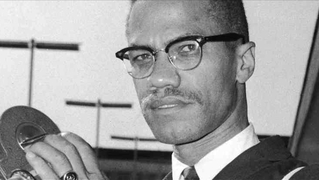

This weekend, people around the country marked the 50th anniversary of the assassination of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, known as Malcolm X — one of the most influential political figures of the 20th century. In New York City, family members and former colleagues led a memorial ceremony in the former Audubon Ballroom where Malcolm X was gunned down on February 21, 1965. The Audubon Ballroom is now the Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz Memorial and Education Center. We hear some of the event’s speakers, including Malcolm X’s daughter Ilyasah Shabazz. We broadcast an excerpt of our 2006 interview with the late civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama, who witnessed the assassination and held Malcolm X as he lay dying. We also air the Pacifica Archives recording of the 1965 eulogy delivered by the actor and activist Ossie Davis.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: This weekend, people around the country marked the 50th anniversary of the assassination of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, known as Malcolm X, one of the most influential political figures of the 20th century. Here in New York, his former colleagues were joined by family members who remembered the father of six at a memorial ceremony in the former Audubon Ballroom, where he was gunned down on February 21st, 1965. He was just 39 years old. Today, a blue light marks the spot where he was killed. This is Malcolm X’s daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz.

ILYASAH SHABAZZ: Our people cultivated this land, that was once barren, enslaved, and we can now call it the United States of America. And it’s important that we make sure that they are honored, that their lives were not in vain. And I would like to bring us into a moment of silence. It is around the time that my father was brutally assassinated, martyred, right here in this blue light. And if you could join us.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The Audubon Ballroom is now the Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz Memorial and Education Center. Saturday’s memorial there also featured several speakers and artists. Singer Sharisse “She-Salt” Ashford shared this spoken word piece at 3:10 p.m., the exact time Malcolm X was shot.

UNIDENTIFIED: Please give a warm welcome to She-Salt.

SHARISSE ”SHE-SALT” STANCIL-ASHFORD: Here, in this place, in this blessed space, where 50 years ago your life was taken in haste, was taken with hate, but, Brother Malcolm, they know. You can’t kill what God has purposed. If you bury seeds, they’ll grow. And that’s power. Three-ten, yes, that was your final hour, but your life is still speaking, your words are still teaching, and though black people still are bleeding, there are little signs of freedom. Self-determination is the reason that we keep on believing we’re seeing. There’s a worldwide revolution going on. Black folk are tired of being indicted before we’re even born, being buked and scorned, lord, for having skin of a darker hue. Got to campaign for our humanity as we’re trotting through, but still.

Who taught us to love ourselves? You. Who took our plight and then who flew across the blue waters so the world would know that the struggle is the same no matter where you go? From New York to the Congo, Mississippi to Belize, from Alabama to Mississippi, it’s the same. Please believe, Brother Malcolm. You declared this is not just an American problem, and it’s up to all Africans to band together to solve them.

Brother Malcolm, we thank you for your sacrifice. Ain’t too many out here who would give their lives for the truth. Despite bombings and the bashings, you still lived the life of courage and committed action, full of compassion, loving people, always staying in position, working overtime that we might see our condition. That was your mission. And there was no hate in your blood, just steadfast, unmoveable, boundless love and self-reliance. No, we don’t have to live in compliance with racism, oppression, sexism, all the violence against women.

Brother Malcolm, you would have something to say, because you rode with many sisters back in the day. Speaking of women, at this time I would like to pay homage to Dr. Betty, who worked night and day to preserve your legacy in a dignified way and is the very reason why we can assemble today, a mighty sister who raised your six daughters into queens, all the while becoming a doctor and fulfilling her dreams, a mighty sister who raised your six daughters into queens, all the while becoming a doctor and fulfilling her dreams. Turning tragedy into triumph, this space was created. Dr. Betty, we thank you, and we are elated.

Brother Malcolm, it’s been 50 years, and we still speak your name, brother Malcolm, the black prince that was slain. Let all the people in the place, if you will never forget, say “Ashay.”

AUDIENCE: Ashay.

SHARISSE ”SHE-SALT” STANCIL-ASHFORD: It’s been 50 years, and we still speak your name, Brother Malcolm, the black king that was slain. Let all the people in the place, if you will never forget, say, “Aameen.”

AUDIENCE: Aameen.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That was Sharisse “She-Salt” Ashford. Now I want to turn to the keynote speaker at Saturday’s memorial for Malcolm X at the former Audubon Ballroom. This is Dr. Ron Daniels.

