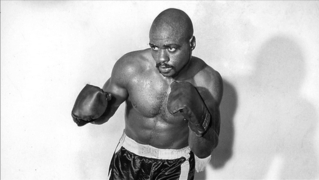

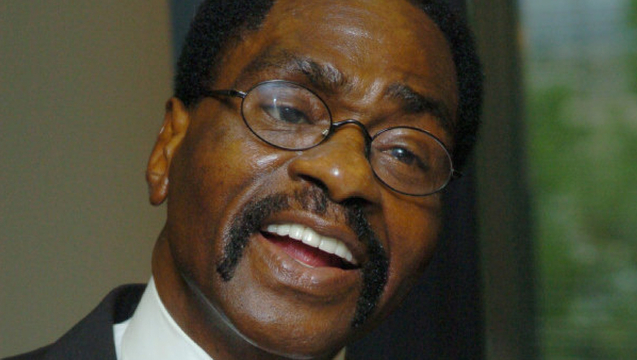

Below you can watch an extended version of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter’s passionate 1994 speech that was featured in Democracy Now!'s look back at his life and legacy. Carter was one of the most dynamic prizefighters in boxing's golden era and became an international symbol of racial injustice after his wrongful murder conviction forced him to spend 19 years in prison before he was exonerated. He died Sunday at the age of 76.

Click here to see Tuesday’s segment featuring interviews with John Artis, Carter’s co-defendant and close friend, who cared for him until his death; and Ken Klonsky, co-author of Carter’s autobiography, Eye of the Hurricane: My Path from Darkness to Freedom, and director of media relations for Carter’s group, Innocence International.

RUBIN CARTER: Thank you. Thank you for those kind words, Monique. Good evening, everybody. Good evening, every—hello out there!

It’s a pleasure for me to be here at Queen’s University. It truly is. In fact, given my history, as we’ve seen, it’s a pleasure for me to be anywhere.

I’ve been invited here to speak, but I can tell you that speaking has not always been easy for me. For the first 18 years of my life, I had a terrible speech impediment. I couldn’t talk. I stuttered badly. I couldn’t say two clear words that made any sense to anybody else but me. And people laughed at me because of it. I felt stupid. You know, I really, really felt dumb. And when they laughed, the only sound they’d hear would be my fist whistling through the air. Do I hear laughter out there? My fists did my talking. Now, that stopped the laughter for a while, but it also got me into serious trouble, and it didn’t solve the problem. I still couldn’t talk.

Being stuck in a state of silence with all that frustration was my first experience of being locked away in a prison. You see, there are prisons, and there are prisons. They may look different, but they’re all the same. They’re all confining. They all limit your freedom. They all lock you away, grind you down and take a terrible toll on your self-esteem. There are prisons made of brick, steel and mortar. And then there are prisons without visible walls, prisons of poverty, illiteracy and racism. All too often, the people condemned to these metaphorical prisons—poverty, racism and illiteracy—end up doing double time. That is, they wind up in the physical prisons, as well. Our task, as reasonable, healthy, intelligent human beings, is to recognize the interconnectedness and the sameness of all these prisons, and then do something about them, because any kind of prison is no friend of mine. It brings out the hurricane in me.

So, my connection to imprisonment is obvious. But less apparent is the impact that literacy, reading and writing, books and words, have had on my life. There were years and years when books were my only friends. And because I was able to write my own book, The Sixteenth Round, and because Lesra, the young man you saw in the video, was literate enough to read it, I was literally set free. Now, that’s the awesome power of the written word.

Both Lesra and I grew up in what can only be described as war zones, the Third World in the heart of the world’s mightiest nation. Lesra’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood looked like Dresden after the Second World War—burnt-out buildings everywhere, rubble spilling out over the sidewalks, and the people’s expressions reflecting the destitution of their surroundings. The first lesson Lesra had to learn was not his ABCs, but how to duck under the nearest parked car at the first sound of a loud noise—gunfire. He never knew whether he would survive the trip to school or from school; nevertheless, he went there every day.

And he thought he was doing well. He stood third, as we heard, in his grade 10 Brooklyn class of 40—third out of 40. He was an honors student. But what was he risking his life for? The fact is that at age 15 Lesra literally couldn’t read or write. And nobody gave a damn. As we heard Lesra say, had he not met his Canadian friends and been brought to Canada and properly educated, his future would have been just a tad different. There were three options open to him, living in the ghetto: to be strung out on drugs, to be killed on the street or to be locked up in jail. Not exactly a broad range of career opportunities. Do you know that the most common cause of death of all young black Americans is murder, that one out of every four young black men in America is under the control of the criminal justice system? One out of four—that’s outrageous. There are more black men in U.S. prisons than there are in its universities.

What were Lesra’s chances? Lesra’s chances in life were determined not by his abilities, but by an accident of birth. And I’m not talking about genetics here. I’m talking about social geography. I’m talking about people who, because of an accident of birth, are denied the kind of quality most people in the United States and Canada not only take for granted, but claim as their birthright. Lesra’s dream as a young boy was to become a lawyer. Now, he didn’t exactly know what lawyers did, but he did know that lawyers made a great deal of money when people were in trouble. And in his world, everybody was always in trouble. But Lesra was going to need a lawyer long before he ever had the ability to become one.

Now, Lesra, as we’ve seen, was not stupid. Rather, he was the product of a stupid society which for over 300 years systematically denied him human basic—basic human rights. How many of you know it was a crime during slavery to teach a black person how to read or write? How many of you knew that? Thank you. Thank you. Black people were the only group of so-called immigrants to the New World who were denied the benefits of an education. It suited America’s economic interests to keep Africans in the field instead of in the classroom. Why? As one slave master bluntly put it, “Learning,” he said, “will spoil the best nigger in the world.”