Topics

Guests

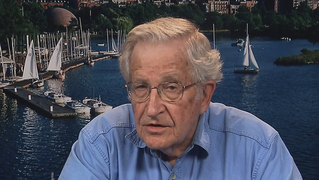

- Noam Chomskyworld-renowned political dissident, linguist and author. He is Institute Professor Emeritus at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he has taught for more than 50 years.

Part 2 of our conversation with famed linguist and political dissident Noam Chomsky on the crisis in Gaza, U.S. support for Israel, apartheid and the BDS movement. “In the Occupied Territories, what Israel is doing is much worse than apartheid,” Chomsky says. “To call it apartheid is a gift to Israel, at least if by 'apartheid' you mean South African-style apartheid. What’s happening in the Occupied Territories is much worse. There’s a crucial difference. The South African Nationalists needed the black population. That was their workforce. … The Israeli relationship to the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories is totally different. They just don’t want them. They want them out, or at least in prison.”

Click here to watch Part 1 of the interview.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. And we’re continuing our conversation with Noam Chomsky, world-renowned political dissident, linguist, author, has written many books, among them, one of the more recent books, Gaza in Crisis. I want to turn right now to Bob Schieffer, the host of CBS’s Face the Nation. This is how he closed a recent show.

BOB SCHIEFFER: In the Middle East, the Palestinian people find themselves in the grip of a terrorist group that is embarked on a strategy to get its own children killed in order to build sympathy for its cause—a strategy that might actually be working, at least in some quarters. Last week I found a quote of many years ago by Golda Meir, one of Israel’s early leaders, which might have been said yesterday: “We can forgive the Arabs for killing our children,” she said, “but we can never forgive them for forcing us to kill their children.”

AMY GOODMAN: That was CBS journalist Bob Schieffer. Noam Chomsky, can you respond?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, we don’t really have to listen to CBS, because we can listen directly to the Israeli propaganda agencies, which he’s quoting. It’s a shameful moment for U.S. media when it insists on being subservient to the grotesque propaganda agencies of a violent, aggressive state. As for the comment itself, the Israel comment which he—propaganda comment which he quoted, I guess maybe the best comment about that was made by the great Israeli journalist Amira Hass, who just described it as “sadism masked as compassion.” That’s about the right characterization.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to also ask you about the U.N.’s role and the U.S.—vis-à-vis, as well, the United States. This is the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, Navi Pillay, criticizing the U.S. for its role in the Israeli assault on Gaza.

NAVI PILLAY: They have not only provided the heavy weaponry, which is now being used by Israel in Gaza, but they’ve also provided almost $1 billion in providing the Iron Domes to protect Israelis from the rocket attacks, but no such protection has been provided to Gazans against the shelling. So I am reminding the United States that it’s a party to international humanitarian law and human rights law.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Navi Pillay, the U.N. high commissioner or human rights. Noam, on Friday, this was the point where the death toll for Palestinians had exceeded Operation Cast Lead; it had passed 1,400. President Obama was in the White House, and he held a news conference. He didn’t raise the issue of Gaza in the news conference, but he was immediately asked about Gaza, and he talked about—he reaffirmed the U.S. support for Israel, said that the resupply of ammunition was happening, that the $220 million would be going for an expanded Iron Dome. But then the weekend took place, yet another attack on a U.N. shelter, on one of the schools where thousands of Palestinians had taken refuge, and a number of them were killed, including children. And even the U.S. then joined with the U.N. in criticizing what Israel was doing. Can you talk about what the U.S. has done and if you really do see a shift right now?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, let’s start with what the U.S. has done, and continue with the comments with the U.N. Human Rights Commission. Right at that time, the time of the quote you gave over the radio—that you gave before, there was a debate in the Human Rights Commission about whether to have an investigation—no action, just an investigation—of what had happened in Gaza, an investigation of possible violations of human rights. “Possible” is kind of a joke. It was passed with one negative vote. Guess who. Obama voted against an investigation, while he was giving these polite comments. That’s action. The United States continues to provide, as Pillay pointed out, the critical, the decisive support for the atrocities. When what’s called Israeli jet planes bomb defenseless targets in Gaza, that’s U.S. jet planes with Israeli pilots. And the same with the high-tech munition and so on and so forth. So this is, again, sadism masked as compassion. Those are the actions.