RON DANIELS: You get a whole generation of people dealing with black power and coming to a new sense of self-awareness and so forth, all attributable to Malcolm. And, of course, we’ve spoken to his emphasis on human rights, because human rights, he said, is above civil rights. I mean, you’re not necessarily denigrating civil rights. That’s not the point. But if you’re in a society where the government is oppressing you, he said, you don’t—you can’t go to that court. If that’s who’s criminalizing you, take the criminal to court.

AMY GOODMAN: Last year, the civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama died at the age of 93 in California. Well, in 2006, I visited her in California and interviewed her for Democracy Now! She talked about the day Malcolm X was assassinated. She was with him in Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom, cradling his head as he lay dying on the stage.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: The date was February 21st. It was a Sunday. Well, prior to that date, I think that whole week there was a lot of rumors going on in Harlem that something might happen to Malcolm. But I think Malcolm showed all along, especially around that time, that there were rumors going on. He was aware, because there were things even in the newspaper, that there was some, I think—I don’t know if it was a misunderstanding or just disagreeing about some things that Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm were talking about. They were personal things. … There was disagreement between Elijah and Malcolm, and I think there was even talk that was going on, and after the assassination, however, many black people felt it could have been by people who had infiltrated or that the police department and FBI may have actually planted them in the Nation of Islam.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Yuri Kochiyama speaking in 2006. We had hoped today to be joined live by Ilyasah Shabazz, but she’s caught in serious traffic right now, so we’re going to turn to Malcolm X himself from the PBS documentary Malcolm X: Make It Plain.

MALCOLM X: And I, for one, as a Muslim, believe that the white man is intelligent enough. If he were made to realize how black people really feel and how fed up we are, without that old compromising sweet talk—why, you’re the one that make it hard for yourself. The white man believes you when you go to him with that old sweet talk, 'cause you've been sweet-talking him ever since he brought you here. Stop sweet-talking him. Tell him how you feel. Tell him how—what kind of hell you’ve been catching, and let him know that if he’s not ready to clean his house up, if he’s not ready to clean his house up, he shouldn’t have a house. It should catch on fire and burn down.

AMY GOODMAN: Half a year before his assassination, Malcolm X gave the famed speech, “By Any Means Necessary.” This is an excerpt.

MALCOLM X: One of the first things that the independent African nations did was to form an organization called the Organization of African Unity. […] The purpose of our […] Organization of Afro-American Unity, which has the same aim and objective to fight whoever gets in our way, to bring about the complete independence of people of African descent here in the Western Hemisphere, and first here in the United States, and bring about the freedom of these people by any means necessary. That’s our motto. […]

The purpose of our organization is to start right here in Harlem, which has the largest concentration of people of African descent that exists anywhere on this Earth. There are more Africans here in Harlem than exist in any city on the African continent, because that’s what you and I are: Africans. […]

The Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights are the principles in which we believe, and that these documents, if put into practice, represent the essence of mankind’s hopes and good intentions; desirous that all Afro-American people and organizations should henceforth unite so that the welfare and well-being of our people will be assured; we are resolved to reinforce the common bond of purpose between our people by submerging all of our differences and establishing nonsectarian, constructive programs for human rights; we hereby present this charter:

I. The Establishment.

The Organization of Afro-American Unity shall include all people of African descent in the Western Hemisphere […] In essence what it is saying, instead of you and me running around here seeking allies in our struggle for freedom in the Irish neighborhood or the Jewish neighborhood or the Italian neighborhood, we need to seek some allies among people who look something like we do. And once we get their allies. It’s time now for you and me to stop running away from the wolf right into the arms of the fox, looking for some kind of help. That’s a drag.

II. Self-Defense.

Since self-preservation is the first law of nature, we assert the Afro-American’s right to self-defense.

The Constitution of the United States of America clearly affirms the right of every American citizen to bear arms. And as Americans, we will not give up a single right guaranteed under the Constitution. The history of unpunished violence against our people clearly indicates that we must be prepared to defend ourselves, or we will continue to be a defenseless people at the mercy of a ruthless and violent, racist mob.

AMY GOODMAN: And this is Malcolm X almost a before he was assassinated, at a speech given in Detroit April 12, 1964, known as “The Ballot or the Bullet.”

MALCOLM X: Just as it took nationalism to move—to remove colonialism from Asia and Africa, it’ll take black nationalism today to remove colonialism from the backs and the minds of 22 million Afro-Americans here in this country.

