Related

Guests

- Astra Taylorauthor of the new book, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age. She is also a documentary filmmaker, who directed Examined Life: Philosophy is in the Streets and Zizek!

We are joined by author and activist Astra Taylor, whose new book, “The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age,” argues net neutrality is just the beginning of ensuring equal access and representation online. “The utopian potential of the net is real,” Taylor notes. “The problem is the underlying economic conditions haven’t changed. The same old business imperatives, the same old incentives that shaped the old model and made it so problematic are still with us. The Internet might have disrupted investigative journalism, but it didn’t disrupt advertising.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: “The King of Carrot Flowers, Pt. 1” by Neutral Milk Hotel, Jeff Mangum’s band. Jeff Mangum is the husband of our guest today, Astra Taylor. We continue today to look at equal access to the Internet. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Astra, your book, I think one of the fascinating parts, to me, is you really try to reach out to young people who are—who have been sold a bill of goods about the liberating quality of the Internet and who don’t see some of the dark side of what is happening, because obviously every new technology promises to liberate the human race. It happened, as you mentioned, with the telegraph. It then happened again with early radio. It happened again when cable came around. And now this new communications technology, the Internet, has the same promises. Your concerns about the dark side of what’s happening?

ASTRA TAYLOR: Yeah, I love that you picked up on that. I really sort of wanted to write something that would influence the younger generation the way that books by Robert McChesney influenced me when I was beginning my path to become an independent media maker, filmmaker and activist. And I think, you know, these technologies have existed long enough to kind of see that the new system is looking a lot like the old, you know, and it actually makes it—I think that people who have grown up with these technologies will have a much more realistic relationship to them, because by the time I grew up, when there’s television, I just took it for what it was. It was, you know, something that was just part of the environment, and all of the sort of romance that it had been imbued with wasn’t there.

But I think it’s important not to get cynical. The utopian potential of the net is real. It’s a remarkable innovation. And it’s true that this sort of many-to-many quality, the fact that it enables us to talk directly with people, it’s very different than the old broadcast model. The problem is the underlying economic conditions haven’t changed. The same old business imperatives, the same old incentives that shaped the old media model and that made it so problematic are still with us. So, the Internet might have disrupted investigative journalism, but it didn’t disrupt advertising, you know, and that’s what I’m trying to—that’s what I’m trying to emphasize.

AMY GOODMAN: You say it’s a rearrangement, not a revolution. Explain.

ASTRA TAYLOR: Right. I mean, so much of the story we tell ourselves is about the revolutionary impact of this new technology. But I think continuity is as important to this story. So there are new winners and new losers. But so, for example, like we were told the old media dinosaurs were going to go extinct. Well, what we’ve seen is they’ve adapted very well. I mean, it’s exactly what Michael Copps is talking about. We have this—these old media companies, NBC, joining with the cable companies, buying up Internet startups, and so there’s this kind of integration, this merging of the new and the old that doesn’t fit into the sort of myth that we were—we’ve been telling ourselves.

AMY GOODMAN: And where does Google, Facebook all fit into this?

ASTRA TAYLOR: Right, well, you know, these companies that could portray themselves as upstarts 10 years ago have now become the biggest companies on Earth. I mean, the market capitalization of Google and Apple, they’re consistently in the top 10 technology companies, or 13 of the biggest—13 of the 30 biggest companies on Earth. Yeah, so they’re—they are the Goliaths of our age. So we have, you know, Hollywood moguls, and we have Silicon Valley tycoons, and we have them collaborating.

And the thing is that the old media model, which, again, was funded by advertising, was a situation where you could turn off your television, and you could opt out. We have a much more sort of pervasive, ubiquitous system right now. And in a way, the old problems have intensified because it’s not—it’s not just something—an ad isn’t just something you are watching, actually; now you’re being watched, you’re being tracked, you’re being monitored. I mean, the dominant business model on the Internet is surveillance. And this is going to create a lot of problems down the road. I think that we need to look ahead and look at the forces that are shaping the development of these tools.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, of course, the same gender and racial and ethnic inequities of the old system are now being replicated in the new system. I want to play a comment from reporter Amanda Hess, who wrote a story in January for Pacific Standard headlined “Why Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet.” She described the dangers women face online and her personal experience with threats from Internet trolls. This is Hess talking to PBS’s To the Contrary.

AMANDA HESS: So, this summer, I was on vacation with some of my friends in Palm Springs, and the first morning that we were there, I got a text message from my friend on the East Coast. It was about 5:30 California time. And I woke up, and she had texted me to say that she’d found a Twitter account that seemed to have been created for the purposes of making threats to me. So I groggily went over to my computer, looked at the account, and it was about seven tweets that were saying things like “I’m going to come to your house and rape you and remove your head,” saying that we lived in the same state and that social violence against people like me was really important.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That’s reporter Amanda Hess. One of the chapters in The People’s Platform by our guest, Astra Taylor, is titled “Open Systems and Glass Ceilings: The Disappearing Woman and Life on the Internet.”

ASTRA TAYLOR: Yeah, I talk about the gender dynamics in—when I’m sort of challenging the idea that the Internet is a meritocracy. The idea was that we would all be able to kind of transcend our bodies, our real-world identities, and go be whoever we wanted to be on the Internet, and the best would inevitably rise to the top. So I look at the way that, you know, old hierarchies carry over. And so, one aspect of that is the issue of persistent discrimination online. And it’s harder to measure in a network space, where it seems like, well, you know, if you look over here, there’s a whole lot of women; you know, maybe they just don’t want to participate.

But Amanda Hess did a fantastic job of challenging that myth and telling a personal story that was pretty dark and scary. But she’s not alone. There are so many women in the last few months who have come forward with similar tales of discrimination and harassment. And it’s not just anecdotal. I quote a study in one of the chapters that if you use a female user name online, then you get 25 times the harassing messages of a gender-neutral screen name. And so, you know, we just have to be aware of the way that these, you know, inequalities of the old world have carried over. And it’s a challenging—it’s a real challenging issue to figure out how to remedy, because, you know, who’s in charge? Who’s in charge of enforcing equality or silencing hate speech?

AMY GOODMAN: In this last minute, Astra, I think the power of your book, The People’s Platform, is the taking back power and culture in the digital age, that you don’t give up, that you say there are ways to fight back, not to reinforce the status quo that’s reflected in the old media, actually being transferred over to the new media. What are the most effective ways?

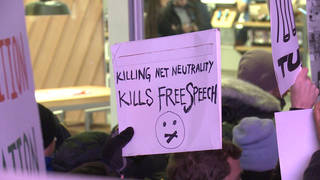

ASTRA TAYLOR: Oh, there are so many things we have to do. I mean, net neutrality is the foundation, and so joining the fight, joining groups like Demand Progress and Free Press in that struggle. But as I argue in the book, a neutral network is just the beginning, actually, and it doesn’t solve the problems of the old media model, because there’s still centralization, there’s still consolidation, there’s still commercialism. And those are things we have to address head-on. We need to think of an alternative to the advertising model that’s dominant online and find other sustainable ways of funding culture and social media and funding our future.

AMY GOODMAN: Astra Taylor, thanks so much for being with us, author of the new book, The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age. She’s also a documentary filmmaker, who directed Examined Life: Philosophy is in the Streets and Zizek! about the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. When we come back, it’s the 50th anniversary of the World’s Fair. It took place here in New York in Queens. We’ll speak with two leaders of the protest that took place outside the World’s Fair. Stay with us.

Media Options