Related

Guests

- Jules Lobelpresident of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He is the lead attorney representing prisoners at Pelican Bay in CCR’s lawsuit challenging long-term solitary confinement in California prisons. He is also a professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

- Dolores Canaleshelped start the group California Families to Abolish Solitary Confinement. Her son, John Martinez, has been held in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay for more than 12 years.

Prisoners in California have entered their 10th day of a statewide hunger strike to fight back against what they call inhumane conditions. The prisoners’ demands include a call for adequate and nutritious food, an end to group punishment, and stopping long-term solitary confinement in high-security “special housing units” where more than 3,000 prisoners are held in the isolation units with no human contact and no windows — some of them for more than a decade. We speak with Dolores Canales, a founder of California Families to Abolish Solitary Confinement and mother of John Martinez, who has been been held in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay for more than 12 years. We are also joined by Jules Lobel, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights and lead attorney representing Pelican Bay prisoners in a lawsuit challenging long-term solitary confinement in California prisons. “About 80,000 people in the United States are put into solitary,” Lobel explains. “It’s an inhumane practice, but in California they go to an extreme by placing people without any windows, without any phone calls, trying to totally isolate them.” We also hear from a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Prisoners in California have entered their 10th day of a statewide hunger strike meant to call attention to what they say are inhumane conditions. An activist who met Tuesday with men leading the strike in Pelican Bay Prison confirmed one of them had lost about 10 pounds. Authorities told Democracy Now! the number of participants now on strike is hovering around 2,500. This is California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokesperson Terry Thornton.

TERRY THORNTON: As of today, July 16, 2013, 2,493 inmates in 15 state prisons are participating in a mass hunger strike. Two hundred and one inmates in seven state prisons refused to go to work today.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Demands of the prisoners on hunger strike include a call for adequate and nutritious food, and an end to group punishment. Another key demand is a push to end long-term solitary confinement in the state’s high-security “special housing units,” known as SHUs. More than 3,000 prisoners are held in the isolation units with no human contact and no windows, some of them for more than a decade. Prison spokesperson Terry Thornton told Democracy Now! those who continue to join the strike could face additional punishment.

TERRY THORNTON: The inmates identified as leading and perpetuating the mass hunger strike, the work stoppage, this disturbance, they can be subject to disciplinary action, and it can include removal from general population housing and being placed in an administrative segregation unit. That’s pursuant to state law and CDCR’s hunger strike policy.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: A group of prisoners on hunger strike at Pelican Bay issued a new statement Tuesday saying 14 of them had been placed in administrative segregation last week in response to their protest. They wrote, quote, “Despite this diabolical act on the part of the CDCR intended to break our resolve and hasten our deaths, we remain strong and united! We are 100% committed to our cause and will end our peaceful action when CDCR signs a legally binding agreement to our demands.”

AMY GOODMAN: Meanwhile, over the weekend a rally to support the hunger strike drew hundreds from around California. More events are scheduled this week.

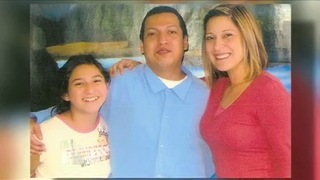

For more, we’ll go to Los Angeles, where we’re joined by Dolores Canales. She helped start the group California Families to Abolish Solitary Confinement. Her son, John Martinez, has been in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay for more than 12 years, after confidential informants labeled him a gang member.

And in Pittsburgh, Jules Lobel is with us, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, lead attorney representing prisoners at Pelican Bay in CCR’s lawsuit challenging long-term solitary confinement in California prisons.

We did invite the California Department of Corrections to join us, but they declined, citing the ongoing lawsuit against them by the Center for Constitutional Rights. In a moment, we’ll play, though, some of their comments from interviews recorded on Tuesday.

I want to welcome you both to Democracy Now! Jules Lobel, can you talk about the latest demands of the prisoners?

JULES LOBEL: Well, their main demand is to end indefinite solitary confinement, which has resulted in almost a hundred of them being there for not over a decade, but over two decades. And they’re put there not because they’ve done any misconduct in prison, not that they’ve committed an assault or other disciplinary misconduct, but simply because they’re labeled as either a gang member or even simply having some vague association with a gang, such as having some artwork of an Aztec warrior that the gang people say is related to a gang or having a tattoo or being found on some anonymous list of so-called gang members. And what they want, and their main demand, is to put an end to that system. They’re against solitary confinement generally, but if somebody is going to be put in solitary confinement, they should be put in for some definite period of time, not indefinitely, and because they’ve committed some bad act.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Jules Lobel—

JULES LOBEL: That’s their main demand.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Jules Lobel, why is it that they’re placed indefinitely in solitary confinement? This is a highly unusual practice. How and when did it begin, and on what grounds is it permissible?