AMY GOODMAN: What about opinion in the United States? Can you talk about the role that it plays? We saw some certainly remarkable changes. MSNBC had the reporter Ayman Mohyeldin, who had been at Al Jazeera, very respected. He had been, together with Sherine Tadros, in 2008 the only Western reporters in Gaza covering Operation Cast Lead, tremendous experience in the area. And he was pulled out by MSNBC. But because there was a tremendous response against this, with—I think what was trending was “Let Ayman report”—he was then brought back in. So there was a feeling that people wanted to get a sense of what was happening on the ground. There seemed to be some kind of opening. Do you sense a difference in the American population, how—the attitude toward what’s happening in Israel and the Occupied Territories?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Very definitely. It’s been happening over some years. There was a kind of a point of inflection that increased after Cast Lead, which horrified many people, and it’s happening again now. You can see it everywhere. Take, say, The New York Times. The New York Times devoted a good part of their op-ed page to a Gaza diary a couple of days ago, which was heart-rending and eloquent. They’ve had strong op-eds condemning extremist Israeli policies. That’s new, and it reflects something that’s happening in the country. You can see it in polls, especially among young people. If you look at the polling results, the population below 30, roughly, by now has shifted substantially. You can see it on college campuses. I mean, I see it personally. I’ve been giving talks on these things for almost 50 years. I used to have police protection, literally, even at my own university. The meetings were broken up violently, you know, enormous protest. Within the past, roughly, decade, that’s changed substantially by now that Palestinian solidarity is maybe the biggest issue on campus. Huge audiences. There isn’t even—hardly get a hostile question. That’s a tremendous change. That’s strikingly among younger people, but they become older.

However, there’s something we have to remember about the United States: It’s not a democracy; it’s a plutocracy. There’s study after study that comes out in mainstream academic political science which shows what we all know or ought to know, that political decisions are made by a very small sector of extreme privilege and wealth, concentrated capital. For most of the population, their opinions simply don’t matter in the political system. They’re essentially disenfranchised. I can give the details if you like, but that’s basically the story. Now, public opinion can make a difference. Even in dictatorships, the public can’t be ignored, and in a partially democratic society like this, even less so. So, ultimately, this will make a difference. And how long “ultimately” is, well, that’s up to us.

We’ve seen it before. Take, say, the East Timor case, which I mentioned. For 25 years, the United States strongly supported the vicious Indonesian invasion and massacre, virtual genocide. It was happening right through 1999, as the Indonesian atrocities increased and escalated. After Dili, the capital city, was practically evacuated after Indonesian attacks, the U.S. was still supporting it. Finally, in mid-September 1999, under considerable international and also domestic pressure, Clinton quietly told the Indonesian generals, “It’s finished.” And they had said they’d never leave. They said, “This is our territory.” They pulled out within days and allowed a U.N. peacekeeping force to enter without Indonesian military resistance. Well, you know, that’s a dramatic indication of what can be done. South Africa is a more complex case but has similarities, and there are others. Sooner or later, it’s possible—and that’s really up to us—that domestic pressure will compel the U.S. government to join the world on this issue, and that will be a decisive change.

AMY GOODMAN: Noam, I wanted to ask you about your recent piece for The Nation on Israel-Palestine and BDS. You were critical of the effectiveness of the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement. One of the many responses came from Yousef Munayyer, the executive director of the Jerusalem Fund and its educational program, the Palestine Center. He wrote, quote, “Chomsky’s criticism of BDS seems to be that it hasn’t changed the power dynamic yet, and thus that it can’t. There is no doubt the road ahead is a long one for BDS, but there is also no doubt the movement is growing … All other paths toward change, including diplomacy and armed struggle, have so far proved ineffective, and some have imposed significant costs on Palestinian life and livelihood.” Could you respond?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, actually, I did respond. You can find it on The Nation website. But in brief, far from being critical of BDS, I was strongly supportive of it. One of the oddities of what’s called the BDS movement is that they can’t—many of the activists just can’t see support as support unless it becomes something like almost worship: repeat the catechism. If you take a look at that article, it very strongly supported these tactics. In fact, I was involved in them and supporting them before the BDS movement even existed. They’re the right tactics.

