Guests

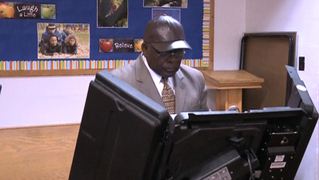

- Art McCoyfirst African-American superintendent of the Ferguson-Florissant School District. He was named to the position in 2010 and served until he resigned in March, after he had been placed on administrative leave in November of last year. He is currently an adjunct professor of education at the University of Missouri and is on the board of the Urban League’s St. Louis chapter.

As protests continue in Ferguson, we are joined by Art McCoy, who in 2010 became the first African-American school superintendent of the Ferguson-Florissant School District. But three years later, McCoy was suspended without explanation, setting off a controversy that led to his resignation earlier this year. At the time of his suspension, there were no African Americans on the school board, even though three-quarters of the district’s students were black. McCoy is currently an adjunct professor of education at the University of Missouri and is on the board of the Urban League’s St. Louis chapter.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Clearly, many issues, long-festering issues, are coming to the surface right now. You have a police force in Ferguson, 53-member police force; 50 of them are white officers. This is in a city, in Ferguson, 67.4 percent black, 28.7 percent white. Five of the six city councilmembers are white. Six of seven school board members are white, which brings us to Dr. McCoy, the first superintendent of the Ferguson-Florissant School District, who left in March under a lot of controversy. Can you talk, Dr. McCoy, about these underlying issues of lack of representation?

ART McCOY: Well, definitely. I did serve as the first African-American superintendent of the Ferguson-Florissant School District. I also was the youngest superintendent in the area at age 33. I’ve been in the school district for six years and worked very closely with each of the individual officials in the city of Ferguson, as well as other surrounding cities which the school district covered, which include Florissant, Berkeley, Cool Valley and a few other fringent cities, even a little bit of Hazelwood.

And so, the bottom line is, there is not an equal proportion of representation of leaders to those who they are leading. So, those who the constituents are being served by, ultimately, are representative of a population that’s been within that region for 50-plus years and have a different view, and sometimes an even totally different standpoint, on how things should occur, how things should be governed. You know, I think that a lot of what we see occurring is a result of too many insulated individuals being guided by a narrow view or parochial view of what should be done and how people wish to be served.

As a school official and superintendent, part of my goal was to bring equity to the region by making sure that there was an adequate representation of principals and of teachers that matched the students that we served, and we made some strides in that area. The other initiative was to bring jobs. We were proud and I was proud to be a recipient of Harvard’s Pathway to Prosperity grant, one of three districts in the state to do so, to bring job-training skills, of advanced manufacturing and other skills, so that students can earn the skills, as well as receive jobs while they’re still juniors and seniors. So, a lack of resources for jobs, a lack of resources for representation, all of that just helps to serve to give voice to what individuals need—and not just some individuals, but all individuals.

And so, I’ll say that, you know, in my situation, there was over 2,000 people who assembled, one week after I was on administrative leave, to voice their displeasure. However, there was only 10 percent voter turnout just several months later to elect who should be in the seats of the actual board chair, as well as other seats such as city councilman and so forth. And so, you know, there’s a strong emotional chord that’s been struck anytime a leader or champion, or someone that looks like you, sounds like you or represents you, falls. But I think riot is the language of the unheard, and protest is the speech act of a democracy that says, “You are a public servant and here to serve me, too.” And I don’t blame those for voicing their opinion, but I do think we need people that are on the ground that represent all people, and not just by words, but by action, by deed, by creed, by ethnicity and intent. And so, I think that’s important.

The other factor here that I might, you know, have to note out is that there are some people who want—well, everyone wants justice, but there are some people who want justice as equal action, which means an eye for an eye, a death for a death. There are some people who want justice as incrimination, to put someone in jail, take the freedom away, because we’ve been—we being those who have been oppressed—have been in a situation of less freedom, less opportunity. And there’s others that want justice by means of due process under law. So the bottom line is, I think it’s time for all voices to be honored, and at all levels, and have representation to have a common understanding of what justice is and how to proceed in the right manner.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it sounds like a lot of what happened around your case, Dr. Art McCoy, as the first African-American superintendent of the Ferguson-Florissant School District—I mean, when you had thousands of people attending this overwhelmingly white school board meeting, the festering sense that they could not turn around your being pushed out. I mean, although you resigned, many talk about it as you being fired.