JULES LOBEL: Yeah, it began in the 1980s. And what happens is, if you commit a murder in a California prison, you’re given a hearing, due process, and if you’re found guilty of murdering somebody in prison, you’re given a definite term, which can be no more than five years in solitary. If you, on the other hand, are simply labeled by some gang investigator as a member of some gang—and that could be done simply because you have artwork or because you have a tattoo or because you have a birthday card from somebody who’s in a gang, anything like that—you then are given an indefinite sentence, which can go on for years and years and years and decades. And it’s that system of labeling somebody as a gang affiliate and giving them an indefinite sentence that the prisoners want ended.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And how are these gangs defined? These are gangs within the prison or membership of gangs outside the prison?

JULES LOBEL: Yeah, they are defined by membership of gangs inside the prison, but most of the people actually are not even seen as members. They’re simply seen as, in quote, “associates,” which could mean that you just simply have a friend in a gang or that you speak to people in a gang or that you recreate with somebody in a gang. You could then be put in solitary.

AMY GOODMAN: How does solitary confinement in California compare in other places in the country and in the world? There’s another hunger strike going on right now, Jules Lobel, of course, that’s at Guantánamo.

JULES LOBEL: Exactly. And the Center, of course, is involved, representing people in both contexts, so we know them well. You know, Shane Bauer, who was in prison for four months in solitary in Iran, when he was finally released—he’s an American citizen, imprisoned in Iran—he went and visited Pelican Bay, which is the main prison where they put solitary—people in solitary in California. And they asked him, after the—been given a tour, “What’s the difference between this and what you experienced in Iran?” And he thought for a few minutes, and he said, “The difference—the main difference is, I had a window in Iran.”

My clients have spent, in some cases, over two decades in a cell with no windows. They’re not allowed any phone calls. The only way I can get a phone call is through court order. I went and got a court order. Otherwise, they’re allowed no legal phone calls, no family phone calls, no friend phone calls. This is a more draconian situation than most situations of solitary in the United States. And about 80,000 people in the United States are put in solitary. It’s an inhumane practice. But in California, they go to an extreme by placing people without any windows, without any phone calls, trying to totally isolate them.

AMY GOODMAN: Democracy Now!'s Renée Feltz asked the California Department of Corrections spokesperson, Terry Thornton, to describe the reforms implemented since the last prisoners' hunger strike in 2011.

TERRY THORNTON: The new strategy places an emphasis on documented behavior, something that the inmates were concerned about in 2011. It provides individual accountability of offenders. It’s behavior-based. It incorporates additional elements of due process now to our validation system. We’ve created this new step-down program. It gives inmates another way out of security housing units, and they don’t even have to disavow their prison gang to do it. They just have to refrain from criminal gang behavior. They need to demonstrate their commitment and their willingness to refrain from gang behavior, because you can’t really have these discussions about the security housing unit without looking at the issue of gangs in the state of California.

Inmates in California prisons have been involved in gang activity, have been entrenched in gang behavior, going back to the 1950s. Many of these prison gangs were formed in the 1950s and the 1960s, and the department has had to respond to this for decades. There is no state probably in the United States that’s had to deal with the issue of gangs as much as California has. In fact, I, last year, sat in on a briefing by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, by the Sacramento Police Department, and they talked about the activity of the more than 400 gangs just here in the city of Sacramento, in the city where I live. Gangs is a huge problem. And many of these street gangs are subservient to prison gangs and the shot callers who are incarcerated. And so, CDCR, as a law enforcement agency, has had to respond to that issue.

RENÉE FELTZ: How do you respond to those critiques that, you know, perhaps the way that an inmate can be labeled involved in gang activity have expanded instead of contracted at this point?

TERRY THORNTON: Well, one of the biggest reforms that the department implemented is that security threat group associates, which is the majority of inmates that are housed in security housing units, will no longer be placed in a SHU based solely upon their validation to that security threat group, unless there is a nexus to confirm gang activity. And so, what we use now are rules violations. An inmate can be validated as an associate of a security threat group, and that’s just the national terminology the department is using to move toward this description of any group who threatens security. So it can be a prison gang. It can be a street gang. It can be a disruptive group. It can even be a terror group. I mean, we’ve—you know, in this post-9/11 world we live in, there are all kinds of groups who threaten the safety of people, both inside of our prisons and in our communities. But what—that validation alone will not be used to place an inmate administratively into a security housing unit. It used to be the department did that. The department is no longer doing that.