But it should be second nature to activists—and it usually is—that you have to ask yourself, when you conduct some tactic, when you pursue it, what the effect is going to be on the victims. You don’t pursue a tactic because it makes you feel good. You pursue it because it’s going—you estimate that it’ll help the victims. And you have to make choices. This goes way back. You know, say, back during the Vietnam War, there were debates about whether you should resort to violent tactics, say Weathermen-style tactics. You could understand the motivation—people were desperate—but the Vietnamese were strongly opposed. And many of us, me included, were also opposed, not because the horrors don’t justify some strong action, but because the consequences would be harm to the victims. The tactics would increase support for the violence, which in fact is what happened. Those questions arise all the time.

Unfortunately, the Palestinian solidarity movements have been unusual in their unwillingness to think these things through. That was pointed out recently again by Raja Shehadeh, the leading figure in—lives in Ramallah, a longtime supporter, the founder of Al-Haq, the legal organization, a very significant and powerful figure. He pointed out that the Palestinian leadership has tended to focus on what he called absolutes, absolute justice—this is the absolute justice that we want—and not to pay attention to pragmatic policies. That’s been very obvious for decades. It used to drive people like Eqbal Ahmad, the really committed and knowledgeable militant—used to drive him crazy. They just couldn’t listen to pragmatic questions, which are what matter for success in a popular movement, a nationalist movement. And the ones who understand that can succeed; the ones who don’t understand it can’t. If you talk about—

AMY GOODMAN: What choices do you feel that the BDS movement, that activists should make?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, they’re very simple, very clear. In fact, I discussed them in the article. Those actions that have been directed against the occupation have been quite successful, very successful. Most of them don’t have anything to do with the BDS movement. So take, say, one of the most extreme and most successful is the European Union decision, directive, to block any connection to any institution, governmental or private, that has anything to do with the Occupied Territories. That’s a pretty strong move. That’s the kind of move that was taken with regard to South Africa. Just a couple of months ago, the Presbyterian Church here called for divestment from any multinational corporation that’s involved in any way in the occupation. And there’s been case after case like that. That makes perfect sense.

There are also—so far, there haven’t been any sanctions, so BDS is a little misleading. It’s BD, really. But there could be sanctions. And there’s an obvious way to proceed. There has been for years, and has plenty of support. In fact, Amnesty International called for it during the Cast Lead operations. That’s an arms embargo. For the U.S. to impose an arms embargo, or even to discuss it, would be a major issue, major contribution. That’s the most important of the possible sanctions.

And there’s a basis for it. U.S. arms to Israel are in violation of U.S. law, direct violation of U.S. law. You look at U.S. foreign assistance law, it bars any military assistance to any one country, unit, whatever, engaged in consistent human rights violations. Well, you know, Israel’s violation of human rights violations is so extreme and consistent that you hardly have to argue about it. That means that U.S. aid to Israel is in—military aid, is in direct violation of U.S. law. And as Pillay pointed out before, the U.S. is a high-contracting party to the Geneva Conventions, so it’s violating its own extremely serious international commitments by not imposing—working to impose the Geneva Conventions. That’s an obligation for the high-contracting parties, like the U.S. And that means to impose—to prevent a violation of international humanitarian law, and certainly not to abet it. So the U.S. is both in violation of its commitments to international humanitarian law and also in violation of U.S. domestic law. And there’s some understanding of that.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to get your response, Noam, to Nicholas Kristof on the issue of Palestinian nonviolence. Writing in The New York Times last month, Kristof wrote, quote, “Palestinian militancy has accomplished nothing but increasing the misery of the Palestinian people. If Palestinians instead turned more to huge Gandhi-style nonviolence resistance campaigns, the resulting videos would reverberate around the world and Palestine would achieve statehood and freedom.” Noam Chomsky, your response?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, first of all, that’s a total fabrication. Palestinian nonviolence has been going on for a long time, very significant nonviolent actions. I haven’t seen the reverberations in Kristof’s columns, for example, or anywhere. I mean, there is among popular movements, but not what he’s describing.

