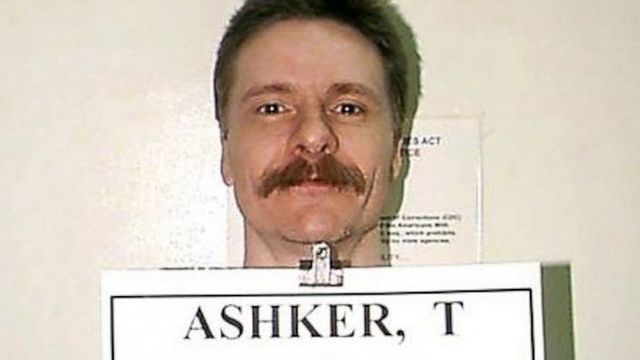

On Friday we aired part of an audio recording of Todd Ashker, one of 79 prisoners on hunger strike in California since July 8. In this extended audio, he describes how he evolved from violence to a peaceful hunger-strike protest to call for better conditions.

Ashker went to prison at age 19 for burglary and is now 50 years old. He received a life sentence after he killed an inmate in 1987, and was then sent to Pelican Bay, where he has been held in the Secure Housing Unit, or SHU. Authorities say he is still a member of the Aryan Brotherhood prison gang, though this claim is disputed by prison rights activists.

In this recording made by his attorney, Ashker says that when he entered prison as a young man he was “basically stuck on stupid, and over time being subjected to the SHU and all the abuses therein and that being the early and middle ’80s, the only way that I knew how to deal with being abused was to respond with violence.” He went on to become an accomplished jailhouse lawyer and “more class-conscious of the prisoner class as a microcosm of the working class in this country.” He says he realized “it was in our best interest to evolve our strategies and come together and utilize peaceful civil disobedience type actions in tandem with litigation to try to force the changes that were long overdue.”

Ashker spoke to his lawyers recently over a phone line from behind a glass wall, so listen closely.

TODD ASHKER: Greetings. My name is Todd Ashker, and I am from the Pelican Bay State Prison Short Corridor Collective Human Rights Movement. I am a principal representative of all similarly situated prisoners subject to long-term solitary confinement. We greatly appreciate the media’s interest and coverage of our nonviolent peaceful protest efforts towards ending long-term solitary confinement and substantive, meaningful improvement to overall prison conditions. Not limited to the Californian system, rather, we believe our efforts will benefit prison conditions as a whole across the nation.

In response to your question on how it’s come to pass that prisoners of different races and groups have become united in our struggle for prisoners and our outside loved ones to be treated humanely, with dignity and respect, in spite of our prisoner status, well, we’re glad you asked about this because we believe it’s inclusive of a powerful symbol of the wisdom and strength similarly situated people can achieve in the face of seemingly impossible odds when they collectively unite to fight for the common good of all.

It’s important to put our struggle into the proper perspective. Many of us housed in the PBSP SHU short corridor have more than 30 years in prison, most if not all of which has been spent in various isolation units wherein the fascist powers that be have subjected every one of us to progressively more punitive conditions wherein we have experienced and/or witnessed every form of physical, psychological abuse imaginable. This applies to prisoners and our outside loved ones.

As young men full of testosterone, the powers that be would regularly apply psychosocial manipulative tactics to provoke us and pit us against each other for riots and gladiator fights, while employing a no-warning-shot policy in response to any form of physical altercation. Between 1987 and 1995, the above factors were responsible for guards murdering 39 prisoners and severe permanent damage to hundreds more. We all lived this; we all had close friends maimed and murdered. Some of us were set up and shot, resulting in permanent disabilities. Support for this is included in a documentary by Abby Ginzberg titled Soul of Justice and also a video documentary of the Corcoran SHU set-ups and murders by guards created by private investigator Tom Quinn of Fresno.

Over the last three decades, we recognize the manner of which we were being pitted against each other for the purpose of statistical violence to be used in support of the agenda of the fascist prison-industrial complex—e.g. expansion in high-security cells, numbers of staff and money. Notably, in the early 1980s the California prison system received an annual budget of $40 million. Today that annual budget is $10 billion.