We have improved the validation system, as well. And using—moving toward this behavior-based system and using rules violation reports adds that extra layers of due process, because any time that an inmate violates a rule, any rule in prison, there’s this whole process. The inmate has to be served the notice that there’s been a possible violation, probable cause. There has to be an investigation. There has to be a hearing. So we’re using that process that already exists, that has all of this due process built into it, into how we validate inmates.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokesperson Terry Thornton. Jules Lobel, your response?

JULES LOBEL: It’s disingenuous, Orwellian, and it reminds me of Alice in Alice in Wonderland when she says, “Can you make words mean what you want it to mean?” She says that they now have moved to a behavior-based system. They’re using “behavior” in way that nobody would recognize. My clients want a system where you could get put into SHU, to the solitary units, and you get out, based on whether or not you have disciplinary violations. What California defines as “behavior” is whether you have behavior such as having artwork, having a tattoo. That, they mean—that, they see as behavior. And you could still be kept in the SHU or put in the SHU for simply having tattoos, under their new system, or having artwork, under their new system. I have two clients, Gabriel Reyes and Luis Esquivel, who are associates who have spent more than 15 years in solitary, and all they’ve done is have some artwork in their cell. They’re still there. Under their new program, nothing has happened to them. And it won’t, because they claim that behavior is not behavior meaning that you’ve done some bad act—that’s what I would see it as, and I think that’s what normal Americans would see it as, that behavior means: Have you assaulted somebody, have you killed somebody, have you created a riot? They mean as behavior: Have you—do you have artwork in your cell, or do you have a tattoo? That’s your behavior. And it’s not behavior in terms of disciplinary misconduct.

You know, 10 years ago, California instituted a reform where they said you’re going to be able to get out if you are inactive. And every six years, which is an enormously long period of time, they review people to see whether they’re inactive. And my guys are sitting there in their cells saying, “We’re inactive. We’re not doing anything. We’re not engaged in any disciplinary misconduct.” But they define “inactive” — “active” as simply having a birthday card or having a tattoo or having artwork. And therefore they’re—California is a master at using words in a way that normal Americans wouldn’t recognize it.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We’d like to bring in—

JULES LOBEL: And that’s what they’re doing again.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We’d like to bring in Dolores Canales into the conversation. She is the mother of John Martinez and a member of the California Families to Abolish Solitary Confinement. Dolores, can you speak about the experience of your son, John Martinez, and his participation in this case and the letter that he’s recently written?

DOLORES CANALES: Yes. Good morning. Thank you for having me.

My son has been held in solitary confinement going on 13—almost 13 years now. He did spend 10 of those years, though, in Corcoran State Prison solitary confinement, and then he was transferred about two-and-a-half years ago to Pelican Bay. And my son is, you know, a self-proclaimed jailhouse lawyer. He has studied in civil litigation, paralegal studies, and such. And what I have found, through this organization that we’ve now founded, is that numerous prisoners that are housed in the solitary confinement unit are actually jailhouse lawyers, as you would say, that are knowledgeable in the law, that utilize the appellate process that Terry Thornton herself was talking about that they have within the prison system. And this appellate process that she was also speaking of, you’re not even legally entitled to enter into the courts until you’ve exhausted the system within, which means filing numerous levels of appeals and being heard by their same officers. So, oftentimes they’re delayed, or they’re actually denied, and, you know, you just have to keep going through this until you’ve exhausted that whole system.

And for me, since my son has been transferred to Pelican Bay State Prison, it’s been hard. It’s been really hard, because, of course, you have society that says, you know, “Who cares about the prisoner?” and “Let them die in there.” And then you have a system that was designed to create—to create, you know, suicidal tendencies or to go insane. And I think that, you know, Dr. Patterson’s report says it all, in his 354-page report, where he lists 34 suicides throughout the year of 2011 that all took place in solitary confinement, in either the administrative segregation housing unit or the security housing unit. And this is where my son is housed. My son is housed maybe in a cell where the prisoner there before him might have took his own life or went mad. You know, my son is housed in a cell that, just as Jules Lobel was saying, there is no window. You don’t know when day transitions into night. You just go by the food tray that they slide you, if it’s a breakfast tray or a dinner tray. And to know that even their yard, it just exists of another cell. They bring them out, and they put them in another cell surrounded by 20-feet brick walls and the sky covering covered in Plexiglas. And I think, for me, that is just the most troubling, that I feel myself at times as if I’m buried alive, as I feel myself that I wake up in the night and I can’t breathe and I have anxiety, because I just imagine what it’s like to be entombed day in and day out in a cement cell like that. Not just—

AMY GOODMAN: Dolores, when was the last time that John saw natural light?