There’s also a good deal of cynicism in those comments. What he should be doing is preaching nonviolence to the United States, the leading perpetrator of violence in the world. Hasn’t been reported here, but an international poll last December—Gallup here and its counterpart in England, the leading polling agencies—it was an international poll of public opinion. One of the questions that was asked is: Which country is the greatest threat to world peace? Guess who was first. Nobody even close. The United States was way in the lead. Far behind was Pakistan, and that was probably because mostly of the Indian vote. Well, that’s what Nicholas Kristof should be commenting on. He should be calling for nonviolence where he is, where we are, where you and I are. That would make a big difference in the world. And, of course, nonviolence in our client states, like Israel, where we provide directly the means for the violence, or Saudi Arabia, extreme, brutal, fundamentalist state, where we send them tens of billions of dollars of military aid, and on and on, in ways that are not discussed. That would make sense. It’s easy to preach nonviolence to some victim somewhere, saying, “You shouldn’t be violent. We’ll be as violent as we like, but you not be violent.”

That aside, the recommendation is correct, and in fact it’s been a recommendation of people dedicated to Palestinian rights for many years. Eqbal Ahmad, who I mentioned, 40 years—you know, his background, he was active in the Algerian resistance, a long, long history of both very acute political analysis and direct engagement in Third World struggles, he was very close to the PLO—consistently urged this, as many, many people did, me included. And, in fact, there’s been plenty of it. Not enough. But as I say, it’s very easy to recommend to victims, “You be nice guys.” That’s cheap. Even if it’s correct, it’s cheap. What matters is what we say about ourselves. Are we going to be nice guys? That’s the important thing, particularly when it’s the United States, the country which, quite rightly, is regarded by the—internationally as the leading threat to world peace, and the decisive threat in the Israeli case.

AMY GOODMAN: Noam, Mohammed Suliman, a Palestinian human rights worker in Gaza, wrote in The Huffington Post during the Israeli assault, quote, “The reality is that if Palestinians stop resisting, Israel won’t stop occupying, as its leaders repeatedly affirm. The besieged Jews of the Warsaw ghetto had a motto 'to live and die in dignity.' As I sit in my own besieged ghetto,” he writes, “I think how Palestinians have honored this universal value. We live in dignity and we die in dignity, refusing to accept subjugation. We’re tired of war. … But I also can no longer tolerate the return to a deeply unjust status quo. I can no longer agree to live in this open-air prison.” Your response to what Mohammed Suliman wrote?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, several points again. First, about the Warsaw Ghetto, there’s a very interesting debate going on right now in Israel in the Hebrew press as to whether the Warsaw Ghetto uprising was justified. It began with an article, I think by a survivor, who went through many details and argued that the uprising, which was sort of a rogue element, he said, actually seriously endangered the Jews of the—surviving Jews in the ghetto and harmed them. Then came responses, and there’s a debate about it. But that’s exactly the kind of question you want to ask all the time: What’s going to be the effect of the action on the victims? It’s not a trivial question in the case of the Warsaw Ghetto. Obviously, maybe the Nazis are the extreme in brutality in human history, and you have to surely sympathize and support the ghetto inhabitants and survivors and the victims, of course. But nevertheless, the tactical question arises. This is not open. And it arises here, too, all the time, if you’re serious about concern for the victims.

But his general point is accurate, and it’s essentially what I was trying to say before. Israel wants quiet, wants the Palestinians to be nice and quiet and nonviolent, the way Nicholas Kristof urges. And then what will Israel do? We don’t have to guess. It’s what they have been doing, and they’ll continue, as long as there’s no resistance to it. What they’re doing is, briefly, taking over whatever they want, whatever they see as of value in the West Bank, leaving Palestinians in essentially unviable cantons, pretty much imprisoned; separating the West Bank from Gaza in violation of the solemn commitments of the Oslo Accords; keeping Gaza under siege and on a diet; meanwhile, incidentally, taking over the Golan Heights, already annexed in violation of explicit Security Council orders; vastly expanding Jerusalem way beyond any historical size, annexing it in violation of Security Council orders; huge infrastructure projects, which make it possible for people living in the nice hills of the West Bank to get to Tel Aviv in a few minutes without seeing any Arabs. That’s what they’ll continue doing, just as they have been, as long as the United States supports it. That’s the decisive point, and that’s what we should be focusing on. We’re here. We can do things here. And that happens to be of critical significance in this case. That’s going to be—it’s not the only factor, but it’s the determinative factor in what the outcome will be.

