Related

Guests

- Dave Zirinsports columnist for The Nation magazine. His latest article is called “3 Lessons from University of Missouri President Tim Wolfe’s Resignation.” He is also the host of the Edge of Sports podcast.

- Danielle Walkermaster’s student at the Truman School of Public Affairs at University of Missouri and creator of the Racism Lives Here movement at the school. She is also a graduate research assistant for the Chancellor’s Diversity Initiative and graduate research assistant in the Department of Educational Leadership & Policy Analysis.

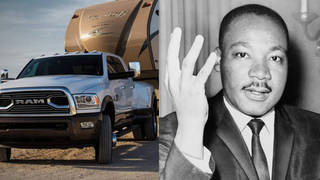

The protests at the University of Missouri have been growing for weeks, but a turning point came this weekend when African-American players on the school’s football team joined in. In a tweet quoting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the players wrote: “The athletes of color on the University of Missouri football team truly believe 'Injustice Anywhere is a threat to Justice Everywhere.'” They announced they will no longer take part in any football activities until Wolfe resigned or was removed “due to his negligence toward marginalized students’ experience.” The coach and athletic department soon came out in support. We are joined by Dave Zirin, sports columnist for The Nation magazine and the host of the Edge of Sports podcast.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: During a news conference on Monday, University of Missouri football coach Gary Pinkel said that supporting his players’ decision to go on strike was the right thing to do and that he would do it again.

GARY PINKEL: My players called me to tell me they were going to go over on campus that day and asked me if it was OK to do that. And my players are—those guys are really good leaders, and they want to get more involved with the campus. And I think—I think that’s positive, and I think that’s a positive environment to have. And then I got a call later that night about Jonathan. Guys were very, very emotional, and they were very, very concerned with his life. And then, at that time, they were discussing, you know, with me what they planned on doing this weekend. And we went back and forth. And I kept asking them, “Is it the right thing to do? Should you wait?” and so on and so forth. And they—I mean, I’m talking to guys who have tears in their eye, and they’re crying. And they asked me if I’d support them, and I said I would. I didn’t look at consequences. That wasn’t about it at the time. It was about helping my players and supporting my players when they needed me. And I did the right thing, and I would do it again.

AMY GOODMAN: Dave Zirin is sports columnist for The Nation magazine. His latest article is “3 Lessons from University of Missouri President Tim Wolfe’s Resignation.” He’s host of Edge of Sports podcast and author of a number of books.

Dave, can you talk about the significance of the—what’s called, well, University of Missouri, Mizzou football team, the African-American players coming out over racism in the country and refusing to play football until the president resigned?

DAVE ZIRIN: Well, the significance was massive, because, first and foremost, it struck an economic blow at Tim Wolfe’s chance of keeping his job. If the team had forfeited its game this weekend against BYU, the school would have had to write a check for $1 million. That’s more than twice what Tim Wolfe makes in a year.

The second part of the significance is that immediately it blew up this story on a national level, beyond which the hunger strike, beyond which the protests could have possibly imagined. For example, the subject of the football players going on strike has been wall-to-wall coverage on ESPN. So you have masses of people who read the sports page but don’t necessarily read the front page, or who click on sports Twitter and not necessarily the mainstream news, are all of a sudden reading about this story, are all of a sudden learning what’s happening at Missouri.

And I’ll tell you something: This is not just a chicken coming home to roost, it’s a golden goose coming home to roost for Tim Wolfe, because it was his—it’s been his decision in his tenure to put the football team front and center. It’s been his decision to say that he was going to cut healthcare for grad students and teachers, while at the same time investing $72 million into the football stadium. It’s been the decision of his administration, for example, to even do things like not pursue sexual assault charges against people on the football team way back in 2009, that led to the suicide of a swimmer named Sasha Courey on campus, which was one of the things that Jonathan [Butler] talked about when he talked about the climate on campus, not just about racism, but also about gender violence, also about LGBTQ rights and utter marginalization of those students.

And then the last reason why it’s significant is that we’re talking about social power. The number of African-American students at Missouri University, it’s roughly 7 percent. The number of African-American football players, we’re talking about 69 percent. So here they are at the fulcrum of the political, economic, social and psychological life of campus, but none of those billion-dollar gears move at all if they choose not to play.