DOLORES CANALES: It was on the bus ride. It was about two-and-a-half years ago, when he was transferred from the Corcoran to Pelican Bay.

AMY GOODMAN: And why is he in solitary confinement?

DOLORES CANALES: He is there—it’s not for any rules violations report, as Mr. Lobel was referring to. It’s the—they use a system of things, like they could use a drawing. They use other prisoners’ statements against them. You know, their name could be in a note. They didn’t even have to have the note. Somebody else might have had a note, and they said their name’s in it. It’s things like that. It’s an accumulation of things like that.

AMY GOODMAN: How do you know he is on hunger strike?

DOLORES CANALES: Well, I went to go see him the 4th of July weekend. And, you know, I was very emotional because I knew that July 8th they were going to start a third hunger strike now. And I just—you know, I was—I was just asking him, you know, please not to do it, or maybe just to do it for two or three days. You know, you just—you don’t want to see your loved one go through this. And he looked at me, and he said, “Mom, I like to eat.” He said—you know, he said, “I love food.” And then he said, “We’ve been in the courts. We’ve used our 602. There’s been litigation, you know, going all the way back to the Castillo v. Alameida case.” And he said, “Can you tell us another option? Can you tell us what we can do that would make a difference, you know, to change things?” he says, “Because if you have a better solution, I’d love to hear it.” And I sat there, and I just stared, because what we hear over and over with our organization is we get letters that the men are still going to their committee reviews to be reviewed to be released, and that IGI is still saying, “Oh, you have a drawing,” or, “We just searched your cell, and your name was in a note,” or, you know, “You had another prisoner’s name,” or things like that, and they’re saying, you know, “To be retained for the next six-year review.” So it does seem that, you know, they are still using the same process.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Democracy Now!’s Renée Feltz asked the California Correctional Health Care Services spokesperson, Liz Gransee, whether any of the prisoners could be force-fed as they continue their hunger strike.

LIZ GRANSEE: As for refeeding, there’s only two instances in which this could occur. If someone has not clearly stated their intentions for advanced directives and they were to lose consciousness, then we will do everything that we can to protect life and limb, just pretty much what we can to keep them alive. The second instance in which someone would be force-fed is if the participant is deemed unable to give informed consent. And the institution would have to obtain a court order to treat the participant. However, force-feeding is—shall not take place in any—anywhere but a licensed healthcare facility by licensed clinical staff.

RENÉE FELTZ: Is there any special treatment or change in the procedures followed for inmates who are in the SHU or held in solitary confinement conditions?

LIZ GRANSEE: So, all inmates are treated the same way, per our policy; however, if somebody is in a segregated housing unit, then, due to security reasons, we would have to possibly treat them in their cells, or they would be treated more in a different area. They may not go to the clinic. They may be observed in cells. And that’s more of a security issue.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: That was California Correctional Health Care Services spokesperson Liz Gransee speaking to Democracy Now!’s Renée Feltz. Jules Lobel, can you comment on what she said regarding force-feeding hunger strikers at Pelican Bay?

JULES LOBEL: Well, I hope that they are going to do everything they can to keep these people alive, because my clients don’t want to eat, but they—and they don’t want to die. They’re prepared to die if they have to, but they don’t want to. And I hope the California medical receiver does what they can to keep people alive in this situation.

AMY GOODMAN: How long do prisoners tell you they’re going to go on in this hunger strike, Jules Lobel, as we wrap up?

JULES LOBEL: Well, they tell me they are going to go on as long as it takes, because, you know, 50 years from now, we’re going to look back at this system that California and other states have—it’s not just California—and say this is state-sanctioned torture. It’s unbelievable that we put up with this and we allow this to happen in our name. And, as Dolores said, these folks have done everything they can, and they say this is their last straw, this is their last effort.

AMY GOODMAN: Jules Lobel, we want to thank you for being with us, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, head of—lead attorney representing prisoners at Pelican Bay in CCR’s lawsuit challenging long-term solitary confinement in California prisons, also a professor at University of Pittsburgh School of Law. We’re speaking to him from Pittsburgh. And we also want to thank Dolores Canales, who helped start the group California Families to Abolish Solitary Confinement. Her son, John Martinez, has been held in solitary confinement for more than 12 years, moved up near Oregon now—she was speaking to us from Los Angeles—to Pelican Bay two years ago. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

Media Options