AMY GOODMAN: Yet you have Congress—you’re talking about American population changing opinion—unanimously passing a resolution in support of Israel. Unanimously.

NOAM CHOMSKY: That’s right, because—and that’s exactly what we have to combat, by organization and action. Take South Africa again. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Congress began to pass sanctions. As I said, Reagan vetoed them and then violated them when they were passed over his veto, but at least they were passing them. But that’s decades after massive protests were developing around the world. In fact, BDS-style tactics—there was never a BDS movement—BDS-style tactics began to be carried out on a popular level in the United States beginning in the late '70s, but really picking up in the ’80s. That's decades after large-scale actions of that kind were being taken elsewhere. And ultimately, that had an effect. Well, we’re not there yet. You have to recall—it’s important to recall that by the time Congress was passing sanctions against South Africa, even the American business community, which really is decisive at determining policy, had pretty much turned against apartheid. Just wasn’t worth it for them. And as I said, the agreement that was finally reached was acceptable to them—difference from the Israeli case. We’re not there now. Right now Israel is one of the top recipients of U.S. investment. Warren Buffett, for example, recently bought—couple of billion dollars spent on some factory in Israel, an installment, and said that this is the best place for investment outside the United States. Intel is setting up its major new generation chip factory there. Military industry is closely linked to Israel. All of this is quite different from the South Africa case. And we have to work, as it’ll take a lot of work to get there, but it has to be done.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, Noam, you say that the analogy between Israel’s occupation of the terrories and apartheid South Africa is a dubious one. Why?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Many reasons. Take, say, the term “apartheid.” In the Occupied Territories, what Israel is doing is much worse than apartheid. To call it apartheid is a gift to Israel, at least if by “apartheid” you mean South African-style apartheid. What’s happening in the Occupied Territories is much worse. There’s a crucial difference. The South African Nationalists needed the black population. That was their workforce. It was 85 percent of the workforce of the population, and that was basically their workforce. They needed them. They had to sustain them. The bantustans were horrifying, but South Africa did try to sustain them. They didn’t put them on a diet. They tried to keep them strong enough to do the work that they needed for the country. They tried to get international support for the bantustans.

The Israeli relationship to the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories is totally different. They just don’t want them. They want them out, or at least in prison. And they’re acting that way. That’s a very striking difference, which means that the apartheid analogy, South African apartheid, to the Occupied Territories is just a gift to Israeli violence. It’s much worse than that. If you look inside Israel, there’s plenty of repression and discrimination. I’ve written about it extensively for decades. But it’s not apartheid. It’s bad, but it’s not apartheid. So the term, I just don’t think is applicable.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to get your response to Giora Eiland, a former Israeli national security adviser. Speaking to The New York Times, Eiland said, quote, “You cannot win against an effective guerrilla organization when on the one hand, you are fighting them, and on the other hand, you continue to supply them with water and food and gas and electricity. Israel should have declared a war against the de facto state of Gaza, and if there is misery and starvation in Gaza, it might lead the other side to make such hard decisions.” Noam Chomsky, if you could respond to this?

NOAM CHOMSKY: That’s basically the debate within the Israeli top political echelon: Should we follow Dov Weissglas’s position of maintaining them on a diet of bare survival, so you make sure children don’t get chocolate bars, but you allow them to have, say, Cheerios in the morning? Should we—

