, and that’s what they want. They want 20-and-one.

AMY GOODMAN: You can hear on that tape the captain of the 41st Precinct saying, “20-and-one is what the union is backing up. They spoke to the [union] trustees. That’s what they want. They want 20-and-one.” Twenty-and-one is a reference to the demand that officers make 20 summons, five street stops and one arrest per month So the union is backing this?

ADHYL POLANCO: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Officer Polanco?

ADHYL POLANCO: Yes, the union is. And it’s sad. It’s really sad, because when you are there as an officer, you have nobody to go to. You have absolutely nobody to go to. Am I going to go to my union, who’s telling me what I have to do? Am I going to go to internal affairs, who’s not going to do anything? I thought they were. They have no integrity. When it comes to investigating themselves, they have absolutely no integrity, because they have shown. So who are we supposed to go to? Our union is not there for us. Our union is there for the police department, sadly, sadly to say.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Officer Polanco, you testified in this stop-and-frisk trial. Talk about what happened after you signed a deposition.

ADHYL POLANCO: I got approached by the Civil Liberty Union in 2009. They saw the piece on ABC-7, where I—I had nobody else to go to. I couldn’t. I was deposed in March of 2010. The next day that I show up to work—I was off for the two days that I gave the deposition, with many city lawyers—they didn’t like what I provided. They didn’t like the recordings. They didn’t like my testimony. So I was placed on a suspension, with no reason given, for about three years. I was suspended with pay for about three years, where my job was to go to internal affairs every day for five minutes in the morning, sign a piece of paper, get my full salary as a cop and go home. For three years.

AMY GOODMAN: Because they wanted you out, to stop witnessing.

ADHYL POLANCO: Because they wanted me out.

AMY GOODMAN: Perhaps to stop recording.

ADHYL POLANCO: They wanted me to isolate—they wanted to isolate me away from. But then they—about a year ago, they sent me to—I live in Rockland County. They sent me to Utica Avenue in Brooklyn, where I drive an average of five hours a day to get to work. It’s called “highway therapy.” And I pay five tolls every day to go to work.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to play the response of the NYPD’s deputy commissioner of training, James O’Keefe, when he asked about police officers who have audio recordings of officials calling for stop-and-frisk quotas. O’Keefe was questioned by reporter Kim Lengle.

KIM LENGLE: Commissioner, we’ve heard from former law enforcement officials, including current police officers, who say the training is not the problem, that the training is actually great. They’re saying it’s the pressure from the higher-ups, being forced to make more and more stops.

JAMES O’KEEFE: I don’t—I don’t know that to be true. My responsibility is to be sure that they are prepared and well trained to do what they’re required to do.

KIM LENGLE: Can you comment on the recordings that have been circulating for the past couple years?

UNIDENTIFIED: Recordings, did you say?

KIM LENGLE: Yes.

JAMES O’KEEFE: Recordings?

UNIDENTIFIED: What [inaudible] What recordings?

JAMES O’KEEFE: I’m sorry, what recordings?

KIM LENGLE: I mean, there’s recordings from, you know, officers that they’ve collected during roll calls. They’ve testified in court that they’ve collected these recordings showing that top commanders are pressuring them to make more and more stops, get more and more 250s, more and more C7s.

JAMES O’KEEFE: I wouldn’t know how to respond to a blanket statement like that.

KIM LENGLE: It’s not a blanket statement. I mean—

JAMES O’KEEFE: Yeah, I don’t know what all those recordings are. I don’t know exactly which ones you’re referring to. Our responsibility here—

KIM LENGLE: They’re in the class action lawsuit.

JAMES O’KEEFE: Our responsibility here is to be sure that everybody is properly educated and trained and prepared to do what the job assignment is. That’s—that’s the realm of what we do here.

AMY GOODMAN: So that’s New York Police Department Deputy Commissioner of Training James O’Keefe, when asked about police officers who have audio recordings of officials calling for these stop-and-frisk quotas. Your response to Officer O’Keefe, Officer Polanco?

ADHYL POLANCO: Denial, denial. He’s denying it. They’re denying it at all cost. Imagine if I didn’t make the recordings. How would I prove what I’m proving? And they’re listening to the recording, and they’re still denying it?

AMY GOODMAN: Are they targeting certain neighborhoods?

ADHYL POLANCO: Yeah. And you can make the argument that the neighbors that they ask—are targeting are the neighborhoods that have the most crime committed by black and Hispanic. But what percentage of black and Hispanic are committing this crime? And what percentage of black and Hispanic live in the neighborhood? Because one out of a hundred, when you stop—when you have one criminal, and you have 200, 300 people who are not, why will you treat everybody as a criminal?