ART McCOY: Mm-hmm. Well, I think what was important to me was to make sure that in all that I do, that I bridge gaps and be someone who is a bridge builder and someone who doesn’t contribute to a festering civil war. And so, my goal and part of my responsibility was to make a determination as to whether to file a lawsuit, whether to go through the actions of the NAACP, which was summoned as a result of this, and to move in that direction, or whether to act independently. And it was important to me that I express the fact that I’m invested in the community, that I’m a part of the community, born in the community, been here all my life with the community, and that no one can send me away from the community. And so, I still lead in the region and in that area, but in a different capacity.

So the question as to whether resign or whether being fired, it was one of technicality, because bottom line is, for six months—six months—there were waiting periods, discussion periods, some protesting, and even students who chose to make signs and step out of classrooms and even ask me whether to march and not show up to school. And I think that’s an important point, because school has been canceled yet again for at least a third day in which it was scheduled to occur in Ferguson, in part of it. And then in other school districts surrounding have canceled school today in light of the National Guard and other situations. And the bottom line is, it’s a constitutional right within the state of Missouri to have a free and appropriate public education, and these rights are now being delayed and hampered and denied because of the civil unrest and the lack of safety, as well as the lack of togetherness by adults and the treatment of our youth. It’s unacceptable for anyone to be slain in daylight and, in my opinion, not in daylight, for any reason minus attempting to kill someone else in the action.

And so, the bottom line is that, you know, many will try to make connections to my situation and this situation. And I want to say this right now, because I try not to echo other people’s sentiments unless it’s something I believe and I say I agree with them, but I don’t repeat it. But first I want to give my condolences to Michael Brown Jr.—or, Michael Brown Sr., I’m sorry, and his wife, because of the loss of a child, or the mother of Michael Brown Jr., because of a loss of a child—Lesley. I spoke with them yesterday. I extended my condolences and even gave money to support their well-being as they grieve. And it’s important to mourn with those who mourn.

I, in some people’s opinion, experienced a political torturing, some may even say a political assassination. But it was my goal to absorb that and rise above that political assassination, from the pure hatred that I had attacking me. Unfortunately, Michael Jr. does not have the opportunity to display that for himself, and so it’s up to us—and when I say “us,” I mean the white us, the black us and anything in between, the brown us—to say that we will honor this life by moving forward in a direction that helps to make this city, this town, this state, this country, this world better. And so, every child who dies—and I’ve lost over seven in one school year. I attended every funeral. I spoke to every parent, and I made sure I went to the hospital situation. And our teachers and the community even prayed and gave money to the efforts of those losses. And I think that that’s—you know, that’s my focus. That’s number one. And as long as I’m breathing, you know, as the superintendent of schools, I viewed myself as a father to 13,000 students. I operated in a way that the $150 million budget that I oversaw was something that met the needs of each child, as if I were their parent, because I, by the law, have the legal authority of loco parentis, which is “in place of parent.”

And so, I think that as our leaders, you know—and Chief Jackson, I know very well. And I’m going to say publicly, everyone makes mistakes, and he’s made some actions that people view as mistakes, but in all of my dealings with this individual, his heart was in the right place in my interactions with him, although albeit those around him may not have always had that same sentiment. Now, a heart condition is different than a head condition, which is different than a hand condition. And you take what’s in your heart, and you act it out through your thoughts in your head, and which was done by him releasing data because it was asked for—and the timing of that was God awful, it incited more anger and frustration—and then the actions by the hand, what you do, if he was going to march with those who marched in the beginning, but stopped because of a fear for life. You know, everyone in that region—and I have family who lives literally three blocks from ground zero at the QuikTrip—their threat of life is there every day. And so, you know, as we talk about my situation in relationship to the loss of one’s life, everyone’s life is at stake.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to—

ART McCOY: Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to break for a moment. We’re going to come back to this discussion and bring in some other people, as well. Art McCoy is with us, first African-American superintendent of the Ferguson-Florissant School District, who ultimately was forced out, resigned in March, by a school board. Six of the seven members of that school board were white. Was six of seven of the school board members, or were all of them white?

ART McCOY: At the time that I was there, all of them—there were no African Americans, and all of them were of Caucasian descent. One has Latino Caucasian.

AMY GOODMAN: And Reverend Clinton Stancil is with us, senior pastor of the Wayman AME Church in St. Louis. We’ll also find out, when we come back from break, why Amnesty International has sent observers into Ferguson. Stay with us.

Media Options