AMY GOODMAN: Actually, Noam, can you explain that, because when you’ve talked about it before, it sort of sounds—this diet sounds like a metaphor. But can you explain what you meant when you said actual diet? Like, you’re talking number of calories. You’re actually talking about whether kids can have chocolate?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Israel has—Israeli experts have calculated in detail exactly how many calories, literally, Gazans need to survive. And if you look at the sanctions that they impose, they’re grotesque. I mean, even John Kerry condemned them bitterly. They’re sadistic. Just enough calories to survive. And, of course, it is partly metaphoric, because it means just enough material coming in through the tunnels so that they don’t totally die. Israel restricts medicines, but you have to allow a little trickle in. When I was there right before the November 2012 assault, visited the Khan Younis hospital, and the director showed us that there’s—they don’t even have simple medicines, but they have something. And the same is true with all aspects of it. Keep them on a diet, literally. And the reason is—very simple, and they pretty much said it: “If they die, it’s not going to look good for Israel. We may claim that we’re not the occupying power, but the rest of the world doesn’t agree. Even the United States doesn’t agree. We are the occupying power. And if we kill off the population under occupation, not going to look good.” It’s not the 19th century, when, as the U.S. expanded over what’s its national territory, it pretty much exterminated the indigenous population. Well, by 19th century’s imperial standards, that was unproblematic. This is a little different today. You can’t exterminate the population in the territories that you occupy. That’s the dovish position, Weissglas. The hawkish position is Eiland, which you quoted: Let’s just kill them off.

AMY GOODMAN: And who do you think is going to prevail, as I speak to you in the midst of this ceasefire?

NOAM CHOMSKY: The Weissglas position will prevail, because Israel just—you know, it’s already becoming an international pariah and internationally hated. If it went on to pursue Eiland’s recommendations, even the United States wouldn’t be able to support it.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, interestingly, while the Arab countries, most of them, have not spoken out strongly against what Israel has done in Gaza, Latin American countries, one after another, from Brazil to Venezuela to Bolivia, have. A number of them have recalled their ambassadors to Israel. I believe Bolivian President Evo Morales called Israel a “terrorist state.” Can you talk about Latin America and its relationship with Israel?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Yeah, just remember the Arab countries means the Arab dictators, our friends. It doesn’t mean the Arab populations, our enemies.

But what you said about Latin America is very significant. Not long ago, Latin America was what was called the backyard: They did whatever we said. In strategic planning, very little was said about Latin America, because they were under our domination. If we don’t like something that happens, we install a military dictatorship or carry—back huge massacres and so on. But basically they do what we say. Last 10 or 15 years, that’s changed. And it’s a historic change. For the first time in 500 years, since the conquistadors, Latin America is moving toward degree of independence of imperial domination and also a degree of integration, which is critically important. And what you just described is one striking example of it. In the entire world, as far as I know, only a few Latin American countries have taken an honorable position on this issue: Brazil, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, El Salvador have withdrawn ambassadors in protest. They join Bolivia and Venezuela, which had done it even earlier in reaction to other atrocities. That’s unique.

And it’s not the only example. There was a very striking example, I guess maybe a year or so ago. The Open Society Forum did a study of support for rendition. Rendition, of course, is the most extreme form of torture. What you do is take people, people you don’t like, and you send them to your favorite dictatorship so they’ll be tortured. Grotesque. That was the CIA program of extraordinary rendition. The study was: Who took part in it? Well, of course, the Middle East dictatorships did—you know, Syria, Assad, Mubarak and others—because that’s where you sent them to be tortured—Gaddafi. They took part. Europe, almost all of it participated. England, Sweden, other countries permitted, abetted the transfer of prisoners to torture chambers to be grotesquely tortured. In fact, if you look over the world, there was only really one exception: The Latin American countries refused to participate. Now, that is pretty remarkable, for one thing, because it shows their independence. But for another, while they were under U.S. control, they were the torture center of the world—not long ago, a couple of decades ago. That’s a real change.

And by now, if you look at hemispheric conferences, the United States and Canada are isolated. The last major hemispheric conference couldn’t come to a consensus decision on the major issues, because the U.S. and Canada didn’t agree with the rest of the hemisphere. The major issues were admission of Cuba into the hemispheric system and steps towards decriminalization of drugs. That’s a terrible burden on the Latin Americans. The problem lies in the United States. And the Latin American countries, even the right-wing ones, want to free themselves of that. U.S. and Canada wouldn’t go along. These are very significant changes in world affairs.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to Charlie Rose interviewing the Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal. This was in July. Meshaal called for an end to Israel’s occupation of Gaza.