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think the Department of Justice should investigate?

ADHYL POLANCO: They should. There’s no question that they should. What is going to be left of the black and Hispanic community after stop-and-frisk? What is going to be left? Because if you educate yourself—and I’ve seen examples of kids who are arrested for trespassing where they live, kids who are given summonses for trespassing where they live. The automatic disorderly conduct obstructing governmental activity charge, that’s when the cops stop you and you say, “I don’t have—I don’t have to talk to you. Officer, why are you going through my pocket? Why are you throwing me against the wall?” Once you ask that, then you’re going to get arrested for this kind, disorderly conduct. You’re going to spend a night in jail; the city is going to pay for it. But now you’re going to go educate yourself, like a lot of black and Hispanic do. Now you’re going to get a degree, and now you’re going to go look for a job, that’s going to deny you the job because you were—you have an arrest record. How is that helping the community?

AMY GOODMAN: Can you relate these large, you know, massive stop-and-frisks—we’re talking about what? More than 700,000 in a previous year, of largely young Latino and African-American kids—to shootings, police shootings?

ADHYL POLANCO: Ramarley Graham. Ramarley Graham is a perfect example.

AMY GOODMAN: Ramarley Graham was a teenager—

ADHYL POLANCO: Ramarley Graham, who was—

AMY GOODMAN: —who ran into his home, is flushing marijuana down the toilet of his grandmother’s apartment, and he is shot dead.

ADHYL POLANCO: That’s what they said, that he was flushing marijuana. There’s no reason to—there’s no reason to pursue somebody for marijuana. There’s no reason to go to their houses for marijuana. There’s no reason to go in the bathroom for marijuana. And there’s not a reason to put a bullet in some kid’s chest because of marijuana—if marijuana was there, because we’re getting the statement from the police department. It’s—instead of saving lives, that’s an example of taking lives, in reality.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you tell your children?

ADHYL POLANCO: I—they’re not old enough to have that conversation. I did have it with my 10-year-old. And like I said, it’s a conversation that unfortunately only some of us have to have with our kids. It’s not everybody who has to have this same conversation. Stop-and-frisk works great, it works beautifully—with white people. You know why it works so well? There’s a study out there that said that white people, when stopped, are way far more likely to have drugs or contraband on them. You know why? Because the caution is taken before stopping them. You’re not stopping them because they walk on the corner. You’re not stopping them because they’re coming from school. You are taking your time, and you have a reason to stop them. Stop-and-frisk will work beautifully if instead of 700,000 stops, you get 100,000 stops. But what is going to be your outcome rate is going to be a lot greater, because you are taking the time to police. You are taking the time to do observation.

And a lot of cops say Bloomberg is a sucker, because they go out there and they grab the first guy at the corner two hours before tour. They want to make overtime, which is not honest at all. A lot of cops want to—it’s easy. It’s the easiest way to be a cop, is to go out there and pick whoever’s at the corner, bring him back, instead of being a real cop, where you go, you interact with your community, they tell you who the drug dealers are. It takes time for you to know who’s who. But the police department don’t want time; they want numbers, and they want them right away.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you just briefly summarize the case of Officer Adrian Schoolcraft, what happened to him?

ADHYL POLANCO: Adrian Schoolcraft, almost at the same time that I spoke up, he did the same thing. He did some recordings. I was not aware. I don’t know him. And one day—I don’t know the whole full story—they went to his house, and they put him in a psych ward and did not even notify his family that he was in a psych ward for three days.

AMY GOODMAN: So he couldn’t reach his father.

ADHYL POLANCO: He couldn’t reach his father. He couldn’t do anything. And they’re still justifying everything. And those people that did that against him, there’s no accountability. Nothing happens to them.

AMY GOODMAN: And is Schoolcraft an officer today?

ADHYL POLANCO: No, he left. He left.

AMY GOODMAN: Are you concerned about continuing to speak out? Even after your years suspended with pay, you’re back on the force.

ADHYL POLANCO: I’m not giving up. I’m not giving up. Nobody’s speaking for us. I started talking against stop-and-frisk when nobody was involved, absolutely nobody.

AMY GOODMAN: That was New York Police Officer Adhyl Polanco. He was suspended with pay for more than three years after he began speaking out against the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk procedures. He testified in the recent stop-and-frisk trial here in New York. He’s now back as an active-duty police officer, though on modified assignment.

Media Options