Looks like it might be the year of the ballot or the bullet. Why does it look like it might be the year of the ballot or the bullet? Because Negroes have listened to the trickery and the lies and the false promises of the white man now for too long. And they’re fed up. They’ve become disenchanted. They’ve become disillusioned. They’ve become dissatisfied, and all of this has built up frustrations in the black community that makes the black community throughout America today more explosive than all of the atomic bombs the Russians can ever invent.

AMY GOODMAN: Malcolm X. We now end today’s show with the late Ossie Davis, the actor and activist, delivering the eulogy for Malcolm X. This is from the Pacifica Radio Archive. It was at the Faith Temple Church of God in New York just a few days after Malcolm X was assassinated. He gave it February 27, 1965.

OSSIE DAVIS: My appreciation of Malcolm, in addition to all of the other things he meant as a leader, as a teacher, as a man, a philosopher, as a man who knew the facts of life, as an Africanist, as an economist, as a political scholar, as an agitator, the thing that struck me most about him was that Malcolm was a man. I mean man in a particular sense. Malcolm had created a new style for those of us who would be men to follow. Not only black men, but also white men. Malcolm left us the heritage of manhood, which in our country has long been going out of style.

And if you don’t believe it, if you’ll remember last February—last March, when 38 people sat by the telephone and refused to pick it up when a young lady was calling for help, and she called three times, and these 38 citizens, who represent us, let the lady die without picking up the phone to call the police. That is the state of our manhood in this country today. And those were not Negro people who did that. They were whites. We have ceased to care. We have ceased to be concerned. We have ceased to remember our humanity. We are things. We are cogs. We are close to being dehumanized in this great country of ours.

Malcolm came along and said, “Stop. Stop. You are men. Stop. You do care. Stop. There is life in you. Stop. There is still the possibility that manhood, that courage, that strength, that imagination, will make the difference.” It was he who rallied our flagging efforts, who taught us to stand up off of our knees—especially the black men, but also the whites—to stand up off of our knees, to address ourselves to the truth, even if we were killed for it. And it’s been a long time since that kind of courage and bravery was abroad in our land.

We’ve had men, men who were martyrs, men who were mighty, men who set us great and good examples. But they had one advantage that Malcolm did not have. They were men of education. They were men of college. They had had training. Malcolm came from the lowest depth. And therefore, in measuring the man, we have to measure the place from whence he came. All of us sitting here tonight, men and women, black and white, can stand a little taller because a man like Malcolm X walked on our Earth, lived in our midst, smiled his smile on the face of Harlem.

I am happy to have known him. And if there is a possibility of redemption for me, for you, for Harlem, for our country, Malcolm is the man who said that such a redemption was possible, and when he died, he was pointing the way to this redemption. We sat tonight. We were uplifted by the singing, by the dancing, by the presence of great leaders among us, and you must have noticed that our greatest leaders turned out to be women. Now, this—there is a reason why this is so. And it’s the same reason why a man would hesitate to keep a picture of Malcolm X on his wall. And that reason is that as black men we have been the most systematically emasculated people on the face of the Earth. And we have learned, unfortunately, to accept and live with our emasculation as if this is the definition of what we are. Malcolm said, “No, you are a man. I will make you see that you are a man.” He insisted on ripping the lies from our face, our middle-class smugness. He talked to all of us.

Get up off your knees. Come out of your hiding place. If your hiding place is gold, come out from behind it. If your hiding place is prestige, come out from behind it. If your hiding place is poverty, if you live in the slums, if you live in the gutters, stand up, look at the sun. You, too, are a man. And when Malcolm said it, when he looked at you, when he gave you the stuff of your own manhood, how could we resist or deny or do less than the little we did to honor him when he died and here tonight? Great things sometimes show up very small. The cloud no bigger than a man’s hand betokened the flood that destroyed the Earth. Many looking on the reception, what has happened since Malcolm has been dead, seeing the kind of reception that we have gotten and that we have not gotten, might make the mistake of thinking that we have measured the man, we have put him in his place, and therefore we can safely turn around and forget him forever. But that is not so. I say this to you, as I say to myself: If Malcolm and his message, so strong, so bright and so pure, was too good for those of us who have already reached manhood, there is a generation who is not yet spoiled, not yet degutted, not yet de-bold, not yet emasculated, who when they come into the light of this truth will rise up and redeem him and us and all the rest of the world. That is the meaning of Malcolm X.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Ossie Davis remembering Malcolm X. It’s the 50th anniversary of his assassination. He was killed February 21, 1965.

Media Options