Many of us housed in the short corridor have been subject to PBSP SHU solitary confinement torture since it opened in 1989, 1990, wherein we’ve been housed together in an eight-cell pod. Many of us have taught ourselves and each other about the law in order to utilize the legal system to challenge those conditions. We’ve come to know, and in large part respect, one another as individuals with the common interest of bringing change to our conditions in ways beneficial for all concerned. This common experience together, with the group of us being housed together in adjacent cells, wherein we engaged in dialogue about our common experience, legal challenges, politics and the worsening conditions, enabled us to put aside any disputes we may have harbored against each other and unite as a collective group—a prisoner class—with the common goal of using nonviolent, peaceful means to force meaningful, long-overdue prison reform to happen now.

In closing, I’d like to briefly address a couple of important related points concerning our struggle for reform. Number one, we’re not seeking a free pass regarding actual sanctionable behavior. Our core demands are centered on:

A, an end to indefinite solitary confinement based on innocuous associational behavior and/or confidential information intelligence from prisoners tortured to the point of serious mental illness and agreement to become state collaborator informants.

B, individual accountability. If real evidence exists of individuals committing a serious rule violation, and he or she is found guilty, then assessing the permanent SHU term pursuant to the disciplinary matrix. This behavior-based disciplinary process has been a CDCR regulation since the 1970s.

Additionally, CDCR’s STG pilot program is not responsive to our demands. It continues to base indefinite SHU solitary confinement on confidential information intelligence without any requirement for any formal charge being filed and adjudicated for due process due to the California Prison System’s preponderance of the evidence standard. The STG pilot program is an Office of Correctional Safety power play supported by a powerful prison guard union. Between March 2012 and today, we’ve repeatedly pressed CDCR to implement a modified, small group, general population-type pilot program for short corridor prisoners. The basis for this has been in part so that we can institute our Agreement to End Hostilities, which CDCR has refused to allow us to promote. And we have presented to CDCR officials numerous times that it’s our intent to have this modified pilot program to be used as a model for the rest of the prison system on how short corridor prisoners can implement and show how our Agreement to End Hostilities can be successful, and therefore enable us to open up these prisons, stop warehousing prisoners, provide rehabilitation services, and public safety in general will be enhanced.

That’s the end of my statement.

INTERVIEWER: Anne Weills, associated with me, and I have known you for a while, and it appears to both of us that your consciousness has evolved and—evolved over the last couple years and in an extraordinary way. Can you talk about how your consciousness has evolved in the last few years to obtain this unity?

TODD ASHKER: Sure, I’d be happy to. You know, when I first came into the prison system as a young 19-year-old man, I was basically stuck on stupid. And over time, being subjected to the SHU and all the abuses therein, and back then, in the early and middle '80s, the way I knew—the only way I knew of how to deal with being abused was response in violence. And beginning in 1987, there was a group of us who were subjected to a unit called Bedrock, where in we did not have anything. We were in stripped cells. We didn't have any property, no canteen, no appliances. And we were regularly beat down. We were given short issues of food, and we were just treated less than human. And when we would respond to that in violence, that’s what they used to justify placing us in that unit.

And we all talked about how we were coming up short, how the staff were manipulating us and then using it, our response of violence, to crack down on us even more and give us more time in prison, and it was just a no-win situation for us. So we had a dialogue amongst ourselves, and we said, “Look, the law applies to the prison guards and the administration the same way it applies to us. We’re expected to follow it; so are they. Let’s learn about the law and then use the legal system to challenge these abuses.” And we implemented that, and we stuck to it. And I personally challenged prison conditions since 1988. And during that time, I’ve prevailed in some form or fashion on 15 federal civil cases.

But when it comes to the core issue of long-term solitary confinement, none of us have had success. Therefore, beginning in 2009, a group of us in the same pod together began considering our litigation strategies and how the challenges to long-term solitary confinement had not been successful. And over the next two years we all came to the conclusion that we needed to evolve our process of resistance and forcing change to the system.

And during that process of dialogue with these individuals and the material that I was reading, including material about the IRA struggle and Bobby Sands, the Irish hunger striker who united the nation, Che Guevara, Howard Zinn, Naomi Wolf and other—Thomas Paine and other activists and revolutionaries, I became more class-conscious of the prisoner class as a microcosm of the working-class poor in this country, and that it was in our best interest to evolve our strategies and come together and utilize peaceful civil disobedience-type actions, in tandem with litigation, to try to force the changes that were long overdue. And that is how we came to the point of creating our formal complaint and then moving from there to the peaceful hunger-strike protest as a collective body.

Media Options