AMY GOODMAN: How much is the coach paid at the University of Missouri, the coach we just heard from?

DAVE ZIRIN: That is a great question. That is a great question. Gary Pinkel, the coach, makes over $4 million a year. In other words, I’m not great at math, but he makes roughly 100 times [sic] what Tim Wolfe makes. And it reminded me of a story from Ohio State a few years back, when the school president, Gordon Gee, was talking about his own coach, Jim Tressel, and he asked if he would fire Jim Tressel. And Gordon Gee said, “I just hope he doesn’t fire me.” In one respect, this is a case, in some ways, of Gary Pinkel firing Tim Wolfe. But we have to realize that Gary Pinkel doesn’t stand with his players unless his players stand up. And his players don’t stand up unless the—without the students standing up. So the base of everything that we’ve seen happen has to do with the remarkable movement building done on the ground by students, by black students centrally, at Missouri University.

AMY GOODMAN: I think, actually, Gary Pinkel makes about eight times what Tim Wolfe made, if you said he made half a million—

DAVE ZIRIN: I’m bad at math.

AMY GOODMAN: —and Pinkel made $4 million. I want to go back for a minute to Danielle Walker, talking about what it meant for the African-American members of the football team, and then, overall, the football team, with the white coach, supporting your actions, basically, as founder of Racism Lives Here, supporting Jonathan Butler on his hunger strike.

DANIELLE WALKER: I mean, I was completely just flabbergasted that the football players, the black football players, was taking this initiative, because I understand that student athletes, especially football players, live a very different life on college—in colleges, versus, you know, traditional students who are not athletes. And so, I recognize the significance of their support and how this can really actually generate the much-needed momentum to really accomplish a lot of the demands that—once again, that students even before I was even here were asking for. So, once again, it was showing just the solidarity and how this was, you know, reaching all areas of our campus, that people were really starting—faculty, staff, you know, our student athletes were starting to understand the issues that are happening on our campus, and, more importantly, understanding that they are a stakeholder and that they have a role to play in this movement, as well. And so, I do appreciate that they finally recognized that and then understood, from where their positioned, what power and what influence that they have, and then taking that initiative, and how that definitely led to the events that unfolded yesterday.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Dave Zirin, how unusual is it for a college football team to take this stand? Now, again, it started with the African-American players—

DAVE ZIRIN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —but then the full team, with the white coaches, supported them.

DAVE ZIRIN: That’s a great question. And I think the root of that question is really sometimes we—people who care about the rights of college athletes, particularly in these revenue-producing sports, particularly black athletes who represent the heart of football and basketball, men’s sports, we often talk about them in terms of their powerlessness, and not their power, to actually stop the gears of this billion-dollar industry. And we saw it a great deal in the late '60s and early 1970s during the period that's often called the revolt of the black athlete, where you had players at schools like Syracuse, for example, say that they would not play unless a head coach that they said was racist was—had to step down, or at University of Washington, U-Dub, where players refused to take the field unless a statement against the war in Vietnam was read over the PR system. That actually really happened.

But in recent years, as the college football system has become such a multibillion-dollar leviathan, you’ve also seen athletes begin to get more restive and say, “Well, wait a minute, what about us? What about our rights?” You saw it at Northwestern University as players tried to organize a union. You saw it at Grambling University, that historic, historically black college, where players said that their working conditions, basically, their weight room was unsafe, and they would not play unless they were able to have a safe working space.

But this is above and beyond that. I mean, this is the first time you’ve seen a living, breathing connection between a football team and a campus movement. And I think what it does is it lays a handbook, really, for campus activists around the country, particularly at these big state schools, to say, “Let’s talk to the athletes. Let’s not see them as living in this separate space. Let’s actually try to connect with them. Let’s hear their grievances and see if they’re willing to hear ours, as well.”

AMY GOODMAN: Dave Zirin, I want to thank you for being with us, sports columnist for The Nation magazine. We’ll link to your article, “3 Lessons from University of Missouri President Tim Wolfe’s Resignation.” Also author of the book, Brazil’s Dance with the Devil: The World Cup, the Olympics, and the Fight for Democracy.

Media Options