Topics

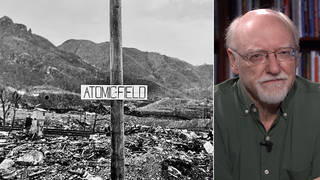

TOKYO—“I write these facts as dispassionately as I can in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world,” wrote the journalist Wilfred Burchett from Hiroshima. His story, headlined, “The Atomic Plague” appeared in the London Daily Express on Sept. 5, 1945. Burchett violated the U.S. military blockade of Hiroshima, and was the first Western journalist to visit that devastated city. He wrote: “Hiroshima does not look like a bombed city. It looks as if a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence.”

Jump ahead 66 years, to March 11, 2011, and 600 miles north, to Fukushima and the Great East Japan Earthquake, which caused the tsunami. As we now know, the initial onslaught that left 19,000 people dead or missing was just the beginning. What began as a natural disaster quickly cascaded into a man-made one, as system after system failed at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Three of the six reactors suffered meltdowns, releasing deadly radiation into the atmosphere and the ocean.

Three years later, Japan is still reeling from the impact of the disaster. More than 340,000 people became nuclear refugees, forced to abandon their homes and their livelihoods. Filmmaker Atsushi Funahashi directed the documentary “Nuclear Nation: The Fukushima Refugees Story.” In it, he follows refugees from the town of Futaba, where the Fukushima Daiichi plant is based, in the first year after the disaster. The government relocated them to an abandoned school near Tokyo, where they live in cramped, shared common areas, many families to a room, and are provided three box lunches per day. I asked Funahashi what prospects these 1,400 people had. “There’s none, pretty much. The only thing the government is saying is that [for] at least six years from the accident, you cannot go back to your own town,” he told me.

The refugees were given permits to return home to collect personal items, but only for two hours. Like Wilfred Burchett, Funahashi had to violate the government’s ban on travel to a nuclear-devastated area in order to catch the poignant moments of one family’s return on film. He explained how the family gave him one of their four permits to take the trip: “I tried to negotiate with the government, and they didn’t give me any permission to go inside there. And no other independent journalist or documentary filmmakers got permission to go inside. But I got along very well with this family from Futaba,” he explained, and sneaked back on their short trip.

The government’s refusal to grant Funahashi access is indicative of another significant problem that has emerged since the earthquake: secrecy. Japan’s conservative prime minister, Shinzo Abe, enacted a controversial state secrecy law early last December. Here in Tokyo, Sophia University Professor Koichi Nakano says of the new law, “Of course, it concerns primarily security issues and anti-terrorist measures. But … it became increasingly clear that the interpretation of what actually constitutes state secret could be very arbitrary and rather freely defined by government leaders. For example, anti-nuclear citizen movements can come under surveillance without their knowledge, and arrests can be made.”

Since the nuclear disaster, a forceful grassroots movement has grown to permanently decommission all of Japan’s nuclear power plants. The prime minister at the time of the earthquake, Naoto Kan, explained how his position on nuclear power shifted: “My position before March 11th, 2011, was that as long as we make sure that it’s safely operated, nuclear power plants can be operated and should be operated. However, after experiencing the disaster of March 11th, I changed my thinking 180 degrees, completely … there is no other accident or disaster that would affect 50 million people — maybe a war, but there is no other accident can cause such a tragedy,” he said.

Prime Minister Abe, leading the most conservative Japanese administration since World War II, wants to restart his country’s nuclear power plants, despite overwhelming public opposition. Public protests outside Abe’s official residence in Tokyo continue.

“It gives you an empty feeling in the stomach to see such man-made devastation,” Wilfred Burchett wrote, sitting in the rubble of Hiroshima in 1945. The two U.S. atomic-bomb attacks on the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have deeply impacted Japan to this day. Likewise, the triple-edged disaster of the earthquake, tsunami and ongoing nuclear disaster will last for generations. The dangerous trajectory from nuclear weapons to nuclear power is now being challenged by a popular demand for peace and sustainability. It is a lesson for rest of the world as well.

Amy Goodman is the host of “Democracy Now!,” a daily international TV/radio news hour airing on more than 1,200 stations in North America. She is the co-author of “The Silenced Majority,” a New York Times best-seller.

© 2014 Amy Goodman

Distributed by King Features Syndicate

Media Options