KHALED MESHAAL: [translated] This is not a prerequisite. Life is not a prerequisite. Life is a right for our people in Palestine. Since 2006, when the world refused the outcomes of the elections, our people actually lived under the siege of eight years. This is a collective punishment. We need to lift the siege. We have to have a port. We have to have an airport. This is the first message.

The second message: In order to stop the bloodletting, we need to look at the underlying causes. We need to look at the occupation. We need to stop the occupation. Netanyahu doesn’t take heed of our rights. And Mr. Kerry, months ago, tried to find a window through the negotiations in order to meet our target: to live without occupation, to reach our state. Netanyahu has killed our hope or killed our dream, and he killed the American initiative.

AMY GOODMAN: That is the Hamas leader, Khaled Meshaal. In these last few minutes we have left, Noam Chomsky, talk about the demands of Hamas and what Khaled Meshaal just said.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, he was basically reiterating what he and Ismail Haniyeh and other Hamas spokespersons have been saying for a long time. In fact, if you go back to 1988, when Hamas was formed, even before they became a functioning organization, their leadership, Sheikh Yassin—who was assassinated by Israel—others, offered settlement proposals, which were turned down. And it remains pretty much the same. By now, it’s quite overt. Takes effort to fail to see it. You can read it in The Washington Post. What they propose is: They accept the international consensus on a two-state settlement. They say, “Yes, let’s have a two-state settlement on the international border.” They do not—they say they don’t go on to say, “We’ll recognize Israel,” but they say, “Yes, let’s have a two-state settlement and a very long truce, maybe 50 years. And then we’ll see what happens.” Well, that’s been their proposal all along. That’s far more forthcoming than any proposal in Israel. But that’s not the way it’s presented here. What you read is, all they’re interested in is destruction of Israel. What you hear is Bob Schieffer’s type of repetition of the most vulgar Israeli propaganda. But that has been their position. It’s not that they’re nice people—like, I wouldn’t vote for them—but that is their position.

AMY GOODMAN: Six billion dollars of damage in Gaza right now. About 1,900 Palestinians are dead, not clear actually how many, as the rubble hasn’t all been dug out at this point. Half a million refugees. You’ve got something like 180,000 in the schools, the shelters. And what does that mean for schools, because they’re supposed to be starting in a few weeks, when the Palestinians are living in these schools, makeshift shelters? So, what is the reality on the ground that happens now, as these negotiations take place in Egypt?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Well, there is a kind of a slogan that’s been used for years: Israel destroys, Gazans rebuild, Europe pays. It’ll probably be something like that—until the next episode of “mowing the lawn.” And what will happen—unless U.S. policy changes, what’s very likely to happen is that Israel will continue with the policies it has been executing. No reason for them to stop, from their point of view. And it’s what I said: take what you want in the West Bank, integrate it into Israel, leave the Palestinians there in unviable cantons, separate it from Gaza, keep Gaza on that diet, under siege—and, of course, control, keep the West Golan Heights—and try to develop a greater Israel. This is not for security reasons, incidentally. That’s been understood by the Israeli leadership for decades. Back around 1970, I suppose, Ezer Weizman, later the—general, Air Force general, later president, pointed out, correctly, that taking over the territories does not improve our security situation—in fact, probably makes it worse—but, he said, it allows Israel to live at the scale and with the quality that we now enjoy. In other words, we can be a rich, powerful, expansionist country.

AMY GOODMAN: But you hear repeatedly, Hamas has in its charter a call for the destruction of Israel. And how do you guarantee that these thousands of rockets that threaten the people of Israel don’t continue?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Very simple. First of all, Hamas charter means practically nothing. The only people who pay attention to it are Israeli propagandists, who love it. It was a charter put together by a small group of people under siege, under attack in 1988. And it’s essentially meaningless. There are charters that mean something, but they’re not talked about. So, for example, the electoral program of Israel’s governing party, Likud, states explicitly that there can never be a Palestinian state west of the Jordan River. And they not only state it in their charter, that’s a call for the destruction of Palestine, explicit call for it. And they don’t only have it in their charter, you know, their electoral program, but they implement it. That’s quite different from the Hamas charter.

Media Options